Sources of Infection & Risk Factors

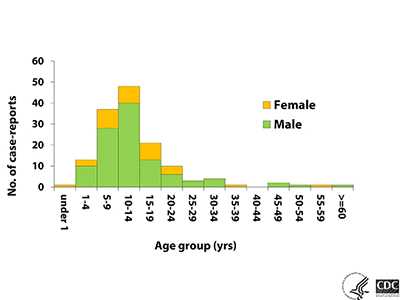

Naegleria fowleri is a free-living ameba that causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a disease of the central nervous system 1, 2. PAM is a rare disease* that is almost always fatal. In the United States**, there have been 143 PAM infections from 1962 through 2016 with only four survivors. These infections have primarily occurred in 15 southern-tier states, with more than half of all infections occurring in Texas and Florida. PAM also disproportionately affects males and children. The reason for this distribution pattern is unclear but may reflect the types of water activities (such as diving or watersports) that might be more common among young boys 3.

Where Naegleria fowleri is Found

Naegleria fowleri is a heat-loving (thermophilic) ameba found around the world 1, 2. Naegleria fowleri grows best at higher temperatures up to 115°F (46°C; see Pathogen and Environment page) and can survive for short periods at higher temperatures 3, 4. Naegleria fowleri is naturally found in warm freshwater environments such as lakes and rivers 5-9, naturally hot (geothermal) water such as hot springs 10, warm water discharge from industrial or power plants 11, 12, geothermal well water 13, 14, poorly maintained or minimally chlorinated swimming pools 15, water heaters 16, and soil 5, where it lives by feeding on bacteria and other microbes in the environment. Sampling of lakes in the southern tier of the U.S. indicates that Naegleria fowleri is commonly present in many southern tier lakes in the U.S. during the summer 5-9 but infections have also recently occurred in northern states 17. Naegleria is not found in salt water, like the ocean.

References

- Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. The immune response to Naegleria fowleri amebae and pathogenesis of infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol.2007;51:243-59.

- Visvesvara GS. Free-living amebae as opportunistic agents of human disease. J Neuroparasitol. 2010;1.

- Griffin JL. Temperature tolerance of pathogenic and nonpathogenic free-living amoebas. Science. 1972;178(4063):869-70.

- Chang SL. Resistance of pathogenic Naegleria to some common physical and chemical agents. [PDF – 8 pages] Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:368-75.

- Maclean RC, Richardson DJ, LePardo R, Marciano-Cabral F. The identification of Naegleria fowleri from water and soil samples by nested PCR. Parasitol Res. 2004;93(3):211–17.

- Wellings FM, Amuso PT, Chang SL, Lewis AL. Isolation and identification of pathogenic Naegleria from Florida lakes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;34:661–7.

- John DT, Howard MJ. Seasonal distribution of pathogenic free-living amebae in Oklahoma waters. Parasitol Res. 1995;81(3):193–201.

- Duma RJ. Study of pathogenic free-living amebas in fresh-water lakes in Virginia. EPA Publication. 1980;EPA-PB-126369, Summary, 1981 is EPA-600/S1-80-037.

- Ettinger MR, Webb SR, Harris SA, McIninch SP, C Garman G, Brown BL. Distribution of free-living amoebae in James River, Virginia, USA. Parasitol Res. 2003;89(1):6-15.

- Sheehan KB, Fagg JA, Ferris MJ, Henson JM. PCR detection and analysis of the free-living amoeba Naegleria in hot springs in Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:5914-8.

- Sykora JK, Keleti G, Martinez AJ. Occurrence and pathogenicity of Naegleria fowleri in artificially heated waters. Appl Envion Microbiol. 1983;45(3):974-9.

- Stevens AR, Tyndall RL, Coutant CC, Willaert E. Isolation of the etiological agent of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis from artificially heated waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;34(6):701-5.

- Marciano-Cabral F, MacLean R, Mensah A, LaPat-Polasko L. Identification of Naegleria fowleri in domestic water sources by nested PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(10):5864-9.

- Blair B, Sarkar P, Bright KR, Marciano-Cabral F, Gerba CP. Naegleria fowleri in well water. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(9):1499-501.

- Yoder JS, Eddy BA, Visvesvara GS, Capewell L, Beach MJ. The epidemiology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the USA, 1962-2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(7):968-75.

- Yoder JS, Straif-Bourgeois S, Roy SL, Moore TA, Visvesvara GS, Ratard RC, Hill V, Wilson JD, Linscott AJ, Crager R, Kozak NA, Sriram R, Narayanan J, Mull B, Kahler AM, Schneeberger C, da Silva AJ, Beach MJ. Deaths from Naegleria fowleri associated with sinus irrigation with tap water: a review of the changing epidemiology of primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;1-7.

- Kemble SK, Lynfield R, DeVries AS, Drehner DM, Pomputius WF 3rd, Beach MJ, Visvesvara GS, da Silva AJ, Hill VR, Yoder JS, Xiao L, Smith KE, Danila R. Fatal Naegleria fowleri infection acquired in Minnesota: possible expanded range of a deadly thermophilic organism. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:805-9.

Where PAM Infections Have Occurred

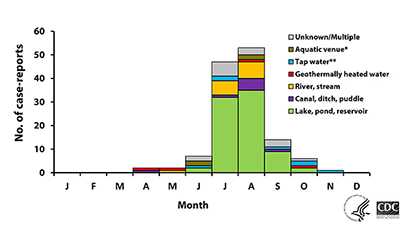

PAM infections have been reported from around the world 1, 2. Infections have primarily occurred in southern-tier states in the U.S. 3, but infections were documented in Minnesota in 2010 and 2012 4 and other northern states since that time. Over half of all reported infections have occurred in Florida and Texas. In the United States and the rest of the world, PAM is primarily spread via swimming in warm freshwater lakes and rivers (about 3 out of 4 U.S. infections from 1962-2016) 3. Other recreational water types like hot springs and canals have also been linked to PAM infections 3.

Six infections in the U.S. have been associated with using water from drinking water systems to swim 5 or use a slip-n-slide 6, immerse the head in a bathtub 5, mix solutions for nasal irrigation using a neti pot 7, or perform ritual nasal rinsing or ablution 8. PAM infections also occurred in the 1970s and 1980s in Australia 9, 10 that were linked to showering, swimming, or having other nasal exposure to contaminated drinking water. The infections were linked to piping drinking water overland, sometimes for hundreds of kilometers, that resulted in the water being heated and having low to zero disinfectant levels that resulted in the water and pipes becoming colonized by Naegleria fowleri. Several water systems in the states of Western Australia and South Australia continue to monitor regularly for Naegleria fowleri colonization in drinking water distribution systems 11. Infections due to contaminated water being used for religious practices 8, 12 have also been reported.

References

- Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. The immune response to Naegleria fowleri amebae and pathogenesis of infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51:243-59.

- Visvesvara GS. Free-living amebae as opportunistic agents of human disease. J Neuroparasitol. 2010;1.

- Yoder JS, Eddy BA, Visvesvara GS, Capewell L, Beach MJ. The epidemiology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the USA, 1962-2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(7):968-75.

- Kemble SK, Lynfield R, DeVries AS, Drehner DM, Pomputius WF 3rd, Beach MJ, Visvesvara GS, da Silva AJ, Hill VR, Yoder JS, Xiao L, Smith KE, Danila R. Fatal Naegleria fowleri infection acquired in Minnesota: possible expanded range of a deadly thermophilic organism. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:805-9.

- Marciano-Cabral F, MacLean R, Mensah A, LaPat-Polasko L. Identification of Naegleria fowleri in domestic water sources by nested PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(10):5864-9.

- Cope JR, Ratard RC, Hill VR, Sokol T, Causey JJ, Yoder JS, Mirani G, Mull B, Mukerjee KA, Narayanan J, Doucet M, Qvarstrom Y, Poole CN, Akingbola OA, Ritter JM, Xiong Z, da Silva A, Roellig D, Van Dyke R, Stern H, Xiao L, Beach MJ. The first association of a primary amebic meningoencephalitis death with culturable Naegleria fowleri in tap water from a U.S. treated public drinking water system. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;doi:10.1093/cid/civ017.

- Yoder JS, Straif-Bourgeois S, Roy SL, Moore TA, Visvesvara GS, Ratard RC, Hill V, Wilson JD, Linscott AJ, Crager R, Kozak NA, Sriram R, Narayanan J, Mull B, Kahler AM, Schneeberger C, da Silva AJ, Beach MJ. Deaths from Naegleria fowleri associated with sinus irrigation with tap water: a review of the changing epidemiology of primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;1-7.

- CDC. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis associated with ritual nasal rinsing — St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(45):903.

- Anderson K, Jamieson A. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis. Lancet. 1972;1:902–3.

- Dorsch MM, Cameron AS, Robinson BS. The epidemiology and control of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis with particular reference to South Australia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:372-7.

- Puzon GJ, Lancaster JA, Wylie JT, Plumb IJ. Rapid detection of Naegleria fowleri in water distribution pipeline biofilms and drinking water samples.Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(17):6691-6.

- Shakoor S, Beg MA, Mahmood SF, Bandea R, Sriram R, Noman F, Ali F, Visvesvara GS, Zafar A. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria fowleri, Karachi, Pakistan. [PDF – 4 pages] Emerg Infect Dis. 2011:17;258-61.

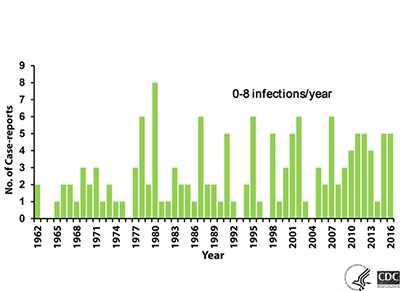

Number of PAM Infections

PAM is a rare* disease. From 1962-2016, 143 infections in the U.S. have been reported to CDC. Other infections have been diagnosed in stored autopsy samples dating back to 1937 1. The annual number of U.S. infections ranges from 0 to 8, with higher numbers appearing to occur in heat wave years when air and water temperatures are higher. It does not appear that the number of infections has increased since CDC established its Free-living Ameba (FLA) Laboratory and PAM registry in 1978.

References

- SN Gustavo. Fatal primary amebic meningoencephalitis. A retrospective study in Richmond, Virginia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970;54:737-42.

How PAM is Spread or Transmitted

You cannot get infected from drinking water contaminated with Naegleria. You can only be infected when contaminated water goes up into your nose.

Humans become infected when water containing Naegleria fowleri enters the nose, usually while swimming. People do not get infected by drinking contaminated water. The ameba migrates to the brain along the olfactory nerve, through a bony plate in the skull called the cribriform plate, where it reaches the brain and begins to destroy the brain tissue 1, 2. Naegleria fowleri has not been shown to spread via water vapor or aerosol droplets (such as shower mist or vapor generated from a humidifier). The ameba has never been shown to have spread from one person to another.

Transplantation of organs from donors infected by Naegleria fowleri has been recorded, although none of the organ recipients became infected 3-5. However, the occurrence of Naegleria fowleri outside the brain has been observed; Naegleria fowleri has been documented in tissue sections of lung, kidney, heart, spleen, and thyroid from two deceased PAM cases 6. As a result, although the risk of transmission of Naegleria fowleri by donor organs is still unknown, it is unlikely to be zero so the risks of transplantation with an organ possibly harboring Naegleria fowleri should be carefully weighed for each individual organ recipient against the potentially greater risk of delaying transplantation while waiting for another suitable organ. This warrants continued study of the benefits and risks of transplanting organs or tissues from people infected by Naegleria fowleri.

References

- Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. The immune response to Naegleria fowleri amebae and pathogenesis of infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51:243-59.

- Visvesvara GS. Free-living amebae as opportunistic agents of human disease. J Neuroparasitol. 2010;1.

- Kramer MH, Lerner CJ, Visvesvara GS. Kidney and liver transplants from a donor infected with Naegleria fowleri. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1032-3.

- Bennett WM, Nespral JF, Rosson MW, McEvoy KM. Use of organs for transplantation from a donor with primary meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1334-5.

- Tuppeny M. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis with subsequent organ procurement: a case study. J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;43(5):274-9.

- Roy SL, Metzger R, Chen JG, Laham FR, Martin M, Kipper SW, Smith LE, Lyon GM 3rd, Haffner J, Ross JE, Rye AK, Johnson W, Bodager D, Friedman M, Walsh DJ, Collins C, Inman B, Davis BJ, Robinson T, Paddock C, Zaki SR, Kuehnert M, DaSilva A, Qvarnstrom Y, Sriram R, Visvesvara GS. Risk for transmission of Naegleria fowleri from solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(1):163-71.

Who Gets Infected

PAM infections have been reported from around the world 1, 2. From 1962 through 2016, 143 infections have been documented in the U.S. Infections have occurred in all age groups, but 120 cases (84%) have occurred in children and adolescents (median age of 12 years; range 8 months to 66 years). Over three-quarters (>75%) of infections have been in males. Infected people were often reported to have participated in water-related activities such as swimming underwater, diving, and head dunking that could have caused water to go up the nose 3.

Naegleria fowleri has also been documented to infect animals such as cattle 4 and a South American tapir 5. Experimental infection can be induced in other species including mice, which are used as the model system for studying Naegleria fowleri infections resulting from swimming 6.

References

- Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. The immune response to Naegleria fowleri amebae and pathogenesis of infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51:243-59.

- Visvesvara GS. Free-living amebae as opportunistic agents of human disease. J Neuroparasitol. 2010;1.

- Yoder JS, Eddy BA, Visvesvara GS, Capewell L, Beach MJ. The epidemiology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the USA, 1962-2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(7):968-75.

- Visvesvara GS, De Jonckheere JF, Sriram R, Daft B. Isolation and molecular typing of Naegleria fowleri from the brain of a cow that died of primary amebic meningoencephalitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):4203-4.

- Lozano-Alarcón F, Bradley GA, Houser BS, Visvesvara GS. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri in a South American tapir. Vet Pathol. 1997;34:239-43.

- John DT, Nussbaum SL. Naegleria fowleri infection acquired by mice through swimming in amebae-contaminated water. J Parasitol. 1983;69:871-4.

When Infections Occur

Infections linked to freshwater swimming mostly occur during the heat of summer in July and August in the northern hemisphere when water temperatures peak and water levels are low 1. Infections can increase during heat wave years as water temperatures increase.

References

- Yoder JS, Eddy BA, Visvesvara GS, Capewell L, Beach MJ. The epidemiology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the USA, 1962-2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(7):968-75.

Risk of Infection

No data exist to accurately estimate the true risk of PAM. Hundreds of millions of visits to swimming venues occur each year in the U.S. 1 that result in 0-8 infections per year. The extremely low occurrence of PAM makes epidemiologic study difficult. It is unknown why certain persons become infected with the amebae while millions of others exposed to warm recreational fresh waters, including those who were swimming with people who became infected, do not. Attempts have been made to determine what concentration of Naegleria fowleri in the environment poses an unacceptable risk 2. However, no method currently exists that accurately and reproducibly measures the numbers of amebae in the water. This makes it unclear how a standard might be set to protect human health and how public health officials would measure and enforce such a standard.

References

- US Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012. Arts, Recreation, and Travel: Participation in Selected Sports Activities 2009. [XLS – 1 MB] 2012.

- Cabanes PA, Wallet F, Pringuez E, Pernin P. Assessing the risk of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis from swimming in the presence of environmental Naegleria fowleri. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(7):2927-31.

References

- Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. The immune response to Naegleria fowleri amebae and pathogenesis of infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol.2007;51:243-59.

- Visvesvara GS. Free-living amebae as opportunistic agents of human disease. J Neuroparasitol. 2010;1.

- Yoder JS, Eddy BA, Visvesvara GS, Capewell L, Beach MJ. The epidemiology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the USA, 1962-2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:968-75.

*Rare Disease

There is no universal definition of a “rare disease” but the U.S. Rare Disease Act of 2002 defined a rare disease as affecting less than 200,000 people in the U.S. and this definition has been adopted by the National Institutes of Health, Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Centers.

- Page last reviewed: February 28, 2017

- Page last updated: February 28, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir