From U.S. Borders to Your Community - Saving Lives 24/7

A response always starts with a call, no matter what time of day or night.

Located at 20 U.S. airports, seaports, and land border crossings, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Quarantine Stations serve on CDC’s frontlines to protect the public’s health at U.S. ports of entry. These stations connect locally with state and local health departments and globally with the ministries of health in various countries.

Staff at the quarantine stations work with partners to protect the health of communities from contagious diseases that are just a flight, cruise, or border crossing away. Their many duties include responding to reports of ill passengers arriving from international travel, sending life-saving drugs to patients with certain conditions, and conducting investigations when an ill person onboard an airplane or ship may have infected others who need to be notified about their exposure.

It’s all part of our 24/7 work at CDC…

CDC Quarantine Station and State Troopers Team Up to Help Save Lives

A CDC public health officer enlists partners to get life-saving drugs to patients.

Looking forward to a relaxing weekend with her family, Lisa Poray took the train home on a cold January Friday night—an hour’s ride from her work as a quarantine public health officer at the Chicago O’Hare International Airport. The minute she walked in her door at 7 p.m. she got a call from CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC). That night, she was on call for the CDC Chicago Quarantine Station.

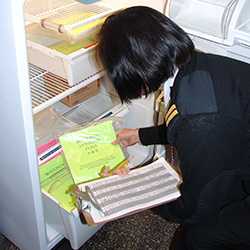

Than Lerner, Quarantine Public Health Officer, inspects drugs stored at CDC’s Seattle Quarantine Station. Photo Credit: CDC / Gaby Benenson

The urgent call on January 21, 2011, was a request to ship diphtheria antitoxin—an essential treatment for this rare but life-threatening infection—to Madison, Wisconsin.

When authorized, select CDC Quarantine Stations release emergency drugs, such as artesunate for malaria and antitoxins for botulism and diphtheria. Because the stations are located at airports, they are well situated to get the drugs out as soon as possible on the next available flight. In 2011, CDC Quarantine Stations released 153 drug shipments.

Making connections

Officer Poray turned on her computer to look for the earliest flight to Madison: no more flights that night. The earliest flight was at 7:15 a.m. the next morning. The shipment would have to be prepared and given to the airline 45 minutes before flight time at another terminal.

She talked to the doctor at the hospital handling the case and the hospital pharmacist who arranged for pick-up at the airport. Since these antitoxins are rarely used, the professional staff often have questions. Poray made sure the doctor and pharmacist knew how to reach the CDC specialists on call for diphtheria so they could discuss the case and the dosage, and how to prepare and administer the treatment.

Next, Poray had to schedule a babysitter for her two children, aged 8 and 11, since she would have to leave at 5:00 am. Her children knew the drill whenever their mom had to respond to emergencies.

She had just drifted off to sleep when she got another call at 10:10 p.m. A shipment of artesunate was needed for a patient with malaria in Merrillville, Indiana.

No flight available

The major airlines had no flights to Merrillville. She looked up the closest airport: Indianapolis. How to get the package to its final destination?

State police, she thought.

Poray got authorization from the station’s assistant officer in charge to request help from the state police. Illinois state police would coordinate with Indiana state police.

Unfortunately, the state police 24/7 emergency number shown on the Internet was unstaffed and responded with only a recording. She was not getting anywhere. Poray called CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC).

“Can you help me?” she asked the EOC duty officer.

“No problem. That’s what we do,” Lee Miller reassured her, and he found all the numbers needed.

Lisa Poray, Quarantine Public Health Officer in Chicago, wraps a shipment of life saving drugs. Photo Credit: CDC / Shannon Bachar

Four degrees of separation

From there, it was four degrees of separation to get a human chain to deliver the drugs to the patient’s hospital. The Illinois Emergency Management Agency Communications Center contacted the Illinois Department of Public Health duty officer, who got the Illinois State Police Emergency Operation Center liaison, who connected with the Indiana state troopers.

Miller arranged a conference call with everyone in the chain. They discussed how to relay the drugs securely. A packing slip would be designed so every party could sign it, hand it off to the next person, and fax it back to Poray, who would keep track of the relay. The conference call ended at midnight.

Poray left for the airport at 4 a.m., so she would have time to prepare the shipments for both Wisconsin and Indiana. At 6:00 a.m., the Illinois state trooper met her at the airport to pick up the artesunate. At 8:08 a.m., he transferred the package to the Indiana trooper. By 9:00 a.m., the package reached the hospital in Merrillville. Meanwhile at 6:30 a.m., Poray dropped off the diphtheria antitoxin at United Airlines for the 7:13 a.m. flight to Madison, Wisconsin.

Poray got home in time to take her kids to their Saturday morning ice-skating lessons.

“These calls seem to come at the worst possible time, but it gives me a good feeling that I’m helping someone. My kids are proud of me for my work, and they know when that call comes in, it’s important.”

Related Links

- Page last reviewed: December 23, 2016

- Page last updated: December 23, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir