Vel blood group

The Vel blood group is a human blood group that has been implicated in hemolytic transfusion reactions.[1] The blood group consists of a single antigen, the high-frequency Vel antigen, which is expressed on the surface of red blood cells. Individuals are typed as Vel-positive or Vel-negative depending on the presence of this antigen. The expression of the antigen in Vel-positive individuals is highly variable and can range from strong to weak. Individuals with the rare Vel-negative blood type develop anti-Vel antibodies when exposed to Vel-positive blood, which can cause transfusion reactions on subsequent exposures.[2]

| Small integral membrane protein 1 (Vel blood group antigen) | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | SMIM1 |

| HGNC | 44204 |

| OMIM | 615242 |

| RefSeq | 388588 |

| UniProt | B2RUZ4 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 1 p36.32 |

Genetics

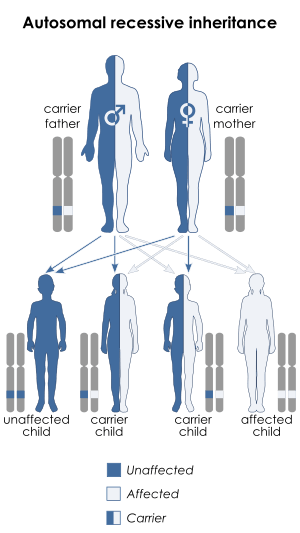

The Vel blood group is associated with the SMIM1 gene, which is located in the 1p36 region of chromosome 1. This gene produces small integral membrane protein 1, a single-pass transmembrane protein which carries the Vel antigen[2] but whose structure and function are otherwise poorly understood.[3] The Vel-negative phenotype is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, being expressed by patients who are homozygous for a deletion mutation in the coding region of SMIM1 which renders the gene nonfunctional.[3][4] Patients who are heterozygous for this mutation, meaning inherited from only one parent, exhibit weakened Vel antigen expression.[5] Missense mutations at nucleotide position 152 can also result in a weak Vel phenotype, and various single nucleotide polymorphisms in the noncoding regions of SMIM1 affect the strength of Vel antigen expression.[3]

Epidemiology

The Vel-negative blood type is rare. The highest prevalence of Vel-negative blood has been reported in Sweden, where approximately 1 in 1200 individuals exhibit this phenotype.[3] Only about 1 in 3000 English people[6] and 1 in 4000 Southern Europeans are Vel-negative, and much lower rates have been reported in people of African and Asian heritage.[3]

Clinical significance

When exposed to Vel-positive blood through transfusion or pregnancy, Vel-negative individuals can become sensitized and begin producing an anti-Vel antibody. If they are exposed to Vel-positive blood again, the anti-Vel antibody can bind to Vel-positive red blood cells and destroy them, causing hemolysis.[2][7]:696 Anti-Vel is a particularly dangerous antibody because it is able to activate the complement system, which causes immediate and severe destruction of red blood cells.[8][9] Therefore, patients with anti-Vel should not be transfused with Vel-positive blood, as it can cause a serious acute hemolytic transfusion reaction.[2][6] Finding compatible blood for Vel-negative patients is difficult due to the rarity of this blood type,[3] and it may be necessary to perform autologous blood donation or to contact rare blood banks.[10]

Cases of anti-Vel causing hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) have been reported, but this is an unusual occurrence.[3][6] It is hypothesized that anti-Vel associated HDN is rare because the antibody is usually predominantly composed of IgM immunoglobulin, which does not cross the placenta into the fetal circulation.[7]:981 In addition, the expression of Vel is very weak on fetal red blood cells – particularly in children who are heterozygous for Vel.[6]

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (a condition in which patients produce antibodies against antigens on their own red blood cells, leading to hemolysis)[7]:956 involving auto-anti-Vel has been reported.[6]

Laboratory testing

An individual's Vel blood type can be determined by serologic methods, which use reagents containing anti-Vel antibodies to identify the antigen, or by genetic testing.[3] As of 2019, serologic testing for Vel is mainly performed using polyclonal antibodies isolated from the blood of patients with anti-Vel. However, this method is problematic because these antibodies are variable in quality and sometimes produce false negative results in patients with weak Vel expression; moreover, the reagent cannot be mass produced.[3][11] In 2016, a recombinant monoclonal antibody against Vel was introduced[12] and it has since been used to screen for Vel-negative blood donors in France.[3] Genotyping of SMIM1 using polymerase chain reaction is another method that has been used to identify Vel-negative donors.[13]

Anti-Vel is a mixture of IgG and IgM immunoglobulins and is able to activate complement, which can cause hemolysis in vitro (i.e. during compatibility testing).[3][14] Anti-Vel can be mistaken for a typical cold antibody in compatibility testing if inappropriate techniques are used; this misidentification is dangerous, because such antibodies are usually clinically insignificant.[3][10][15]

History

The Vel blood group was first described in 1952 by Sussman and Miller,[16] who reported a case of a patient who had suffered a severe hemolytic reaction following a blood transfusion.[2] The patient's serum was subsequently crossmatched against blood samples from 10,000 donors, and only five of them were found to be compatible, indicating that an antibody against a high-frequency antigen was present.[3] This antigen was named Vel after the first patient.[1] The authors also observed variable expression of the antigen: the patient's serum reacted less strongly with the blood of her children, who were presumably heterozygous for Vel, than with blood from unrelated donors.[3]

In 1955, a further case was described [17] in which the blood of a woman who had suffered a transfusion reaction was incompatible with more than 1,000 donors, but not with the blood of the first Vel-negative patient.[3] This patient's antibody was the first example of an anti-Vel that could hemolyze red blood cells in vitro.[18] Six other individuals from three generations of this woman's family were found to be Vel-negative, but they did not exhibit an anti-Vel antibody, demonstrating that anti-Vel is not naturally occurring.[2] By 1962, 19 cases of anti-Vel and approximately 50 cases of Vel-negative patients had been described.[18]

Although the Vel blood group has been widely studied due to its significance in transfusion medicine, its genetic and molecular basis remained unclear for several decades.[10][12] In 2013, two research groups simultaneously identified the SMIM1 gene and its protein product as the determinants of the Vel blood group.[10][19][20] The Vel blood group was officially recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion in 2016.[5]

References

- Harmening D (10 July 2012). "Part II: Blood groups and serologic testing". Modern Blood Banking and Transfusion Practices (6th ed.). F.A. Davis. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-8036-3793-1.

- Kniffin CL (2013-05-30). "OMIM Entry # 615264 - BLOOD GROUP, VEL SYSTEM; VEL". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- Storry JR, Peyrard T (June 2017). "The Vel blood group system: a review" (PDF). Immunohematology. 33 (2): 56–59. PMID 28657763.

- Storry JR, Jöud M, Christophersen MK, Thuresson B, Åkerström B, Sojka BN, et al. (May 2013). "Homozygosity for a null allele of SMIM1 defines the Vel-negative blood group phenotype" (PDF). Nature Genetics. 45 (5): 537–41. doi:10.1038/ng.2600. PMID 23563606.

- Storry JR, Castilho L, Chen Q, Daniels G, Denomme G, Flegel WA, et al. (August 2016). "International society of blood transfusion working party on red cell immunogenetics and terminology: report of the Seoul and London meetings". ISBT Science Series. 11 (2): 118–122. doi:10.1111/voxs.12280. PMC 5662010. PMID 29093749.

- Daniels G (2013). "Chapter 30: High frequency antigens, including Vel". Human Blood Groups (3rd ed.). West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 601–2. ISBN 978-1-118-49354-0.

- Greer JP, Perkins SL (December 2008). Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology. 1 (12th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-6507-7.

- Daniels G, Bromilow I (2011). "Other blood groups". Essential Guide to Blood Groups (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4443-9617-1.

- Rudmann SV (2005). "Section 2: Blood group serology". Textbook of Blood Banking and Transfusion Medicine (2nd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7216-0384-1.

- Ballif BA, Helias V, Peyrard T, Menanteau C, Saison C, Lucien N, et al. (May 2013). "Disruption of SMIM1 causes the Vel- blood type". EMBO Molecular Medicine. 5 (5): 751–61. doi:10.1002/emmm.201302466. PMC 3662317. PMID 23505126.

- van der Rijst MV, Lissenberg-Thunnissen SN, Ligthart PC, Visser R, Jongerius JM, Voorn L, et al. (April 2019). "Development of a recombinant anti-Vel immunoglobulin M to identify Vel-negative donors". Transfusion. 59 (4): 1359–1366. doi:10.1111/trf.15147. PMID 30702752.

- Danger Y, Danard S, Gringoire V, Peyrard T, Riou P, Semana G, Vérité F (February 2016). "Characterization of a new human monoclonal antibody directed against the Vel antigen". Vox Sanguinis. 110 (2): 172–8. doi:10.1111/vox.12321. PMID 26382919.

- Wieckhusen C, Rink G, Scharberg EA, Rothenberger S, Kömürcü N, Bugert P (November 2015). "Molecular Screening for Vel- Blood Donors in Southwestern Germany". Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 42 (6): 356–60. doi:10.1159/000440791. PMC 4698648. PMID 26732700.

- Reid ME, Lomas-Francis C (8 September 2003). "The 901 series of high incidence antigens". The Blood Group Antigen FactsBook (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 504. ISBN 978-0-08-047615-5.

- Storry JR, Mallory D (1994). "Misidentification of anti-Vel due to inappropriate use of prewarming and adsorption techniques". Immunohematology. 10 (3): 83–6. PMID 15945800.

- Sussman LN, Miller EB (1952). "[New blood factor: Vel]". Revue d'Hématologie. 7 (3): 368–71. PMID 13004554.

- Levine P, Robinson EA, Herrington LB, Sussman LN (July 1955). "Second example of the antibody for the high-incidence blood factor Vel". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 25 (7): 751–4. doi:10.1093/ajcp/25.7.751. PMID 14387975.

- Sussman LN (1962). "Current status of the Vel blood group system". Transfusion. 2 (3): 163–71. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.1962.tb00216.x. PMID 13918506.

- Storry JR (2014). "Five new blood group systems - what next?". ISBT Science Series. 9 (1): 136–140. doi:10.1111/voxs.12078. ISSN 1751-2816.

- Cvejic A, Haer-Wigman L, Stephens JC, Kostadima M, Smethurst PA, Frontini M, et al. (May 2013). "SMIM1 underlies the Vel blood group and influences red blood cell traits". Nature Genetics. 45 (5): 542–545. doi:10.1038/ng.2603. PMC 4179282. PMID 23563608.