WASH

WASH (or Watsan, WaSH) is an acronym that stands for "water, sanitation and hygiene". Universal, affordable and sustainable access to WASH is a key public health issue within international development and is the focus of Sustainable Development Goal 6.[1]

.jpg)

Several international development agencies assert that attention to WASH can also improve health, life expectancy, student learning, gender equality, and other important issues of international development.[2] Access to WASH includes safe water, adequate sanitation and hygiene education. This can reduce illness and death, and also reduce poverty and improve socio-economic development.

In 2015 the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that "1 in 3 people, or 2.4 billion, are still without sanitation facilities" while 663 million people still lack access to safe and clean drinking water.[3][4] In 2017, this estimate changed to 2.3 billion people without sanitation facilities and 844 million people without access to safe and clean drinking water.[5]

Lack of sanitation contributes to about 700,000 child deaths every year due to diarrhea, mainly in developing countries. Chronic diarrhea can have long-term negative effects on children, in terms of both physical and cognitive development.[6] In addition, lack of WASH facilities can prevent students from attending school, impose an unusual burden on women and reduce work productivity.[7]

Background

.jpg)

The concept of WASH groups together water supply, sanitation, and hygiene because the impact of deficiencies in each area overlap strongly. Addressing these deficiencies together can achieve a strong positive impact on public health.

Since 1990, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene has regularly produced estimates of global WASH progress.[5] The JMP was responsible for monitoring the UN's Millennium Development Goal (MDG) Target 7.C, which aimed to "halve, by 2015, the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation".[8] This has been replaced by the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), where Goal 6 aims to "ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all".[9] The JMP is now responsible for tracking progress toward those SDG 6 Targets focused on improving the standard of WASH services, including Target 6.1) "by 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all"; and Target 6.2) "by 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all, and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations".[10] In addition, the JMP collaborates with other organizations and agencies responsible for monitoring other WASH-related SDGs, including SDG Target 1.4 on improving access to basic services, SDG Target 3.9 on reducing deaths and illnesses from unsafe water, and SDG Target 4.a on building and upgrading adequate WASH services in schools.[10]

To establish a reference point from which progress toward achieving the SDGs could be monitored, the JMP produced "Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines".[5] According to this report, 2.1 billion people worldwide lack safe water at home, including 844 million people who do not have basic drinking water services.[5] Of those, 159 million people worldwide drink water directly from surface water sources, such as lakes and streams.[5] In addition, WHO estimates that, globally, 4.5 billion people do not have toilets at home that can safely manage waste despite improvements in access to sanitation over the past decades.[5][11] Approximately 600 million people share a toilet or latrine with other households and 892 million people practice open defecation.[5] Furthermore, only 1 in 4 people in low-income countries have handwashing facilities with soap and water at home; only 14% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa have handwashing facilities.[5] Worldwide, at least 500 million women and girls lack adequate, safe, and private facilities for managing menstrual hygiene.[12]

Access to WASH, in particular safe water, adequate sanitation, and proper hygiene education, can reduce illness and death, and also affect poverty reduction and socio-economic development. Lack of sanitation contributes to approximately 700,000 child deaths every year due to diarrhea. Chronic diarrhea can have a negative effect on child development (both physical and cognitive).[6] In addition, lack of WASH facilities can prevent students from attending school, impose a burden on women, and diminish productivity.[7]

The United Nation's International Year of Sanitation in 2008 helped to increase attention for funding of sanitation in WASH programs of many donors. For example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has increased their funding for sanitation projects since 2009, with a strong focus on reuse of excreta.[13]

Evidence regarding health outcomes

There is debate in the academic literature about the effectiveness on health outcomes when implementing WASH programs in low- and middle-income countries. Many studies provide poor quality evidence on the causal impact of WASH programs on health outcomes of interest. The nature of WASH interventions is such that high quality trials, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are expensive, difficult and in many cases not ethical. Causal impact from such studies are thus prone to being biased due to residual confounding. Blind studies of WASH interventions also pose ethical challenges and difficulties associated with implementing new technologies or behavioral changes without participant's knowledge.[14] Moreover, scholars suggest a need for longer-term studies of technology efficacy, greater analysis of sanitation interventions, and studies of combined effects from multiple interventions in order to more sufficiently gauge WASH health outcomes.[15]

Many scholars have attempted to summarize the evidence of WASH interventions from the limited number of high quality studies. Hygiene interventions, in particular those focusing on the promotion of handwashing, appear to be especially effective in reducing morbidity. A meta-analysis of the literature found that handwashing interventions reduced the relative risk of diarrhea by approximately 40%.[16][14] Similarly, handwashing promotion has been found to be associated with a 47% decrease in morbidity. However, a challenge with WASH behavioral intervention studies is an inability to ensure compliance with such interventions, especially when studies rely on self-reporting of disease rates. This prevents researchers from concluding a causal relationship between decreased morbidity and the intervention. For example, researchers may conclude that educating communities about handwashing is effective at reducing disease, but cannot conclude that handwashing reduces disease.[14] Point-of-use water supply and point-of-use water quality interventions also show similar effectiveness to handwashing, with those that include provision of safe storage containers demonstrating increased disease reduction in infants.[15]

Specific types of water quality improvement projects can have a protective effect on morbidity and mortality. A randomized control trial in India concluded that the provision of chlorine tablets for improving water quality led to a 75% decrease in incidences of cholera among the study population.[17] A quasi-randomized study on historical data from the United States also found that the introduction of clean water technologies in major cities was responsible for close to half the reduction in total mortality and over three-quarters of the reduction in infant mortality.[18] Distributing chlorine products, or other water disinfectants, for use in the home may reduce instances of diahorrea.[19] However, most studies on water quality improvement interventions suffer from residual confounding or poor adherence to the mechanism being studied. For instance, a study conducted in Nepal found that adherence to the use of chlorine tablets or chlorine solution to purify water was as low as 18.5% among program households.[17]

Studies on the effect of sanitation interventions on health are rare.[16] When studies do evaluate sanitation measures, they are mostly included as part of a package of different interventions.[14] A pooled analysis of the limited number of studies on sanitation interventions suggest that improving sanitation has a protective effect on health.[16] A UNICEF funded sanitation intervention (packaged into a broader WASH intervention) was also found to have a protective effect on under-five diarrhea incidence but not on household diarrhea incidence.[20]

WASH interventions appear to have some important unintended consequences as well. For instance, the UNICEF funded WASH intervention in Nigeria was perceived by many program beneficiaries as empowering women and youth.[20] In contrast, a study on a water well chlorination program in Guinea-Bissau in 2008 reported that families stopped treating water within their households because of the program which consequently increased their risk of cholera.[17]

Activities

Awareness raising

Awareness raising for the importance of WASH is regularly carried out by various organizations through their publications and activities on certain special days of the year (United Nations international observance days), namely: World Water Day for water (22 March), World Toilet Day for sanitation (19 November) and Global Handwashing Day for hygiene (15 October).

Neglected tropical diseases

Water, sanitation and hygiene interventions help to prevent many neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), for example soil-transmitted helminthiasis.[21] An integrated approach to NTDs and WASH benefits both sectors and the communities they are aiming to serve. This is especially true in areas that are endemic with more than one NTD.[21]

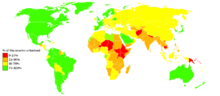

A map has been created to help identify areas with high levels of infection with the WASH-impacted NTDs and low levels of rural improved water and sanitation coverage.[22] In addition, WASH practitioners can use the manual "WASH and the Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Manual for WASH Implementers" to target, implement, and monitor WASH program impact on the NTDs.[23]

In August 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) unveiled a global strategy and action plan to integrate WASH with other public health interventions in order to accelerate elimination of NTDs.[24] The plan aims to intensify control or eliminate certain NTDs in specific regions by 2020.[25] It refers to the NTD roadmap milestones that included for example eradication of dracunculiasis by 2015 and of yaws by 2020, elimination of trachoma and lymphatic filariasis as public health problems by 2020, intensified control of dengue, schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiases.[26] The plan consists of four strategic objectives: improving awareness of benefits of joint WASH and NTD actions; monitoring WASH and NTD actions to track progress; strengthening evidence of how to deliver effective WASH interventions; and planning, delivering and evaluating WASH and NTD programmes with involvement of all stakeholders.[27] The aim is to use synergies between WASH and NTD programmes.

Challenges

Urban slums

.jpg)

Part of the reason for slow progress in sanitation may be due to the "urbanization of poverty", as poverty is increasingly concentrated in urban areas.[28] Migration to urban areas, resulting in denser clusters of poverty, poses a challenge for sanitation infrastructures that were not originally designed to serve so many households, if they existed at all.

As poverty becomes more concentrated in urban areas, one increasingly common phenomenon is the expansion of urban slums. Often built illegally in response to a lack of more permanent housing, slums have a specific set of problems associated with them. For instance, the lack of property rights and instability associated with a slum dwelling may mean that the resident would not be willing to invest in WASH services for a building that may not survive a storm, or from which she may be evicted. In addition, "New urban areas may be very heterogeneous—both ethnically and in terms of wealth distribution. They may face a constant influx of new migrants."[29] Such heterogeneity may make it difficult to coordinate efforts to build and maintain a shared sanitation system for slum neighborhoods.

For example, Oxfam is helping to provide 1 million liters of water each day in Mingkamen in South Sudan, but the demand is such that people must wait up to two hours in line to fill their containers. Sometimes fights break out at the water point because everyone is waiting so long.

Water distribution systems

Improper management of water distribution systems in developing nations can exacerbate the spread of water-borne diseases. The World Health Organization estimates that 25%-45% of water in distribution lines is lost through leaks in developing countries. These leaks can allow for contaminated water and pathogens to enter the distribution pipes, especially when power outages result in a loss of pressure in the water supply pipes. Cross-contamination of wastewater into potable water lines has resulted in major disease outbreaks, such as a Typhoid fever outbreak in Dushanbe, Tajikistan in 1997.[30]

WASH plans and monitoring

A World Health Organization report found that only one-third of the countries surveyed have national WASH plans that are being properly implemented, funded and regularly reviewed. In most countries monitoring was inconsistent and there were critical gaps. Reliable data is essential to inform policy decision, to monitoring and evaluate outcomes, and to identify those who do not have access to WASH. Many countries have WASH monitoring frameworks in place, but most of the data reported was inconsistent, weakening evaluation and outcome data analysis.[31]

In 1992, the United Nations proposed Integrated water resources management (IWRM) as a solution to WASH challenges and policy failures.[32] An integrated approach to water management aims to minimize challenges associated with water-borne disease, water justice, poor compliance with safe hygiene behaviors, and sustainability by involving stakeholders at every level of management and consumption. This approach also recognizes the political, economic, and social influence of WASH as well as the need to coordinate water and sanitation management.[33][34] Critics of current implementation of IWRM argue it has been externally imposed on developing countries and can be culturally inappropriate to the needs of individual communities. Instead, a hybrid approach that includes greater community-level management and flexibility but with the same goals as IWRM has been suggested.[32]

Failures of WASH systems

National government mapping and monitoring efforts, as well as post-project monitoring by NGOs or researchers, have identified the failure of water supply systems (including water points, wells and boreholes) and sanitation systems as major challenges. Many water and sanitation systems are unsustainable, failing to provide extended health benefits to communities in the long-term. This has been attributed to financial costs, inadequate technical training for operations and maintenance, poor use of new facilities and taught behaviors, and a lack of community participation and ownership.[35]

Access to WASH services also varies internally within nations depending on socio-economic status, political power, and level of urbanization. A 2004 estimate by UNICEF stated that urban households are 30% and 135% more likely to have access to improved water sources and sanitation respectively, as compared to rural areas. Moreover, the poorest populations cannot afford fees required for operation and maintenance of WASH infrastructure, preventing them from benefitting even when systems do exist.[30]

Schools

_(37720260454).jpg)

_(38403428742).jpg)

.jpg)

WASH in schools, sometimes called SWASH or WinS, significantly reduces hygiene-related disease, increases student attendance and contributes to dignity and gender equality.[36] WASH in schools contributes to healthy, safe and secure school environments that can protect children from health hazards, abuse and exclusion. It also enables children to become agents of change for improving water, sanitation and hygiene practices in their families and communities.

Data from over 10,000 schools in Zambia was analysed in 2017 and confirmed that improved sanitation provision in schools was correlated with high female-to-male enrolment ratios, and reduced repetition and drop-out ratios, especially for girls.[37] The study thus confirmed the linkages between adequate toilets in schools and educational progression of girls.[37]

More than half of all primary schools in the developing countries with available data do not have adequate water facilities and nearly two thirds lack adequate sanitation.[36] Even where facilities exist, they are often in poor condition.

Reasons for missing or poorly maintained water and sanitation facilities at schools in developing countries include lacking inter-sectoral collaboration; lacking cooperation between schools, communities and different levels of government; as well as a lack in leadership and accountability.[38]

Strong cultural taboos around menstruation, which are present in many societies, coupled with a lack of Menstrual Hygiene Management services in schools, results in girls staying away from school during menstruation.[39]

Approaches

Methods to improve the situation of WASH infrastructure at schools include on a policy level: broadening the focus of the education sector, establishing a systematic quality assurance system, distributing and using funds wisely.[38] Other practical recommendations include: have a clear and systematic mobilization strategy, support the education sector to strengthen intersectoral partnerships, establish a constant monitoring system which is located within the education sector, educate the educators and partner with the school management.[38]

Enabling environment

The support provided by development agencies to the government at national, state and district levels is helpful to gradually create what is commonly referred to as an enabling environment for WASH in schools. This includes sound policies, an appropriate and well-resourced strategy, and effective planning. Such efforts need to be sustained over longer time periods as ministries and departments of education are very large organizations, which generally show much inertia and are slow to reform.[40][41]

Success also hinges on local-level leadership and a genuine collective commitment of school stakeholders towards school development. Developing human and social capital amongst core school stakeholders is important. This applies to students and their representative clubs, headmaster and teachers, parents and SMC members. Furthermore, other stakeholders have to be engaged in their direct sphere of influence, such as: community members, community-based organizations, educations official, local authorities.[42][43]

Group handwashing

Supervised daily group handwashing in schools can be an effective strategy for building good hygiene habits, with the potential to lead to positive health and education outcomes for children.[44] This has for example been implemented in the "Essential Health Care Program" by the Department of Education in the Philippines.[45] Deworming twice a year, supplemented by washing hands daily with soap and brushing teeth daily with fluoride, is at the core of this national program. It has also been successfully implemented in Indonesia.[46][47]

Examples

UNICEF includes WASH initiatives in their work with schools in over 30 countries.[48]

Health facilities

The provision of adequate water, sanitation and hygiene is an essential part of providing basic health services in healthcare facilities. WASH in Health facilities aids in preventing the spread of infectious diseases as well as protects staff and patients. Urgent action is needed to improve WASH services in health facilities in developing countries.[49]

According to the World Health Organization, data from 54 countries in low and middle income settings representing 66,101 health facilities show that 38% of health care facilities lack improved water sources, 19% lack improved sanitation while 35% lack access to water and soap for handwashing. The absence of basic WASH amenities compromises the ability to provide routine services and hinders the ability to prevent and control infections. The provision of water in health facilities was the lowest in Africa, where 42% of healthcare facilities lack an improved source of water on-site or nearby. The provision of sanitation is lowest in the Americas with 43% of health care facilities lacking adequate services.[49]

The improvement of WASH standards within health facilities needs to be guided by national policies and standards as well as an allocated budget to improve and maintain services.[50] A number of solutions exist that can considerably improve the health and safety of both patients and service providers at health facilities.

- Availability of safe water: There is a need for improved water pump systems within health facilities. Provision of safe water is necessary for drinking but also for use in surgery and deliveries, food preparation, bathing and showering.[51]

- Improved handwashing practices among healthcare staff must be implemented through proper orientation and training. Functional hand washing stations at strategic points of care within the health facilities must be provided. In low resource settings, a sink or basin with water and soap or hand sanitizer need to be available at points of care and toilets.[51]

- Waste system management: Proper health care waste management and the safe disposal of excreta and waste water is crucial to preventing the spread of disease.[52] Waste should be safely separated within large bins in the consultation area and sharp objects and infectious wastes disposed of properly and safely.[51]

- Hygiene promotion: Clear and practical communication with patients and visitors, including staff, about hygiene promotion within the premises should be implemented.[52]

- Accessibility to toilets: Accessible and clean toilets, separated by gender, in sufficient numbers for staff, patients and visitors.[52] Improved sanitary facilities that are usable, separate for patients and staff, separate for women and allowing menstrual hygiene management, and meeting the needs of disabled people.[51]

History

The history of water supply and sanitation in general is the topic of a separate article.

Usage of the abbreviation "WASH"

The abbreviation WASH was used from the year 1988 onwards as an acronym for the "Water and Sanitation for Health" Project of the United States Agency for International Development.[53] At that time, the letter "H" stood for "health", not "hygiene". Similarly, in Zambia the term WASHE was used in a report in 1987 and stood for "Water Sanitation Health Education".[54] An even older USAID "WASH project report" dates back to as early as 1981.[55]

From about 2001 onwards, international organizations active in the area of water supply and sanitation advocacy, such as the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council and the International Water and Sanitation Centre (IRC) in the Netherlands began to use "WASH" as an umbrella term for water, sanitation and hygiene.[56] "WASH" has since then been broadly adopted as a handy acronym for water, sanitation and hygiene in the international development context.[57] The term "WatSan" was also used for a while, especially in the emergency response sector such as with IFRC and UNHCR,[58] but has not proven as popular as WASH.

WASH continues to be a development priority at the United Nations and UNICEF. One component of the Sustainable Development Goals is clean water and sanitation.[59] This includes several sub-components, including water quality, sanitation and hygiene, and access to drinking water. UNICEF's declared strategy is "to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all".[60]

Society and culture

Awards

Several prizes are awarded for individuals or organisations working on WASH, notably:

- The Stockholm Water Prize since 1991, with a wide-ranging view of water-related activities, along with the Stockholm Junior Water Prize and the Stockholm Industry Water Award.

- The University of Oklahoma International Water Prize since 2009, for WASH activities in developing countries.

- The Sarphati Sanitation Awards since 2013, for sanitation entrepreneurship.

See also

- History of water supply and sanitation

- Mass deworming

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- Sustainable Sanitation Alliance

- Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council

- Water access and gender

- Water issues in developing countries

- Water supply and women in developing countries

- Waterborne diseases

References

- "Goal 6 .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- Kooy, M. and Harris, D. (2012) Briefing paper: Political economy analysis for water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) service delivery. Overseas Development Institute

- "Key facts from JMP 2015 report". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- "WHO | Lack of sanitation for 2.4 billion people is undermining health improvements". www.who.int. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- Organization, World Health (2017). Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene : 2017 update and SDG baselines. World Health Organization,, UNICEF. Geneva. ISBN 978-9241512893. OCLC 1010983346.

- "Water, Sanitation & Hygiene: Strategy Overview". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: Introduction". UNICEF. UNICEF. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Goal 7: Ensure Environmental Sustainability". United Nations Millennium Development Goals website. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation". UNDP. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- United Nations (2015). Transforming our world the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development : A/RES/70/1. United Nations, Division for Sustainable Development. OCLC 973387855.

- UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking Water (2014). Investing in Water and Sanitation: Increasing Access, Reducing Inequalities (GLAAS 2014 Report). World Health Organization. p. iv. ISBN 978-92-4-150808-7. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "Menstrual Hygiene Management Enables Women and Girls to Reach Their Full Potential". World Bank. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- Elisabeth von Muench, Dorothee Spuhler, Trevor Surridge, Nelson Ekane, Kim Andersson, Emine Goekce Fidan, Arno Rosemarin (2013) Sustainable Sanitation Alliance members take a closer look at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s sanitation grants, Sustainable Sanitation Practice Journal, Issue 17, p. 4-10

- Cairncross, S; Hunt, C; Boisson, S; Bostoen, K; Curtis, V; Fung, I. C; Schmidt, W. P (2010). "Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea". International Journal of Epidemiology. 39: i193–205. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq035. PMC 2845874. PMID 20348121.

- Waddington, Hugh; Snilstveit, Birte; White, Howard; Fewtrell, Lorna (May 2012). "Water, sanitation and hygiene interventions to combat childhood diarrhoea in developing countries". Journal of Development Effectiveness. doi:10.23846/sr0017.

- Fewtrell, Lorna; Kaufmann, Rachel B; Kay, David; Enanoria, Wayne; Haller, Laurence; Colford, John M (2005). "Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 5 (1): 42–52. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01253-8. PMID 15620560.

- Taylor, Dawn L; Kahawita, Tanya M; Cairncross, Sandy; Ensink, Jeroen H. J (2015). "The Impact of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Interventions to Control Cholera: A Systematic Review". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0135676. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035676T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135676. PMC 4540465. PMID 26284367.

- Cutler, David M; Miller, Grant (2005). "The Role of Public Health Improvements in Health Advances: The Twentieth-Century United States". Demography. 42 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1353/dem.2005.0002. PMID 15782893.

- Clasen, Thomas F.; Alexander, Kelly T.; Sinclair, David; Boisson, Sophie; Peletz, Rachel; Chang, Howard H.; Majorin, Fiona; Cairncross, Sandy (2015-10-20), "Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea", The Cochrane Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10), pp. CD004794, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004794.pub3, PMC 4625648, PMID 26488938

- Toonen J, Akwataghibe N, Wolmarans L, Wegelin M. Evaluation of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) within the UNICEF Country Programme of Cooperation Final Report [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/Nigeria_Impact_Evaluation_of_WASH_within_the_UNICEF_Country_Programme_of_Cooperation_Report.pdf

- Johnston, E. Anna; Teague, Jordan; Graham, Jay P (2015). "Challenges and opportunities associated with neglected tropical disease and water, sanitation and hygiene intersectoral integration programs". BMC Public Health. 15: 547. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1838-7. PMC 4464235. PMID 26062691.

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases and WASH Index Map". Water, Sanitation & Hygiene for Neglected Tropical Disease Online Manual Resource. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "WASH&NTD Manual". Water, Sanitation & Hygiene for Neglected Tropical Diseases. WASH NTD. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "WHO strengthens focus on water, sanitation and hygiene to accelerate elimination of neglected tropical diseases". World Health Organization (WHO). 27 August 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2015): Water Sanitation and Hygiene for accelerating and sustaining progress on Neglected Tropical Diseases. A global strategy 2015 - 2020. Geneva, Switzerland, p. 26.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2012). Accelerating work to overcome the global impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases. A raodmap for implementation. Geneva, Switzerland.

- "Poster on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) for accelerating and sustaining progress on NTDs" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). 27 August 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- Programme, United Nations Human Settlements (2003). Facing the slum challenge : global report on human settlements, 2003 (PDF) (Repr. ed.). London: Earthscan Publications. p. xxvi. ISBN 978-1-84407-037-4. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- Duflo, Esther; Galiani, Sebastian; Mobarak, Mushfiq (October 2012). Improving Access to Urban Services for the Poor: Open Issues and a Framework for a Future Research Agenda (PDF). Cambridge, MA: Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab. p. 5. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- Moe, Christine L.; Rheingans, Richard D. (July 2006). "Global challenges in water, sanitation and health" (PDF). Journal of Water and Health. 4 (S1): 41–57. doi:10.2166/wh.2006.0043. ISSN 1477-8920.

- "UN reveals major gaps in water and sanitation – especially in rural areas". WHO. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Butterworth, John (2010). "Finding practical approaches to integrated water resources management". Water Alternatives. 3 (1): 68–81.

- Tilley, Elizabeth; Strande, Linda; Lüthi, Christoph; Mosler, Hans-Joachim; Udert, Kai M.; Gebauer, Heiko; Hering, Janet G. (2014-09-02). "Looking beyond Technology: An Integrated Approach to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Low Income Countries". Environmental Science & Technology. 48 (17): 9965–9970. Bibcode:2014EnST...48.9965T. doi:10.1021/es501645d. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 25025776.

- Dreibelbis, Robert; Winch, Peter J; Leontsini, Elli; Hulland, Kristyna RS; Ram, Pavani K; Unicomb, Leanne; Luby, Stephen P (December 2013). "The Integrated Behavioural Model for Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: a systematic review of behavioural models and a framework for designing and evaluating behaviour change interventions in infrastructure-restricted settings". BMC Public Health. 13 (1): 1015. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1015. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 4231350. PMID 24160869.

- Carter, R. C.; Tyrrel, S. F.; Howsam, P. (August 1999). "The Impact and Sustainability of Community Water Supply and Sanitation Programmes in Developing Countries". Water and Environment Journal. 13 (4): 292–296. doi:10.1111/j.1747-6593.1999.tb01050.x. ISSN 1747-6585.

- United Nations Children's Fund, Raising Even More Clean Hands: Advancing Learning, Health and Participation through WASH in Schools, New York: UNICEF, 2012

- Agol, Dorice; Harvey, Peter; Maíllo, Javier (2018-03-01). "Sanitation and water supply in schools and girls' educational progression in Zambia". Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development. 8 (1): 53–61. doi:10.2166/washdev.2017.032. ISSN 2043-9083.

- Dauenhauer, K., Schlenk, J., Langkau, T. (2016). Managing WASH in Schools: Is the Education Sector Ready? - A Thematic Discussion Series hosted by GIZ and SuSanA. Sustainable Sanitation Alliance, Germany

- UNESCO (2014). "Puberty Education and Menstrual Hygiene Management" (PDF). UNESCO.

- Tiberghien, Jacques-Edouard (2016). School WASH research: India country report. http://www.wateraid.org/what-we-do/our-approach/research-and-publications/view-publication?id=8851e0b6-7a36-4102-8630-4555130e750d: WaterAid.

- Tiberghien, Jacques-Edouard (2016). School WASH research: Pakistan country report. http://www.wateraid.org/what-we-do/our-approach/research-and-publications/view-publication?id=8851e0b6-7a36-4102-8630-4555130e750d: WaterAid.

- Tiberghien, Jacques-Edouard (2016). School WASH research: Nepal country report. http://www.wateraid.org/what-we-do/our-approach/research-and-publications/view-publication?id=8851e0b6-7a36-4102-8630-4555130e750d: WaterAid.

- Tiberghien, Jacques-Edouard (2016). School WASH research: Bangladesh country report. http://www.wateraid.org/what-we-do/our-approach/research-and-publications/view-publication?id=8851e0b6-7a36-4102-8630-4555130e750d: WaterAid.

- UNICEF, GIZ (2016). Scaling up group handwashing in schools - Compendium of group washing facilities across the globe. New York, USA; Eschborn, Germany

- UNICEF (2012) Raising Even More Clean Hands: Advancing Health, Learning and Equity through WASH in Schools, Joint Call to Action

- School Community Manual - Indonesia (formerly Manual for teachers), Fit for School. GIZ Fit for School, Philippines. 2014. ISBN 978-3-95645-250-5.

- GIZ Fit for School. Field Guide: Hardware for Group Handwashing in Schools. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Philippines. ISBN 978-3-95645-057-0.

- "Water, sanitation and education | Water, Sanitation and Hygiene | UNICEF".

- Water, sanitation and hygiene in health care facilities World Health Organization(2015) http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/wash-health-care-facilities/en/ Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in health care facilities Joint action for universal access and improved quality of care. World Health Organization (WHO) https://www.washinhcf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/23-WASH_Health_SectorCollaboration_Oct2015.pdf Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Monitoring WASH in Health Care Facilities. World Health Organization(2016). http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/monitoring/coverage/wash-in-hcf-core-questions.pdf?ua=1 Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Water, sanitation and hygiene in health care facilities in Asia and the Pacific. WaterAid (2015).http://www.wateraidamerica.org/publications/water-sanitation-and-hygiene-in-health-care-facilities-in-asia-pacific Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "WASH Technical Report No 37" (PDF). USAID. 1988. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- WASHE (Water Sanitation Health Education) in Zambia (1987). Participatory health education: ready for use materials: design and production WASHE programme. WASHE Western Province, Zambia. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- WASH Technical Report No 7 (1981). Facilitation of community organization: an approach to water and sanitation programs in developing countries (WASH Task No 94): prepared for USAID. USAID/WASH Washington DC, USA. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Jong, D. de (2003) Advocacy for water, environmental sanitation and hygiene - Thematic overview paper, IRC, The Netherlands

- "Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion" (PDF). WHO.int. 2005. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- UNHCR Division of Operational Services (2008). A Guidance for UNHCR Field Operations on Water and Sanitation Services. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goal #6, accessed online at http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-and-sanitation/ on October 3, 2017

- UNICEF Strategy for Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene 2016-2030, accessible online at https://www.unicef.org/wash/files/UNICEF_Strategy_for_WASH_2016-2030.pdf