Diagnosis & Detection

Clinicians: For 24/7 diagnostic assistance, specimen collection guidance, shipping instructions, and treatment recommendations, please contact the CDC Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100.

Print-and-Go Fact Sheet

On This Page

Initial testing: CSF typically demonstrates a predominantly lymphocytic pleocytosis with typically fewer than 500 cells/mm3 1. CSF glucose concentration may be normal or low. There is usually a marked elevation of protein concentration (increasing from normal or mildly elevated early in the clinical course to >1000 mg/dL) 2,3. Balamuthia organisms are rarely seen in the CSF 3,4.

Balamuthia Case definition: In 2011, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) established a standard case definition for Balamuthia infections 5. Laboratory-confirmed Balamuthia infection is defined as the detection of Balamuthia as:

- Organisms in CSF, biopsy, or tissue specimens, or

- Nucleic acid in CSF, biopsy, or tissue specimens, or

- Antigen in CSF, biopsy, or tissue specimens.

Tests available: Diagnostic testing is not widely available for Balamuthia infection. Clinicians who suspect Balamuthia infection should contact their state health department and/or CDC (24/7 Emergency Operation Center—770-488-1700). CDC can assist with diagnosis and provide treatment recommendations. Telediagnosis can be arranged at CDC by emailing photos through DPDx, CDC’s telediagnosis tool. Instructions for submitting photos through DPDx are available at the DPDx Contact Us page.

Diagnostic Tests

Direct Visualization

CSF: Balamuthia trophozoites and/or cysts are rarely seen in the CSF. Every effort should be made to obtain brain tissue in order to make the diagnosis of Balamuthia GAE. If Balamuthia is identified in the CSF, the diagnosis of GAE should be subsequently confirmed with PCR or immunohistochemical tests of the CSF because host cells can be mistaken for Balamuthia. Note that a negative test on CSF does not rule out Balamuthia infection because the organism is not commonly present in the CSF.

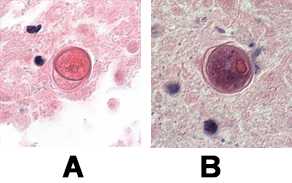

Tissue: The diagnosis of Balamuthia infection can be made by microscopic examination of tissue sections from biopsy specimens (skin lesions or brain tissue) stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)6 which might demonstrate trophozoites and/or cysts with morphology typical of Balamuthia (Figures A–D).

The cysts of Balamuthia mandrillaris are 6–30 µm in diameter (Figure A and B).Under a light microscope, the cysts appear to have two walls: a wrinkled fibrous outer wall (exocyst) and an inner wall (endocyst) that may be hexagonal, spherical, star-shaped or polygonal.Refractile granules might be observed below the inner wall. Pores are not evident in the wall complex. Cysts usually contain only one nucleus but occasionally have two nuclei.

A, B: Cysts of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with H&E. Images courtesy of the University of Kentucky Hospital, Lexington, Kentucky.

Trophozoites of Balamuthia mandrillaris are pleomorphic and measure approximately 12–60 µm (Figure C and D). They often produce long, slender pseudopodia. Trophozoites are usually uninucleate but binucleate forms are sometimes seen. The nucleus contains a large, centrally-located nucleolus but two or three nucleoli have been seen, especially in infected tissues; when present, multiple nucleoli distinguish B. mandrillaris from Acanthamoeba spp. There is no flagellated trophozoite stage as in Naegleria spp. 3,6,7.

C, D: Trophozoites of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with H&E.

Biopsies of skin lesions demonstrate granulomatous inflammation with infiltrating giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils; Balamuthia cysts or trophozoites can often be seen in tissue sections 8. Although most lesions are found in the skin or the brain, granulomas containing amebas have also been found in other organs including the lungs and kidneys 9.

E: Indirect Immunofluorescence (IIF) assay for Balamuthia mandrillaris.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Testing

An increasing number of PCR-based techniques (conventional and real-time PCR) have been described for detection and identification of free-living amebae in clinical samples, but are only available in selected reference laboratories. A real-time PCR was developed at CDC for simultaneous identification of Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Acanthamoeba species in clinical samples. This assay uses distinct primers and TaqMan probes for the simultaneous identification of these three amebae 10. Culture may be used to amplify the number of organisms for PCR testing, but is not used alone for diagnostic testing. Unlike Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia cannot be grown on agar plates coated with bacteria but requires mammalian cell cultures (such as monkey kidney [E6] or human lung fibroblasts) for laboratory cultivation 7.

Antigen Detection

Detecting Balamuthia mandrillaris antigen involves immunohistochemical staining techniques, such as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) staining and immune alkaline phosphatase staining (IHC), which use an antibody specific for Balamuthia mandrillaris followed by microscopic examination to identify Balamuthia mandrillaris in tissue, culture, or CSF.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) techniques employing rabbit anti-ameba sera 3, 11 with subsequent microscopic examination can identify Balamuthia in tissue, culture, or CSF. Three IHC methods are available: indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) staining (Figure E), immune peroxidase staining, or immune alkaline phosphatase staining.

Serology

Diagnostic Tests Offered by CDC

Below are instructions for submitting specimens to CDC for free-living ameba testing. Please see the CDC Infectious Diseases Laboratory Test Directory for additional information.

Specimens can be sent to CDC for diagnostic assistance. If possible, please send the following specimens:

-

Fresh, unfixed CSF or tissue

- If the specimen has been previously frozen or is preserved in formalin, CDC will still accept the specimen but the full range of testing methodologies might not be available.

-

Paraffin-embedded and formalin-fixed tissue

- Preferably a few H&E-stained slides and a few [about 6] unstained slides, or

- Paraffin-embedded tissue block

- Sera (two samples taken 2 weeks apart)

Fresh, unfixed specimens (i.e., CSF and tissue) should be sent at ambient temperature by overnight priority mail. Please ship these specimens separately from other chilled or frozen samples being shipped.

If the specimen (i.e., CSF or tissue) has been previously frozen or is preserved in formalin, CDC will still accept the specimen but the full range of testing methodologies might not be available. Please send these specimens by overnight priority mail on ice packs (if tissue is frozen) (do NOT ship on dry ice) and ambient temperature if the tissue is fixed in formalin.

Care should be taken to pack glass slides securely, as they can be damaged in shipment if not packed in a crush-proof container.

Serum specimens can be collected from the patient in a red-top tube (plain vacuum tube with no additive) or a serum-separator tube (tiger top) tube (red/gray speckled top with gel in the tube). Please centrifuge the specimen, and if possible, send serum only. If using a plain red-top tube, you must separate the serum before shipping and send the serum only. Serum samples should be shipped refrigerated or frozen and packed with cold packs.

Please use the CDC specimen submission form [PDF – 2 pages] and send to the address below. Be sure to add the pertinent travel history as well as relevant clinical history and any results from previous infectious disease testing. Please arrange Monday–Friday delivery only. Packages cannot be accepted on weekends or federal holidays.

CDC Shipping address:

CDC

SMB/STAT

Attn: Unit 53

1600 Clifton Road, NE

Atlanta, GA 30333

USA

See Specimen Submission Guidelines for Pathologic Evaluation of CNS Infections for more information.

Telediagnosis can be arranged at CDC by emailing photos through DPDx, CDC’s telediagnosis tool. Instructions for submitting photos through DPDx are available at the DPDx Contact Us page.

References

- Visvesvara GS, Roy SL, Maguire JH. Pathogenic and Opportunistic Free-Living Amebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia pedata. Tropical Infectious Diseases—Principles, Pathogens, & Practice, 3rd ed. Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF, editors. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone. 2001;707–13.

- Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS. Free-living amoebae as opportunistic and non-opportunistic pathogens of humans and animals. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34(9):1001-27.

- Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp. , Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50(1):1-26.

- Jayasekera S, Sissons J, Tucker J, Rogers C, Nolder D, Warhurst D, Alsam S, White JML, Higgins EM, Khan NA. Post-mortem culture of Balamuthia mandrillaris from the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of a case of granulomatous amoebic meningoencephalitis, using human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53(10):1007–12.

- Council for State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE). Case definitions for non-notifiable infections caused by free-living amebae (Naegleria fowleri, Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Acanthamoeba spp.). [PDF – 10 pages] Infectious Disease Committee. 2012.

- Martinez AJ, Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS. Balamuthia mandrillaris: its pathogenic potential. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2001;Suppl:6S-9S.

- Visvesvara GS, Schuster FL, Martinez AJ. Balamuthia mandrillaris, N. G., N. Sp, agent of amebic meningoencephalitis in humans and other animals. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:504–14.

- Bravo FG, Cabrera J, Gottuzo E, Visvesvara GS. Cutaneous manifestations of infection by free-living amebas. Tropical Dermatology. Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, editors. Philadelphia: Elsevier. 2006. pp. 49–55.

- Martinez AJ, Visvesvara GS. Free-living, amphizoic and opportunistic amebas. Brain Pathol. 1997;7:583–98.

- Qvarnstrom Y, Visvesvara GS, Sriram R, da Silva AJ. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Naegleria fowleri. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(10):3589-95.

- da Rocha-Azevedo B, Tanowitz HB, Marciano-Cabral F. Diagnosis of infections caused by pathogenic free-living amoebae. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;2009:251406.

- Jackson BR, Kucerova Z, Roy SL, Aguirre G, Weiss J, Sriram R, Yoder J, Foelber R, Baty S, Derado G, Stramer SL, Winkelman V, Visvesvara G. Serologic survey for exposure following fatal Balamuthia mandrillaris infection. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:1305–11.

- Page last reviewed: August 3, 2017

- Page last updated: August 3, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir