Gastric glands

The gastric glands are located in different regions of the stomach. These are the fundic glands, the cardiac glands, and the pyloric glands. The glands and gastric pits are located in the stomach lining. The glands themselves are in the lamina propria of the mucous membrane and they open into the bases of the gastric pits formed by the epithelium.[1] The various cells of the glands secrete mucus, pepsinogen, hydrochloric acid, intrinsic factor, gastrin, and bicarbonate.

| Gastric glands | |

|---|---|

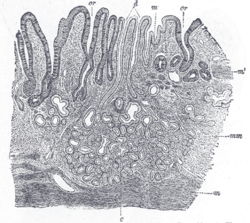

Cardiac glands shown at c and their ducts at d | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandulae gastricae |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Types of gland

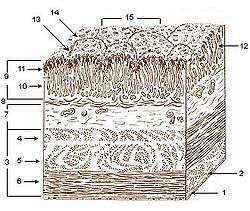

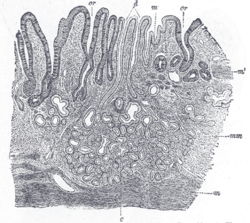

The three types of gland are all located beneath the gastric pits within the gastric mucosa–the mucous membrane of the stomach. The gastric mucosa is pitted with innumerable gastric pits which each house 3-5 gastric glands[2][3].

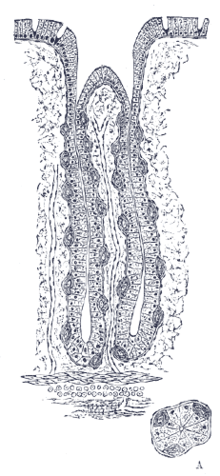

The cardiac glands are found in the cardia of the stomach which is the part nearest to the heart, enclosing the opening where the esophagus joins to the stomach. Only cardiac glands are found here and they primarily secrete mucus.[4] They are fewer in number than the other gastric glands and are more shallowly positioned in the mucosa. There are two kinds - either simple tubular with short ducts or compound racemose resembling the duodenal Brunner's glands.

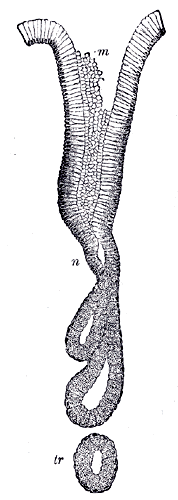

The fundic glands (or oxyntic glands), are found in the fundus and body of the stomach. They are simple almost straight tubes, two or more of which open into a single duct. Oxyntic means acid-secreting and they secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) and intrinsic factor.[4]

The pyloric glands are located in the antrum of the pylorus. They secrete gastrin produced by their G cells.[5]

| Layer of stomach | Name | Secretion | Region of stomach | Staining |

| Isthmus of gland | Foveolar cells | Mucus gel layer | Fundic, cardiac, pyloric | Clear |

| Body of gland | Parietal (oxyntic) cells | Gastric acid and intrinsic factor | Fundic only | Acidophilic |

| Base of gland | Chief (zymogenic) cells | Pepsinogen and gastric lipase | Fundic only | Basophilic |

| Base of gland | Enteroendocrine (APUD) cells | Hormones gastrin, histamine, endorphins, serotonin, cholecystokinin and somatostatin | Fundic, cardiac, pyloric | – |

Types of cell

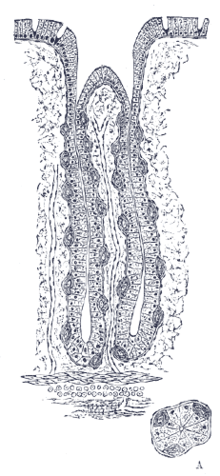

There are millions of gastric pits in the gastric mucosa and their necessary narrowness determines the tubular form of the gastric gland. More than one tube allows for the accommodation of more than one cell type. The form of each gastric gland is similar; they are all described as having a neck region that is closest to the pit entrance, and basal regions on the lower parts of the tubes.[6] The epithelium from the gastric mucosa travels into the pit and at the neck the epithelial cells change to short columnar granular cells. These cells almost fill the tube and the remaining lumen is continued as a very fine channel.

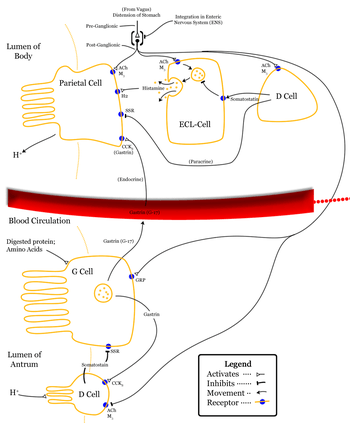

Cells found in the gastric glands include foveolar cells, chief cells, parietal cells, G cells and enterochromaffin-like cells (ECLs). The first cells of all of the glands are foveolar cells in the neck region–also called mucous neck cells that produce mucus. This is thought to be different from the mucus produced by the gastric mucosa.

Fundic glands found in the fundus and also in the body have another two cell types–gastric chief cells and parietal cells (oxyntic)).

The chief cells are found in the basal regions of the gland and release a zymogen – pepsinogen, a precursor to pepsin.[7]

The parietal cells ("parietal" means "relating to a wall") are found in the walls of the tubes. The parietal cells secrete hydrochloric acid–the main component of gastric acid. This needs to be readily available for the stomach in a plentiful supply, and so from their positions in the walls, their secretory networks of fine channels called canaliculi can project and ingress into all the regions of the gastric-pit lumen. Another important secretion of the parietal cells is intrinsic factor. Intrinsic factor is a glycoprotein essential for the absorption of vitamin B12.

The parietal cells also produce and release bicarbonate ions in response to histamine release from the nearby ECLs, and so serve a crucial role in the pH buffering system.[8]

The enterochromaffin-like cells store and release histamine when the pH of the stomach becomes too high. The release of histamine is stimulated by the secretion of gastrin from the G cells.[9] Histamine promotes the production and release of HCL from the parietal cells to the blood and protons to the stomach lumen. When the stomach pH decreases(becomes more acidic), the ECLs stop releasing histamine.

The G cells are mostly found in pyloric glands in the antrum of the pylorus; some are found in the duodenum and other tissues. The G cells secrete gastrin. The gastric pits of these glands are much deeper than the others and here the gastrin is secreted into the bloodstream not the lumen.[10]

Clinical significance

Fundic gland polyposis is a medical syndrome where the fundus and the body of the stomach develops many polyps.

Pernicious anemia is caused when damaged parietal cells fail to produce the intrinsic factor necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12. This can be one of the causes of vitamin B12 deficiency.

See also

Additional images

Layers of stomach wall

Layers of stomach wall Gastric acid regulation

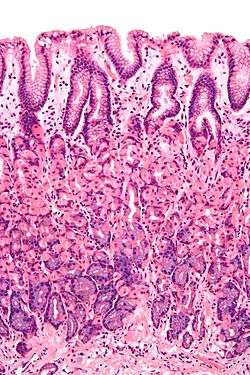

Gastric acid regulation Human cardiac glands (at cardia)

Human cardiac glands (at cardia) Human pyloric glands (at pylorus)

Human pyloric glands (at pylorus) Human fundic glands (at fundus)

Human fundic glands (at fundus)

References

- "Stomach". Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "gastric pits, that each open into four or five gastric glands", Quantitative Human Physiology 2E, 2017, Joseph Feher

- "Secretions from several gastric glands flow into each gastric pit" Principals of Anatomy & Physiology 15th Ed 2017, Gerard Tortora & Bryan Derrickson

- Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 777. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 762. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- Pocock, Gillian (2006). Human Physiology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- Khan, AR; James, MN (April 1998). "Molecular mechanisms for the conversion of zymogens to active proteolytic enzymes". Protein Science. 7 (4): 815–36. doi:10.1002/pro.5560070401. PMC 2143990. PMID 9568890.

- "Clinical correlates of pH levels: bicarbonate as a buffer". Biology.arizona.edu. October 2006.

- Guyton, Arthur C.; John E. Hall (2006). Textbook of Medical Physiology (11 ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. p. 797. ISBN 0-7216-0240-1.

- "Basic organization of the gastrointestinal tract". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

- Histology image: 50_02 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center - "Fundic stomach"

- Anatomy photo: Digestive/mammal/stomach4/stomach2 - Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis - "Mammal, ruminant stomach (LM, High)"

- Histology image: 11301ooa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Digestive System: Alimentary Canal - fundic stomach"

- Veterinary Histology at vt.edu

- MedEd at Loyola Histo/frames/Histo18.html - see slide #42

- Histology image: 100_04 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center - "Esophageal-stomach junction"

- Histology image: 11103loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Digestive System: Alimentary Canal: esophageal/stomach junction"