Hepatitis A Questions and Answers for Health Professionals

Index of Questions

- What is the case definition for acute hepatitis A?

- How common is hepatitis A virus infection in the United States?

- How is the hepatitis A virus (HAV) transmitted?

- Who is at increased risk for acquiring hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection?

- What are the signs and symptoms of hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection?

- When symptoms occur, how long do they last?

- What is the incubation period for hepatitis A virus (HAV)?

- How long does hepatitis A virus (HAV) survive outside the body?

- How is the hepatitis A virus (HAV) killed?

- Can hepatitis A become chronic?

- Can persons become re-infected with hepatitis A?

- How is HAV infection prevented?

- Who should be vaccinated against hepatitis A?

- Which hepatitis A vaccines are licensed for use in the United States?

- What are the dosages and schedules for hepatitis A vaccines?

- How long does protection from hepatitis A vaccine last?

- Can hepatitis A vaccine be administered concurrently with other vaccines?

- Can a patient receive the first dose of hepatitis A vaccine from one manufacturer and the second (last) dose from another manufacturer?

- What should be done if an infant receives the first dose of hepatitis A vaccine at an age younger than 12 months?

- What should be done if the second (last) dose of hepatitis A vaccine is delayed?

- Can hepatitis A vaccine be given during pregnancy?

- Can hepatitis A vaccine be given to immunocompromised persons (e.g., persons on hemodialysis or persons with AIDS)?

- Is it harmful to administer an extra dose(s) of hepatitis A vaccine or to repeat the entire vaccine series if documentation of vaccination history is unavailable?

- Is it worthwhile to administer the first dose of hepatitis A vaccine if the timing of the second dose cannot be assured?

- Should prevaccination testing be performed before administering hepatitis A vaccine?

- Should postvaccination testing be performed?

- Which groups do NOT need routine vaccination against hepatitis A?

± Hepatitis A and International Travel

± Postexposure Prophylaxis for Hepatitis A

- What are the current CDC guidelines for postexposure protection against hepatitis A?

- Who requires protection (i.e., immune globulin [IG] or hepatitis A vaccine) after exposure to HAV?

- If a case of hepatitis A is found in a setting providing services to children or adults, such as a school, hospital, office setting, corrections facility or homeless shelter, what should be done?

- Should hepatitis A vaccine be recommended for individuals displaced by a disaster?

Overview and Statistics

What is the case definition for acute hepatitis A?

The clinical case definition for acute viral hepatitis is discrete onset of symptoms consistent with hepatitis (e.g., nausea, anorexia, fever, malaise, or abdominal pain) AND either jaundice or elevated serum aminotransferase levels. Because the clinical characteristics are the same for all types of acute viral hepatitis, hepatitis A diagnosis must be confirmed by a positive serologic test for immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody to hepatitis A virus, or the case must meet the clinical case definition and occur in a person who has an epidemiologic link with a person who has laboratory-confirmed hepatitis A (i.e., household or sexual contact with an infected person during the 15–50 days before the onset of symptoms).

The case definition for acute hepatitis A is available at the following link: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/hepatitis-a-acute/case-definition/2012/

Additional guidance on viral hepatitis surveillance and case management is available here: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/surveillanceguidelines.htm.

Additional information on hepatitis A serology is available here:

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/resources/professionals/training/serology/training.htm

How common is hepatitis A virus infection in the United States?

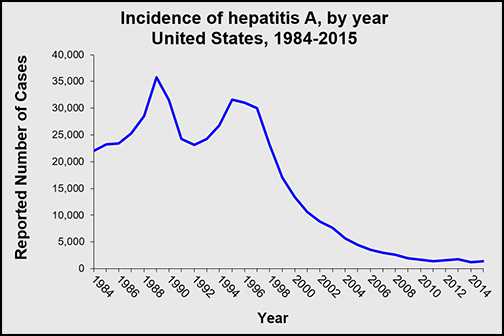

Hepatitis A rates in the United States have declined by more than 95% since hepatitis A vaccine first became available in 1995. (National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/mmwr_nd/index.html)

In 2015, a total of 1,390 cases of hepatitis A were reported to CDC from 50 states, a 12.2% increase from the number of reported cases in 2014. However, the overall incidence rate in 2015 was 0.4 cases per 100,000 population, the same as 2014. After adjusting for under-ascertainment and under-reporting, an estimated 2,800 hepatitis A cases occurred in 2015. More information on hepatitis A surveillance is available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2015surveillance/index.htm.

How is the hepatitis A virus (HAV) transmitted?

- Person-to-person transmission through the fecal-oral route (i.e., ingestion of something that has been contaminated with the feces of an infected person) is the primary means of HAV transmission in the United States. Infections in the United States result primarily from travel to another country where hepatitis A virus transmission is common, close personal contact with infected persons, sex among men who have sex with men, and behaviors associated with injection drug use (1,2) (see https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2015surveillance/index.htm).

- Exposure to contaminated food or water can cause common-source outbreaks and sporadic cases of HAV infection. Uncooked foods contaminated with HAV can be a source of outbreaks, as well as cooked foods that are not heated to temperatures capable of killing the virus during preparation (i.e., 185 degrees F [>85 degrees C] for one minute) and foods that are contaminated after cooking, as occurs in outbreaks associated with infected food handlers (3–5). Waterborne outbreaks are infrequent in developed countries with properly maintained sanitation and water supplies (6). In the United States, floods are unlikely to cause outbreaks of communicable diseases, and outbreaks of HAV caused by flooding have not been documented (see https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/floods/after.html).

Who is at increased risk for acquiring hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection?

- Persons with direct contact with persons who have hepatitis A

- Travelers to countries with high or intermediate endemicity of HAV infection

- Men who have sex with men

- Users of injection and non-injection drugs

- Persons with clotting factor disorders

- Persons working with nonhuman primates

- Household members and other close personal contacts of adopted children newly arriving from countries with high or intermediate hepatitis A endemicity

(Prevention of Hepatitis A Through Active or Passive Immunization Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [ACIP] https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5507a1.htm; Prevention of Hepatitis A Through Active or Passive Immunization: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00048084.htm)

What are the signs and symptoms of hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection?

Among older children and adults, infection is typically symptomatic. Symptoms usually occur abruptly and can include the following:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Dark urine

- Clay-colored bowel movements

- Joint pain

- Jaundice

Most (70%) of infections in children younger than age 6 are not accompanied by symptoms. When symptoms are present, young children typically do not have jaundice; most (>70%) older children and adults with HAV infection have this symptom (7,8).

When symptoms occur, how long do they last?

Symptoms of hepatitis A usually last less than 2 months, although 10%–15% of symptomatic persons have prolonged or relapsing disease for up to 6 months (9–13).

What is the incubation period for hepatitis A virus (HAV)?

The average incubation period for HAV is 28 days (range: 15–50 days) (6,14–15).

How long does hepatitis A virus (HAV) survive outside the body?

HAV can live outside the body for months, depending on the environmental conditions.

How is the hepatitis A virus (HAV) killed?

In contaminated food, HAV is killed when exposed to temperatures of >185 degrees F (>85 degrees C) for 1 minute. However, the virus can still be spread from cooked food that is contaminated after cooking. Freezing does not inactivate HAV.

Adequate chlorination of water, as recommended in the United States, kills HAV that enters the municipal water supply (5,16–17). Transmission of HAV from exposure to contaminated water is considered rare given that no substantial or consistent increase in prevalence of anti-HAV has been documented among sewage workers.

In the environment, HAV can be killed by cleaning household or other facility surfaces with a freshly prepared solution of 1:100 dilution of household bleach to water (18).

Can hepatitis A become chronic?

No. Hepatitis A does not become chronic.

Can persons become re-infected with hepatitis A?

No. IgG antibodies to HAV, which appear early in the course of infection, provide lifelong protection against the disease (10).

How is HAV infection prevented?

Vaccination with the full, two-dose series of hepatitis A vaccine is the best way to prevent HAV infection. Hepatitis A vaccine has been licensed in the United States for use in persons 1 year of age and older. Additional Guidance is available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5507a1.htm.

Immune globulin can provide short-term protection against hepatitis A, both pre- and post-exposure. Immune globulin must be administered within 2 weeks after exposure for maximum protection. Additional Guidance is available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6636a5.htm?s_cid=mm6636a5_e.

Given that the virus is transmitted through the fecal-oral route, good hand hygiene—including handwashing after using the bathroom, changing diapers, and before preparing or eating food—is integral to hepatitis A prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/show-me-the-science.html).

Hepatitis A Vaccination

Who should be vaccinated against hepatitis A?

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that the following persons be vaccinated against hepatitis A:

- All children at age 1 year,

- Persons who are at increased risk for infection,

- Persons who are at increased risk for complications from hepatitis A, and

- Any person wishing to obtain immunity (protection).

Children

Persons at Increased Risk for Hepatitis A Infection

Persons traveling to or working in countries that have high or intermediate endemicity of hepatitis A. Persons who travel to developing countries are at high risk for hepatitis A, even those traveling to urban areas, staying in luxury hotels, and those who report maintaining good hand hygiene and being careful about what they drink and eat (see https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/hepatitis-a for more information).

Men who have sex with men. Men who have sex with men should be vaccinated.

Users of injection and non-injection drugs. Persons who use injection and non-injection drugs should be vaccinated.

Persons who have occupational risk for infection. Persons who work with HAV-infected primates or with HAV in a research laboratory setting should be vaccinated. No other groups have been shown to be at increased risk for HAV infection because of occupational exposure.

Persons who have chronic liver disease. Persons with chronic liver disease who have never had hepatitis A should be vaccinated, as they have a higher likelihood of having fulminant hepatitis A (i.e., rapid onset of liver failure, often leading to death). Persons who are either awaiting or have received liver transplants also should be vaccinated.

Persons who have clotting-factor disorders. Persons who have never had hepatitis A and who are administered clotting-factor concentrates, especially solvent detergent-treated preparations, should be vaccinated.

Household members and other close personal contacts of adopted children newly arriving from countries with high or intermediate hepatitis A endemicity. Previously unvaccinated persons who anticipate close personal contact (e.g., household contact or regular babysitting) with an international adoptee from a country of high or intermediate endemicity during the first 60 days following arrival of the adoptee in the United States should be vaccinated. The first dose of the 2-dose hepatitis A vaccine series should be administered as soon as adoption is planned, ideally 2 or more weeks before the arrival of the adoptee. More information is available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5836a4.htm.

Persons with direct contact with persons who have hepatitis A. Persons who have been recently exposed to HAV and who have not previously received hepatitis A vaccine should be vaccinated.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm

Which hepatitis A vaccines are licensed for use in the United States?

Two single-antigen hepatitis A vaccines and one combination vaccine are currently licensed in the United States. All are inactivated vaccines.

Single-antigen hepatitis A vaccines

- HAVRIX® (manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline) [PDF – 16 pages]

- VAQTA® (manufactured by Merck & Co., Inc) [PDF – 18 pages]

Combination vaccine

What are the dosages and schedules for hepatitis A vaccines?

HAVRIX ® 1

|

Licensed dosages and schedules for HAVRIX ® 1

|

||||

| Age | Dose (ELISA units)2 | Volume (mL) | No. of doses | Schedule (mos)3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 mos–18 yrs | 720 | 0.5 | 2 | 0,6-12 |

| ≥19 years | 1,440 | 1.0 | 2 | 0,6-12 |

1Hepatitis A vaccine, inactivated, GlaxoSmithKline.

2Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units.

30 months represents timing of the initial dose; subsequent numbers represent months after the initial dose.

VAQTA ® 1

|

Licensed dosages and schedules for VAQTA ® 1

|

||||

| Age | Dose (U.)2 | Volume (mL) | No. of doses | Schedule (mos)3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 mos–18 yrs | 25 | 0.5 | 2 | 0,6-18 |

| ≥19 years | 50 | 1.0 | 2 | 0,6-18 |

1Hepatitis A vaccine, inactivated, Merck & Co., Inc.

2Units.

30 months represents timing of the initial dose; subsequent numbers represent months after the initial dose.

TWINRIX ® 1 (HepAHepB) Vaccine Schedule (Not recommended for post exposure prophylaxis)

|

Licensed dosages and schedules for TWINRIX ® 1

|

||||

| Age | Dose (ELISA units)2 | Volume (mL) | No. of doses | Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 18 yrs | 720 | 1.0 | 3 | 0, 1, 6 mos |

| ≥ 18 yrs | 720 | 1.0 | 4 | 0, 7, 21–30 days + 12 mos3 |

1Combined hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine, inactivated, GlaxoSmithKline.

2Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units.

3This 4-dose schedule enables patients to receive 3 doses in 21 days; this schedule is used prior to planned exposure with short notice and requires a fourth dose at 12 months.

How long does protection from hepatitis A vaccine last?

The exact duration of protection after vaccination is unknown. Anti-HAV has been shown to persist for at least 20 years in adults administered inactivated vaccine as children with the three-dose schedule (19), and anti-HAV persistence of at least 20 years also was demonstrated among persons vaccinated with a two-dose schedule as adults (20). Detectable antibodies are estimated to persist for 40 years or longer based on mathematical modeling and anti-HAV kinetic studies (20, 21).

Can hepatitis A vaccine be administered concurrently with other vaccines?

Yes. Hepatitis B, diphtheria, poliovirus (oral and inactivated), tetanus, typhoid (oral and intramuscular), cholera, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, and yellow fever vaccines can be given at the same time that hepatitis A vaccine is given, but at a different injection site (22, 23–25). In studies among young children, simultaneous administration of hepatitis A vaccine did not affect the immunogenicity or reactogenicity of diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis; inactivated polio; measles, mumps, rubella (MMR); hepatitis B; and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines. (22, 26–27)

Can a patient receive the first dose of hepatitis A vaccine from one manufacturer and the second (last) dose from another manufacturer?

Yes. Results of several studies indicate that the response of adults administered hepatitis A vaccine according to a schedule that mixed the two single-antigen vaccines currently licensed in the United States was equivalent to that of adults vaccinated according to the licensed schedules with the single vaccine (28–29).

What should be done if an infant receives the first dose of hepatitis A vaccine at an age younger than 12 months?

Although no known harm is associated with giving hepatitis A vaccine to infants, the hepatitis A vaccine dose(s) administered prior to 12 months of age might result in a suboptimal immune response, particularly in infants with passively acquired maternal antibody (30–31). Therefore, hepatitis A vaccine dose(s) administered at <12 months of age are not considered valid doses.

The hepatitis A vaccine two-dose series should be initiated starting at least 6 months after the last invalid dose and when the child is at least 1 year of age.

What should be done if the second (last) dose of hepatitis A vaccine is delayed?

The second dose should be given as soon as possible. Even if the second does is delayed, the first dose does not need to be repeated.

Can hepatitis A vaccine be given during pregnancy?

Yes. Hepatitis A vaccine is recommended for pregnant women with additional medical conditions or other indications for hepatitis A vaccine. The Adult Immunization Schedule by Medical and Other Indications is available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/adult-conditions.html

A recent review of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) did not identify any concerning patterns of adverse events in pregnant women or their infants after hepatitis A vaccination (HAVRIX, VAQTA) or hepatitis A and B combined vaccination (TWINRIX) during pregnancy. (32) Pregnant women at risk for HAV infection during pregnancy should also be counseled concerning all options to prevent HAV infection.

Can Hepatitis A vaccine be given to immunocompromised persons (e.g., persons on hemodialysis or persons with AIDS)?

Yes. Because hepatitis A vaccine is inactivated, no special precautions need to be taken when vaccinating immunocompromised persons.

Is it harmful to administer an extra dose(s) of hepatitis A vaccine or to repeat the entire vaccine series if documentation of vaccination history is unavailable?

No. If necessary, administering extra doses of hepatitis A vaccine is not harmful.

Is it worthwhile to administer the first dose of hepatitis A vaccine if the timing of the second dose cannot be assured?

Yes, It is not known for how long protection from one hepatitis A vaccine dose lasts, but it has been shown to last for at least 10 years (33). One dose of single-antigen hepatitis A vaccine administered at any time before International travel can provide adequate protection for most healthy persons.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm

Should prevaccination testing be performed before administering hepatitis A vaccine?

To reduce the costs of vaccinating people who are already immune to hepatitis A, prevaccination testing is recommended only in certain persons, specific circumstances to reduce the costs of vaccinating people who are already immune to hepatitis A, including:

- Persons who were born in geographic areas with high or intermediate prevalence of HAV infection;

- Older adolescents and adults in certain population groups (i.e., American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Hispanics); and

- Adults in groups that have a high prevalence of infection (e.g., injection-drug users).

Prevaccination testing might also be warranted for older adults. The decision to test should be based on 1) the expected prevalence of immunity, 2) the cost of vaccination compared with the cost of serologic testing, and 3) the likelihood that testing will not interfere with initiation of vaccination (33). Additional information is available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5507a1.htm

Should postvaccination testing be performed?

No. Postvaccination testing is not indicated because of the high rate of vaccine response among adults and children. In addition, not all testing methods approved for routine diagnostic use in the United States have the sensitivity to detect low, but protective, anti-HAV concentrations after vaccination. Additional information is available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5507a1.htm

Which groups do NOT need routine vaccination against hepatitis A?

Food service workers. Foodborne hepatitis A outbreaks are relatively uncommon in the United States; however, when they occur, intensive public health efforts are required for their control.

Although persons who work as food handlers have a critical role in common-source foodborne outbreaks, they are not at increased risk for hepatitis A because of their occupation. Consideration may be given to vaccination of employees who work in areas where community-wide outbreaks are occurring and where state and local health authorities or private employers determine that such vaccination is cost-effective.

Sewage workers. In the United States, no work-related outbreaks of hepatitis A have been reported among workers exposed to sewage.

Health-care workers. Health-care workers are not at increased risk for hepatitis A. If a patient with hepatitis A is admitted to the hospital, routine infection-control precautions will prevent transmission to hospital staff.

Children under 12 months of age. Because of the limited experience with hepatitis A vaccination among children in this age group, the vaccine is not currently licensed for children age <12 months.

Child care center staff. The frequency of outbreaks of hepatitis A is not high enough in this setting to warrant routine hepatitis A vaccination of staff. Hepatitis A vaccination is recommended for all children at 1 year of age, including children attending child day care centers.

Immune Globulin

What Immune Globulin product is licensed in the United States?

GamaSTAN™ S/D is the only immune globulin (IG) product approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for hepatitis A virus prophylaxis. GamaSTAN™ S/D (Grifols Therapeutics, Inc., Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) is a sterile, preservative-free solution of IG for intramuscular administration and is used for prophylaxis against disease caused by infection with hepatitis A, measles, varicella, and rubella viruses. More information on GamaSTAN™ S/D is available at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/BloodBloodProducts/ApprovedProducts/LicensedProductsBLAs/FractionatedPlasmaProducts/UCM371376.pdf [PDF – 8 pages]

What dose of immune globulin should be used for pre- and post-exposure hepatitis A prophylaxis?

In July 2017, the prescribing information for GamaSTAN™ S/D was updated. Changes were made to the dosing instructions for hepatitis A pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis indications. These changes were made because of concerns about decreased HAV immunoglobulin G antibody (anti-HAV IgG) potency, likely resulting from decreasing prevalence of previous HAV infection among plasma donors, leading to declining anti-HAV antibody levels in donor plasma (35). More dosing information is available in the table below and at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6636a5.htm?s_cid=mm6636a5

Indications and dosage recommendations for GamaSTAN S/D human immune globulin for preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis against hepatitis A infection

| Indication | Dose |

| Preexposure prophylaxis | |

| Up to 1 month of travel | 0.1 mL/kg |

| Up to 2 months of travel | 0.2 mL/kg |

| 2 months of travel or longer | 0.2 mL/kg (repeat every 2 months) |

Hepatitis A and International Travel

Who should receive protection against hepatitis A before travel?

All susceptible persons traveling to or working in countries that have high or intermediate rates of hepatitis A should be vaccinated or receive immune globulin (IG) before traveling. Persons who travel to developing countries are at high risk for hepatitis A. Even those traveling to urban areas, staying in luxury hotels, and those reporting that they maintain good hand hygiene and are careful about what they drink and eat are at high risk. For more information on international travel and HAV, see CDC’s travel page at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/hepatitis-a, or ACIP updated recommendations on Prevention of Hepatitis A after Exposure to Hepatitis A Virus and in International Travelers at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm

How soon before international travel should the first dose of hepatitis A vaccine be given?

The first dose of hepatitis A vaccine should be administered as soon as travel is considered.

For optimal protection, older adults, immunocompromised persons, and persons with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions who are planning to depart in ≤2 weeks should receive the initial dose of vaccine and also can simultaneously be administered immune globulin at a separate anatomic injection site. Information on immune globulin dosing is available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6636a5.htm?s_cid=mm6636a5

Additional information on hepatitis A vaccine and travel is available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm

What should be done if a traveler cannot receive hepatitis A vaccine?

Travelers who are allergic to a vaccine component, who elect not to receive vaccine, or who are aged <12 months should receive a single dose of immune globulin, which provides effective protection against Hepatitis A virus infection for up to 2 months depending on the dosage given.

Information on immune globulin dosing is available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6636a5.htm?s_cid=mm6636a5_e

Indications and dosage recommendations for GamaSTAN S/D human immune globulin for preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis against hepatitis A infection

| Indication | Dose |

| Preexposure prophylaxis | |

| Up to 1 month of travel | 0.1 mL/kg |

| Up to 2 months of travel | 0.2 mL/kg |

| 2 months of travel or longer | 0.2 mL/kg (repeat every 2 months) |

What should be done for international travelers <12 months of age?

Because hepatitis A vaccine is currently not approved for use in this age group, immune globulin is recommended. Information on immune globulin dosing is available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6636a5.htm?s_cid=mm6636a5_e

The two-dose hepatitis A vaccine series should be initiated when the child is at least 1 year of age.

Postexposure Prophylaxis for Hepatitis A

What are the current CDC guidelines for postexposure protection against hepatitis A?

Persons who have been exposed recently to hepatitis A virus (HAV) and who have not been vaccinated should be administered one dose of single-antigen hepatitis A vaccine or immune globulin (IG) as soon as possible, within 2 weeks after exposure. The guidelines vary by age and health status:

- For healthy persons aged 12 months–40 years, single-antigen hepatitis A vaccine at the age-appropriate dose is preferred to IG because of the vaccine’s advantages, including long-term protection and ease of administration, as well as the equivalent efficacy of vaccine to IG.

- For persons aged >40 years, IG is preferred because of the absence of information regarding vaccine performance in this age group and because of the more severe manifestations of hepatitis A in older adults. The magnitude of the risk of HAV transmission from the exposure should be considered in decisions to use vaccine or IG in this age group.

- Vaccine can be used if IG cannot be obtained.

- IG should be used for children aged <12 months, immunocompromised persons, persons with chronic liver disease, and persons who are allergic to the vaccine or a vaccine component (see Footnote).

Information on immune globulin dosing is available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6636a5.htm?s_cid=mm6636a5_e

Footnote:

IG is indicated for persons at increased risk of severe or fatal hepatitis A infection. These persons include adults >40 years of age (particularly adults 75 years and older), persons with chronic liver disease (e.g., cirrhosis), and those who are immunocompromised.

- IG is indicated for persons with decreased response to hepatitis A vaccine, such as immunocompromised persons. Immunocompromised persons include, but are not limited to persons:

- with congenital or acquired immunodeficiency;

- with HIV/AIDS;

- with chronic renal failure/undergoing hemodialysis;

- who have received solid organ, bone marrow, or stem cell transplants;

- who have iatrogenic immunosuppression (diseases requiring treatment with immunosuppressive drugs [e.g., TNF-alpha inhibitors], including long-term systemic corticosteroids and radiation therapy. Immune status relative to the dose of immunosuppressive drugs should be assessed by the provider); and

- who are otherwise less capable of developing a normal response to immunization.

CDC does not have official guidance to define all subgroups of persons recommended to receive IG. Further clinical guidance should be obtained for patients whose immune status is unclear.

Who requires protection (i.e., immune globulin (IG) or hepatitis A vaccine) after exposure to HAV?

Close personal contacts. Close personal contacts of persons with serologically confirmed hepatitis A (i.e., through a blood test), including:

- household and sex contacts and

- persons who have shared injection drugs with someone with hepatitis A.

Consideration should also be given to providing IG or hepatitis A vaccine to persons with other types of ongoing, close personal contact with a person with hepatitis A (e.g., a regular babysitter or caretaker).

Child-care center staff, attendees, and attendees’ household members.

- Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) should be administered to all previously unvaccinated staff and attendees of child-care centers or homes if 1) one or more cases of hepatitis A is recognized in children or employees or 2) cases are recognized in two or more households of center attendees.

- In centers that provide care only to older children who no longer wear diapers, PEP should be administered only to classroom contacts of the index patient (not to children or staff in other classrooms).

- When an outbreak occurs (i.e., hepatitis A cases in three or more families), PEP should also be considered for members of households that have diaper-wearing children attending the center.

Persons exposed to a common source, such as an infected food handler. If a food handler receives a diagnosis of hepatitis A, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) should be administered to other food handlers at the same establishment. Because transmission to patrons is unlikely, PEP administration to patrons typically is not indicated but may be considered if 1) during the time when the food handler was likely to be infectious, the food handler both directly handled uncooked foods or foods after cooking and had diarrhea or poor hygienic practices, and 2) patrons can be identified and treated within 2 weeks of exposure.

In settings in which repeated exposures to HAV might have occurred (e.g., institutional cafeterias), stronger consideration of PEP use might be warranted.

If a case of hepatitis A is found in a setting providing services to children or adults, such as a school, hospital, office setting, corrections facility or homeless shelter, what should be done?

PEP is not routinely recommended when a single case of hepatitis A is identified in a school (other than a child care setting in which children wear diapers), in an office or other work setting, a corrections facility, or homeless shelter, and if the source of infection is outside of the setting. Similarly, hospital-based health-care workers are not recommended to receive PEP when a person who has hepatitis A is admitted to the facility; instead, careful hygienic practices should be emphasized.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5507a1.htm

If it is determined that hepatitis A has been spread among students in a school or among patients and staff in a hospital, PEP should be administered to unvaccinated persons who have had close contact with an infected person. Similarly, if hepatitis A has spread among occupants or staff in a homeless shelter or corrections facility, PEP should be administered to unvaccinated persons who have had close contact with an infected person.

Should hepatitis A vaccine be recommended for individuals displaced by a disaster?

Although hepatitis A vaccine is recommended for all children in the United States at age 1 year (i.e., 12-23 months) and high-risk adults, evacuation itself is not a specific indication for hepatitis A vaccination of previously unvaccinated children or adults unless exposure to hepatitis A virus is suspected. Persons who evacuate their homes under orderly conditions to a congregate setting where sanitary conditions prevail should not require hepatitis A vaccine as a result of their evacuation status, unless they have been evacuated from an area where exposure to hepatitis A virus is likely or have been exposed to persons with suspected or proven hepatitis A infection. Additional information is available at https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/disease/vaccrecdisplaced.html

References:

1. Purcell RH. Relative infectivity of hepatitis A virus by the oral and intravenous routes in 2 species of nonhuman primates. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002;185:1668-1771.1. Purcell RH. Relative infectivity of hepatitis A virus by the oral and intravenous routes in 2 species of nonhuman primates. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002;185:1668-1771.

2. Tassopoulos NC, Papaevangelou GJ, Ticehurst JR, Purcell RH. Fecal excretion of Greek strains of hepatitis A virus in patients with hepatitis A and in experimentally infected chimpanzees. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1986;154(2):231-237.

3. Fiore AE. Hepatitis A transmitted by food. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004;38(5):705-715.

4. Carl M, Francis DP, Maynard JE. Food-borne hepatitis A: recommendations for control. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1983;148(6):1133-1135.

5. Millard J, Appleton H, Parry JV. Studies on heat inactivation of hepatitis A virus with special reference to shellfish. Part 1. Procedures for infection and recovery of virus from laboratory-maintained cockles. Epidemiol Infect. 1987;98(3):397-414.

6. Halliday ML, Kang LY, Zhou TK, et al. An epidemic of hepatitis A attributable to the ingestion of raw clams in Shanghai, China. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1991;164(5):852-859.

7. Hadler SC, Webster HM, Erben JJ, Swanson JE, Maynard JE. Hepatitis A in day-care centers. A community-wide assessment. The New England journal of medicine. 1980;302(22):1222-1227.

8. Lednar WM, Lemon SM, Kirkpatrick JW, Redfield RR, Fields ML, Kelley PW. Frequency of illness associated with epidemic hepatitis A virus infections in adults. American journal of epidemiology. 1985;122(2):226-233.

9. Tong MJ, el-Farra NS, Grew MI. Clinical manifestations of hepatitis A: recent experience in a community teaching hospital. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1995;171 Suppl 1:S15-18.

10. Koff RS. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of hepatitis A virus infection. Vaccine. 1992;10 Suppl 1:S15-17.

11. Sjogren MH, Tanno H, Fay O, et al. Hepatitis A virus in stool during clinical relapse. Annals of internal medicine. 1987;106(2):221-226.

12. Gordon SC, Reddy KR, Schiff L, Schiff ER. Prolonged intrahepatic cholestasis secondary to acute hepatitis A. Annals of internal medicine. 1984;101(5):635-637.

13. Schiff ER. Atypical clinical manifestations of hepatitis A. Vaccine. 1992;10 Suppl 1:S18-20.

14. Neefe JR, Gellis SS, Stokes J, Jr. Homologous serum hepatitis and infectious (epidemic) hepatitis; studies in volunteers bearing on immunological and other characteristics of the etiological agents. The American journal of medicine. 1946;1:3-22.

15. Krugman S, Giles JP, Hammond J. Infectious hepatitis. Evidence for two distinctive clinical, epidemiological, and immunological types of infection. Jama. 1967;200(5):365-373.

16. Griffin DW, Donaldson KA, Paul JH, Rose JB. Pathogenic human viruses in coastal waters. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2003;16(1):129-143.

17. Murphy P, Nowak T, Lemon SM, Hilfenhaus J. Inactivation of hepatitis A virus by heat treatment in aqueous solution. J Med Virol. 1993;41(1):61-64.

18. Peterson DA, Hurley TR, Hoff JC, Wolfe LG. Effect of chlorine treatment on infectivity of hepatitis A virus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45(1):223-227.

19. Plumb ID, Bulkow LR, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, Morris J, Rudolph K, Spradling P, Snowball M, McMahon BJ. Persistence of antibody to Hepatitis A virus 20 years after receipt of Hepatitis A vaccine in Alaska. J Viral Hepat. 2017 Jul;24(7):608-612.

20. Theeten H, Van Herck K, Van Der Meeren O, Crasta P, Van Damme P, Hens N. Long-term antibody persistence after vaccination with a 2-dose Havrix™ (inactivated hepatitis A vaccine): 20 years of observed data, and long-term model-based predictions. Vaccine. 2015 Oct 13;33(42):5723-7.

21. Hens N, Habteab Ghebretinsae A, Hardt K, Van Damme P, Van Herck K. Model based estimates of long-term persistence of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine-induced antibodies in adults. Vaccine. 2014;32(13):1507-1513.

22. Clemens R, Safary A, Hepburn A, Roche C, Stanbury WJ, Andre FE. Clinical experience with an inactivated hepatitis A vaccine. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1995;171 Suppl 1:S44-49.

23. Ambrosch F, Andre FE, Delem A, et al. Simultaneous vaccination against hepatitis A and B: results of a controlled study. Vaccine. 1992;10 Suppl 1:S142-145.

24. Gil A, Gonzalez A, Dal-Re R, Calero JR. Interference assessment of yellow fever vaccine with the immune response to a single-dose inactivated hepatitis A vaccine (1440 EL.U.). A controlled study in adults. Vaccine. 1996;14(11):1028-1030.

25. Jong EC, Kaplan KM, Eves KA, Taddeo CA, Lakkis HD, Kuter BJ. An open randomized study of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine administered concomitantly with typhoid fever and yellow fever vaccines. Journal of travel medicine. 2002;9(2):66-70.

26. Nolan T, Bernstein H, Blatter MM, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated hepatitis A vaccine administered concomitantly with diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis and haemophilus influenzae type B vaccines to children less than 2 years of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e602-609.

27. Usonis V, Meriste S, Bakasenas V, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine administered concomitantly with either a measles-mumps-rubella or a diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-inactivated poliomyelitis vaccine mixed with a Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in infants aged 12-18 months. Vaccine. 2005;23(20):2602-2606.

28. Bryan JP, Henry CH, Hoffman AG, et al. Randomized, cross-over, controlled comparison of two inactivated hepatitis A vaccines. Vaccine. 2000;19(7-8):743-750.

29. Connor BA, Phair J, Sack D, et al. Randomized, double-blind study in healthy adults to assess the boosting effect of Vaqta or Havrix after a single dose of Havrix. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001;32(3):396-401.

30. Letson GW, Shapiro CN, Kuehn D, et al. Effect of maternal antibody on immunogenicity of hepatitis A vaccine in infants. J Pediatr 2004;144:327–32.

31. Dagan R, Amir J, Mijalovsky A, et al. Immunization against hepatitis A in the first year of life: priming despite the presence of maternal antibody. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:1045–52.

32. Moro PL, Museru OI, Niu M, Lewis P, Broder K. Reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System after hepatitis A and hepatitis AB vaccines in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;210(6):561.e1-6.

33. Ott JJ, Wiersma ST. Single-dose administration of inactivated hepatitis A vaccination in the context of hepatitis A vaccine recommendations. Int J Infect Dis. 2013 Nov;17(11):e939-44.

34. Bryan JP, Nelson M. Testing for antibody to hepatitis A to decrease the cost of hepatitis A prophylaxis with immune globulin or hepatitis A vaccines. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:663–8.

35. Tejada-Strop A, Costafreda MI, Dimitrova Z, Kaplan GG, Teo CG. Evaluation of potencies of immune globulin products against hepatitis A. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:430–2.

- Page last reviewed: October 3, 2017

- Page last updated: October 3, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir