Chapter 12: Poliomyelitis

Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

Printer friendly version [9 pages]

Authors: Gregory S Wallace, MD, MS, MPH; M. Steven Oberste, PhD

Disease description

Poliomyelitis is a highly contagious disease caused by three serotypes of poliovirus. Infection with poliovirus results in a spectrum of clinical manifestations from inapparent infection to nonspecific febrile illness, aseptic meningitis, paralytic disease, and death. Two phases of acute poliomyelitis can be distinguished: a nonspecific febrile illness (minor illness) followed, in a small proportion of patients, by aseptic meningitis and/or paralytic disease (major illness). The ratio of cases of inapparent infection to paralytic disease among susceptible individuals ranges from 100:1 to 1000:1 or more.

Following poliovirus exposure, viral replication occurs in the oropharynx and the intestinal tract. Viremia follows, which may result in infection of central nervous system cells. The virus attaches and enters cells via a specific poliovirus receptor. Replication of poliovirus in motor neurons of the anterior horn and brain stem results in cell destruction and causes the typical clinical manifestations of poliomyelitis. Depending on the site of infection and paralysis, poliomyelitis can be classified as spinal, bulbar, or spino-bulbar disease. Progression to maximum paralysis is rapid (2-4 days), usually associated with fever and muscle pain, and rarely progresses after the temperature has returned to normal. Spinal paralysis is typically asymmetric, more severe proximally than distally, and deep tendon reflexes are absent or diminished. Bulbar paralysis may compromise respiration and swallowing. Between 2%-10% of cases of paralytic poliomyelitis are fatal. Infection with poliovirus results in lifelong, type-specific immunity.

Following the acute episode, many patients recover muscle functions at least partially, and prognosis for recovery can usually be established within six months after onset of paralytic manifestations.

Background

Poliomyelitis became an epidemic disease in the United States (U.S.) at the turn of the 20th century. Epidemics of ever-increasing magnitude occurred, with more than 20,000 cases of poliomyelitis with permanent paralysis reported in 1952. Following the introduction of effective vaccines, first inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) in 1955, and oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) starting in 1961, the reported incidence of poliomyelitis in the U.S. declined dramatically to <100 cases in 1965 and to <10 cases in 1973. With the introduction and widespread use of OPV (containing live attenuated poliovirus strains), vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) was recognized. By 1973, for the first time in the U.S., more cases of vaccine-associated disease were reported than paralytic disease caused by wild poliovirus.[1] This trend continued, and in 1997 the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended changing to a sequential polio immunization schedule that included two doses of IPV, followed by two doses of OPV.[2] VAPP occurred less frequently under this schedule, and in 2000, this recommendation was updated to a schedule of all IPV.[3, 4, 5] OPV is no longer manufactured or available in the United States.

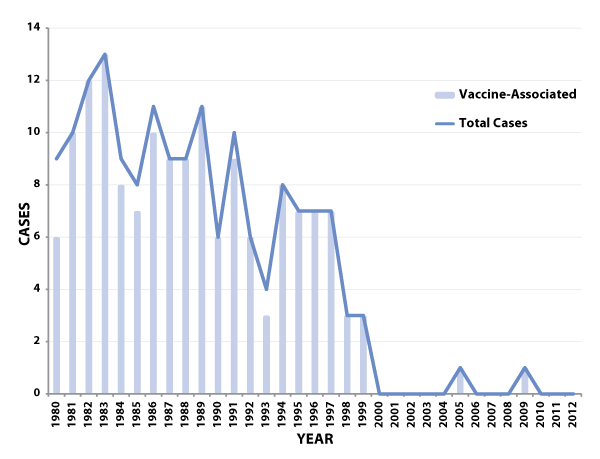

The last U.S. cases of indigenously transmitted wild poliovirus disease were reported in 1979. Since 1986, with the exception of one imported wild-type poliomyelitis case in 1993, all reported cases of paralytic poliomyelitis in the United States have been vaccine-associated (see Figure 1).[6, 7] VAPP was a very rare disease, with an average of eight reported cases annually during 1980-1999, or one case reported for every 2.4 million doses of OPV distributed.[6, 7] The risk of VAPP is highest following the first dose of OPV and among immunodeficient persons. Since changing to an all-IPV immunization schedule in 2000, there have been only two cases of VAPP reported in the U.S., one in an imported case and one in a genetically immunocompromised person who was most likely exposed to OPV before it use was discontinued.

Figure 1: Total number of reported paralytic poliomyelitis cases (including imported cases) and number of reported vaccine-associated cases—United States, 1980-2012

Following the successful implementation of the polio eradication initiative in the Americas beginning in 1985, the last case of wild poliovirus-associated disease was detected in Peru in 1991. The hemisphere was certified as free of indigenous wild poliovirus in 1994.[8] In 1988, the World Health Assembly adopted the goal of worldwide eradication of poliomyelitis by the year 2000.[9] By 2001, substantial progress toward eradication had been reported: a more than 99% decrease in the number of reported cases of poliomyelitis was achieved. Wild poliovirus remains endemic in just three countries: Afghanistan and Pakistan in Asia, and Nigeria in Africa.[10, 11, 12] Due to the successful implementation of the global poliomyelitis eradication initiative, the risk of importation of wild poliovirus into the U.S. decreased substantially over the last decade. Nevertheless, the potential for importation of wild poliovirus into the United States remains until worldwide poliomyelitis eradication is achieved. Find more information on the status of poliomyelitis eradication.

Because inapparent infection with OPV or wild virus strains no longer contributes to establishing or maintaining poliovirus immunity in the U.S., universal vaccination of infants and children is the only means of establishing and maintaining population immunity against poliovirus to prevent poliomyelitis cases and epidemics caused by importation of wild virus into the U.S. Population-based surveys have confirmed that the prevalence of poliovirus antibodies among school-age children, adolescents, and young adults in the United States is high (>90% to poliovirus types 1 and 2, and >85% to type 3).[13, 14] In addition, seroprevalence surveys conducted in two inner-city areas of the United States (areas in which routine coverage was low) during 1990-1991 found that >80% of all children 12-47 months of age had antibodies to all three poliovirus serotypes.[15] Data from 1997-1998 also demonstrate a high seroprevalence of antibody to all poliovirus serotypes among children aged 19-35 months who lived in the inner-city areas of four cities in the U.S., with 96.8%, 99.8%, and 94.5% seropositive to poliovirus types 1, 2, and 3, respectively.[16] However, members of certain religious groups objecting to vaccination have remained susceptible to poliomyelitis. These groups appear to be at highest risk for epidemic poliomyelitis. The last two outbreaks of poliomyelitis in the U.S. were reported among religious groups—in 1972 among Christian Scientists[17] and in 1979 among the Amish.[1] Clustering of other sub-populations that object to vaccination can also occur, which could increase the susceptibility to vaccine-preventable diseases, including polio.[18]

The emergence of circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs) causing an outbreak of poliomyelitis was first reported in Hispaniola in 2000.[19] One or more cVDPV outbreaks have been reported each year since.[20] These outbreaks have occurred in regions where OPV is being used and overall routine polio vaccination rates are low. The vaccine polioviruses are able to replicate in the intestinal tract of inadequately immunized persons, and may be transmitted to others with inadequate immunity. During these multiple infections, the viruses may regain some of the properties of wild polioviruses, such as transmissibility and neurovirulence. Clinical disease caused by these VDPVs is indistinguishable from that caused by wild polioviruses. Outbreak control measures in these outbreaks have relied upon vaccination with OPV.

A circulating VDPV has also been identified in an under-vaccinated Amish community in the U.S. in 2005.[21]

Importance of rapid identification

Rapid investigation of suspected poliomyelitis cases is critical to identifying possible wild poliovirus transmission. Rapid detection of wild or virus-related cases permits the timely implementation of controls to limit the spread of imported wild poliovirus or cVDPVs and maintain the eradication of wild poliovirus in the U.S. Moreover, rapid investigation of suspected cases will allow collection of specimens for poliovirus isolation, which is critical for confirming whether a case of paralytic poliomyelitis is the result of wild or vaccine-related virus infection.

Importance of surveillance

The poliomyelitis surveillance system serves to

- detect importation of wild poliovirus into the U.S. and

- detect the presence of vaccine-derived poliovirus in the U.S.

Disease reduction goals

No cases of paralytic polio due to indigenously acquired wild poliovirus have been reported in the U.S. since 1979. There have been two reported cases of VAPP in the U.S. since 2000 when the use of OPV was discontinued. High coverage with poliovirus vaccine is required to maintain elimination of poliomyelitis in the United States until global eradication is achieved.

Case definition

Poliomyelitis, Paralytic

The following case definition for paralytic poliomyelitis has been approved by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), and was published in 2010.[22]

Case classification

Probable: Acute onset of a flaccid paralysis of one or more limbs with decreased or absent tendon reflexes in the affected limbs, without other apparent cause, and without sensory or cognitive loss.

Confirmed: Acute onset of a flaccid paralysis of one or more limbs with decreased or absent tendon reflexes in the affected limbs, without other apparent cause, and without sensory or cognitive loss; AND in which the patient

- has a neurologic deficit 60 days after onset of initial symptoms, or

- has died, or

- has unknown follow-up status.

Comment: All suspected cases of paralytic poliomyelitis are reviewed by a panel of expert consultants before final classification occurs. Confirmed cases are then further classified based on epidemiologic and laboratory criteria.[23] Only confirmed cases are included in Table 1 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Suspected cases under investigation are enumerated in a footnote to the MMWR table.

Poliovirus infection, non-paralytic

The following case definition for non-paralytic poliovirus infection has been approved by CSTE, and was published in 2010.[24]

Case classification

Confirmed: Any person without symptoms of paralytic poliomyelitis in whom a poliovirus isolate was identified in an appropriate clinical specimen, with confirmatory typing and sequencing performed by the CDC Poliovirus laboratory, as needed.

Laboratory testing

Laboratory studies, especially attempted poliovirus isolation, are critical for confirming whether a case of paralytic poliomyelitis is the result of wild or vaccine-related virus infection. For additional information on laboratory testing, see Chapter 22, "Laboratory Support for Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases."

Virus isolation

The likelihood of poliovirus isolation is highest from stool specimens, intermediate from pharyngeal swabs, and low from blood or spinal fluid. The isolation of poliovirus from stool specimens contributes to the diagnostic evaluation but does not constitute proof of a causal association of such viruses with paralytic poliomyelitis.[1] Isolation of virus from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is diagnostic but is rarely accomplished. Because virus shedding can be intermittent and to increase the probability of poliovirus isolation, at least two stool specimens and two throat swabs should be obtained 24 hours apart from patients with suspected poliomyelitis as early in the course of the disease as possible (i.e., immediately after poliomyelitis is considered as a possible differential diagnosis), and ideally within the first 14 days after onset of paralytic disease. Specimens should be sent to the state or other reference laboratories for primary isolation on appropriate cell lines. Laboratories should forward virus isolates to CDC for intratypic differentiation and possible sequencing to determine whether the poliovirus isolate is wild or vaccine-related.

To increase the probability of poliovirus isolation, at least two stool specimens should be obtained 24 hours apart from patients with suspected poliomyelitis as early in the course of disease as possible (ideally within 14 days after onset).

Isolation of wild poliovirus constitutes a public health emergency and appropriate control efforts must be initiated immediately (in consultation among health-care providers, the state and local health departments, and CDC).

Serologic testing

Serology may be helpful in supporting the diagnosis of paralytic poliomyelitis. An acute serum specimen should be obtained as early in the course of disease as possible, and a convalescent specimen should be obtained at least three weeks later. A four-fold neutralizing antibody titer rise between the acute and convalescent specimens suggests poliovirus infection. Nondetectable antibody titers in both specimens may help support the rule out of poliomyelitis but may also be falsely negative in immunocompromised persons, who are also at highest risk for paralytic poliomyelitis. In addition, neutralizing antibodies appear early and may be at high levels by the time the patient is hospitalized; thus, a four-fold rise may not be demonstrated. Vaccinated individuals would also be expected to have measurable titers; therefore vaccination history is important for serology interpretation. Polio serology is subject to several limitations, including the inability to differentiate between antibody induced by immunization from antibody induced by infection and to distinguish between antibody induced by vaccine-related poliovirus and antibody induced by wild virus. Serologic assays to detect antipoliovirus antibodies are available in some commercial and state public health laboratories, and CDC.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

The cerebrospinal fluid usually contains an increased number of leukocytes—from 10 to 200 cells/mm3 (primarily lymphocytes) and a mildly elevated protein, from 40 to 50 mg/100 ml. These findings are nonspecific and may result from a variety of infectious and noninfectious conditions. Detection of poliovirus in CSF is very uncommon.

Reporting

Each state and territory has regulations or laws governing the reporting of diseases and conditions of public health importance.[25] These regulations and laws list the diseases to be reported and describe those persons or groups responsible for reporting, such as health-care providers, hospitals, laboratories, schools, daycare and childcare facilities, and other institutions. Contact your state health department for reporting requirements in your state.

Reporting to CDC

Because poliomyelitis has been eliminated from the Americas, each reported case of suspected poliomyelitis should be followed up by local and state health departments in close collaboration with CDC. Paralytic polio has been classified as “Immediately notifiable, Extremely Urgent“ which requires that local and state health departments contact CDC within 4 hours. Reports of non-paralytic polio are designated as “Immediately notifiable, Urgent” which requires notification of the CDC within 24 hours. CDC (Emergency Operations Center, 770-488-7100) will provide consultation regarding the collection of appropriate clinical specimens for virus isolation and serology, the initiation of appropriate consultations and procedures to rule out or confirm poliomyelitis, the compilation of medical records, and most importantly, the evaluation of the likelihood that the disease may be caused by wild poliovirus.

Information to collect

Demographic, clinical, and epidemiologic information are collected to:

- Determine whether the suspected case meets the case definition for paralytic poliomyelitis

- Determine whether the disease may be caused by wild poliovirus

The following data elements are epidemiologically important and should be collected in the course of a case investigation. See Appendix 14 [3 pages] for details on each data category. Additional information may be collected at the direction of the state health department or CDC.

- Demographic information

- Name

- Address

- Date of birth

- Age

- Sex

- Ethnicity

- Race

- Country of birth

- Length of time resident in U.S.

- Reporting source

- County

- Earliest date reported

- Clinical

- Hospitalizations: dates and duration of stay

- Date of onset of symptoms

- Complications

- Immunologic status of case-patient

- Outcome (case survived or died)

- Date of death

- Postmortem examination results

- Death certificate diagnoses

- Laboratory and clinical testing

- Serologic test

- Stool test

- Throat swab test

- EMG

- MRI

- Vaccine information

- Dates and types of polio vaccination

- Number of doses of polio vaccine received

- Manufacturer of vaccine

- Vaccine lot number

- If not vaccinated, reason

- Epidemiological

- Recent travel to polio-endemic areas or OPV using countries

- Contact with persons recently returning form polio-endemic areas or OPV using countries

- Contact with recent OPV recipient

- Setting (Is case-patient a member of a group objecting to vaccination?)

Travel history

Because the last cases of paralytic poliomyelitis due to indigenously acquired wild poliovirus infection in the U.S. were reported in 1979, it is likely that wild poliovirus in a suspected case-patient is imported, either by the suspected patient directly or by a contact of the case-patient. Results of virus isolation and differentiation may not be available at the time of the case investigation. Therefore, to rule out the possibility of imported wild poliovirus, a detailed travel history of suspected cases and of other household and nonhousehold contacts should be obtained. Any history of contacts with visitors, especially those from polio-endemic areas, might be particularly revealing.

Setting

Because the last two outbreaks of poliomyelitis in the United States were reported among Christian Scientists in 1972[17] and the Amish in 1979,[1] a suspected case of poliomyelitis reported from a group objecting to vaccination should be assigned the highest priority for follow-up and collection of specimens. VDPVs also pose a risk of poliomyelitis in communities with low vaccination coverage. In addition, isolation of wild poliovirus from residents of Canada in 1993[26] and 1996[27] demonstrates the potential for wild poliovirus importation into this continent. The strain isolated in Canada in 1993 was linked epidemiologically and by genomic sequencing to the 1992 poliomyelitis outbreak in the Netherlands, and the 1996 isolate was from a child who had recently visited India.

Vaccination

All children should receive four doses of IPV given at 2 months, 4 months, 6-18 months, and 4-6 years of age. In addition, because of potential confusion in using different vaccine products for routine and catch-up immunization, recommendations for poliovirus vaccination were updated in 2009.[28] ACIP recommends the following:

- The 4-dose IPV series should continue to be administered at ages 2 months, 4 months, 6-18 months, and 4-6 years.

- The final dose in the IPV series should be administered at age ≥4 years regardless of the number of previous doses.

- The minimum interval from dose 3 to dose 4 is extended from 4 weeks to 6 months.

- The minimum interval from dose 1 to dose 2, and from dose 2 to dose 3, remains 4 weeks.

- The minimum age for dose 1 remains age 6 weeks.

ACIP also updated its recommendation concerning the use of minimum age and minimum intervals for children in the first six months of life. Use of the minimum age and minimum intervals for vaccine administration in the first six months of life are recommended only if the vaccine recipient is at risk for imminent exposure to circulating poliovirus (e.g., during an outbreak or because of travel to a polio-endemic region). ACIP made this precaution because shorter intervals and earlier start dates lead to lower seroconversion rates.

In addition, ACIP is clarifying the poliovirus vaccination schedule to be used for specific combination vaccines. When DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel) is used to provide four doses at ages 2, 4, 6, and 15-18 months, an additional booster dose of age-appropriate IPV-containing vaccine (IPV [Ipol] or DTaP-IPV [Kinrix]) should be administered at age 4-6 years. This will result in a 5-dose IPV vaccine series, which is considered acceptable by ACIP. DTaP-IPV/Hib is not indicated for the booster dose at age 4-6 years. ACIP recommends that the minimum interval from dose 4 to dose 5 should be at least 6 months to provide an optimum booster response. In accordance with existing recommendations, if a child misses an IPV dose at age 4-6 years, the child should receive a booster dose as soon as feasible.

Enhancing surveillance

A number of activities can improve the detection and reporting of cases and improve the comprehensiveness and quality of reporting. Additional surveillance activities are listed in Chapter 19, "Enhancing Surveillance."

Promoting awareness

Because of the severity of poliomyelitis disease, clinicians are often the first to suspect the diagnosis of poliomyelitis and they are the key to timely reporting of suspected cases. However, disease reporting by clinicians is often delayed because it is only after other differential diagnoses are ruled out that the diagnosis of poliomyelitis is considered. Efforts should be made to promote physicians’ awareness of the importance of prompt reporting of suspected cases to the state and local health department and the CDC, and the need to obtain stool and throat specimens early in the disease course.

Ensuring laboratory capabilities

Make sure that the state laboratory or other easily accessible laboratory facility is capable of performing, at a minimum, primary virus isolation on appropriate cell lines. The CDC polio laboratory is always available for consultation and/or testing.

Obtaining laboratory confirmation

Appropriate stool and throat specimens (two specimens taken at least 24 hours apart during the first 14 days after onset of paralytic disease) should be collected.

Active surveillance

Active surveillance should be conducted for every confirmed case of poliomyelitis to assure timely reporting. The diagnosis of a case of poliomyelitis, particularly in a member of a group that refuses vaccination (such as the Amish or Christian Scientists), should prompt immediate control measures as well as active surveillance activities. These activities should include active contact tracing among populations at risk.

Case investigation

Guidelines and a worksheet for the investigation of suspected cases of poliomyelitis are included as Appendix 14 [3 pages]. Suspected cases of poliomyelitis should be reported immediately to the state health department. CDC Emergency Operations Center should be contacted at 770-488-7100. Timely collection of stool specimens is important in establishing the diagnosis and determining appropriate control measures, in the event of wild poliovirus isolation (see “Virus isolation” in “Laboratory testing”).

References

- Strebel PM, Sutter RW, Cochi SL, et al. Epidemiology of poliomyelitis in the United States one decade after the last reported case of indigenous wild virus-associated disease. Clin Infect Dis 1992;14:568-79.

- CDC. Poliomyelitis prevention in the United States: Introduction of a sequential vaccination schedule of inactivated poliovirus vaccine followed by oral poliovirus vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 1997;46(RR-3):1-25.

- CDC. Poliomyelitis prevention in the United States: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2000;49(No. RR-5):1-22.

- CDC. Recommended childhood immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years - United States, 2010. MMWR 2010;58:1-4.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases.Prevention of poliomyelitis: recommendations for use of only inactivated poliovirus vaccine for routine immunization. Pediatrics 1999;104:1404-6.

- CDC. Paralytic poliomyelitis - United States, 1980-1994. MMWR 1997;46:79-83.

- Prevots DR, Sutter RW, Strebel PM, et al. Completeness of reporting for paralytic polio, United States, 1980-1991. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1994;148:479-85.

- CDC. Certification of poliomyelitis elimination - the Americas, 1994. MMWR 1994;43:720-2.

- World Health Assembly. Global eradication of poliomyelitis by the year 2000. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1988; resolution no. 41.28.

- CDC. Tracking progress toward global polio eradication - Worldwide, 2009-2010. MMWR 2011;60(14):441-5.

- CDC. Progress toward interruption of wild poliovirus transmission - Worldwide, January 2010-March 2011. MMWR 2011;60(18):582-6.

- CDC. Progress toward global poliomyelitis eradication - Africa, 2011. MMWR 2012;61(11):190-4.

- Kelley PW, Petruccelli BP, Stehr-Green P, et al. The susceptibility of young adult Americans to vaccine-preventable infections. A national serosurvey of US army recruits. JAMA 1991;266:2724-9.

- Orenstein WA, Wassilak SGF, Deforest A, et al. Seroprevalence of polio virus antibodies among Massachusetts schoolchildren. In: Program and Abstracts of the 28th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (abstract no. 512). Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology.

- Chen RT, Hausinger S, Dajani A, et al. Seroprevalence of antibody against poliovirus in inner-city preschool children: Implications for vaccination policy in the United States. JAMA 1996:275:1639-45.

- Prevots R, Pallansch MW, Angellili M, et al. Seroprevalence of poliovirus antibodies among low SES children aged 19-35 months in 4 cities, United States, 1997-1998. Presented at the 39th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, CA, Sep. 26-29. Abstract 158.

- Foote FM, Kraus G, Andrews MD, et al. Polio outbreak in a private school. Conn Med 1973:37:643-4.

- Smith PJ, Chu SY, Barker LE. Children who have received no vaccines: Who are they and where do they live? Pediatrics 2004;114:187-195.

- CDC. Update: Outbreak of poliomyelitis- Dominican Republic and Haiti, 2000-2001. MMWR 2001;50:855-6.

- Modlin JF. The bumpy road to polio eradication. NEJM 2010;362(25):2346-49.

- Alexander JP, Ehresmann K, Seward J, et al. Transmission of imported vaccine-derived poliovirus in an undervaccinated community in Minnesota. JID 2009;199:391-7.

- CSTE Positon Statement Number: 09-ID-53. (Poliomyelitis, paralytic)

- Sutter RW, Brink EW, Cochi SL, et al. A new epidemiologic and laboratory classification system for paralytic poliomyelitis cases. Am J Pub Health 1989;79:495-8.

- CSTE Position Statement Number: 09-ID-53. (Poliovirus infection, nonparalytic)

- Roush S, Birkhead G, Koo D, et al. Mandatory reporting of diseases and conditions by health care professionals and laboratories. JAMA 1999;282:164-70.

- CDC. Isolation of wild poliovirus type 2 among members of a religious community objecting to vaccination - Alberta, Canada, 1993. MMWR 1993;42:337-9.

- Ministry of Health, Ontario. Wild type poliovirus isolated in Hamilton. Public Health and Epidemiology Report, Ontario 1996;7:51-2.

- CDC. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) regarding routine poliovirus vaccinaton. MMWR 2009;58:829-30.

- Page last reviewed: April 1, 2014

- Page last updated: April 1, 2014

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir