Social Determinants and Eliminating Disparities in Teen Pregnancy

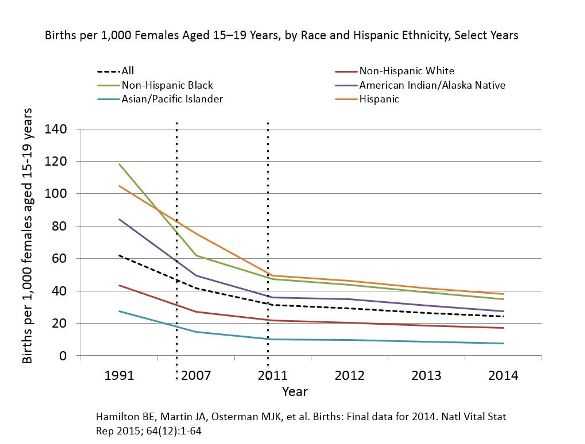

U.S. teen birth rates (births per 1,000 15–19-year-old females) decreased 9% overall from 2013 (26.5) to 2014 (24.2).1 Decreases occurred for teens of all races and for Hispanic teens. Despite these declines, racial/ethnic, geographic, and socioeconomic disparities persist. Achieving health equity, eliminating disparities, and improving the health of all groups is an overarching goal of Healthy People 2020. Evidence-based programs and clinical services to prevent teen pregnancy through individual behavior change are important, but research is also shedding light on the role social determinants of health play in the overall distribution of disease and health, including teen pregnancy.

Disparities by Race and Ethnicity

From 2013–2014, teen birth rates decreased 12% for American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/AN), 11% for non-Hispanic blacks and Asian/Pacific Islanders, 9% for Hispanics, and 7% for non-Hispanic whites.1 However, in 2014, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic teen birth rates were still more than two times higher than the rate for non-Hispanic white teens, and American Indian/Alaska Native teen birth rates remained more than one and a half times higher than the non-Hispanic white teen birth rate.

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health are conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. (Healthy People 2020). Certain social determinants, such as high unemployment, low education, and low income, have been associated with higher teen birth rates. Interventions that address socioeconomic conditions like these can play a critical role in addressing disparities observed in U.S. teen birth rates.

Health Equity

Health equity is achieved when everyone has an equal opportunity to reach his or her health potential regardless of social position or other characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual identity, or disability. Health inequities are closely linked with social determinants of health.

Geographic Disparities

- Although teen birth rates (births per 1,000 females aged 15-19) declined in 43 states and Washington, DC, between 2013 and 2014, geographic disparities persist, with state-specific 2014 teen birth rates ranging from 10.6 in Massachusetts to 39.5 in Arkansas.1

- Across counties, teen birth rates vary greatly:

- Higher-rate counties are clustered in the South and Southwest, but high-rate counties also occur in states with low overall birth rates.2

- Teen birth rates are higher in rural counties than in urban centers and suburban counties, regardless of race/ethnicity. In 2010, the teen birth rate in rural counties was nearly one-third higher than the rest of the country (43 versus 33 births per 1,000 females aged 15-19 years). 3

- From 1990 to 2010, the birth rate among teens in rural counties declined only 32%, compared to the decline in urban centers (49%) and in suburban counties (40%) during the same period. 3

Socioeconomic Disparities

- Socioeconomic conditions in communities and families may contribute to high teen birth rates. Examples of these factors include—

- Low education and low income levels of a teen's family. 4

- Few opportunities in a teen's community for positive youth involvement. 4

- Neighborhood racial segregation. 4

- Neighborhood physical disorder (graffiti, abandoned vehicles, litter, alcohol containers, cigarette butts, glass on the ground). 4

- Neighborhood-level income inequality. 4

- Teens in child welfare systems are at increased risk of teen pregnancy and birth than other groups. For example, young women living in foster care are more than twice as likely to become pregnant than those not in foster care. 5

Taking Action to Eliminate Disparities and Address Social Determinants of Teen Pregnancy

Eliminating disparities in teen pregnancy and birth rates would—

- Help achieve health equity.

- Improve the life opportunities and health outcomes of young people.

- Reduce the economic costs of teen childbearing.

Efforts that focus on social determinants of health in teen pregnancy prevention efforts, particularly at the community level, play a critical role in addressing racial/ethnic and geographical disparities observed in teen births in the US.

CDC is supporting three organizations from 2015-2020 to enhance youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in publicly funded health centers and increase the number of young people accessing sexual and reproductive health services. A key focus is working to refer and link vulnerable young people to these services—including those in foster care, juvenile justice and probation, or housing developments. The three organizations funded to conduct this work are Sexual Health Initiative for Teens North Carolina (Durham, NC), Mississippi First, Inc. (Coahoma, Quitman, and Tunica counties, MS), and the Georgia Association for Primary Health Care, Inc. (Chatham County, GA).

The Office of Adolescent Health (OAH) and CDC are partnering to fund the evaluation of innovative interventions designed for young men aged 15-24 years old to reduce their risk of fathering a teen pregnancy. Interventions focus on young men at high risk of fathering a teen pregnancy, such as young men at risk of health disparities due to low socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, or exposure to other social determinants negatively affecting health. The organizations funded to conduct this work are Columbia University, New York University, and Promundo.

As part of the President's Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative, CDC partnered with OAH and the Office of Population Affairs from 2010-2015 to fund nine state- and community-based organizations and five national organizations to implement community-wide initiatives to reduce teenage pregnancy and address disparities in teen pregnancy and birth rates. Addressing social determinants of teen pregnancy was a central tenet of each initiative. For tools and resources related to addressing social determinants of teen pregnancy, please visit: http://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/prevent-teen-pregnancy/diverse-communities.html. Examples of this work from the nine state- and community-based organizations include:

- Analyzing community-level data to identify specific social determinants associated with teen pregnancy in Mobile County.

- Training program staff, youth leadership team, and community partners on the social determinants of health and teen pregnancy.

- Engaging faith-based leaders in teen pregnancy prevention and partnering with Richmond County Juvenile Court and Kids Restart, Inc., to implement evidence-based programs with youth in detention and in the child welfare system.

- Using Connecticut’s Health Equity Index—a community-based assessment tool for identifying social, political, economic, and environmental conditions associated with specific health outcomes—to highlight the associations between teen pregnancy and select social determinants (e.g., low unemployment rates, high rates of poverty).

- Using the data to inform the selection of program and clinical partners located in communities most in need of teen pregnancy prevention efforts.

- Partnering with Capital Workforce Partners to improve youth employment opportunities and enhance knowledge and skill sets in various areas, including reproductive health, among youth aged 14–17 years.

- Hosting “Community Conversations for Action” sessions with community members and leaders in Holyoke and Springfield to determine their roles in reducing teen pregnancy among Latinos, faith communities, court-involved youth, foster youth, and homeless youth.

- Partnering with the TLC: Building Healthy Relationships Program to implement ¡Cuidate! with young Latino males involved with the Massachusetts Department of Youth Services/Department of Children and Families.

- Addressing teen pregnancy specifically among urban, lower income, underrepresented racial and ethnic groups in the South Bronx.

- Raising public awareness in Gaston County of the link between teen pregnancy and social determinants of health through documentaries and presentations to community groups; reaching youth of color and males with evidence-based programs; and partnering with faith institutions on teen pregnancy prevention.

- Improving the provision of high-quality evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs for underserved populations by training youth-serving organizations to work with underserved populations; holding focus groups with underserved populations to identify factors affecting teen pregnancy; and partnering with organizations to implement evidence-based programs with detained/incarcerated youth, males, youth in foster care, West African immigrant youth, and pregnant and parenting teens.

- Working with Bexar County Juvenile Probation youth; foster care youth in the Baptist Children and Family Services and St. PJ's Children's Home; out-of-school teen parents in the Adult Detention Center; pregnant and parenting teens through the Nurse Family Partnership and Children's Shelter iParent; and pregnant and parenting teen coordinators in schools.

- Partnering with Spartanburg County Department of Social Services to improve counseling of foster youth on reproductive health, referring youth for clinical services as appropriate, and educating foster parents on teen pregnancy prevention.

- Examining social determinants of teen pregnancy specific to the Spartanburg community, such as by engaging Spartanburg Youth Action Board members in a Reproductive Justice Timeline activity to examine how being a member of a minority group may affect access to reproductive health services and decision making.

Resources from CDC and other public health entities for addressing social determinants of health

- CDC. Reduced Disparities in Birth Rates Among Teens Aged 15–19 Years — United States, 2006–2007 and 2013–2014, MMWR 2016

- Public Health Reports: Socioeconomic disadvantage as a social determinant of teen childbearing in the U.S. [PDF - 483KB]

- CDC: Promoting Health Equity: A Resource to Help Communities Address Social Determinants of Health [PDF - 392KB]

- CDC: Healthy Communities Program: supports eliminating socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health disparities as an integral part of its chronic disease prevention and health promotion efforts. To improve health on the local, state, and national level, communities are encouraged to identify and address social determinants of health and improve these conditions through environmental changes.

- CDC: Social Determinants of Health

- Healthy People 2020: Social Determinants of Health

- World Health Organization: Social Determinants of Health

- Reproductive Health Equity for Youth: Information, tools and resources to address social determinants and disparities in teen pregnancy (from national partner John Snow, Inc./JSI Research & Training Institute)

- Public health Reports: Applying Social Determinants of Health to Public Health Practice

- CDC NCHHSTP White Paper: Establishing a Holistic Framework to Reduce Inequities in HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STDs, and Tuberculosis in the United States [PDF - 304KB]

- CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas: Social Determinants of Health Slides

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: A New Way to Talk about the Social Determinants of Health

Sources

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: Final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2015; 64(12):1-64.

- CDC. Reduced Disparities in Birth Rates Among Teens Aged 15–19 Years — United States, 2006–2007 and 2013–2014. MMWR 2016.

- The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Teen childbearing in rural America. Science Says. 2013;47.

- Penman-Aguilar A, Carter M, Snead MC, Kourtis AP. Socioeconomic disadvantage as a social determinant of teen childbearing in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(suppl 1):5-22.

- Boonstra HD. Teen pregnancy among women in foster care: a primer. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2011;14(2).

- Page last reviewed: August 8, 2016

- Page last updated: April 29, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir