Clinical Guidance

Dengue Virus

Dengue infection is caused by any one of four distinct but closely related dengue virus (DENV) serotypes (called DENV-1, -2, -3, and -4). These dengue viruses are single-stranded RNA viruses that belong to the family Flaviviridae and the genus Flavivirus—a family which includes other medically important vector-borne viruses (e.g., West Nile virus, Yellow Fever virus, Japanese Encephalitis virus, St. Louis Encephalitis virus, etc.). Dengue viruses are arboviruses (arthropod-borne virus) that are transmitted primarily to humans through the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito. Transmission may also occur through transfusion of infected blood or transplantation of infected organs or tissues. Human transmission of dengue is also known to occur after occupational exposure in healthcare settings (e.g., needle stick injuries) and cases of vertical transmission have been described in the literature (i.e., transmission from a dengue infected pregnant mother to her fetus in utero or to her infant during labor and delivery).

Clinical Dengue

Infection with any of the four dengue serotypes can produce the full spectrum of illness and severity. The spectrum of illness can range from a mild, non-specific febrile syndrome to classic dengue fever (DF), to the severe forms of the disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS). Severe forms typically manifest after a two to seven day febrile phase and are often heralded by clinical and laboratory warning signs. Early clinical recognition of dengue infection and anticipatory treatment for those who develop DHF or DSS can save lives. While no therapeutic agents exist for dengue infections, the key to the successful management is timely and judicious use of supportive care, including administration of isotonic intravenous fluids or colloids, and close monitoring of vital signs and hemodynamic status, fluid balance, and hematologic parameters. (Recommended therapies and treatment courses for DF, DHF and DSS can be found at the links provided below.)

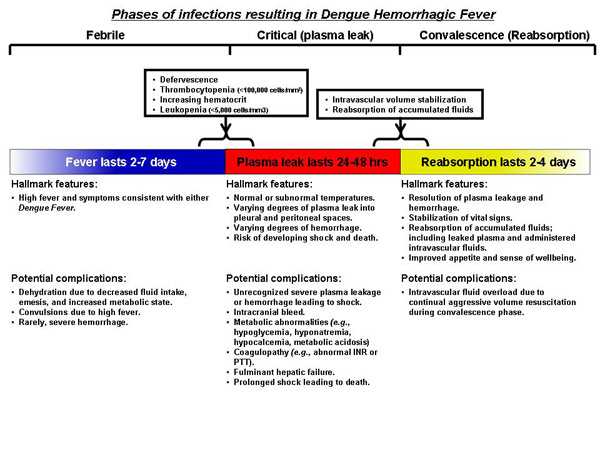

As the early presentations of DF and DHF/DSS are similar and the course of infection is short, timely identification of persons that will develop severe manifestations can be challenging. There is a long-standing debate as to whether DHF/DSS represents a separate pathophysiological process or is merely the opposite end of a continuum of the same illness. DF follows an uncomfortable but relatively benign self-limited course. DHF may appear as a relatively benign infection at first but can quickly develop into life-threatening illness as fever abates. DHF can usually be distinguished from DF as it progresses through its three predictable pathophysiological phases:

- Febrile phase: Viremia-driven high fevers

- Critical/plasma leak phase: Sudden onset of varying degrees of plasma leak into the pleural and abdominal cavities

- Convalescence or reabsorption phase: Sudden arrest of plasma leak with concomitant reabsorption of extravasated plasma and fluids

For optimal management of the patient with dengue infection, it is important to understand these phases and to be able to distinguish DHF from DF. Early recognition of a patient’s clinical phase is important in order to tailor clinical management, monitor effectiveness of the treatment, and to anticipate when changes in their management are needed.

Dengue infected patients are either asymptomatic or they have one of three clinical presentations:

- Undifferentiated Fever;

- Dengue Fever with or without hemorrhage; or

- Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever or Dengue Shock Syndrome.

Asymptomatic Infection: As many as one half of all dengue infected individuals are asymptomatic, that is, they have no clinical signs or symptoms of disease.

Undifferentiated Fever: The first clinical course is a relatively benign scenario where the patient experiences fever with mild non-specific symptoms that can mimic any number of other acute febrile illnesses. They do not meet case definition criteria for DF. The non-specific presentation of symptoms make positive diagnosis difficult based on physical exam and routine tests alone. For the majority of these patients, unless dengue diagnostic serological or molecular testing is performed, the diagnosis will remain unknown. These patients are typically young children or those experiencing their first infection, and they recover fully without need for hospital care.

Dengue Fever with or without hemorrhage: The second clinical presentation occurs when a patient develops DF with or without hemorrhage. These patients are typically older children or adults and they present with two to seven days of high fever (occasionally biphasic) and two or more of the following symptoms: severe headache, retro-orbital eye pain, myalgias, arthralgias, a diffuse erythematous maculo-papular rash, and mild hemorrhagic manifestation. Subtle, minor epithelial hemorrhage, in the form of petechiae, are often found on the lower extremities (but may occur on buccal mucosa, hard and soft palates and or subconjunctivae as well), easy bruising on the skin, or the patient may have a positive tourniquet test. Other forms of hemorrhage such as epistaxis, gingival bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, or urogenital bleeding can also occur, but are rare. Leukopenia is frequently found and may be accompanied by varying degrees of thrombocytopenia. Children may also present with nausea and vomiting. Patients with DF do not develop substantial plasma leak (hallmark of DHF and DSS, see below) or extensive clinical hemorrhage. Serological testing for anti-dengue IgM antibodies or molecular testing for dengue viral RNA or viral isolation can confirm the diagnosis, but these tests often provide only retrospective confirmation, as results are typically not available until well after the patient has recovered.

Clinical presentation of DF and the early phase of DHF are similar, and therefore it can be difficult to differentiate between the two forms early in the course of illness. With close monitoring of key indicators, the development of DHF can be detected at the time of defervescence so that early and appropriate therapy can be initiated. The key to successfully managing patients with dengue infection and lowering the probability of medical complications or death due to DHF or DSS is early recognition and anticipatory treatment. (For more detailed guidance on management for DF please see the recommended treatment courses for DHF in the links listed below.)

Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF) or Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS): The third clinical presentation results in the development of DHF, which in some patients progresses to DSS. Vigilant is critical for identifying warning signs of progressing illness and early symptoms of DHF which are very similar to those of DF. Case Definitions Page

There are three phases of DHF: the Febrile Phase ; the Critical (Plasma Leak) Phase; and the Convalescent (Reabsorption) Phase.

The Febrile Phase: Early in the course of illness, patients with DHF can present much like DF, but they may also have hepatomegaly without jaundice (later in the Febrile Phase). The hemorrhagic manifestations that occur in the early course of DHF most frequently consist of mild hemorrhagic manifestations as in DF. Less commonly, epistaxis, bleeding of the gums, or frank gastrointestinal bleeding occur while the patient is still febrile (gastrointestinal bleeding may commence at this point, but commonly does not become apparent until a melenic stool is passed much later in the course). Dengue viremia is typically highest in the first three to four days after onset of fever but then falls quickly to undetectable levels over the next few days. The level of viremia and fever usually follow each other closely, and anti-dengue IgM anti-bodies increase as fever abates.

The Critical (Plasma Leak) Phase: About the time when the fever abates, the patient enters a period of highest risk for developing the severe manifestations of plasma leak and hemorrhage. At this time, it is vital to watch for evidence of hemorrhage and plasma leak into the pleural and abdominal cavities and to implement appropriate therapies replacing intravascular losses and stabilizing effective volume. If left untreated, this can lead to intravascular volume depletion and cardiovascular compromise. Evidence of plasma leak includes sudden increase in hematocrit (≥20% increase from baseline), presence of ascites, a new pleural effusion on lateral decubitus chest x-ray, or low serum albumin or protein for age and sex. Patients with plasma leak should be monitored for early changes in hemodynamic parameters consistent with compensated shock such as increased heart rate (tachycardia) for age especially in the absence of fever, weak and thready pulse, cool extremities, narrowing pulse pressure (systolic blood pressure minus diastolic blood pressure <20 mmHg), delayed capillary refill (>2 seconds), and decrease in urination (i.e., oliguria). Patients exhibiting signs of increasing intravascular depletion, impending or frank shock, or severe hemorrhage should be admitted to an appropriate level intensive care unit for monitoring and intravascular volume replacement. Once a patient experiences frank shock he or she will be categorized as having DSS. Prolonged shock is the main factor associated with complications that can lead to death including massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Interestingly, many patients with DHF/DSS remain alert and lucid throughout the course of the illness, even at the tipping point of profound shock. See case definition for DHF and DSS [PDF – 1 page].

Warning signs that may occur at or after defervescence (the presence of one or more of these signs indicates the need for immediate medical evaluation)

- Abdominal pain or tenderness

- Persistent vomiting

- Clinical fluid accumulation (i.e., pleural effusion or ascites)

- Mucosal bleeding

- Lethargy or restlessness

- Liver enlargement (≥2cm)

- Increases in hematocrit concurrent with rapid decrease in platelet count

Anticipatory management and monitoring indicators are essential in effectively administering therapies as the patient enters the Critical Phase. New-onset leucopenia (WBC <5,000 cells/mm3) with a lymphocytosis and an increase in atypical lymphocytes indicate that the fever will likely dissipate within the next 24 hours and that the patient is entering into the Critical Phase. Indicators that suggest the patient has already entered the Critical Phase include sudden change from high (>38.0°C) to normal or subnormal temperatures, thrombocytopenia (≤100,000 cells/mm3) with a rising or elevated hematocrit (≥20% increase from baseline), new hypoalbuminemia or hypocholesterolemia, new pleural effusion or ascites, and signs and symptoms of impending or frank shock.

Again, the key to successfully managing patients with DHF and lowering the probability of complications or death is early recognition and anticipatory treatment. Supportive care and timely but measured intravascular volume replacement during the Critical Period are the mainstays of treatment for DHF and DSS. (For more detailed guidance on management guidance, please see the recommended treatment courses for DHF in the links listed below link.) Fortunately, the Critical Period lasts no more than 24 to 48 hours. Most of the complications that arise during this period—such as hemorrhage and metabolic abnormalities (e.g., hypocalcemia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, lactic acidosis, and hyponatremia) are frequently related to prolonged shock. Hence, the principal objective during this period is to prevent prolonged shock and support vital systems until plasma leak subsides. Careful attention must be paid to the type of intravenous fluid (or blood product if transfusion is needed) administered, the rate, and the volume received over time. Frequent monitoring of intravascular volume, vital organ function, and the patient’s response are essential for successful management during the Critical Phase. Monitoring for overt and occult hemorrhage (which may be another source of intravascular depletion) is also important. Transfusion of volume-replacing blood products should be considered if substantial hemorrhage is suspected during this phase. (For more detailed guidance on management, please see the recommended treatment courses for DHF in the links listed below.)

The Convalescent (Reabsorption) Phase: The third phase begins when the Critical Phase ends and is characterized when plasma leak stops and reabsorption begins. During this phase, fluids that leaked from the intravascular space (i.e., plasma and administered intravenous fluids) during the Critical Phase are reabsorbed. Indicators suggesting that the patient is entering the Convalescent Phase include sense of improved well being reported by the patient, return of appetite, stabilizing vital signs (widen pulse pressure, strong palpable pulse), bradycardia, hematocrit levels returning to normal, increased urine output, and appearance of the characteristic Convalescence Rash of Dengue (i.e., a confluent sometimes pruritic, petechial rash with multiple small round islands of unaffected skin). At this point, care must be taken to recognize signs indicating that the intravascular volume has stabilized (i.e., that plasma leak has halted) and that reabsorption has begun. Modifying the rate and volume of intravenous fluids (and often times discontinuing intravenous fluids altogether) to avoid fluid overload as the extravasated fluids return to the intravascular compartment is important. Complications that arise during Convalescent (Reabsorption) Phase are frequently related to the intravenous fluid management. Fluid overload may result from use of hypotonic intravenous fluids or over use or continued use of isotonic intravenous fluids during the Convalescence Phase… (For more detailed guidance on management please see the recommended treatment courses for DHF in the links listed below.)

Although an infected patient will likely have been very uncomfortable (from eye, joint, bone, muscle, or head pain) during the illness, barring complications such as fluid overload or mechanical ventilation nearly all patients with DHF recover rapidly with timely initiation of judicious fluid management and careful monitoring. This is due to the fact that the period of increased vascular permeability is time-limited (lasting 24 to 48 hours) and the functional change in the vascular endothelium appears to be entirely reversible with no known permanent structural defect. Even those with complications, if managed successfully, often recover fully without sequelae.

Clinical guidelines for the management of dengue infection

Clinical management tools for health care providers

Requesting dengue laboratory testing and case reporting

Patient educational materials

- Page last reviewed: September 9, 2009

- Page last updated: September 6, 2014

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir