Pathogen & Environment

For more information on the appearance of Naegleria fowleri, visit the Photos page.

Naegleria fowleri is a heat-loving (thermophilic), free-living ameba (single-celled microbe), commonly found around the world in warm fresh water (like lakes, rivers, and hot springs) and soil 1, 2. Naegleria fowleri is the only species of Naegleria known to infect people. Most of the time, Naegleria fowleri lives in freshwater habitats by feeding on bacteria. However, in rare instances, the ameba can infect humans by entering the nose during water-related activities. Once in the nose, the ameba travels to the brain and causes a severe brain infection called primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is usually fatal 1-3.

History

The first PAM infections were reported in 1965 in Australia. The ameba identified caused a fatal infection in 1961 and turned out to be a new species that has since been named Naegleria fowleri after one of the original authors of the report, M. Fowler 1. The first infections in the U.S., which occurred in 1962 in Florida 2, were reported soon after. Subsequent investigations in Virginia using archived autopsy tissue samples identified PAM infections that had occurred in Virginia as early as 1937 3.

References

- Fowler M, Carter RF. Acute pyogenic meningitis probably due to Acanthamoeba sp.: a preliminary report. [PDF – 4 pages] Br Med J. 1965;2:740-2.

- Butt CG. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:1473-6.

- SN Gustavo. Fatal primary amebic meningoencephalitis. A retrospective study in Richmond, Virginia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970;54:737-42.

Life Cycle

Naegleria fowleri has 3 stages in its life cycle: cyst  , trophozoite

, trophozoite  , and flagellate

, and flagellate  . The only infective stage of the ameba is the trophozoite. Trophozoites are 10-35 µm long with a granular appearance and a single nucleus. The trophozoites replicate by binary division during which the nuclear membrane remains intact (a process called promitosis)

. The only infective stage of the ameba is the trophozoite. Trophozoites are 10-35 µm long with a granular appearance and a single nucleus. The trophozoites replicate by binary division during which the nuclear membrane remains intact (a process called promitosis)  . Trophozoites infect humans or animals by penetrating the nasal tissue

. Trophozoites infect humans or animals by penetrating the nasal tissue  and migrating to the brain

and migrating to the brain  via the olfactory nerves causing primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).

via the olfactory nerves causing primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).

Cyst stage.

Trophozoite stage.

Flagellated stage.

Trophozoites can turn into a temporary, non-feeding, flagellated stage (10-16 µm in length) when stimulated by adverse environmental changes such as a reduced food source. They revert back to the trophozoite stage when favorable conditions return 1. Naegleria fowleri trophozoites are found in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and tissue, while flagellated forms are occasionally found in CSF. Cysts are not seen in brain tissue. If the environment is not conducive to continued feeding and growth (like cold temperatures, food becomes scarce) the ameba or flagellate will form a cyst. The cyst form is spherical and about 7-15 µm in diameter. It has a smooth, single-layered wall with a single nucleus. Cysts are environmentally resistant in order to increase the chances of survival until better environmental conditions occur 2.

References

- Visvesvara G, Yoder J, Beach MJ. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis Chapter 73. 2012. p. 442-7. In: Netter’s Infectious Diseases, Eds. Yong EC, Stevens DL. Elsevier Saunders. Philadelphia, PA.

- Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50(1):1-26.

Environmental Conditions Affecting Survival

Naegleria fowleri is normally found in the natural environment and is well adapted to surviving in various habitats, particularly warm-water environments. Although the trophozoite stage is relatively sensitive to environmental changes, the cysts are more environmentally hardy. There are no means yet known that would control natural Naegleria fowleri levels in lakes and rivers.

Drying: Drying appears to make trophozoites nonviable instantaneously and cysts nonviable in <5 min 1.

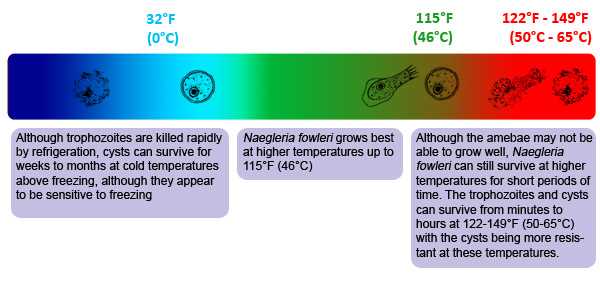

Temperature: Naegleria fowleri is a heat-loving (thermophilic) ameba able to grow and survive at higher temperatures, such as those found in hot springs and in the human body, even under fever temperatures. Naegleria fowleri grows best at higher temperatures up to 115°F (46°C) 2. Although the amebae may not be able to grow well, Naegleria fowleri can still survive at higher temperatures for short periods of time. The trophozoites and cysts can survive from minutes to hours at 122-149°F (50-65°C) with the cysts being more resistant at these temperatures 1, 3. Although trophozoites are killed rapidly by refrigeration, cysts can survive for weeks to months at cold temperatures above freezing, although they appear to be sensitive to freezing 1, 3. As a result, colder temperatures are likely to cause Naegleria fowleri to encyst in lake and river sediment where the cyst offers more protection from freezing water temperatures.

Disinfection: Naegleria fowleri trophozoites and the more resistant cysts are sensitive to disinfectants like chlorine 1, 3-7 and monochloramine 7, 8. Chlorine is the most common disinfectant used to treat drinking water and swimming pools. The chlorine sensitivity of Naegleria fowleri is moderate and in the same range as the cysts from Giardia intestinalis, another waterborne pathogen 9, 10. The inactivation data for Naegleria is limited but recent CT values (concentration of disinfectant [mg/l] X contact time [in minutes]) have been developed 6. Under laboratory conditions, chlorine at a concentration of 1 ppm (1 mg/L) added to 104.4°F (38°C) clear (non-turbid) well water at a pH of 8.01 will reduce the number of viable and more resistant Naegleria fowleri cysts by 99.99% (4 logs) in 56 minutes (CT of 56) 6. Cloudy (turbid) water requires longer disinfection times or higher concentrations of disinfectant.

Salinity: Naegleria fowleri does not survive in sea water and has not been detected in sea water 1, 3.

References

- Chang SL. Resistance of pathogenic Naegleria to some common physical and chemical agents. [PDF – 8 pages] Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:368-75.

- Griffin JL. Temperature tolerance of pathogenic and nonpathogenic free-living amoebas. Science.1972;178(63):869-70.

- Tiewcharoen S, Junnu V. Factors affecting the viability of pathogenic Naegleria species isolated from Thai patients. J Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;22:15-21.

- De Jonckheere J, van de Voorde H. Differences in destruction of cysts of pathogenic and nonpathogenic Naegleria and Acanthamoeba by chlorine. [PDF – 4 pages] Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976;31:294-7. (1mg/l for an hour for cysts)

- Cursons RT, Brown TJ, Keys EA. Effect of disinfectants on pathogenic free-living amoebae: in axenic conditions. [PDF – 5 pages] Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40:62-6.

- Sarkar P, Gerba C. Inactivation of Naegleria fowleri by chlorine and ultraviolet light. J AWWA. 2012;104:51-2.

- Robinson BS, Christy PE. Disinfection of water for control of amoebae. Water. 1984;11:21-4.

- Ercken D, Verelst L, Declerck P, Duvivier L, Van Damme A, Ollevier F. Effects of peracetic acid and monochloramine on the inactivation of Naegleria lovaniensis. Water Sci Technol. 2003;47(3):167-71.

- Jarroll EL, Bingham AK, Meyer EA. Effect of chlorine on Giardia lamblia cyst viability. [PDF – 5 pages] Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:483-7.

- Rice EW, Hoff JC, Schaefer FW 3rd. Inactivation of Giardia cysts by chlorine. [PDF – 2 pages] Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:250-1.

Environmental Testing

In general, CDC does not recommend testing rivers and lakes for Naegleria fowleri because the ameba is naturally occurring and there is no established relationship between detection or concentration of Naegleria fowleri and risk of infection. Environmental testing may be warranted for investigations in which Naegleria fowleri detection may be useful for establishing geographical distribution in new environments 1, survival in disinfected water bodies, or in household water systems 2.

References

- Kemble SK, Lynfield R, DeVries AS, Drehner DM, Pomputius WF 3rd, Beach MJ, Visvesvara GS, da Silva AJ, Hill VR, Yoder JS, Xiao L, Smith KE, Danila R. Fatal Naegleria fowleri infection acquired in Minnesota: possible expanded range of a deadly thermophilic organism. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:805-9.

- Yoder JS, Straif-Bourgeois S, Roy SL, Moore TA, Visvesvara GS, Ratard RC, Hill V, Wilson JD, Linscott AJ, Crager R, Kozak NA, Sriram R, Narayanan J, Mull B, Kahler AM, Schneeberger C, da Silva AJ, Beach MJ. Deaths from Naegleria fowleri associated with sinus irrigation with tap water: a review of the changing epidemiology of primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;1-7.

References

- Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. The immune response to Naegleria fowleri amebae and pathogenesis of infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51:243-59.

- Visvesvara GS. Free-living amebae as opportunistic agents of human disease. J Neuroparasitol. 2010;1.

- Yoder JS, Eddy BA, Visvesvara GS, Capewell L, Beach MJ. The epidemiology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the USA, 1962-2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:968-75.

- Page last reviewed: February 28, 2017

- Page last updated: February 28, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir