Facts about Coarctation of the Aorta

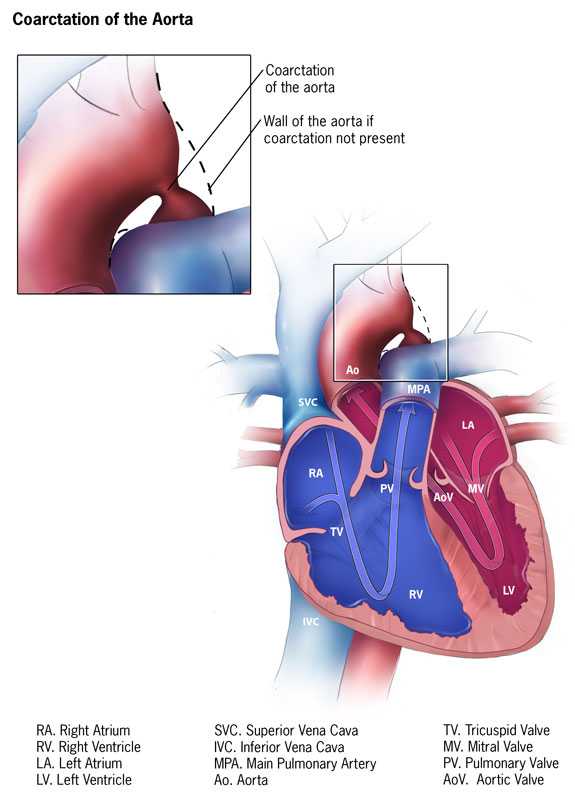

Coarctation (pronounced koh-ark-TEY-shun) of the aorta is a birth defect in which a part of the aorta, the tube that carries oxygen-rich blood to the body, is narrower than usual.

What is Coarctation of the Aorta?

Coarctation of the aorta is a birth defect in which a part of the aorta is narrower than usual.If the narrowing is severe enough and if it is not diagnosed, the baby may have serious problems and may need surgery or other procedures soon after birth. For this reason, coarctation of the aorta is often considered a critical congenital heart defect. The defect occurs when a baby’s aorta does not form correctly as the baby grows and develops during pregnancy. The narrowing of the aorta usually happens in the part of the blood vessel just after the arteries branch off to take blood to the head and arms, near the patent ductus arteriosus, although sometimes the narrowing occurs before or after the ductus arteriosus. In some babies with coarctation, it is thought that some tissue from the wall of ductus arteriosus blends into the tissue of the aorta. When the tissue tightens and allows the ductus arteriosus to close normally after birth, this extra tissue may also tighten and narrow the aorta.

The narrowing, or coarctation, blocks normal blood flow to the body. This can back up flow into the left ventricle of the heart, making the muscles in this ventricle work harder to get blood out of the heart. Since the narrowing of the aorta is usually located after arteries branch to the upper body, coarctation in this region can lead to normal or high blood pressure and pulsing of blood in the head and arms and low blood pressure and weak pulses in the legs and lower body.

If the condition is very severe, enough blood may not be able to get through to the lower body. The extra work on the heart can cause the walls of the heart to become thicker in order to pump harder. This eventually weakens the heart muscle. If the aorta is not widened, the heart may weaken enough that it leads to heart failure. Coarctation of the aorta often occurs with other congenital heart defects.

Learn more about how the heart works »

Occurrence

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 4 out of every 10,000 babies are born each year in the United States with coarctation of the aorta 1.

Nicholas’s Story

Nicholas was born with coarctation of the aorta. Read his story as well as other stories from families affected by coarctation of the aorta »

Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of heart defects, including coarctation of the aorta, among most babies are unknown. Some babies have heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. Heart defects, like coarctation of the aorta, are also thought to be caused by a combination of genes and other risk factors, such as things the mother comes in contact with in the environment, what the mother eats or drinks, or medicines the mother uses.

Read more about CDC’s work on causes and risk factors for birth defects »

Diagnosis

Coarctation of the aorta is usually diagnosed after the baby is born. How early in life the defect is diagnosed usually depends on how mild or severe the symptoms are. Those with severe narrowing will have symptoms early in life, while babies with mild narrowing may never have problems, or signs may not be detected until later in life.

In babies with a more serious condition, early signs usually include:

- pale skin

- irritability

- heavy sweating

- difficulty breathing

Detection of the defect is often made during a physical exam. In infants and older individuals, the pulse will be noticeably weaker in the legs or groin than it is in the arms or neck, and a heart murmur—an abnormal whooshing sound caused by disrupted blood flow—may be heard through a doctor’s stethoscope. Older children and adults with coarctation of the aorta often have high blood pressure in the arms.

Once suspected, an echocardiogram is the most commonly used test to confirm the diagnosis. An echocardiogram is an ultrasound of the heart that can show problems with the structure of the heart and the blood flow through it, and how well the heart is working. It will show the location and severity of the coarctation and whether any other heart defects are present. Other tests to measure the function of the heart may be used including chest x-ray, electrocardiogram (EKG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cardiac catheterization.

Coarctation of the aorta is often considered a critical congenital heart defect (critical CHD) because if the narrowing is severe enough and it is not diagnosed, the baby may have serious problems soon after birth. CCHDs also can be detected with newborn pulse oximetry screening. Pulse oximetry is a simple bedside test to determine the amount of oxygen in a baby’s blood. Low levels of oxygen in the blood can be a sign of a CCHD. Newborn screening using pulse oximetry can identify some infants with a CCHD, like coarctation of the aorta, before they show any symptoms.

Treatments

No matter what age the defect is diagnosed, the narrow aorta will need to be widened once symptoms are present. This can be done with surgery or a procedure called balloon angioplasty. A balloon angioplasty is a procedure that uses a thin, flexible tube, called a catheter, which is inserted into a blood vessel and directed to the aorta. When the catheter reaches the narrow area of the aorta, a balloon at the tip is inflated to expand the blood vessel. Sometimes a mesh-covered tube (stent) is inserted to keep the vessel open. The stent is used more often to initially widen the aorta or re-widen it if the aorta narrows again after surgery has been performed. During surgery to correct a coarctation, the narrow portion is removed and the aorta is reconstructed or patched to allow blood to flow normally through the aorta.

Even after surgery, children with a coarctation of the aorta often have high blood pressure that is treated with medicine. It is important for children and adults with coarctation of the aorta to follow up regularly with a cardiologist (a heart doctor) to monitor their progress and check for other health conditions that might develop as they get older.

Reference

- Bjornard, K., Riehle-Colarusso, T., Gilboa, S. M. and Correa, A. Patterns in the prevalence of congenital heart defects, metropolitan Atlanta, 1978 to 2005. Birth Defects Res Part A: Clin Mol Teratol. 2013;97:87–94.

- Page last reviewed: February 11, 2016

- Page last updated: September 26, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir