For Healthcare Professionals

Although poliovirus is no longer endemic in the United States, it’s important that healthcare professionals rule out poliovirus infection in cases of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) that are clinically compatible with polio, particularly those with anterior myelitis, to ensure that any importation of poliovirus is quickly identified and investigated.

The Virus

Poliovirus is a member of the enterovirus subgroup, family Picornaviridae. The virus causes polio, or poliomyelitis, which is a highly infectious disease.

Poliovirus infections only occur in humans. Poliovirus is spread by the fecal-oral and respiratory routes. Infection is more common in infants and young children. Polio occurs at an earlier age among children living in poor hygienic conditions. In temperate climates,

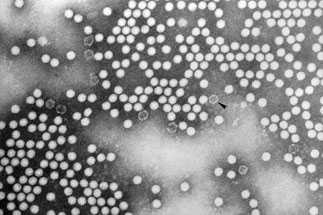

Transmission electron micrograph of poliovirus type 1

Most people infected with poliovirus (72%) will not have any visible symptoms. About 1 out of 4 people (24%) will have flu-like symptoms. These symptoms usually last 2 to 5 days then go away on their own.

About 1 out of 100 people will have weakness or paralysis in their arms, legs, or both. The paralysis can lead to permanent disability and death. About 2 to 10 people out of 100 who have paralysis from polio die because the virus affects the muscles that help them breathe.

The incubation period of nonparalytic poliomyelitis is 3 to 6 days. For the onset of paralysis in paralytic poliomyelitis, the incubation period usually is 7 to 21 days.

Adults who had paralytic poliomyelitis during childhood may develop noninfectious post-polio syndrome 15 to 40 years later. Post-polio syndrome is characterized by slow and irreversible exacerbation of weakness often in those muscle groups involved during the original infection. Muscle and joint pain also are common manifestations. The prevalence and incidence of post-polio syndrome is unclear. Studies estimate that 25% to 40% of polio survivors suffer from post-polio syndrome.

Background

Polio was once considered one of the most feared diseases in the United States. In the early 1950s, before polio vaccines were available, polio outbreaks were reported to cause more than 15,000 cases of paralysis each year in the United States. Following introduction of vaccines in 1955 and 1963 the number of polio cases fell rapidly to less than 100 in the 1960s and fewer than 10 in the 1970s. There has not been a case of wild-type polio acquired in the United States since 1979. The last imported case of wild-type polio was in 1993. However, polio is still a threat in other parts of the world and could easily be brought into the United States from countries where wild-type poliovirus is circulating. In 2015, eight countries reported cases of polio: Afghanistan, Equatorial Guinea, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Madagascar, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Ukraine. In the last decade, at least 40 polio-free countries have been affected through international travel.

There is always the possibility that polio could be imported (brought into the country by a traveler) into the United States. That’s why it is important to exclude poliovirus infection in clinically compatible, unexplained cases of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), particularly those with anterior myelitis, to ensure that any case of poliomyelitis is quickly identified and investigated. See MMWR for more information.

2014-2016 Reports of Acute Flaccid Myelitis (AFM)

From August to December, 2014, CDC verified reports of 120 children in 34 states who developed acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that met CDC’s outbreak case definition (onset of acute limb weakness on or after August 1, 2014, and a magnetic resonance image showing a spinal cord lesion largely restricted to gray matter in a patient age <21 years). Passive surveillance for AFM has continued at CDC since 2014. From January through June, 2016, CDC received an increased number of reports of suspected AFM compared to the same period in 2015.

To date, no single pathogen has been consistently detected in CSF, respiratory specimens, stool, or blood at either CDC or state laboratories. Clinicians are encouraged to maintain vigilance for cases of AFM among all age groups and to report suspected cases of AFM to CDC. Reporting of cases will help states and CDC monitor the occurrence of this illness and better understand factors possibly associated with AFM. For more information on AFM cases, see AFM Surveillance.

Diagnosis and Laboratory Testing

AFP is the manifestation of a wide spectrum of clinical diseases and is not nationally notifiable in the United States. Worldwide, children younger than 15 years of age are the age group at highest risk of developing polio and some other forms of AFP. Even in the absence of laboratory-documented poliovirus infection, AFP is expected to occur at a rate of at least 1 per 100,000 children annually. It can result from a variety of infectious and noninfectious causes. Known viral causes of AFP include enterovirus, adenovirus and West Nile virus. However, AFP caused by these agents is very uncommon in the United States. A study examining AFP in 245 children younger than 15 years of age in California from 1992-1998 found the most common diagnoses were Guillain-Barré Syndrome (23%), unspecified AFP (21%), and botulism (12%).

Consider polio in patients who have unexplained AFP. A probable case of polio is defined as an acute onset of flaccid paralysis of one or more limbs with decreased or absent tendon reflexes in the affected limbs, without other apparent cause, and without sensory or cognitive loss. Paralysis usually begins in the arm or leg on one side of the body (asymmetric) and then moves towards the end of the arm or leg (progresses to involve distal muscle groups). This is described as descending paralysis. Many patients with AFP will have a lumbar puncture and analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) performed as part of their evaluation. Detection of poliovirus in CSF from confirmed polio cases is uncommon, and a negative CSF test result cannot be used to rule out polio.

Consider polio in patients with polio-like symptoms, especially if the person is unvaccinated and recently traveled abroad to a place where polio still occurs, or was exposed to a person who recently traveled from one of these areas.

If you suspect polio:

- Promptly isolate the patient to avoid disease transmission.

- Immediately report the suspected case to the health department. A confirmed paralytic poliomyelitis case needs to be reported to CDC within 4 hours of meeting notification criteria.

- Obtain specimens for diagnostic testing for poliovirus detection (polymerase chain reaction), viral isolation and intratypic differentiation as early in the course of illness as possible, including 2 stool specimens and 2 throat swab specimens at least 24 hours apart, ideally within 14 days of symptom onset.

The rapid investigation of suspected polio cases is critical to identifying possible poliovirus transmission and implementing proper control measures. Rapid investigation allows specimens for poliovirus isolation to be gathered to confirm whether a case of paralytic polio is the result of wild or vaccine-related poliovirus infection. For more information see CDC poliomyelitis guidelines for epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory investigations of AFP to rule out poliovirus infection.

Also see MMWR, Acute Flaccid Paralysis with Anterior Myelitis — California, June 2012–June 2014.

Reporting Suspected Cases of Polio

Each state and territory has regulations or laws governing the reporting of diseases and conditions of public health importance. These regulations and laws list the diseases to be reported and describe those persons or groups responsible for reporting, such as health-care providers, hospitals, laboratories, schools, daycare and childcare facilities, and other institutions. Contact your state health department for reporting requirements in your state.

Paralytic polio has been classified as “Immediately notifiable, Extremely Urgent” which requires that local and state health departments contact CDC within 4 hours.

Reports of non-paralytic polio are designated as “Immediately notifiable, Urgent” which requires notification of the CDC within 24 hours.

CDC (Emergency Operations Center, 770-488-7100) will provide consultation regarding the collection of appropriate clinical specimens for virus isolation and serology, the initiation of appropriate consultations and procedures to rule out or confirm poliomyelitis, the compilation of medical records, and most importantly, the evaluation of the likelihood that the disease may be caused by wild poliovirus.

For more information about what should be collected as part of a case investigation see:

- Poliomyelitis section of the Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

- Suspected Polio Case Worksheet [3 pages]

Each state and territory has regulations or laws governing the reporting of diseases and conditions of public health importance. Contact your state health department for reporting requirements in your state.

Polio Vaccination

Polio vaccine provides the best protection against polio. Visit the following pages for specific vaccination recommendations.

For guidance on temporary polio vaccine recommendations for travelers, see this 6-minute video with CDC’s Dr. Mark Pallansch.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance to US Clinicians Regarding New WHO Polio Vaccination Requirements for Travel by Residents of and Long-term Visitors to Countries with Active Polio Transmission. June 2, 2014.

- Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Progress toward eradication of polio–worldwide, January 2011-March 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(17):335-8.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ed. Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; April, 2013

- Zangwill KM, Yeh SH, Wong EJ, Marcy SM, Eriksen E, Huff KR, et al. Paralytic syndromes in children: epidemiology and relationship to vaccination. Pediatr Neurol. 2010;42(3):206-12.

- Page last reviewed: June 21, 2016

- Page last updated: August 22, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir