Timeline of cholera

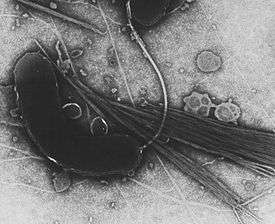

This is a timeline of cholera, a disease caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae.

Summary

| Time period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 5th century BC | Cholera most likely originates in the subcontinent of India, where most of the cholera pandemics will later start.[1][2] |

| 1816–1923 | The first six cholera pandemics occurred consecutively and continuously over time. Increased commerce, migration, and pilgrimage are credited for its transmission.[3] |

| 1879–1883 | Major scientific breakthroughs towards the treatment of cholera develop: the first immunization by Pasteur, the development of the first cholera vaccine, and the identification of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae by Filippo Pacini and Robert Koch. |

| 1945–1948 | The World Health Organization (WHO) is founded. |

| 1961 onwards | After a long hiatus, the seventh major cholera outbreak occurs. Oral rehydration therapy is introduced in the late 1970s.[4] |

| Recent | The seventh cholera pandemic continues, although on a smaller scale, with outbreaks across the developing world. Epidemics occur after war, civil unrest, or natural disasters, when water and food supplies become contaminated with Vibrio cholerae, and also due to crowded living conditions and poor sanitation.[5] |

Full timeline

| Year/Period | Event type | Event | Present-day geographic location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 460–377 BCE | Scientific development | Greek physician Hippocrates is considered the first to mention the term "cholera" in his writings, although the exact disease he refers to is unknown.[6][7] | Greece |

| 1563 | Scientific development | Cholera is first recorded in a medical report.[8] | India |

| 1817–1824 | Epidemic | The first cholera pandemic begins near Calcutta, reaching most of Asia. It is thought to have killed over 100,000 people.[9] | India, Thailand, Philippines, Java, Oman, China, Japan, Persian Gulf, Iraq, Syria, Transcaucasia, Astrakhan (Russia), Zanzibar, and Mauritius. |

| 1819 | Epidemic | Cholera epidemic reaches the island of Java from Bengal.[10] | Indonesia |

| 1848 | The Public Health Act 1848 establishes the first local boards of health in England and Wales. The boards would ensure proper drainage in homes and dependable water supplies.[11] | England and Wales | |

| 1829–1851 | Epidemic | The second cholera pandemic, also known as the Asiatic Cholera Pandemic, starts, likely along the Ganges river. It is the first to reach Europe and North America. As previously, fatalities reach six figures.[9] | India, western and eastern Asia, Europe, Americas. |

| 1830-1831 | Epidemic | Cholera epidemics across Europe give rise to the Cholera Riots in Russia[12] and England.[13] | Europe |

| 1831 | Scientific development | Scottish physician William Brooke O'Shaughnessy notices that the composition for the stool water in cholera patients is very similar to that of their blood plasma. These values are found close to those of normal controls, except that the patients have markedly reduced water content. From this data, O'Shaughnessy suggests that replacing water with salt would be beneficial to them.[14] | Great Britain |

| 1832 | Scientific development (treatment) | Medical pioneer Thomas Latta develops the first intravenous saline drip.[15] | Scotland (Leith) |

| 1832 | Epidemic | Cholera claims 6,536 victims in London and 20,000 in Paris (out of a population of 650,000), and is responsible for about 100,000 deaths in France as a whole. The epidemic reaches Russia, Quebec, Ontario and New York in the same year. In Portugal, cholera is brought to Oporto on the boats that carry troops from Ostend to help the Liberal army during the Liberal Wars. From Oporto, cholera spreads throughout the country, and more than 40,000 people perish. It is calculated that cholera killed more people than the war itself.[16] | Europe, North America |

| 1851–1938 | Organization | Due to the cholera pandemics, the International Sanitary Conferences are held with the objective to standardize international quarantine regulations against the spread of cholera and other diseases.[17] | Paris, Constantinople, Vienna, Washington, Rome, Venice, Dresden |

| 1852–1860 | Epidemic | The third cholera pandemic starts along the Ganges delta. Millions are infected in Russia. The death toll reaches one million.[9] | Asia, Europe, Africa and North America |

| 1853 | Epidemic | Third cholera pandemic: The Copenhagen cholera outbreak kills almost 5,000 people in less than three months.[18] | Denmark |

| 1854 | Scientific development | Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini publishes his paper "Microscopical observations and pathological deductions on cholera" in which he describes his discovery of a microorganism which he names Vibrio, and its relation to cholera. Pacini becomes the first to isolate the cholera bacterium Vibrio cholerae.[19][20] | Italy |

| 1854 | Epidemic | The cholera epidemic reaches China, Japan; and Mauritius, where four outbreaks occur until 1862.[21] In London, the Broad Street cholera outbreak kills at least 500 people.[22] | China, Japan, Mauritius, England |

| 1854 | Scientific development | The first demonstration, performed by John Snow during an epidemic in London, that the transmission of cholera is significantly reduced when uncontaminated water is provided to the population.[5][8] | England |

| 1854 | Organization | Cholera Hospital is established. It is built to treat cholera patients who are denied admittance to City Hospital in Manhattan during cholera epidemics in the same year.[23][24] | United States (New York City) |

| 1856–1857 | Epidemic | Cholera is recorded in several parts of Central America and Guyana.[21] | Central America, South America |

| 1863–1875 | Epidemic | The fourth cholera pandemic starts, again in the Ganges delta.[9] | Asia, Middle East, Russia, Europe, Africa and North America |

| 1865 | Epidemic | Fourth cholera pandemic: The Mecca pilgrimage becomes the scene of a major epidemic. It is calculated that 30,000 deaths occur out of 90,000 pilgrims.[21] | Saudi Arabia (Mecca) |

| 1865–1866 | Epidemic | Fourth cholera pandemic: Cholera arrives again in the United States. Deplorable sanitary conditions prove favorable for the spread of the disease.[21] | United States |

| 1869 | Epidemic | Fourth cholera pandemic: About 70,000 people are reported dead in what is then called Zanzibar.[21] | Tanzania |

| 1879 | Scientific development | Louis Pasteur succeeds in immunizing chickens against cholera.[25] | France |

| 1881–1896 | Epidemic | The fifth cholera pandemic begins in India. It is the first to reach South America.[9] | Asia, Africa, Russia, Europe, South America |

| 1883 | Scientific development | The identification of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae by Robert Koch takes place. Although not the first description, the discovery of the cholera organism is credited to Koch, who independently identifies the bacterium during an outbreak in Egypt.[5] | |

| 1885 | Scientific development (drug) | Spanish physician Jaume Ferran i Clua develops a cholera vaccine, which is the first to immunize humans against a bacterial disease. Ferrán vaccinates about 50,000 people in Valencia during a cholera epidemic.[16][26] | Spain |

| 1892 | Scientific development (drug) | The Russian bacteriologist Waldemar Haffkine, working at the Pasteur Institute, announces a new cholera vaccine.[27][28] | |

| 1899–1923 | Epidemic | The sixth pandemic kills more than 800,000 people in India, where it begins.[9] | India, Middle East, North Africa, Eastern Europe and Russia. |

| 1923 | Scientific development | The first studies on cholera phages are carried out. They are summarized in 1959.[29][20] | |

| 1935 | Epidemic | The new cholera biotype El Tor causes a major outbreak and epidemic in the Celebes Islands. The El Tor biotype (strain M66-2) is later isolated in Indonesia during an outbreak in 1937.[29] | Indonesia |

| 1935 | Scientific development | The serological classification of Vibrio cholerae is first described.[30] | |

| 1948 | Organization | The formation of the World Health Organization (WHO).[17] | Geneva |

| 1948 | Scientific development (drug) | The antibiotic tetracycline is introduced. It is used for treating several types of infections caused by susceptible bacteria, including Vibrio cholerae.[31] | |

| 1951–1959 | Scientific development | Indian pathologist Sambhu Nath De discovers that cholera is caused by a potent exotoxin (cholera toxin) affecting intestinal permeability. Nath De also demonstrates that bacteria-free culture filtrates of Vibrio cholerae are enterotoxic. Sambu Nath De also develops a reproducible animal model for the disease. These works are considered milestones in the history of the fight against cholera.[4] | |

| 1952 | Scientific development (drug) | Erythromycin is introduced. It is used for the treatment of cholera.[32][33] | |

| 1961–present | Epidemic | The seventh cholera pandemic starts in Indonesia. It continues today, albeit at a much smaller scale.[9] | Asia, Africa, Americas, Europe, Oceania |

| 1967 | Scientific development (drug) | Doxycycline is introduced as an antibiotic. It proves to be an effective treatment for cholera.[34][33] | |

| 1968 | Scientific development (drug) | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is introduced. It is used for treating cholera, as well as multiple other diseases.[35][36] | |

| 1971–2012 | Epidemic | Seventh cholera pandemic: Cholera is first reported in Cameroon in 1971. In the period between 2000 and 2012, 43,474 cholera cases are reported: 1,748 are fatal (mean annual case fatality ratio of 7.9%), with an attack rate of 17.9 reported cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year.[37] | Cameroon |

| 1974 | Scientific development | Researchers show that more than 108 Vibrio cholerae cells are required to induce infection and diarrhea.[30] | |

| 1976 | Scientific development | Researchers report that a combination of Vibrio cholerae O1 antigens such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and cholera toxin (CT) or choleragenoid (now termed Cholera Toxin B or CTB) induces more than 100-fold greater protection of rabbits against a challenge with live vibrios than does vaccination with either of the two antigens alone.[38] | |

| 1979 | Scientific development (treatment) | Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is introduced as a technique of fluid replacement used to prevent or treat dehydration especially due to diarrhea. ORT rapidly becomes the cornerstone of programs for the control of diarrheal diseases. Oral rehydration therapy dramatically brought down the cholera case fatality rate from 30% in 1980 to around 3.6% in 2000.[4][39] | |

| 1984 | Scientific development (drug) | The FDA approves serotonin antagonist ondansetron. Ondansetron diminishes cholera toxin-evoked secretion.[40][41] | United States |

| 1984 | Epidemic | Seventh cholera pandemic: The cholera epidemic reaches Mali. 1,793 cases and 406 deaths are reported.[42] | Mali |

| 1986 | Scientific development (drug) | The FDA approves antibacterial norfloxacin. It proves to be effective for the treatment of cholera.[43] | United States |

| 1986 | Scientific development | The molecular technique for bacterial identification known as ribotyping is invented. It is used for characterizing cholera strains.[44][29] | |

| 1990 (circa) | Scientific development | The pulsed-field gel electrophoresis technique is first described. It is used to subtype bacterial strains. PFGE would be useful for the identification of the spread of specific clones in many cholera outbreak investigations.[45][29] | |

| 1990 (circa) | Scientific development | Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis is first described. RAPD would be used for characterizing representative strains of Vibrio cholerae.[46][29] | |

| 1991 | Scientific development (drug) | The oral cholera vaccine Dukoral is introduced. It is manufactured by Crucell.[47] | Netherlands |

| 1992–1993 | Epidemic | A new strain of cholera, Vibrio cholerae serogroup O139 Bengal, emerges and causes outbreaks in Bangladesh and India. Disease from this strain becomes endemic in at least 11 countries.[5] | |

| 1994 | Epidemic | Seventh cholera pandemic: Cholera cases are notified from 94 countries, the highest ever number of countries in one year.[30] | |

| 1998 | Scientific Development | Multilocus sequence typing analysis (MLST) is first described. MLST has better discriminatory ability for typing Vibrio cholerae than pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and provides a measure of phylogenetic relatedness.[48][29] | |

| 2001 | Scientific development (drug) | The FDA approves serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonist granisetron. Granisetron markedly diminishes cholera toxin-evoked secretion.[40][41] | United States |

| 2007 | Scientific development (drug) | Researchers from the University of Tokyo develop a type of rice that carries the cholera vaccine.[49][50] | Japan |

| 2007 | Epidemic | Iraq cholera outbreak: 4,667 cases reported. The median age of the patients is 11 years.[51] | Iraq |

| 2008 | Epidemic | Zimbabwean cholera outbreak: 98,741 cases and 4,293 deaths reported.[52][53] | Zimbabwe, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa and Zambia. |

| 2009 | Epidemic | The World Health Organization reports more than 220,000 cases of cholera and almost 5,000 deaths worldwide.[54] | |

| 2009 | Scientific development (drug) | The oral cholera vaccine Shanchol is introduced. It contains dead whole cells of Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139. Shanchol is manufactured by Shantha Biotechnics.[47][55] | India |

| 2009 | Epidemic | A cholera outbreak in Papua New Guinea results in over 15,000 cases and more than 500 deaths.[56] | Papua New Guinea |

| 2010–present | Epidemic | The Haiti cholera outbreak kills over 9,500 people across four countries.[57] | Haiti, Dominican Republic, Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela and Florida (U.S.) |

| 2011 | Scientific development | The multi-virulence locus sequencing typing technique is first described. MVLST is used for determining the genetic variation and relatedness of Vibrio cholerae strains of different serogroups.[58][29] | |

| 2012 | Epidemic | Sierra Leonean cholera outbreak: At least 392 people are reportedly killed and more than 25,000 others are infected.[59][60] | Sierra Leone, Guinea |

| 2014–2015 | Epidemic | A cholera outbreak in Africa. 1,475 reported deaths.[61] 84,675 reported cases.[61] | Ghana, Nigeria, Niger, Togo, Benin, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ivory Coast, Chad, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea |

| 2015 | Scientific development (drug) | The oral cholera vaccine Euvichol is introduced. Euvichol is manufactured by EuBiologics.[47] | South Korea |

| 2016 | Scientific development (drug) | The FDA approves Vaxchora for the prevention of cholera.[62] | United States |

| 2015–Present | Epidemic | Over 500,000 cases[63] with over 2000 deaths[64] amid widespread malnutrition during the Yemen Civil War.[65] | Yemen |

References

- Fabini, D. Orata; Keim, Paul S.; Boucher, Yan (2014). "The 2010 Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: How Science Solved a Controversy". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (4): e1003967. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003967. PMC 3974815. PMID 24699938.

- Alam, Munirul; Orata, Fabini D.; Boucher, Yan (2015). "The out-of-the-delta hypothesis: dense human populations in low-lying river deltas served as agents for the evolution of a deadly pathogen". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 1120. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01120. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 4609888. PMID 26539168.

- Tatem, A.J.; Rogers, D.J.; Hay, S.I. (2006). Global Transport Networks and Infectious Disease Spread. Advances in Parasitology. 62. pp. 293–343. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(05)62009-X. ISBN 9780120317622. PMC 3145127. PMID 16647974.

- Nair, G Balakrish; Narain, Jai P (2010). "From endotoxin to exotoxin: De's rich legacy to cholera". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 88 (3): 237–240. doi:10.2471/BLT.09.072504. PMC 2828792. PMID 20428396. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Handa, Sanjeev (February 16, 2016). "Cholera: Background". MedScape. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Kousoulis, AA (2012). "Etymology of Cholera". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (3): 540. doi:10.3201/eid1803.111636. PMC 3309598. PMID 22377194.

- Kousoulis, Antony E. (March 1, 2012). "Etymology of cholera". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (3): 540. doi:10.3201/eid1803.111636. PMC 3309598. PMID 22377194.

- "Origins of Cholera". choleraandthethames.co.uk. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- "Cholera's seven pandemics". CBC News. May 9, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Macpherson, John (1869). On the Early Seats of Cholera in India, and in the East: With Reference to ... Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Haley, Bruce (October 11, 2002). "Health and Hygiene in the Nineteenth Century". Retrieved January 26, 2017.

The Public Health Bill, passed in 1848 because of the efforts of reformers like Smith and Chadwick, empowered a central authority to set up local boards, whose duty was to see that new homes had proper drainage and that local water supplies were dependable. The boards were also authorized to regulate the disposal of waste and to supervise the construction of burial grounds.

- "Russia, cholera riots of 1830 –1831" (PDF). University of New Mexico. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Gill, G; Burrell, S; Brown, J (2001). "Fear and frustration--the Liverpool cholera riots of 1832". The Lancet. 358 (9277): 233–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05463-0. PMID 11476860.

- Lifshitz, Fima (1994-11-28). Childhood Nutrition. ISBN 9780849327643.

- MacGillivray, Neil (September 1, 2009). "Dr Thomas Latta: the father of intravenous infusion therapy". Journal of Infection Prevention. 10: S3–S6. doi:10.1177/1757177409342141. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- De Almeida, M. A. P. (2012). "The Portuguese cholera morbus epidemic of 1853–56 as seen by the press". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. The Royal Society. 66 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2011.0001. PMID 22530391.

- Markel, Howard (January 7, 2014). "Worldly approaches to global health: 1851 to the present" (PDF). University of Michigan. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- Rossel, Sven Hakon (1996). Hans Christian Andersen: Danish Writer and Citizen of the World. p. 55. ISBN 978-9051839487. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- "Who first discovered cholera?". UCLA. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Felsenfeld, O (1966). "A Review of Recent Trends in Cholera Research and Control". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 34 (2): 161–95. PMC 2475942. PMID 5328492.

- Barua, Dhiman; Greenough, William B. (1992-09-30). Cholera. ISBN 9780306440779. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Broad Street Pump Outbreak". UCLA Department of Epidemiology. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- "Cholera Hospital". tophealthclinics.com. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Adler, Richard (2013-07-19). Cholera in Detroit: A History. p. 135. ISBN 9780786474790. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "First Laboratory Vaccine". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- "Ferrán Vaccinating for Cholera". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- BAKALAR, NICHOLAS (October 2012). "Milestones in Combating Cholera". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Waldemar Haffkine". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Rahaman, Md. Habibur; Islam, Tarequl; Colwell, Rita R.; Alam, Munirul (2015). "Molecular tools in understanding the evolution of Vibrio cholera". Frontiers in Microbiology. ResearchGate. 6: 1040. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01040. PMC 4594017. PMID 26500613. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Vibrio cholerae: Description Taxonomy and serological classification" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "tetracycline". MedicineNet. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Wise, Robert I. (1955). "Origin of Erythromycin-Resistant Strains of Micrococcus Pyogenes in Infections". AMA Archives of Internal Medicine. 95 (3): 419–26. doi:10.1001/archinte.1955.00250090057008. PMID 14349420. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "Antibiotic Treatment". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "New Research on Doxycycline". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Ho, Joanne M.-W. (2011). "Considerations when prescribing trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 183 (16): 1851–8. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111152. PMC 3216436. PMID 21989472.

- "Co-trimoxazole". Drugs.com. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Franky, Simon; Baonga Ba Pouth; Teboh, Andrew; Yang, Yang; Arabi, Mouhaman; D. Sugimoto, Jonathan; Glenn Morris Jr., John; Mbam, Leonard M.; Blackburn, Jason K.; Morris, Lillian; T. Kracalik, Ian; Liang, Song; Ngwa, Moise C (2016). "Cholera in Cameroon, 2000-2012: Spatial and Temporal Analysis at the Operational (Health District) and Sub Climate Levels". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (11): e0005105. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005105. PMC 5113893. PMID 27855171.

- Alexander, T. S. (2014). "Critical Analysis of Compositions and Protective Efficacies of Oral Killed Cholera Vaccines". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. United States National Library of Medicine. 21 (9): 1195–205. doi:10.1128/CVI.00378-14. PMC 4178583. PMID 25056361.

- Victora, CG; Bryce, J; Fontaine, O; Monasch, R (2000). "Reducing deaths from diarrhoea through oral rehydration therapy". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 78 (10): 1246–55. doi:10.1590/S0042-96862000001000010. PMC 2560623. PMID 11100619.

- Smith, Howard S.; Cox, Lorraine R.; Smith, Eric J. (2012-09-14). "5-HT3 receptor antagonists for the treatment of nausea/vomiting". Annals of Palliative Medicine. 1 (2): 115–120. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Sjöqvist, A; Cassuto, J; Jodal, M; Lundgren, O. (1992). "Actions of serotonin antagonists on cholera-toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion". Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 145 (3): 229–37. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1992.tb09360.x. PMID 1355626.

- Tauxe, Robert V.; Holmberg, Scott D.; Dodin, Andre; Wells, Joy V.; Blake, Paul A. (1988). "Epidemic cholera in Mali: High mortality and multiple routes of transmission in a famine area". Epidemiology and Infection. 100 (2): 279–89. doi:10.1017/s0950268800067418. PMC 2249226. PMID 3356224.

- "NORFLOXACIN". United States National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Dalsgaard, A; Echeverria, P; Larsen, J L; Siebeling, R; Serichantalergs, O; Huss, H H (1995). "Application of ribotyping for differentiating Vibrio cholerae non-O1 isolated from shrimp farms in Thailand". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 61 (1): 245–51. PMC 167279. PMID 7534053.

- Filippis, Ivano; McKee, Marian L. (2012-11-07). Molecular Typing in Bacterial Infections. p. 62. ISBN 9781627031851. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Chhotray, GP; Pal, BB; Khuntia, HK; Chowdhury, NR; Chakraborty, S; Yamasaki, S; Ramamurthy, T; Takeda, Y; Bhattacharya, SK; Nair, GB. (2002). "Incidence and molecular analysis of Vibrio cholerae associated with cholera outbreak subsequent to the super cyclone in Orissa, India". Epidemiology and Infection. 128 (2): 131–8. doi:10.1017/S0950268801006720. PMC 2869804. PMID 12002529.

- "Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV): What You Need To Know" (PDF). stopcholera.org. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Faruque, Shah M.; Nair, G. Balakrish (2008). Vibrio Cholerae: Genomics and Molecular Biology. ISBN 9781904455332. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Kotar, S.L.; Gessler, J.E. (2014-03-08). Cholera: A Worldwide History. p. 288. ISBN 9781476613642. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Sinha, Kounteya (June 13, 2007). "Breakthrough in cholera cure". The Times of India. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Khwaif, JM; Hayyawi, AH; Yousif, TI (2010). "Cholera outbreak in Baghdad in 2007: an epidemiological study". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 16 (6): 584–9. doi:10.26719/2010.16.6.584. PMID 20799583.

- "Epidemiological Bulletin Number 41" (PDF). World Health Organization. January 10, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- "Zimbabwe cholera 'to top 100,000'". BBC. 26 May 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Schaetti, C; Weiss, MG; Ali, SM; Chaignat, CL; Khatib, AM; Reyburn, R; Duintjer Tebbens, RJ; Hutubessy, R (2012). "Costs of Illness Due to Cholera, Costs of Immunization and Cost-Effectiveness of an Oral Cholera Mass Vaccination Campaign in Zanzibar". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (10): e1844. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001844. PMC 3464297. PMID 23056660.

- "Vaccines". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Horwood, PF; Karl, S; Mueller, I; Jonduo, MH; Pavlin, BI; Dagina, R; Ropa, B; Bieb, S; Rosewell, A; Umezaki, M; Siba, PM; Greenhill, AR (2014). "Spatio-temporal epidemiology of the cholera outbreak in Papua New Guinea, 2009-2011". BMC Infectious Diseases. 14: 449. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-449. PMC 4158135. PMID 25141942.

- "Haiti cholera outbreak". Pan American Health Organization. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Advances in Vibrio Research and Application: 2012 Edition. 2012-12-26. p. 80. ISBN 9781464997617. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Cholera outbreak easing". IRIN. 2012-09-23. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "Cholera - rising with the downpours". IRIN. 2012-08-30. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "Cholera in Ghana" (PDF). UNICEF. 15 November 2014.

- "Vaxchora" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "Cholera count reaches 500 000 in Yemen". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- Jr, Donald G. Mcneil (2017-08-14). "More Than 500,000 Infected With Cholera in Yemen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- Yemen cholera cases pass 200,000, BBC News, June 24, 2017

This article is issued from

Wikipedia.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.