About Teen Pregnancy

Teen Pregnancy in the United States

In 2015, a total of 229,715 babies were born to women aged 15–19 years, for a birth rate of 22.3 per 1,000 women in this age group. This is another record low for U.S. teens and a drop of 8% from 2014. Birth rates fell 9% for women aged 15–17 years and 7% for women aged 18–19 years.1

Although reasons for the declines are not totally clear, evidence suggests these declines are due to more teens abstaining from sexual activity, and more teens who are sexually active using birth control than in previous years.2,3

Still, the U.S. teen pregnancy rate is substantially higher than in other western industrialized nations4, and racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in teen birth rates persist.5

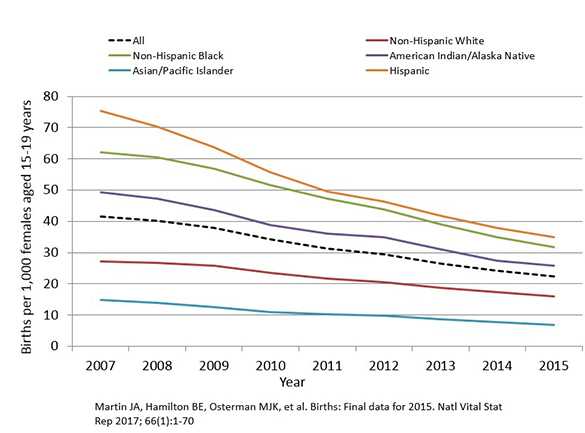

Births per 1,000 Females Aged 15–19 Years, by Race and Hispanic Ethnicity, 2007-2015

Disparities in Teen Birth Rates

Teen birth rates declined from 2014 to 2015 for all races and for Hispanics. Among 15- to 19-year-olds, teen birth rates decreased:

- 10% for Asian/Pacific Islanders

- 9% for non-Hispanic blacks

- 8% for Hispanics

- 8% for non-Hispanic whites

- 6% for American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/AN)1

In 2015, the birth rate of Hispanic teens were still more than two times higher than the rate for non-Hispanic white teens. The birth rate of non-Hispanic black teens was almost twice as high as the rate among non-Hispanic white teens, and American Indian/Alaska Native teen birth rates remained more than one and a half times higher than the non-Hispanic white teen birth rate.1 Geographic differences in teen birth rates persist, both within and across states. Among some states with low overall teen birth rates, some counties have high teen birth rates.5

Less favorable socioeconomic conditions, such as low education and low income levels of a teen’s family, may contribute to high teen birth rates.6Teens in child welfare systems are at higher risk of teen pregnancy and birth than other groups. For example, young women living in foster care are more than twice as likely to become pregnant than those not in foster care.7

To improve the life opportunities of adolescents facing significant health disparities and to have the greatest impact on overall U.S. teen birth rates, CDC uses data to inform and direct interventions and resources to areas with the greatest need.

The Importance of Prevention

Teen pregnancy and childbearing bring substantial social and economic costs through immediate and long-term impacts on teen parents and their children.

- In 2010, teen pregnancy and childbirth accounted for at least $9.4 billion in costs to U.S. taxpayers for increased health care and foster care, increased incarceration rates among children of teen parents, and lost tax revenue because of lower educational attainment and income among teen mothers.8

- Pregnancy and birth are significant contributors to high school dropout rates among girls. Only about 50% of teen mothers receive a high school diploma by 22 years of age, whereas approximately 90% of women who do not give birth during adolescence graduate from high school.9

- The children of teenage mothers are more likely to have lower school achievement and to drop out of high school, have more health problems, be incarcerated at some time during adolescence, give birth as a teenager, and face unemployment as a young adult.10

These effects continue for the teen mother and her child even after adjusting for those factors that increased the teenager’s risk for pregnancy, such as growing up in poverty, having parents with low levels of education, growing up in a single-parent family, and having poor performance in school.10

CDC Priority: Reducing Teen Pregnancy and Promoting Health Equity Among Youth

Teen pregnancy prevention is one of CDC’s top seven priorities, a “winnable battle” in public health, and of paramount importance to health and quality of life for our youth. CDC supports the implementation of evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs that have been shown, in at least one program evaluation, to have a positive effect on preventing teen pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, or sexual risk behaviors. Evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs have been identified by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) TPP Evidence Review, which used a systematic process for reviewing evaluation studies against a rigorous standard. Currently, the Evidence Review covers a variety of diverse programs, including sexuality education programs, youth development programs, abstinence education programs, clinic-based programs, and programs specifically designed for diverse populations and settings. In addition to evidence-based prevention programs, teens need access to youth-friendly contraceptive and reproductive health services and support from parents and other trusted adults, who can play an important role in helping teens make healthy choices about relationships, sex, and birth control. Efforts at the community level that address social and economic factors associated with teen pregnancy also play a critical role in addressing racial/ethnic and geographical disparities observed in teen births in the US.

Citations

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: Final data for 2015. National vital statistics report; vol 66, no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

- Santelli J, Lindberg L, Finer L, Singh S. Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: the contribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive use. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):150-6.

- Lindberg LD, Santelli JS, Desai, S. Understanding the Decline in Adolescent Fertility in the United States, 2007–2012. J Adolesc Health. 2016: 1-7

- Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, Eilers MA, Singh S. Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):223-30.

- Reduced Disparities in Birth Rates Among Teens Aged 15–19 Years — United States, 2006–2007 and 2013–2014, MMWR 2016

- Penman-Aguilar A, Carter M, Snead MC, Kourtis AP. Socioeconomic disadvantage as a social determinant of teen childbearing in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(suppl 1):5-22.

- Boonstra HD. Teen pregnancy among women in foster care: a primer. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2011; 14(2).

- National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, Counting It Up: The Public Costs of Teen Childbearing 2013. Accessed March 31, 2016.

- Perper K, Peterson K, Manlove J. Diploma Attainment Among Teen Mothers. Child Trends, Fact Sheet Publication #2010-01: Washington, DC: Child Trends; 2010.

- Hoffman SD. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2008.

- Page last reviewed: May 4, 2017

- Page last updated: May 9, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir