2016–19 Yemen cholera outbreak

An outbreak of cholera began in Yemen in October 2016,[3] and is ongoing as of April 2019.[4] In February and March 2017, the outbreak seemed to decline during a wave of cold weather, but the number of cholera cases resurged in April 2017.[5] As of October 2018, there have been more than 1.2 million cases reported, and more than 2,500 people—58% children—have died in the Yemen cholera outbreak, which the United Nations has deemed the worst humanitarian crisis in the world.[6]

.svg.png) | |

| Disease | Cholera |

|---|---|

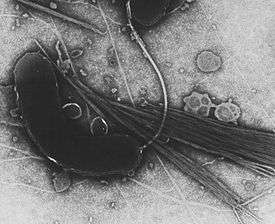

| Bacteria strain | Vibrio cholerae |

| Dates | October 2016 – present (3 years and 2 months) |

| Origin | Yemeni Civil War Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen Saudi Blockade of Yemen Famine in Yemen (2016–present) |

| Deaths | 3,785 [1] |

| Suspected cases‡ | 2,118,387 through September 2019 [2] |

| ‡ Suspected cases have not been confirmed as being due to this strain by laboratory tests, although some other strains may have been ruled out. | |

Vulnerable to water-borne diseases before the conflict, 16 months went by before a program of oral vaccines was started.[6] The cholera outbreak was worsened as a result of the ongoing civil war and the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Houthi movement that began in March 2015.[6][5] Airstrikes damaged hospital infrastructure,[7] and water supply and sanitation in Yemen were affected by the ongoing conflict.[5][8] The government of Yemen stopped funding public health in 2016;[9] sanitation workers were not paid by the government, causing garbage to accumulate,[7] and healthcare workers either fled the country or were not paid.[5]

The UNICEF and World Health Organization (WHO) executive directors stated: "This deadly cholera outbreak is the direct consequence of two years of heavy conflict. Collapsing health, water and sanitation systems have cut off 14.5 million people from regular access to clean water and sanitation, increasing the ability of the disease to spread. Rising rates of malnutrition have weakened children's health and made them more vulnerable to disease. An estimated 30,000 dedicated local health workers who play the largest role in ending this outbreak have not been paid their salaries for nearly ten months."[10]

Background

As of 2017, Yemen had a population of about 25 million and was geographically divided into 22 governorates.[5]

The Yemeni Civil War is an ongoing conflict that began in 2015 between two factions: the internationally recognized Yemeni government, led by Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, and the Houthi armed movement, along with their supporters and allies. Both claim to constitute the official government of Yemen.[11] Houthi forces controlling the capital Sanaʽa, and allied with forces loyal to the former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, have clashed with forces loyal to the government of Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, based in Aden.[12] A Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen was launched in 2015, with Saudi Arabia leading a coalition of nine countries from the Middle East and Africa, in response to calls from president Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi for military support.[13][14]

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae.[15][16] It is spread mostly by unsafe water and unsafe food that has been contaminated with human feces containing the bacteria.[17] Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe.[16] The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days.[17] Diarrhea can be so severe that it leads within hours to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.[17] The primary treatment is oral rehydration therapy—the replacement of fluids with slightly sweet and salty solutions.[17] In severe cases, intravenous fluids may be required, and antibiotics may be beneficial.[17]

Prevention methods against cholera include improved sanitation and access to clean water.[18] Cholera vaccines that are given by mouth provide reasonable protection for about six months.[17] Two oral killed vaccines are available: Dukoral and Shanchol.[3] Total cost, including delivery costs, of oral cholera vaccination is under US$10 per person.[6]

Outbreak

Following "on the heels of civil conflict between Houthi rebels and the internationally recognized Yemeni regime",[5] the Yemen cholera outbreak began in early October 2016,[6][19] and by January 2017, the WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (WHO EMRO) considered the outbreak to be unusual in its rapid and wide geographical spread.[20] The serotype of vibrio cholerae O1 involved is Ougawa.[5][21]

The earliest cases were predominantly in the capital, Sana'a,[5] with some occurring in Aden.[22] By the end of October, cases had been reported in the governorates of Al-Bayda, Aden, Al-Hudaydah, Hajjah, Ibb, Lahij and Taiz and,[23] by late November, also in Al-Dhale'a and Amran.[24] By mid-December, 135 districts of 15 governorates had reported suspected cases, but nearly two-thirds were confined to Aden, Al-Bayda, Al-Hudaydah and Taiz.[5][25] By mid-January 2017, 80% of cases were located in 28 districts of Al-Dhale'a, Al-Hudaydah, Hajjah, Lahij and Taiz.[20] A total of 268 districts from 20 governorates had reported cases by 21 June 2017;[26] over half are from the governorates of Amanat Al Asimah (the capital Sana'a), Al-Hudaydah, Amran and Hajjah, which are all located in the west of the country.[21] In particular, 77.7% of cholera cases (339,061 of 436,625) and 80.7% of deaths from cholera (1,545 of 1,915) occurred in Houthi-controlled governorates, compared to 15.4% of cases and 10.4% of deaths in government-controlled governorates.[27]

Morbidity and mortality

Yemen authorities announced the cholera outbreak on 6 October 2016.[3] By the end of that year, there were 96 deaths.[3]

Following the October 2016 outbreak, the rate of spread in most areas had declined by the end of February 2017,[28] and by mid-March 2017, the outbreak was in decline after a wave of cold weather.[5] A total of 25,827 suspected cases, including 129 deaths, had been reported by 26 April 2017.[19]

The number of cholera cases resurged in a second wave that began on 27 April 2017.[19] According to Qadri, Islam and Clemens, writing in The New England Journal of Medicine, the dramatic April 2017 resurgence was "coincident with heavy rains that may have contaminated drinking water sources, and was amplified by war-related destruction of municipal water and sewage systems".[5]

During May 2017, 74,311 suspected cases, including 605 deaths, were reported.[19] By June, UNICEF and WHO estimated that 5,000 new cases per day were occurring, and that the total number of cases in the country since the outbreak began in October had exceeded 200,000, with 1,300 deaths.[10][29][30] The two agencies stated that it was then "the worst cholera outbreak in the world".[10]

By 4 July 2017, there were 269,608 cases and the death toll was at 1,614 with a case fatality rate of 0.6%.[31] On 14 August 2017 the WHO updated the number of suspected cholera cases to 500,000.[32] Oxfam said in 2017 the outbreak would become the largest epidemic since record-keeping began, overtaking the 754,373 cases of cholera recorded after the 2010 Haiti earthquake.[33] In six months, more people were ill with cholera in Yemen than in seven years after the earthquake in Haiti, and the situation in Yemen was made worse by hunger and malnutrition.[9]

On 22 December 2017, the World Health Organization reported the number of suspected cholera cases in Yemen had surpassed one million.[34]

As of October 2018, there have been more than 1.2 million cases reported, and more than 2,500 people—58% children—have died in the Yemen cholera outbreak, which is the worst epidemic in recorded history and was, according to the United Nations (UN), the worst humanitarian crisis in the world.[6] The case fatality rate for the outbreak was 0.21% as of 2018,[6] having declined from a high of 1% when the outbreak began.[9]

Causes and challenges

UNICEF and WHO attributed the outbreak to malnutrition, collapsing sanitation and clean water systems due to the country's ongoing conflict, and the approximately 30,000 local health care workers who had not been paid for almost a year.[10] A vaccination program was not started until more than a million people were ill, and the Yemen conflict worsened the cholera epidemic.[6]

Pre-civil war conditions

Even before civil war affected Yemen, it was "beset by circumstances that made it ripe for cholera". Extremely poor, Yemen suffers frequent droughts and severe water problems, and only about half of the population had access to good water and sanitation.[5]

Children under five showed a high prevalence of malnutrition, making them further susceptible to disease;[6] Yemen had "one of the highest rates of childhood malnutrition worldwide".[3] The health care system in Yemen before the conflict was weak and lacking infrastructure.[3] Before the war, 70–80% of children were vaccinated, but the vaccination rate had dropped by the end of 2015.[3]

Ongoing conflict

Because of the ongoing conflict in Yemen, and resulting displacement of people who do not have adequate food, waster, housing or sanitation, pre-existing conditions are exacerbated. Shortages have been made worse by naval and air blockades. Bombing has damaged water and sanitation infrastructure.[5] Airstrikes have destroyed facilities in the country for health care;[5] "half of the nation's hospitals have been either destroyed by Saudi airstrikes, occupied by rebel forces, or shut down because there are no medical personnel to staff them".[7]

Doctors Without Borders reported that a Saudi Arabian coalition airstrike hit a new Médecins Sans Frontières cholera treatment center in Abs, in northwestern Yemen. Doctors Without Borders reported that they had provided GPS coordinates to Saudi Arabia on twelve separate occasions, and had received nine written responses confirming receipt of those coordinates [35]

Grant Pritchard, Save the Children's interim country director for Yemen, stated in April 2017, "With the right medicines, these [diseases] are all completely treatable – but the Saudi Arabia-led coalition is stopping them from getting in."[36]

Health services and infrastructure collapse

As of 2016, the government ended funding for public health, leaving many employees without salary.[9] The impacts of the outbreak were exacerbated by the collapse of the Yemeni health services, where many health workers remained unpaid for months.[37] A months-long strike of sanitation workers over unpaid wages contributed to the accumulation of garbage[5][7] that entered the water supply.[9]

Qadri, Islam and Clemens write that the dramatic April 2017 resurgence coincided with heavy rains, and "was amplified by war-related destruction of municipal water and sewage systems".[5] An International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) worker in Yemen noted that April's cholera resurgence began ten days after Sana'a's sewer system stopped working.[37]

Raslan et al write in Frontiers in Public Health:

A failing sewage system, continued conflict and inadequate health care facilities are only a few of the reasons contributing to this problem. Malnutrition, which is a significant consequence of the Yemen War, has further contributed to this outbreak.[3]

Lack of vaccination

The International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision, which maintains vaccine stockpiles for cholera, announced a plan in June 2017 to send one million doses of oral cholera vaccine (OCV) to Yemen, but that plan stalled.[3][38] Controversy surrounded whether vaccination was the best strategy, whether it was too late to start a vaccination campaign, whether there was enough stockpiled vaccine to meet worldwide needs, whether all of the reported cases of cholera in Yemen were actually cholera or just people with diarrhea showing up at cholera treatment centers, and the effectiveness of the vaccine.[38] The request for vaccine was retracted.[6][5]

In May 2018, the first oral cholera vaccine campaign in Yemen was launched.[39] The WHO and UNICEF delivered oral vaccines to 540,000 individuals in August 2018.[6]

Federspiel and Ali write in BMC Public Health:

OCVs were not delivered until nearly 3.5 years into this humanitarian emergency, which has most likely been due to ongoing conflict, logistical circumstances, the scale of the epidemic, impairment of the humanitarian response by the parts to the conflict and some degree of negligence from donors, politicians and other decision makers. Whatever the reasons, OCVs were not distributed until nearly 16 months into the cholera outbreak by which time more than a million cases had accumulated. Neither were they in the two years of WaSH infrastructure breakdown that preceded the outbreak. This should serve as a historic example of the failure to control the spread of cholera given the tools that are available. Today, "cholera outbreaks are entirely containable" (The Lancet editorial, 2017).[6]

Humanitarian activity

Through 2018, several humanitarian healthcare organizations had reported activity to contain the cholera outbreak. The International Committee of the Red Cross says it supported 17 treatment centers with supplies including IV fluids, oral rehydration therapy supplies, antibiotics, chlorine tablets, in addition to sending engineers to help restore water distribution in Yemen.[6] The International Rescue Committee (IRC) supplied seven hospitals with medicine and supplies, deployed health teams and trained volunteers, delivered health and nutrition services, and facilitated referrals of malnourished children.[6]

The World Health Organization coordinated the Yemen Health Cluster with 40 member organizations, and together with Health and Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) units, explored the use of oral cholera vaccines (OCV). The WHO reported operating 414 facilities using 406 teams active in 323 districts in Yemen, which included 36 treatment centers for cholera. In the management of cholera, they stated that they trained 900 health workers and ran 139 oral rehydration locations, to treat 700,000 reported cases of the illness.[6] UNICEF reported that they ran awareness campaigns with 20,000 promoters, provided water to more than one million individuals, served as the WaSH lead, and delivered "40 tons of medical equipment including medicine, oral rehydration solution, IV fluids and diarrhea kits".[6]

Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) said it treated at least 103,000 individuals in 37 locations.[6]

Societal factors

On 23 June 2017, Saudi Arabia's crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, authorized a donation in excess of $66 million for cholera relief in Yemen, while continuing its airstrikes and military operations in Yemen.[40]

An aid conference was held in Geneva in April 2017 that raised half of the US$2.1 billion that the UN estimated was needed.[33]

Many Yemeni people could not afford transportation to treatment centers.[41]

Statistics

| Date | Suspected Cholera Cases | Cholera-related deaths | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016-10-10 | 11 | 0 | [42] |

| 2016-10-13 | 186 | 0 | [43] |

| 2016-10-23 | 644 | 3 | [44] |

| 2016-10-30 | 1,410 | 45 | [45] |

| 2016-10-31 | 2,241 | 47 | [46] |

| 2016-11-06 | 2,733 | 51 | [46] |

| 2016-11-17 | 4,825 | 61 | [47] |

| 2016-11-24 | 6,119 | 68 | [48] |

| 2016-12-01 | 7,730 | 82 | [49] |

| 2016-12-08 | 8,975 | 89 | [50] |

| 2016-12-13 | 10,148 | 92 | [51] |

| 2016-12-28 | 12,733 | 97 | [52] |

| 2017-01-10 | 15,468 | 99 | [53] |

| 2017-01-18 | 17,334 | 99 | [54] |

| 2017-02-26 | 20,583 | 103 | [55] |

| 2017-03-07 | 22,181 | 103 | [56] |

| 2017-03-21 | 23,506 | 108 | [57] |

| 2017-04-27 | 26,070 | 120 | [58] |

| 2017-05-20 | 49,495 | 362 | [59] |

| 2017-06-10 | 96,219 | 746 | [60] |

| 2017-06-15 | 140,116 | 989 | [61] |

| 2017-06-22 | 185,301 | 1,233 | [62] |

| 2017-06-29 | 224,989 | 1,416 | [63] |

| 2017-07-06 | 275,987 | 1634 | [64] |

| 2017-07-18 | 351,045 | 1,790 | [65] |

| 2017-07-27 | 408,583 | 1,885 | [66] |

| 2017-10-26 | 862,858 | 2,177 | [67] |

| 2017-12-19 | 1,009,554 [lower-alpha 1] | 2,345 | [68] |

| 2018-01-18 | 1,061,746 | 2,364 | [70] |

| 2018-02-01 | 1,072,744 | 2,368 | [71] |

| 2018-03-01 | 1,089,856 | 2,378 | [72] |

| 2018-04-05 | 1,112,175 | 2,391 | [73] |

| 2018-05-03 | 1,116,350 | 2,395 | [74] |

| 2018-05-20 | 1,126,790 | 2,411 | [69] |

| 2018-07-01 | 1,141,448 | 2,430 | [75] |

| 2018-09-23 | 1,233,666 | 2,630 | [76] |

| 2018-10-21 | 1,291,550 [lower-alpha 2] | 2,604 | [77] |

- Starting in December 2017,[68] The World Health Organization began counting cases of cholera from 27 April 2017 onwards instead of from October 2016.[69] This is resolved by adding 26,070 suspected cholera cases and 120 deaths from December onwards.

- Starting on 8 November 2018, The World Health Organization began counting cases of cholera from 1 January 2018 onwards instead of from 27 April 2017.[77] This is resolved by adding 1,048,701 suspected cholera cases and 2358 deaths from 21 October onwards.

See also

- Famine in Yemen

References

- WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean "Cholera Situation in Yemen September 2019". Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean "Cholera Situation in Yemen September 2019". Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Raslan R, El Sayegh S, Chams S, et al. (2017). "Re-emerging vaccine-preventable diseases in war-affected peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean Region-An update". Front Public Health (Review). 5. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00283. PMC 5661270. PMID 29119098.

- "WHO EMRO | Outbreak update – Cholera in Yemen, 14 April 2019 | Cholera | Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. 14 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Qadri F, Islam T, Clemens JD (November 2017). "Cholera in Yemen – An old foe rearing its ugly head". N. Engl. J. Med. 377 (21): 2005–2007. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1712099. PMID 29091747.

- Federspiel F, Ali M (December 2018). "The cholera outbreak in Yemen: lessons learned and way forward". BMC Public Health (Review). 18 (1): 1338. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6227-6. PMC 6278080. PMID 30514336.

- Snyder, Steven (15 May 2017). "Thousands in Yemen get sick in an entirely preventable cholera outbreak". Public Radio International. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "Access to water continues to be jeopardized for millions of children in war-torn Yemen". UNICEF. 24 July 2018. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Lyons, Kate (12 October 2017). "Yemen's cholera outbreak now the worst in history as millionth case looms". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- "Statement from UNICEF Executive Director Anthony Lake and WHO Director-General Margaret Chan on the cholera outbreak in Yemen as suspected cases exceed 200,000" (Press release). UNICEF. 24 June 2017. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Orkaby, Asher (25 March 2015). "Houthi Who?". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Yemen in Crisis". Council on Foreign Relations. 8 July 2015. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015.

- "Yemeni's Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi arrives in Saudi capital". CBC News. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Yemeni leader Hadi leaves country as Saudi Arabia keeps up air strikes". Reuters. 26 March 2015.

- Finkelstein, Richard. "Medical microbiology". Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Cholera – Vibrio cholerae infection Information for Public Health & Medical Professionals". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 6 January 2015. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Cholera vaccines: WHO position paper" (PDF). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 85 (13): 117–128. 26 March 2010. PMID 20349546. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2015.

- Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Qadri F, et al. (30 June 2012). "Cholera". Lancet. 379 (9835): 2466–76. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60436-x. PMC 3761070. PMID 22748592.

- "Cholera situation in Yemen" (PDF). WHO EMRO. May 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Weekly update: cholera cases in Yemen". WHO EMRO. 15 January 2017. Archived from the original on 22 May 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Yemen: Cholera outbreak response: Situation report No. 3" (PDF). WHO EMRO. 12 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "Cholera cases in Yemen". WHO EMRO. 10 October 2016. Archived from the original on 22 May 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "Update on the cholera situation in Yemen, 30 October 2016". WHO EMRO. 30 October 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Cholera cases in Yemen, 24 November 2016". WHO EMRO. 24 November 2016. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Weekly update: cholera cases in Yemen". WHO EMRO. 22 December 2016. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Weekly update – cholera in Yemen, 22 June 2017". WHO EMRO. 22 June 2017. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Kennedy, Jonathan; Harmer, Andrew; McCoy, David (October 2017). "The political determinants of the cholera outbreak in Yemen". The Lancet Global Health. 5 (10): e970–e971. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30332-7.

- "Update on cholera in Yemen". WHO EMRO. 26 February 2017. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "UN: 1,310 dead in Yemen cholera epidemic". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "Yemen faces world's worst cholera outbreak – UN". BBC News. 25 June 2017. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "Epidemiology bulletin 26, 4 July 2017" (PDF). WHO-EMRO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- McNeil Jr, Donald G (14 August 2017). "More Than 500,000 Infected With Cholera in Yemen". NY Times. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- McKernan, Bethan (29 September 2017). "Yemen's man-made cholera crisis is set to become the worst outbreak on record". The Independent. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Suspected cholera cases in Yemen surpass one million, reports UN health agency". www.news.un.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Yemen: Airstrike hits cholera treatment center in Abs". Médecins Sans Frontières–Doctors Without Borders. 12 June 2018. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Osborne, Samuel (1 March 2017). "Saudi Arabia delaying aid to Yemen is 'killing children', warns Save the Children". The Independent. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Bruwer, Johannes (25 June 2017). "The horrors of Yemen's spiralling cholera crisis". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "What's really stopping a cholera vaccination campaign in Yemen?". IRIN. 17 October 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "WHO EMRO | Fighting the world's largest cholera outbreak: oral cholera vaccination campaign begins in Yemen | Yemen-news | Yemen". WHO EMRO. 10 May 2018. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Gladstone, Rick (23 June 2017). "Saudis, at War in Yemen, Give Country $66.7 Million in Cholera Relief". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (13 July 2017). "'Cholera is everywhere': Yemen epidemic spiralling out of control". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "WHO EMRO - Cholera cases in Yemen - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Update on cholera cases in Yemen - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Cholera update in Yemen, 23 October 2016 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Update on the cholera situation in Yemen, 30 October 2016 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Cholera update in Yemen, 6 November 2016 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Cholera update, Yemen, 17 November 2016 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Cholera cases in Yemen, 24 November 2016 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Additional cholera cases reported in Yemen - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Update on cholera cases reported in Yemen - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - Cholera cases in Yemen, 13 December 2016 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update: Cholera cases in Yemen, 29 December 2016 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update: cholera cases in Yemen, 15 January 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update: cholera cases in Yemen, 23 January 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Update on cholera in Yemen, 26 February 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update: cholera cases in Yemen, 7 March 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update: cholera cases in Yemen, 21 March 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- Back-calculated from http://www.emro.who.int/pandemic-epidemic-diseases/cholera/weekly-update-cholera-in-yemen-20-may-2017.html Archived 3 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - cholera in Yemen, 20 May 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - cholera in Yemen, 10 June 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - cholera in Yemen, 15 June 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - cholera in Yemen, 22 June 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - cholera in Yemen, 29 June 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - cholera in Yemen, 06 July 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - cholera in Yemen, 18 July 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Weekly update - cholera in Yemen, 27 July 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update - cholera in Yemen - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update - cholera in Yemen, 19 December 2017 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO | Outbreak update – Cholera in Yemen, 31 May 2018 | Cholera | Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

The cumulative total of suspected cholera cases, from 27 April 2017 to 20 May 2018, is 1 100 720 and 2 291 associated deaths (case fatality rate 0.21%).

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update - cholera in Yemen, 18 January 2018 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update - cholera in Yemen, 1 February 2018 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update – cholera in Yemen, 1 March 2018 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update – cholera in Yemen, 5 April 2018 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update – cholera in Yemen, 3 May 2018 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update – Cholera in Yemen, 19 July 2018 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update – Cholera in Yemen, 11 October 2018 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "WHO EMRO - Outbreak update – Cholera in Yemen, 8 November 2018 - Cholera - Epidemic and pandemic diseases". WHO EMRO. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.