Tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is a type of heart defect present at birth.[4] Symptoms at birth may vary from none to severe.[9] Later, there are typically episodes of bluish color to the skin known as cyanosis.[2] When affected babies cry or have a bowel movement, they may develop a "tet spell" where they turn very blue, have difficulty breathing, become limp, and occasionally lose consciousness.[2] Other symptoms may include a heart murmur, finger clubbing, and easy tiring upon breastfeeding.[2]

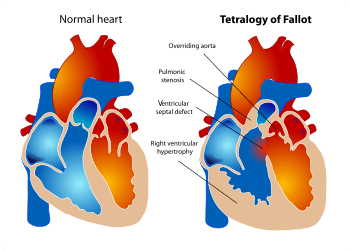

| Tetralogy of Fallot | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Fallot’s syndrome, Fallot’s tetrad, Steno-Fallot tetralogy[1] |

| |

| Diagram of a healthy heart and one with tetralogy of Fallot | |

| Specialty | Cardiac surgery, pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Episodes of bluish color to the skin, difficulty breathing, heart murmur, finger clubbing[2] |

| Complications | Irregular heart rate, pulmonary regurgitation[3] |

| Usual onset | From birth[4] |

| Causes | Unknown[5] |

| Risk factors | Alcohol, diabetes, >40, rubella during pregnancy[5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, echocardiogram[6] |

| Differential diagnosis | Transposition of the great arteries, Eisenmenger syndrome, Ebstein anomaly[7] |

| Treatment | Open heart surgery[8] |

| Frequency | 1 in 2,000 babies[4] |

The cause is typically not known.[5] Risk factors include a mother who uses alcohol, has diabetes, is over the age of 40, or gets rubella during pregnancy.[5][10] It may also be associated with Down syndrome.[5] Classically there are four defects:[4]

- pulmonary stenosis, narrowing of the exit from the right ventricle

- a ventricular septal defect, a hole between the two ventricles

- right ventricular hypertrophy, thickening of the right ventricular muscle

- an overriding aorta, which allows blood from both ventricles to enter the aorta

TOF is typically treated by open heart surgery in the first year of life.[8] Timing of surgery depends on the baby's symptoms and size.[8] The procedure involves increasing the size of the pulmonary valve and pulmonary arteries and repairing the ventricular septal defect.[8] In babies who are too small, a temporary surgery may be done with plans for a second surgery when the baby is bigger.[8] Most people who are affected live to be adults.[4] Long-term problems may include an irregular heart rate and pulmonary regurgitation.[3]

TOF occurs in about 1 in 2,000 newborns.[4] Males and females are affected equally.[4] It is the most common complex congenital heart defect accounting for about 10 percent of cases.[11][12] It was initially described in 1671 by Niels Stensen.[1][13] A further description was published in 1888 by the French physician Étienne-Louis Arthur Fallot, after whom it is named.[1][14] The first total surgical repair was carried out in 1954.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Tetralogy of Fallot results in low oxygenation of blood. This is due to a mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in the left ventricle via the ventricular septal defect (VSD) and preferential flow of the mixed blood from both ventricles through the aorta because of the obstruction to flow through the pulmonary valve. The latter is known as a right-to-left shunt.[15]

Infants with TOF -a cyanotic heart disease- have low blood oxygen saturation.[16] Blood oxygenation varies greatly from one patient to another depending on the severity of the anatomic defects.[9] Typical ranges vary from 60% to around 90%.[16] Depending on the degree of obstruction, symptoms vary from no cyanosis or mild cyanosis to profound cyanosis at birth.[9] If the baby is not cyanotic then it is sometimes referred to as a "pink tet".[17] Other symptoms include a heart murmur which may range from almost imperceptible to very loud, difficulty in feeding, failure to gain weight, retarded growth and physical development, labored breathing (dyspnea) on exertion, clubbing of the fingers and toes, and polycythemia.[2] The baby may turn blue with breast feeding or crying.[2]

Tet spells

Infants and children with unrepaired tetralogy of Fallot may develop "tet spells".[15] These are acute hypoxia spells, characterized by shortness of breath, cyanosis, agitation, and loss of consciousness.[18] This may be initiated by any event -such as anxiety, pain, dehydration, or fever-[19] leading to decreased oxygen saturation or that causes decreased systemic vascular resistance, which in turn leads to increased shunting through the ventricular septal defect.[15]

Clinically, tet spells are characterized by a sudden, marked increase in cyanosis followed by syncope.[18]

Older children will often squat instinctively during a tet spell.[15] This increases systemic vascular resistance and allows for a temporary reversal of the shunt. It increases pressure on the left side of the heart, decreasing the right to left shunt thus decreasing the amount of deoxygenated blood entering the systemic circulation.[20][21]

Cause

Its cause is thought to be due to environmental or genetic factors or a combination. It is associated with chromosome 22 deletions and DiGeorge syndrome.[22]

Specific genetic associations include: JAG1,[23] NKX2-5,[24] ZFPM2,[25] VEGF,[26] NOTCH1, TBX1, and FLT4.[27]

Embryology studies show that it is a result of anterior malalignment of the aorticopulmonary septum, resulting in the clinical combination of a VSD, pulmonary stenosis, and an overriding aorta.[18] Right ventricular hypertrophy develops progressively from resistance to blood flow through the right ventricular outflow tract.[9]

Pathophysiology

The main anatomic defect in TOF is the anterior deviation of the pulmonary outflow septum.[9] This defect results in narrowing of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), override of the aorta, and a ventricular septal defect (VSD).[28]

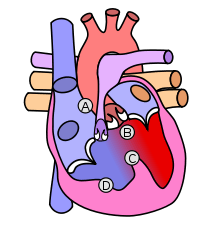

Four malformations

"Tetralogy" denotes four parts, here implying the syndrome's four anatomic defects.[2] This is not to be confused with the similarly named teratology, a field of medicine concerned with abnormal development and congenital malformations (including tetralogy of Fallot). Below are the four heart malformations that present together in tetralogy of Fallot:

| Condition | Description |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary Infundibular Stenosis | A narrowing of the right ventricular outflow tract. It can occur at the pulmonary valve (valvular stenosis) or just below the pulmonary valve (infundibular stenosis). Infundibular pulmonic stenosis is mostly caused by overgrowth of the heart muscle wall (hypertrophy of the septoparietal trabeculae),[29] however the events leading to the formation of the overriding aorta are also believed to be a cause. The pulmonic stenosis is the major cause of the malformations, with the other associated malformations acting as compensatory mechanisms to the pulmonic stenosis.[30] The degree of stenosis varies between individuals with TOF, and is the primary determinant of symptoms and severity. This malformation is infrequently described as sub-pulmonary stenosis or subpulmonary obstruction.[31] |

| Overriding aorta | An aortic valve with biventricular connection, that is, it is situated above the ventricular septal defect and connected to both the right and the left ventricle. The degree to which the aorta is attached to the right ventricle is referred to as its degree of "override." The aortic root can be displaced toward the front (anteriorly) or directly above the septal defect, but it is always abnormally located to the right of the root of the pulmonary artery. The degree of override is extremely variable, with 5-95% of the valve being connected to the right ventricle.[29] |

| Ventricular septal defect (VSD) | A hole between the two bottom chambers (ventricles) of the heart. The defect is centered around the most superior aspect of the ventricular septum (the outlet septum), and in the majority of cases is single and large. In some cases thickening of the septum (septal hypertrophy) can narrow the margins of the defect.[29] |

| Right ventricular hypertrophy | The right ventricle is more muscular than normal, causing a characteristic boot-shaped (coeur-en-sabot) appearance as seen by chest X-ray. Due to the misarrangement of the external ventricular septum, the right ventricular wall increases in size to deal with the increased obstruction to the right outflow tract. This feature is now generally agreed to be a secondary anomaly, as the level of hypertrophy tends to increase with age.[32] |

There is anatomic variation between the hearts of individuals with tetralogy of Fallot.[9] Primarily, the degree of right ventricular outflow tract obstruction varies between patients and generally determines clinical symptoms and disease progression.[9]

Presumably, this arises from an unequal growth of the aorticopulmonary septum (aka pulmonary outflow septum).[33] The aorta is too large, thus "overriding," and this "steals" from the pulmonary artery, which is therefore stenosed. This then prevents ventricular wall closure, therefore VSD, and this increases the pressures on the right side, and so the R ventricle becomes bigger to handle the work.[33]

Additional anomalies

In addition, tetralogy of Fallot may present with other anatomical anomalies, including:[34][35]

- stenosis of the left pulmonary artery, in 40%

- a bicuspid pulmonary valve, in 60%

- right-sided aortic arch, in 25%

- coronary artery anomalies, in 10%

- a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect, in which case the syndrome is sometimes called a pentalogy of Fallot[36]

- an atrioventricular septal defect

- partially or totally anomalous pulmonary venous return

Tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia (pseudotruncus arteriosus) is a severe variant[37] in which there is complete obstruction (atresia) of the right ventricular outflow tract, causing an absence of the pulmonary trunk during embryonic development.[38] In these individuals, blood shunts completely from the right ventricle to the left where it is pumped only through the aorta. The lungs are perfused via extensive collaterals from the systemic arteries, and sometimes also via the ductus arteriosus.[38]

Diagnosis

Congenital heart defects are now diagnosed with echocardiography, which is quick, involves no radiation, is very specific, and can be done prenatally.[39]

Echocardiography establishes the presence of TOF by demonstrating a VSD, RVH, and aortic override. Many patients are diagnosed prenatally. Color Doppler (type of echocardiography) measures the degree of pulmonary stenosis. Additionally, close monitoring of the ductus arteriosus is done in the neonatal period to ensure that there is adequate blood flow through the pulmonary valve.[40] [41]

In certain cases, coronary artery anatomy cannot be clearly viewed using echocardiogram. In this case, cardiac catheterization can be done.[42]

Form a genetics perspective, it is important to screen for DiGeorge in all babies with TOF.[42]

Before more sophisticated techniques became available, chest x-ray was the definitive method of diagnosis. The abnormal "coeur-en-sabot" (boot-like) appearance of a heart with tetralogy of Fallot is classically visible via chest x-ray, although most infants with tetralogy may not show this finding.[43] The boot like shape is due to the right ventricular hypertrophy present in TOF. Lung fields are often dark (absence of interstitial lung markings) due to decreased pulmonary blood flow.[41]

Electrocardiography shows right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), along with right axis deviation.[40] RVH is noted on EKG as tall R-waves in lead V1 and deep S-waves in lead V5-V6.[44]

Treatment

Tet spells

Tet spells may be treated with beta-blockers such as propranolol, but acute episodes require rapid intervention with morphine or intranasal fentanyl[45] to reduce ventilatory drive, a vasopressor such as phenylephrine, or norepinephrine to increase systemic vascular resistance, and IV fluids for volume expansion.[46]

Oxygen (100%) may be effective in treating spells because it is a potent pulmonary vasodilator and systemic vasoconstrictor. This allows more blood flow to the lungs by decreasing shunting of deoxygenated blood from the right to left ventricle through the VSD. There are also simple procedures such as squatting and the knee chest position which increase systemic vascular resistance and decrease right-to-left shunting of deoxygenated blood into the systemic circulation.[46][47]

If the spells are refractory to the above treatments, people are usually intubated and sedated. The treatment of last resort for tet spells is extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) along with consideration of Blalock Taussig shunt (BT shunt).[46]

Total surgical repair

Total surgical repair of TOF is a curative surgery. Different techniques can be used in performing TOF repair. However, a transatrial, transpulmonary artery approach is used for most cases.[48] The repair consists of two main steps: closure of the VSD with a patch and reconstruction of the right ventricular outflow tract.[49]

This open-heart surgery is designed to relieve the right ventricular outflow tract stenosis by careful resection of muscle and to repair the VSD.[50] Additional reparative or reconstructive surgery may be done on patients as required by their particular cardiac anatomy.[51][52]

Timing of surgery in asymptomatic patients is usually between the ages of 2 months to one year.[53] However, in symptomatic patients showing worsening blood oxygen levels, severe tet-spells (cyanotic spells), or dependence on prostaglandins from early neonatal period (to keep the ductus arteriosus open) need to be planned fairly urgently.[53]

Potential surgical repair complications include residual ventricular septal defect, residual outflow tract obstruction, complete atrioventricular block, arrhythmias, aneurysm of right ventricular outflow patch, and pulmonary valve insufficiency.[54] Long term complications most commonly include pulmonary valve regurgitation, and arrhythmias.[55]

Total repair of tetralogy of Fallot initially carried a high mortality risk, but this risk has gone down steadily over the years. Surgery is now often carried out in infants one year of age or younger with less than 5% perioperative mortality[56]. Post surgery, most patients enjoy an active life free of symptoms.[56] Currently, long term survival is close to 90%.[57] Today the adult TOF population continues to grow and is one of the most common congenital heart defect seen in adult outpatient clinics.[58]

Palliative surgery

Initially surgery involved forming a side to end anastomosis between the subclavian artery and the pulmonary artery -i.e a systemic to pulmonary arterial shunt.[49] This redirected a large portion of the partially oxygenated blood leaving the heart for the body into the lungs, increasing flow through the pulmonary circuit, and relieving symptoms. The first Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt surgery was performed on 15-month-old Eileen Saxon on November 29, 1944 with dramatic results.[59]

The Potts shunt[60] and the Waterston-Cooley shunt[61][62] are other shunt procedures which were developed for the same purpose. These are no longer used.

Currently, palliative surgery is not normally performed on infants with TOF except for extreme cases.[63] For example, in symptomatic infants, a two-stage repair (initial systemic to arterial shunt placement followed by total surgical repair) may be done.[64] Potential complications include inadequate pulmonary blood flow, pulmonary artery distortion, inadequate growth of the pulmonary arteries, and acquired pulmonary atresia.[54]

Prognosis

Untreated, tetralogy of Fallot rapidly results in progressive right ventricular hypertrophy due to the increased resistance caused by narrowing of the pulmonary trunk.[33] This progresses to heart failure which begins in the right ventricle and often leads to left heart failure and dilated cardiomyopathy. Mortality rate depends on the severity of the tetralogy of Fallot. If left untreated, TOF carries a 35% mortality rate in the first year of life, and a 50% mortality rate in the first three years of life.[65] Patients with untreated TOF rarely progress to adulthood.[55]

Patients who have undergone total surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot have improved hemodynamics and often have good to excellent cardiac function after the operation with some to no exercise intolerance (New York Heart Association Class I-II).[66] Long-term outcome is usually excellent for most patients, however residual post surgical defects -such as pulmonary regurgitation, pulmonary artery stenosis, residual VSD, right ventricular dysfunction, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and sudden death- may affect life expectancy and increase the need for reoperation.[56]

Within 30 years after correction, 50% of patients will require reoperation.[55] The most common cause of reoperation is a leaky pulmonary valve (pulmonary valve insufficiency).[55] This is usually corrected with a procedure called pulmonary valve replacement. [67]

Epidemiology

Tetralogy of Fallot occurs approximately 400 times per million live births[68]. It accounts for 7 to 10% of all congenital heart abnormalities, making it the most common cyanotic heart defect.[58] Males and females are affected equally.[4] Genetically it is most commonly associated with Down's syndrome and DiGeorge syndrome.[5][22]

History

Tetralogy of Fallot was initially described in 1671 by Niels Stensen.[1][13] A further description was published in 1888 by the French physician Étienne-Louis Arthur Fallot, after whom it is named.[1][14] In 1924, Maude Abbott coined the term "tetralogy of Fallot".[69]

The first surgical repair was carried out in 1944 at Johns Hopkins.[70] The procedure was conducted by surgeon Alfred Blalock and cardiologist Helen B. Taussig, with Vivien Thomas also providing substantial contributions and listed as an assistant.[3] This first surgery was depicted in the film Something the Lord Made.[59] It was actually Helen Taussig who convinced Alfred Blalock that the shunt was going to work. 15-month-old Eileen Saxon was the first person to receive a Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt.[59] Furthermore, the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig procedure, initially the only surgical treatment available for tetralogy of Fallot, was palliative but not curative. The first total repair of tetralogy of Fallot was done by a team led by C. Walton Lillehei at the University of Minnesota in 1954 on an 11-year-old boy.[71] Total repair on infants has had success from 1981, with research indicating that it has a comparatively low mortality rate.[66] Today the adult TOF population continues to grow and is one of the most common congenital heart defect seen in adult outpatient clinics.[58]

Notable cases

- Shaun White,[72] American professional snowboarder and skateboarder

- Beau Casson,[73] Australian cricketer

- Dennis McEldowney,[74] New Zealand author and publisher

- Max Page, Volkswagen's "Little Darth Vader" from the 2011 Super Bowl commercial[75]

- Billy Kimmel, the son of talk show host Jimmy Kimmel; Billy's diagnosis led Kimmel to discuss access to health care on his show Jimmy Kimmel Live![76]

See also

References

- "Fallot's tetralogy". Whonamedit?. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Tetralogy of Fallot?". NHLBI. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- Warnes, Carole A. (July 2005). "The Adult With Congenital Heart Disease". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 46 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.083. PMID 15992627.

- "What Is Tetralogy of Fallot?". NHLBI. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "What Causes Tetralogy of Fallot?". NHLBI. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "How Is Tetralogy of Fallot Diagnosed?". NHLBI. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Prasad, Rajnish; Kahan, Scott; Mohan, Pankaj (2007). In a Page: Cardiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781764964.

- "How Is Tetralogy of Fallot Treated?". NHLBI. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- Hay, William W.; Levin, Myron J.; Deterding, Robin R.; Abzug, Mark J. (2016-05-02). Current diagnosis & treatment : pediatrics (Twenty-third ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9780071848541. OCLC 951067614.

- Pregnancy and congenital heart disease. Roos-Hesselink, Jolien W., Johnson, Mark R. Cham: Springer. 2017. p. 62. ISBN 9783319389134. OCLC 969644876.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Yuh, David D. (2014). Johns Hopkins textbook of cardiothoracic surgery (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. ISBN 9780071663502. OCLC 828334087.

- "Types of Congenital Heart Defects". NHLBI. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- Van Praagh, R (2009). "The first Stella van Praagh memorial lecture: the history and anatomy of tetralogy of Fallot". Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Annual. 12: 19–38. doi:10.1053/j.pcsu.2009.01.004. PMID 19349011.

- Fallot, Arthur (1888). Contribution à l'anatomie pathologique de la maladie bleue (cyanose cardiaque), par le Dr. A. Fallot, ... (in French). Marseille: Impr. de Barlatier-Feissat. pp. 77–93. OCLC 457786038.

- Heart diseases in children : a pediatrician's guide. Abdulla, Ra-id. New York: Springer. 2011. pp. 169–70. ISBN 9781441979940. OCLC 719361786.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Heart diseases in children : a pediatrician's guide. Abdulla, Ra-id. New York: Springer. 2011. pp. 169–70. ISBN 9781441979940. OCLC 719361786.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Tetralogy of Fallot: Overview - eMedicine". Archived from the original on 2008-12-23. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. p. 200. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. p. 18. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Murakami T (2002). "Squatting: the hemodynamic change is induced by enhanced aortic wave reflection". Am. J. Hypertens. 15 (11): 986–8. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(02)03085-6. PMID 12441219.

- Guntheroth WG, Mortan BC, Mullins GL, Baum D. Am Venous return with knee-chest position and squatting in tetralogy of Fallot. Heart J. 1968 Mar;75(3):313-8.

- Francois., Lacour-Gayet (2016-03-29). Surgery of conotruncal anomalies. Bove, Edward L.,, Hras̆ka, Viktor., Morell, Victor O.,, Spray, Thomas L. Cham. p. 62. ISBN 9783319230573. OCLC 945874817.

- Eldadah ZA, Hamosh A, Biery NJ, et al. (January 2001). "Familial Tetralogy of Fallot caused by mutation in the jagged1 gene". Hum. Mol. Genet. 10 (2): 163–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.2.163. PMID 11152664.

- Goldmuntz E, Geiger E, Benson DW (November 2001). "NKX2.5 mutations in patients with tetralogy of Fallot". Circulation. 104 (21): 2565–8. doi:10.1161/hc4601.098427. PMID 11714651.

- Pizzuti A, Sarkozy A, Newton AL, et al. (November 2003). "Mutations of ZFPM2/FOG2 gene in sporadic cases of tetralogy of Fallot". Hum. Mutat. 22 (5): 372–7. doi:10.1002/humu.10261. PMID 14517948.

- Lambrechts D, Devriendt K, Driscoll DA, et al. (June 2005). "Low expression VEGF haplotype increases the risk for tetralogy of Fallot: a family based association study". J. Med. Genet. 42 (6): 519–22. doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.026443. PMC 1736071. PMID 15937089.

- Page DJ, Miossec MJ, Williams SG, Monaghan RM, Fotiou E, Cordell H, Sutcliffe L, Topf A, Bourgey M, Bourque G, Eveleigh R, Dunwoodie SL, Winlaw DS, Bhattacharya S, Breckpot J, Devriendt K, Gewillig M, Brook JD, Setchfield KJ, Bu'Lock F, o'sullivan JJ, Stuart G, Bezzina CR, Mulder BJ, Postma AV, Bentham JR, Baron M, Bhaskar SS, Black GC, Newman WG, Hentges KE, Lathrop GM, Santibanez Koref M, Keavney B (2018) Whole exome sequencing reveals the major genetic contributors to non-syndromic tetralogy of Fallot. Circ Res

- Jameson, J. Larry; Kasper, Dennis L.; Fauci, Anthony S.; Hauser, Stephen L.; Longo, Dan L.; Loscalzo, Joseph (2018-02-06). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (Twentieth ed.). New York. ISBN 9781259644047. OCLC 990065894.

- Gatzoulis MA, Webb GD, Daubeney PE. (2005) Diagnosis and Management of Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia. ISBN 0-443-07103-9.

- Bartelings M, Gittenberger-de Groot A (1991). "Morphogenetic considerations on congenital malformations of the outflow tract. Part 1: Common arterial trunk and tetralogy of Fallot". Int. J. Cardiol. 32 (2): 213–30. doi:10.1016/0167-5273(91)90329-N. PMID 1917172.

- Anderson RH, Weinberg. The clinical anatomy of tetralogy of Fallot. Cardiol Young. 2005 15;38-47. PMID 15934690.

- Anderson RH, Tynan M. Tetralogy of Fallot – a centennial review. Int J Cardiol. 1988 21; 219-232. PMID 3068155.

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. p. 199. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Francois., Lacour-Gayet (2016-03-29). Surgery of conotruncal anomalies. Bove, Edward L., Hras̆ka, Viktor., Morell, Victor O.,, Spray, Thomas L. Cham. pp. 66–8. ISBN 9783319230573. OCLC 945874817.

- Bove, Edward L.; Crowley, Dennis C.; Urcelay, Gonzalo; Mosca, Ralph S.; Hennein, Hani A. (1995-02-01). "Intermediate results after complete repair of tetralogy of Fallot in neonates". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 109 (2): 332–344. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70395-0. ISSN 0022-5223. PMID 7531798.

- Cheng TO (1995). "Pentalogy of Cantrell vs pentalogy of Fallot". Tex Heart Inst J. 22 (1): 111–2. PMC 325224. PMID 7787464.

- Farouk A, Zahka K, Siwik E, et al. (December 2008). "Individualized approach to the surgical treatment of tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia". Cardiol Young. 19 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1017/S1047951108003430. PMID 19079949.

- Francois., Lacour-Gayet (2016-03-29). Surgery of conotruncal anomalies. Bove, Edward L.,, Hras̆ka, Viktor., Morell, Victor O.,, Spray, Thomas L. Cham. pp. 67–8. ISBN 9783319230573. OCLC 945874817.

- "Congenital Heart Defects | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- Francois., Lacour-Gayet (2016-03-29). Surgery of conotruncal anomalies. Bove, Edward L.,, Hras̆ka, Viktor., Morell, Victor O.,, Spray, Thomas L. Cham. p. 113. ISBN 9783319230573. OCLC 945874817.

- Heart diseases in children : a pediatrician's guide. Abdulla, Ra-id. New York: Springer. 2011. pp. 171–72. ISBN 9781441979940. OCLC 719361786.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. pp. 37, 201. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Weerakkody, Yuranga. "Tetralogy of Fallot - Radiology Reference Article - Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-20.

- "Right Ventricular Hypertrophy (RVH) • LITFL • ECG Library Diagnosis". Life in the Fast Lane. 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2019-01-21.

- Tsze DS, Vitberg YM, Berezow J, Starc TJ, Dayan PS (2014). "Treatment of tetralogy of fallot hypoxic spell with intranasal fentanyl". Pediatrics. 134 (1): e266–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3183. PMID 24936003.

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. pp. 18, 201. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Murakami T (2002). "Squatting: the hemodynamic change is induced by enhanced aortic wave reflection". Am. J. Hypertens. 15 (11): 986–8. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(02)03085-6. PMID 12441219.

- Mavroudis, Constantine; Backer, Carl Lewis (2015-10-24). Atlas of pediatric cardiac surgery. Mavroudis, Constantine,, Backer, Carl Lewis,, Idriss, Rachid F. London. p. 153. ISBN 9781447153191. OCLC 926915143.

- F., Corno, Antonio (2009). Congenital heart defects : decision making for cardiac surgery. Volume 3, CT-scan and MRI. Darmstadt: Steinkopff. p. 57. ISBN 9783798517196. OCLC 433550801.

- Mavroudis, Constantine; Backer, Carl Lewis (2015-10-24). Atlas of pediatric cardiac surgery. Mavroudis, Constantine,, Backer, Carl Lewis,, Idriss, Rachid F. London. p. 154. ISBN 9781447153191. OCLC 926915143.

- Mavroudis, Constantine; Backer, Carl Lewis (2015-10-24). Atlas of pediatric cardiac surgery. Mavroudis, Constantine,, Backer, Carl Lewis,, Idriss, Rachid F. London. pp. 153–63. ISBN 9781447153191. OCLC 926915143.

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. pp. 202–03. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. pp. 201–2. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- F., Corno, Antonio (2009). Congenital heart defects : decision making for cardiac surgery. Volume 3, CT-scan and MRI. Darmstadt: Steinkopff. p. 59. ISBN 9783798517196. OCLC 433550801.

- The right ventricle in adults with tetralogy of fallot. Chessa, Massimo., Giamberti, Alessandro. Milan: Springer. 2012. p. 155. ISBN 9788847023581. OCLC 813213115.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. p. 205. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The right ventricle in adults with tetralogy of fallot. Chessa, Massimo., Giamberti, Alessandro. Milan: Springer. 2012. p. 167. ISBN 9788847023581. OCLC 813213115.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Pregnancy and congenital heart disease. Roos-Hesselink, Jolien W., Johnson, Mark R. Cham: Springer. 2017. pp. 100–01. ISBN 9783319389134. OCLC 969644876.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "First Operations; Blalock - Taussig Shunt". Archived from the original on 2007-11-30. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- Boshoff D, Budts W, Daenen W, Gewillig M (January 2005). "Transcatheter closure of a Potts' shunt with subsequent surgical repair of tetralogy of fallot". Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 64 (1): 121–3. doi:10.1002/ccd.20247. PMID 15619282.

- Daehnert I, Wiener M, Kostelka M (May 2005). "Covered stent treatment of right pulmonary artery stenosis and Waterston shunt". Ann. Thorac. Surg. 79 (5): 1754–5. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.11.059. PMID 15854971.

- "Systemic to Pulmonary Artery Shunting for Palliation: - eMedicine". Archived from the original on 2008-12-29. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- Heart diseases in children : a pediatrician's guide. Abdulla, Ra-id. New York: Springer. 2011. p. 173. ISBN 9781441979940. OCLC 719361786.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Critical care of children with heart disease : basic medical and surgical concepts. Munoz, Ricardo (Ricardo A.). London: Springer-Verlag. 2010. p. 217. ISBN 9781848822627. OCLC 663096154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The right ventricle in adults with tetralogy of fallot. Chessa, Massimo., Giamberti, Alessandro. Milan: Springer. 2012. p. 155. ISBN 9788847023581. OCLC 813213115.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Total correction of tetralogy of fallot in the first year of life: late results". Archived from the original on 2012-07-07..

- Francois., Lacour-Gayet (2016-03-29). Surgery of conotruncal anomalies. Bove, Edward L.,, Hras̆ka, Viktor., Morell, Victor O.,, Spray, Thomas L. Cham. p. 136. ISBN 9783319230573. OCLC 945874817.

- Child JS (July 2004). "Fallot's tetralogy and pregnancy: prognostication and prophesy". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 44 (1): 181–3. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.009. PMID 15234430.

- Abbott ME, Dawson WT (1924). "The clinical classification of congenital cardiac disease, with remarks upon its pathological anatomy, diagnosis and treatment". Int Clin. 4: 156–88.

- Sun, Baltimore. "Vivien Thomas helped develop the 'blue baby' operation at Johns Hopkins". Baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Lillehei CW; Cohen, M; Warden, HE; Read, RC; Aust, JB; Dewall, RA; Varco, RL (1955). "Direct Vision Intracardiac Surgical Correction of the Tetralogy of Fallot, Pentalogy of Fallot, and Pulmonary Atresia Defects Report of First Ten Cases". Ann. Surg. 142 (3): 418–442. doi:10.1097/00000658-195509000-00010. PMC 1465089. PMID 13249340.

- "SI.com - SI Adventure - Double Ripper - Wednesday July 02, 2003 05:14 PM". CNN. Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- "New twist in Casson's amazing journey - Cricket - Sport - smh.com.au". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2008-06-06. Archived from the original on 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- "McEldowney, Dennis". Archived from the original on 2008-10-16. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- "'Little Darth Vader' reveals face behind the Force". 7 February 2011.

- "Aide to All the Times Jimmy Kimmel Has Gotten Political". Time. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tetralogy of Fallot. |