Sources of Infection & Risk Factors

Balamuthia mandrillaris

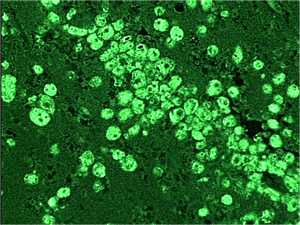

Balamuthia infection is a rare and often fatal disease 1. Since Balamuthia was first discovered in 1986, about 200 cases of infection have been reported worldwide 2,3,4. This number includes at least 70 confirmed cases in the United States. Because disease caused by Balamuthia is so uncommon, it is possible that there have been additional cases that were misdiagnosed 2,4.

Balamuthia amebas (single-celled living organisms) are thought to enter the body when soil containing Balamuthia comes in contact with skin wounds and cuts, or when dust containing Balamuthia is breathed in or gets in the mouth 1. Once inside the body, the amebas can then travel to the brain and cause Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis (GAE) 1. GAE is a severe disease of the brain that is fatal in over 89% of cases 2. It can take weeks to months to develop the first symptoms of Balamuthia GAE after initial exposure to the amebas 2,3.

Balamuthia amebas live freely in soil around the world 1-13. Gardening, playing with dirt, or breathing in soil carried by the wind might increase the risk for infection 1,2,5. Balamuthia might also be present in fresh water 1. There have been reports of Balamuthia GAE infection in dogs that swam in ponds. However, there have been no reported human cases where the only potential exposure was swimming.

An open wound, such as a cut or scrape, may be a potential entry point for Balamuthia.

The Balamuthia ameba is able to infect anyone, including healthy people 1-6. Those at increased risk for infection 1-4,6,10 include:

- People with HIV/AIDS, cancer, liver disease, or diabetes mellitus

- People taking immune system inhibiting drugs

- Alcoholics

- Young children or the elderly

- Pregnant women

In the United States, Balamuthia infection might be more common among Hispanic Americans 6,13. However, the cause of this trend is unknown and might be due to differences in exposure, biology, data collection, or other reasons 1,13-17. More research is needed to understand what factors might be associated with increased reporting among persons of Hispanic ethnicity.

There have been no reports of a Balamuthia infection spreading from one person to another except through organ donation/transplantation.

References

- Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp. , Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50(1):1-26.

- Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Balamuthia amoebic encephalitis: an emerging disease with fatal consequences. Microb Pathog. 2008;44(2):89-97.

- Perez MT, Bush LM. Balamuthia mandrillaris amebic encephalitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2007;9(4):323-8.

- Perez MT, Bush LM. Fatal amebic encephalitis caused by Balamuthia mandrillaris in an immunocompetent host: a clinicopathological review of pathogenic free-living amebae in human hosts. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11(6):440-7.

- Huang ZH, Ferrante A, Carter RF. Serum antibodies to Balamuthia mandrillaris, a free-living amoeba recently demonstrated to cause granulomatous amoebic encephalitis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(5):1305-8.

- Maciver SK. The threat from Balamuthia mandrillaris. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56(Pt 1):1-3.

- Balamuthia amebic encephalitis--California, 1999-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(28):768-71.

- Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS. Free-living amoebae as opportunistic and non-opportunistic pathogens of humans and animals. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34(9):1001-27.

- Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS. Opportunistic amoebae: challenges in prophylaxis and treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2004;7(1):41-51.

- Martinez AJ, Visvesvara GS. Free-living, amphizoic and opportunistic amebas. Brain Pathol. 1997;7(1):583-98.

- Bravo F, Sanchez MR. New and re-emerging cutaneous infectious diseases in Latin America and other geographic areas. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21(4):655-68, viii.

- Dunnebacke TH, Schuster FL, Yagi S, Booton GC. Isolation of Balamuthia amebas from the environment. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2003;50 Suppl:510-11.

- Schuster FL, Glaser C, Honarmand S, Maguire JH, Visvesvara GS. Balamuthia amebic encephalitis risk. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(8):1510-12.

- Schuster FL, Yagi S, Gavali S, Michelson D, Raghavan R, Blomquist I, Glastonbury C, Bollen AW, Scharnhorst D, Reed SL, Kuriyama S, Visvesvara V, Glaser CA. Under the Radar: Balamuthia Amebic Encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(7):879-87.

- Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS. Balamuthia mandrillaris. In: Khan N, ed. Emerging Protozoan Pathogens. London: Taylor & Francis; 2008.

- Schuster FL, Honarmand S, Visvesvara GS, Glaser CA. Detection of antibodies against free-living amoebae Balamuthia mandrillaris and Acanthamoeba species in a population of patients with encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(9):1260-1265.

- Schuster FL, Yagi S, Wilkins PP, Gavali S, Visvesvara GS, Glaser CA. Balamuthia mandrillaris, agent of amebic encephalitis: detection of serum antibodies and antigenic similarity of isolates by enzyme immunoassay. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2008;55(4):313-320.

- Page last reviewed: February 17, 2016

- Page last updated: February 17, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir