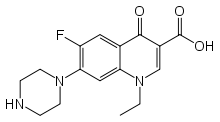

Norfloxacin

Norfloxacin, sold under the brand name Noroxin among others, is an antibiotic[1][2] that belongs to the class of fluoroquinolone antibiotics. It is used to treat urinary tract infections, gynecological infections, inflammation of the prostate gland, gonorrhea and bladder infection.[3][4][5] Eye drops were approved for use in children older than one year of age.[6]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Noroxin, Chibroxin, Trizolin, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a687006 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, ophthalmic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30 to 40% |

| Protein binding | 10 to 15% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3 to 4 hours |

| Excretion | Renal and fecal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.067.810 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H18FN3O3 |

| Molar mass | 319.331 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 220 to 221 °C (428 to 430 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Norfloxacin is associated with a number of rare serious adverse reactions as well as spontaneous tendon ruptures[7] and irreversible peripheral neuropathy. Tendon problems may manifest long after therapy had been completed and in severe cases may result in lifelong disabilities.

It was patented in 1977 and approved for medical use in 1983.[8]

Medical uses

The initial approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1986 encompassed the following indications:

- Uncomplicated urinary tract infections (including cystitis)

- Complicated urinary tract infections (restricted use) [9]

- Uncomplicated urethral and cervical gonorrhea (however this indication is no longer considered to be effective by some experts due to bacterial resistance) [10][11]

- Prostatitis due to Escherichia coli.[12]

- Syphilis treatment: Norfloxacin has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of syphilis. Antimicrobial agents used in high doses for short periods of time to treat gonorrhea may mask or delay the symptoms of incubating syphilis.[13]

Although fluoroquinolones are sometimes used to treat typhoid and paratyphoid fever, norfloxacin had more clinical failures than the other fluoroquinolones (417 participants, 5 trials).[14]

In ophthalmology, Norfloxacin licensed use is limited to the treatment of conjunctival infections caused by susceptible bacteria.[6]

Norfloxacin has been restricted in the Republic of Ireland due to the risks of C. difficile super infections and permanent nerve as well as tendon injuries. It licensed use in acute and chronic complicated kidney infections has been withdrawn as a result.[15]

The European Medicines Agency, also in 2008, had recommended restricting the use of oral norfloxacin to treat urinary infections. CHMP had concluded that the marketing authorizations for norfloxacin, when used in the treatment of acute or chronic complicated pyelonephritis, should be withdrawn because the benefits do not outweigh their risks in this indication. CHMP stated that doctors should not prescribe oral norfloxacin for complicated pyelonephritis and should consider switching patients already taking oral norfloxacin for this type of infection to an alternative antibiotic.[9]

Norfloxacin is used for prevention of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients who have a low ascites fluid protein level, impaired renal function, severe liver disease, have had a prior episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or esophageal variceal bleeding.[16][17][18][19]

Note: Norfloxacin may be licensed for other uses, or restricted, by the various regulatory agencies worldwide.

Contraindications

As noted above, under licensed use, norfloxacin is also now considered to be contraindicated for the treatment of certain sexually transmitted diseases by some experts due to bacterial resistance.[11]

Norfloxacin is contraindicated in those with a history of tendonitis, tendon rupture and those with a hypersensitivity to fluoroquinolones.[20]

There are three contraindications found within the 2008 package[3] insert:

- "Noroxin (norfloxacin) is contraindicated in persons with a history of hypersensitivity, tendinitis, or tendon rupture associated with the use of norfloxacin or any member of the quinolone group of antimicrobial agents."

- "Quinolones, including norfloxacin, have been shown in vitro to inhibit CYP1A2. Concomitant use with drugs metabolized by CYP1A2 (e.g., caffeine, clozapine, ropinirole, tacrine, theophylline, tizanidine) may result in increased substrate drug concentrations when given in usual doses. Patients taking any of these drugs concomitantly with norfloxacin should be carefully monitored."

- "Concomitant administration with tizanidine is contraindicated"

Norfloxacin is also considered to be contraindicated within the pediatric population.

- Pregnancy

Norfloxacin has been reported to rapidly cross the blood-placenta and blood-milk barrier, and is extensively distributed into the fetal tissues.[21] For this reason norfloxacin and other fluoroquinolones are contraindicated during pregnancy due to the risk of spontaneous abortions and birth defects. The fluoroquinolones have also been reported as being present in the mother's milk and are passed on to the nursing child, which may increases the risk of the child suffering an adverse reaction even though the child had never been prescribed or taken any of the drugs found within this class.[22][23] As safer alternatives are generally available norfloxacin is contraindicated during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester. The manufacturer only recommends use of norfloxacin during pregnancy when benefit outweighs risk.[24]

- Children

A 1998 retrospective survey found that numerous side effects have been recorded in reference to the unapproved use of norfloxacin in the pediatric population.[25] Fluoroquinolones are not licensed by the FDA for use in children due to the risk of fatalities[26] as well as permanent injury to the musculoskeletal system, with two exceptions. Ciprofloxacin is being licensed for the treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections and Pyelonephritis due to Escherichia coli and Inhalational Anthrax (post-exposure) and levofloxacin was recently licensed for the treatment of Inhalational Anthrax (post-exposure). However, the Fluoroquinolones are licensed to treat lower respiratory infections in children with cystic fibrosis in the UK.

Adverse effects

In general, fluoroquinolones are well tolerated, with most side-effects being mild to moderate.[27] On occasion, serious adverse effects occur.[28] Common side-effects include gastrointestinal effects such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as headache and insomnia.

The overall rate of adverse events in patients treated with fluoroquinolones is roughly similar to that seen in patients treated with other antibiotic classes.[29][30][31][32] A U.S. Centers for Disease Control study found patients treated with fluoroquinolones experienced adverse events severe enough to lead to an emergency department visit more frequently than those treated with cephalosporins or macrolides, but less frequently than those treated with penicillins, clindamycin, sulfonamides, or vancomycin.[33]

Post-marketing surveillance has revealed a variety of relatively rare but serious adverse effects that are associated with all members of the fluoroquinolone antibacterial class. Among these, tendon problems and exacerbation of the symptoms of the neurological disorder myasthenia gravis are the subject of "black box" warnings in the United States. The most severe form of tendonopathy associated with fluoroquinolone administration is tendon rupture, which in the great majority of cases involves the Achilles tendon. Younger people typically experience good recovery, but permanent disability is possible, and is more likely in older patients.[34] The overall frequency of fluoroquinolone-associated Achilles tendon rupture in patients treated with ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin has been estimated at 17 per 100,000 treatments.[35][36] Risk is substantially elevated in the elderly and in those with recent exposure to topical or systemic corticosteroid therapy. Simultaneous use of corticosteroids is present in almost one-third of quinolone-associated tendon rupture.[37] Tendon damage may manifest during, as well as up to a year after fluoroquinolone therapy has been completed.[38]

FQs prolong the QT interval by blocking voltage-gated potassium channels.[39] Prolongation of the QT interval can lead to torsades de pointes, a life-threatening arrhythmia, but in practice this appears relatively uncommon in part because the most widely prescribed fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) only minimally prolong the QT interval.[40]

Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea may occur in connection with the use of any antibacterial drug, especially those with a broad spectrum of activity such as clindamycin, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones. Fluoroquinoline treatment is associated with risk that is similar to[41] or less [42][43] than that associated with broad spectrum cephalosporins. Fluoroquinoline administration may be associated with the acquisition and outgrowth of a particularly virulent Clostridium strain.[44]

The U.S. prescribing information contains a warning regarding uncommon cases of peripheral neuropathy, which can be permanent.[45] Other nervous system effects include insomnia, restlessness, and rarely, seizure, convulsions, and psychosis[46] Other rare and serious adverse events have been observed with varying degrees of evidence for causation.[47][48][49][50]

Events that may occur in acute overdose are rare, and include renal failure and seizure.[51] Susceptible groups of patients, such as children and the elderly, are at greater risk of adverse reactions during therapeutic use.[27][52][53]

Interactions

The toxicity of drugs that are metabolised by the cytochrome P450 system is enhanced by concomitant use of some quinolones. Quinolones, including norfloxacin, may enhance the effects of oral anticoagulants, including warfarin or its derivatives or similar agents. When these products are administered concomitantly, prothrombin time or other suitable coagulation tests should be closely monitored. Coadministration may dangerously increase coumadin warfarin activity; INR should be monitored closely. [13] They may also interact with the GABA A receptor and cause neurological symptoms; this effect is augmented by certain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.[54] The concomitant administration of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with a quinolone, including norfloxacin, may increase the risk of CNS stimulation and convulsive seizures. Therefore, norfloxacin should be used with caution in individuals receiving NSAIDS concomitantly.[55]

Elevated serum levels of cyclosporine have been reported with concomitant use of cyclosporine with norfloxacin. Therefore, cyclosporine serum levels should be monitored and appropriate cyclosporine dosage adjustments made when these drugs are used concomitantly.

The concomitant administration of quinolones including norfloxacin with glyburide (a sulfonylurea agent) has, on rare occasions, resulted in severe hypoglycemia. Therefore, monitoring of blood glucose is recommended when these agents are co-administered.

Medications

Some quinolones exert an inhibitory effect on the cytochrome P-450 system, thereby reducing theophylline clearance and increasing theophylline blood levels. Coadministration of certain fluoroquinolones and other drugs primarily metabolized by CYP1A2 (e.g. theophylline, methylxanthines, tizanidine) results in increased plasma concentrations and could lead to clinically significant side effects of the coadministered drug. Additionally other fluoroquinolones, especially enoxacin, and to a lesser extent ciprofloxacin and pefloxacin, also inhibit the metabolic clearance of theophylline.[56]

Such drug interactions are associated with the molecular structural modifications of the quinolone ring, specifically interactions involving NSAIDS and theophylline. As such, these drug interactions involving the fluoroquinolones appear to be drug specific rather than a class effect. The fluoroquinolones have also been shown to interfere with the metabolism of caffeine[57] and the absorption of levothyroxine. The interference with the metabolism of caffeine may lead to the reduced clearance of caffeine and a prolongation of its serum half-life, resulting in a caffeine overdose. This may lead to reduced clearance of caffeine and a prolongation of the plasma's half-life that may lead to accumulation of caffeine in plasma when products containing caffeine are consumed while taking norfloxacin. [13]

The use of NSAIDs (Non Steroid Anti Inflammatory Drugs) while undergoing fluoroquinolone therapy is contra-indicated due to the risk of severe CNS adverse reactions, including but not limited to seizure disorders. Fluoroquinolones with an unsubstituted piperazinyl moiety at position 7 have the potential to interact with NSAIDs and/or their metabolites, resulting in antagonism of GABA neurotransmission.[58]

The use of norfloxacin concomitantly has also been associated with transient elevations in serum creatinine in patients receiving cyclosporine, on rare occasions, resulted in severe hypoglycemia with sulfonylurea. Renal tubular transport of methotrexate may be inhibited by concomitant administration of norfloxacin, potentially leading to increased plasma levels of methotrexate. This might increase the risk of methotrexate toxic reactions.

Current or past treatment with oral corticosteroids is associated with an increased risk of Achilles tendon rupture, especially in elderly patients who are also taking the fluoroquinolones.[59]

Overdose

Treatment of overdose includes emptying of the stomach via induced vomiting or by gastric lavage. Careful monitoring and supportive treatment, monitoring of renal and liver function, and maintaining adequate hydration is recommended by the manufacturer. Administration of magnesium, aluminum, or calcium containing antacids can reduce the absorption of norfloxacin.[3]

Mechanism of action

Norfloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that is active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It functions by inhibiting DNA gyrase, a type II topoisomerase, and topoisomerase IV,[60] enzymes necessary to separate bacterial DNA, thereby inhibiting cell division. Norfloxacin does not bind to DNA gyrase but does bind to the substrate DNA.[61] A review in 2001 suggests that cytotoxicity of fluoroquinolones is likely a 2-step process involving (1) conversion of the topoisomerase-quinolone-DNA complex to an irreversible form and (2) generation of a double-strand break by denaturation of the topoisomerase.[62]

Pharmacokinetics

“Absorption of norfloxacin is rapid following single doses of 200 mg, 400 mg and 800 mg. At the respective doses, mean peak serum and plasma concentrations of 0.8, 1.5 and 2.4 μg/mL are attained approximately one hour after dosing. The effective half-life of norfloxacin in serum and plasma is 3–4 hours. Steady-state concentrations of norfloxacin will be attained within two days of dosing. Renal excretion occurs by both glomerular filtration and tubular secretion as evidenced by the high rate of renal clearance (approximately 275 mL/min). Within 24 hours of drug administration, 26 to 32% of the administered dose is recovered in the urine as norfloxacin with an additional 5-8% being recovered in the urine as six active metabolites of lesser antimicrobial potency. Only a small percentage (less than 1%) of the dose is recovered thereafter. Fecal recovery accounts for another 30% of the administered dose. Two to three hours after a single 400-mg dose, urinary concentrations of 200 μg/mL or more are attained in the urine. In healthy volunteers, mean urinary concentrations of norfloxacin remain above 30 μg/mL for at least 12 hours following a 400-mg dose. The urinary pH may affect the solubility of norfloxacin. Norfloxacin is least soluble at urinary pH of 7.5 with greater solubility occurring at pHs above and below this value. The serum protein binding of norfloxacin is between 10 and 15%.” Quoting from the 2009 package insert for Noroxin.[3]

Biotransformation is via the liver and kidneys, with a half-life of 3–4 hours.[63]

History

The first members of the quinolone antibacterial class were relatively low potency drugs such as nalidixic acid, used mainly in the treatment of urinary tract infections owing to their renal excretion and propensity to be concentrated in urine.[6][64] In 1979 the publication of a patent[65] filed by the pharmaceutical arm of Kyorin Seiyaku Kabushiki Kaisha disclosed the discovery of norfloxacin, and the demonstration that certain structural modifications including the attachment of a fluorine atom to the quinolone ring leads to dramatically enhanced antibacterial potency.[66]

In spite of the substantial increase in antibacterial activity of norfloxacin relative to early fluoroquinolones, it did not become a widely used antibiotic. Other companies initiated fluoroquinolone discovery programs in the aftermath of the publication of the norfloxacin patent. Bayer Pharmaceuticals discovered that the addition of a single carbon atom to the norfloxacin structure provided another 4 to 10-fold improvement in activity.[67] Ciprofloxacin reached the market just one year after norfloxacin and achieved sales of 1.5 billion Euros at its peak.[68][69]

Kyorin granted Merck & Company, Inc., an exclusive license (in certain countries, including the United States), to import and distribute Norfloxacin under the brand name Noroxin. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Noroxin for distribution in the United States on October 31, 1986.[70]

Availability

In most countries, all formulations require a prescription. In Colombia (South America) it is marketed under Ambigram from Laboratorios Bussié

Noroxin was discontinued in the US as of April 2014 See the latest package insert for norfloxacin (Noroxin) for additional details. [3]

References

- Nelson, JM.; Chiller, TM.; Powers, JH.; Angulo, FJ. (Apr 2007). "Fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species and the withdrawal of fluoroquinolones from use in poultry: a public health success story". Clin Infect Dis. 44 (7): 977–80. doi:10.1086/512369. PMID 17342653.

- Padeĭskaia, EN. (2003). "[Norfloxacin: more than 20 years of clinical use, the results and place among fluoroquinolones in modern chemotherapy for infections]". Antibiot Khimioter. 48 (9): 28–36. PMID 15002177.

- Merck Sharp & Dohme (September 2008). "TABLETS NOROXIN (NORFLOXACIN)" (PDF). USA: FDA.

- "Norfloxacin" (PDF). Davis. 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Rafalsky, V.; Andreeva, I.; Rjabkova, E.; Rafalsky, Vladimir V (2006). Rafalsky, Vladimir V (ed.). "Quinolones for uncomplicated acute cystitis in women". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (3): CD003597. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003597.pub2. PMID 16856014.

- Merck Sharp & Dohme (September 2000). "Chibroxin (Norfloxacin) Ophthalmic solution" (PDF). USA: FDA.

- Arabyat RM, Raisch DW, McKoy JM, Bennett CL (2015). "Fluoroquinolone-associated tendon-rupture: a summary of reports in the Food and Drug Administration's adverse event reporting system". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 14 (11): 1653–60. doi:10.1517/14740338.2015.1085968. PMID 26393387.

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 500. ISBN 9783527607495.

- "EMEA Restricts Use of Oral Norfloxacin Drugs in UTIs". UK: DGNews. 24 July 2008.

- "Hopkins ABX Guide". ABXguide.org.

- Susan Blank; Julia Schillinger (14 May 2004). "DOHMH ALERT #8:Fluoroquinolone-resistant gonorrhea, NYC". USA: New York County Medical Society. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Naber KG (1991). "The role of quinolones in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis". Infection. 19 Suppl 3: S170–7. doi:10.1007/bf01643692. PMID 1647371.

- http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2004/19384s040,042,043ltr.pdf

- Effa EE, et al. (2011). Bhutta ZA (ed.). "Fluoroquinolones for treating typhoid and paratyphoid fever (enteric fever)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (10): CD004530. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004530.pub4. PMC 6532575. PMID 21975746.

- Clodagh Sheehy (2 August 2008). "Warning over two types of antibiotic". Republic of Ireland. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- Runyon BA (1986). "Low-protein-concentration ascitic fluid is predisposed to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis". Gastroenterology. 91 (6): 1343–6. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(86)90185-X. PMID 3770358.

- Fernández J, Navasa M, Planas R, et al. (2007). "Primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis delays hepatorenal syndrome and improves survival in cirrhosis". Gastroenterology. 133 (3): 818–24. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.065. PMID 17854593.

- Grangé JD, Roulot D, Pelletier G, et al. (1998). "Norfloxacin primary prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with ascites: a double-blind randomized trial". J. Hepatol. 29 (3): 430–6. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(98)80061-5. PMID 9764990.

- Chavez-Tapia, NC; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T; Tellez-Avila, FI; Soares-Weiser, K; Uribe, M (8 September 2010). "Antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD002907. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002907.pub2. PMID 20824832.

- "19-384/S027" (PDF). USA: FDA. 1995.

- http://drugsafetysite.com/norfloxacin/ referencing: T.P. Dowling, personal communication, Merck & Co, Inc., 1987

- Shin HC, Kim JC, Chung MK, et al. (September 2003). "Fetal and maternal tissue distribution of the new fluoroquinolone DW-116 in pregnant rats". Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 136 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2003.08.004. ISSN 1532-0456. PMID 14522602.

- Dan M, Weidekamm E, Sagiv R, Portmann R, Zakut H (February 1993). "Penetration of fleroxacin into breast milk and pharmacokinetics in lactating women". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37 (2): 293–6. doi:10.1128/AAC.37.2.293. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 187655. PMID 8452360.

- "Norfloxacin (Noroxin) Use During Pregnancy".

- Pariente-Khayat, A.; Vauzelle-Kervroedan, F.; d'Athis, P.; Bréart, G.; Gendrel, D.; Aujard, Y.; Olive, G.; Pons, G. (May 1998). "[Retrospective survey of fluoroquinolone use in children]". Arch Pediatr. 5 (5): 484–8. doi:10.1016/S0929-693X(99)80311-X. PMID 9759180.

- Karande SC, Kshirsagar NA (February 1992). "Adverse drug reaction monitoring of ciprofloxacin in pediatric practice". Indian Pediatr. 29 (2): 181–8. ISSN 0019-6061. PMID 1592498.

- Owens RC, Ambrose PG (July 2005). "Antimicrobial safety: focus on fluoroquinolones". Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 Suppl 2: S144–57. doi:10.1086/428055. PMID 15942881.

- De Sarro A, De Sarro G (March 2001). "Adverse reactions to fluoroquinolones. an overview on mechanistic aspects". Curr. Med. Chem. 8 (4): 371–84. doi:10.2174/0929867013373435. PMID 11172695.

- "www.fda.gov".

- Skalsky K, Yahav D, Lador A, Eliakim-Raz N, Leibovici L, Paul M (April 2013). "Macrolides vs. quinolones for community-acquired pneumonia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19 (4): 370–8. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03838.x. PMID 22489673.

- Falagas ME, Matthaiou DK, Vardakas KZ (December 2006). "Fluoroquinolones vs beta-lactams for empirical treatment of immunocompetent patients with skin and soft tissue infections: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Mayo Clin. Proc. 81 (12): 1553–66. doi:10.4065/81.12.1553. PMID 17165634.

- Van Bambeke F, Tulkens PM (2009). "Safety profile of the respiratory fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin: comparison with other fluoroquinolones and other antibacterial classes". Drug Saf. 32 (5): 359–78. doi:10.2165/00002018-200932050-00001. PMID 19419232.

- Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS (September 2008). "Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events". Clin. Infect. Dis. 47 (6): 735–43. doi:10.1086/591126. PMID 18694344.

- Kim GK (April 2010). "The Risk of Fluoroquinolone-induced Tendinopathy and Tendon Rupture: What Does The Clinician Need To Know?". J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 3 (4): 49–54. PMC 2921747. PMID 20725547.

- Sode J, Obel N, Hallas J, Lassen A (May 2007). "Use of fluroquinolone and risk of Achilles tendon rupture: a population-based cohort study". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63 (5): 499–503. doi:10.1007/s00228-007-0265-9. PMID 17334751.

- Owens RC, Ambrose PG (July 2005). "Antimicrobial safety: focus on fluoroquinolones". Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 Suppl 2: S144–57. doi:10.1086/428055. PMID 15942881.

- Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG (October 2005). "Musculoskeletal injury associated with fluoroquinolone antibiotics". Clin Plast Surg. 32 (4): 495–502, vi. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2005.05.004. PMID 16139623.

- Saint F, Gueguen G, Biserte J, Fontaine C, Mazeman E (September 2000). "[Rupture of the patellar ligament one month after treatment with fluoroquinolone]". Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar mot (in French). 86 (5): 495–7. PMID 10970974.

- Heidelbaugh JJ, Holmstrom H (April 2013). "The perils of prescribing fluoroquinolones". J Fam Pract. 62 (4): 191–7. PMID 23570031.

- Rubinstein E, Camm J (April 2002). "Cardiotoxicity of fluoroquinolones". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49 (4): 593–6. doi:10.1093/jac/49.4.593. PMID 11909831.

- Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, et al. (September 2013). "Community-associated Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotics: a meta-analysis". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68 (9): 1951–61. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt129. PMID 23620467.

- Slimings C, Riley TV (December 2013). "Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: update of systematic review and meta-analysis". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69 (4): 881–91. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt477. PMID 24324224.

- "Data Mining Analysis of Multiple Antibiotics in AERS".

- Vardakas KZ, Konstantelias AA, Loizidis G, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME (November 2012). "Risk factors for development of Clostridium difficile infection due to BI/NAP1/027 strain: a meta-analysis". Int. J. Infect. Dis. 16 (11): e768–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2012.07.010. PMID 22921930.

- "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires label changes to warn of risk for possibly permanent nerve damage from antibacterial fluoroquinolone drugs taken by mouth or by injection".

- Galatti L, Giustini SE, Sessa A, et al. (March 2005). "Neuropsychiatric reactions to drugs: an analysis of spontaneous reports from general practitioners in Italy". Pharmacol. Res. 51 (3): 211–6. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2004.08.003. PMID 15661570.

- Babar SM (October 2013). "SIADH associated with ciprofloxacin". Ann Pharmacother. 47 (10): 1359–63. doi:10.1177/1060028013502457. PMID 24259701.

- Rouveix, B. (Nov–Dec 2006). "[Clinically significant toxicity and tolerance of the main antibiotics used in lower respiratory tract infections]". Med Mal Infect. 36 (11–12): 697–705. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2006.05.012. PMID 16876974.

- Mehlhorn AJ, Brown DA (November 2007). "Safety concerns with fluoroquinolones". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 41 (11): 1859–66. doi:10.1345/aph.1K347. PMID 17911203.

- Jones SF, Smith RH (March 1997). "Quinolones may induce hepatitis". BMJ. 314 (7084): 869. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7084.869. PMC 2126221. PMID 9093098.

- Nelson, Lewis H.; Flomenbaum, Neal; Goldfrank, Lewis R.; Hoffman, Robert Louis; Howland, Mary Deems; Neal A. Lewin (2006). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 978-0-07-143763-9.

- Iannini PB (June 2007). "The safety profile of moxifloxacin and other fluoroquinolones in special patient populations". Curr Med Res Opin. 23 (6): 1403–13. doi:10.1185/030079907X188099. PMID 17559736.

- Farinas, Evelyn R; PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH (1 March 2005). "Consult: One-Year Post Pediatric Exclusivity Postmarketing Adverse Events Review" (PDF). USA: FDA. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- Brouwers JR, JR (July 1992). "Drug interactions with quinolone antibacterials". Drug Saf. 7 (4): 268–81. doi:10.2165/00002018-199207040-00003. ISSN 0114-5916. PMID 1524699.

- http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2006/019384s045LTR.pdf

- Janknegt R, R (November 1990). "Drug interactions with quinolones". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 26 Suppl D: 7–29. doi:10.1093/jac/26.suppl_D.7. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 2286594.

- Harder S, Fuhr U, Staib AH, Wolff T (November 1989). "Ciprofloxacin-caffeine: a drug interaction established using in vivo and in vitro investigations" (Free full text). Am. J. Med. 87 (5A): 89S–91S. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(89)90031-4. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 2589393.

- Domagala JM, JM (April 1994). "Structure-activity and structure-side-effect relationships for the quinolone antibacterials". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33 (4): 685–706. doi:10.1093/jac/33.4.685. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 8056688.

- van der Linden PD, Sturkenboom MC, Herings RM, Leufkens HM, Rowlands S, Stricker BH (August 2003). "Increased risk of achilles tendon rupture with quinolone antibacterial use, especially in elderly patients taking oral corticosteroids". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (15): 1801–7. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.15.1801. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 12912715.

- Drlica K, Zhao X (1 September 1997). "DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones". Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 61 (3): 377–92. PMC 232616. PMID 9293187.

- Shen LL, Pernet AG (1985). "Mechanism of inhibition of DNA gyrase by analogues of nalidixic acid: the target of the drugs is DNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82 (2): 307–11. Bibcode:1985PNAS...82..307S. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.2.307. PMC 397026. PMID 2982149.

- Hooper, David (2001). "Mechanisms of action of antimicrobials: focus on fluoroquinolones". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 32: S9–S15. doi:10.1086/319370. PMID 11249823.

- "Norfloxacin". 10 June 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Mayrer AR, Andriole VT (January 1982). "Urinary tract antiseptics". Med. Clin. North Am. 66 (1): 199–208. doi:10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31453-5. PMID 7038329.

- "Patent US4146719 - Piperazinyl derivatives of quinoline carboxylic acids - Google Patents".

- "aac.asm.org".

- Wise R, Andrews JM, Edwards LJ (April 1983). "In vitro activity of Bay 09867, a new quinoline derivative, compared with those of other antimicrobial agents". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 23 (4): 559–64. doi:10.1128/aac.23.4.559. PMC 184701. PMID 6222695.

- "www.sec.gov".

- "Cipro". USA: Prescription Access. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- "Determination That NOROXIN (Norfloxacin) Tablets, 400 Milligrams, Was Not Withdrawn From Sale for Reasons of Safety or Effectiveness". Federal Register. 2017-12-12. Retrieved 2018-11-07.