Healthcare in South Africa

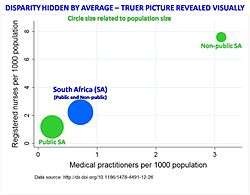

In South Africa, private and public health systems exist in parallel. The public system serves the vast majority of the population, but is chronically underfunded and understaffed. The wealthiest 20% of the population use the private system and are far better served. In 2005, South Africa spent 8.7% of GDP on health care, or US$437 per capita. Of that, approximately 42% was government expenditure.[1] About 79% of doctors work in the private sector.[2] It has the highest levels of obesity in sub-Saharan Africa.[3]

History

The first hospital in South Africa, a temporary tent to care for sick sailors of the Dutch East India Company (the Company) afflicted by diseases such as typhoid and scurvy, was started at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.[4]

A permanent hospital was completed in 1656. Initially, convalescent soldiers provided to others whatever care they could, but around 1700 the first Binnenmoeder (Dutch for matron) and Siekenvader (male nurse/supervisor) were appointed in order to ensure cleanliness in the hospital, and to supervise bedside attendants.[4]

The Company subsequently employed Sworn Midwives from Holland, who practiced midwifery and also trained and examined local women who wished to become midwives. Some of the early trainees at the Cape were freed Malay and coloured slaves.[4]

From 1807, other hospitals were built in order to meet the increasing demand for healthcare. The first hospitals in the Eastern Cape were founded in Port Elizabeth, King Williamstown, Grahamstown and Queenstown.[4]

Missionary hospitals

Roman Catholic Nuns of the Assumption Order were the first members of a religious order to arrive in South Africa. In 1874, two Nightingale nurses, Anglican Sisterhoods, the Community of St Michael and All Angels arrived from England.[4]

The discovery of diamonds in Kimberley led to an explosion of immigrants, which, coupled with the "generally squalid conditions" around mines, encouraged the spread of diseases dysentery, typhoid, and malaria.[4]

Following negotiations with the Anglican Order of St Michael, Sister Henrietta Stockdale and other members were assigned to the Carnarvon hospital in 1877. Sister Stockdale had studied nursing and taught the nurses at Carnavorn what she knew; these nurses would move to other hospitals in Barbeton, Pretoria, Queenstown, and Cape Town, where they in turn trained others in nursing. This laid the foundation of professional nursing in South Africa.[4]

Sister Stockdale was also responsible for the nursing clauses in the Cape of Good Hope Medical and Pharmacy Act of 1891, the world's first regulations requiring state registration of nurses.[4]

Most mission hospitals have become public hospitals in contemporary South Africa.[4]

20th-century nursing

The Anglo-Boer war and World War 1 severely strained healthcare provision in South Africa.[4]

Formal training for black nurses began at Lovedale in 1902. In the first half of the 20th century, nursing was not considered appropriate for Indian women but some males did become registered nurses or orderlies.[4]

In 1912, the South African military recognised the importance of military nursing in the Defence Act. In 1913, the first nursing journal, The South African Nursing Record, was published. In 1914, The South African Trained Nurses' Association, the first organisation for nurses, formed. In 1944, the first Nursing Act was promulgated.[4]

In 1935, the first diploma courses to enable nurses to train as tutors were introduced at the University of Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town.[4]

The establishment of independent states and homelands in South Africa also created independent Nursing Councils, and Nursing Associations for the Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, and Ciskei. Under the post-Apartheid dispensation, these were all merged to form one organisation, the Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa (DENOSA).[4]

Health infrastructure

Staffing

In 2013, it was estimated that vacancy rates for doctors were 56% and for nurses 46%. Half the population lives in rural areas, but only 3% of newly qualified doctors take jobs there. All medical training takes place in the public sector but 70% of doctors go into the private sector. 10% of medical staff are qualified in other countries. Medical student numbers increased by 34% between 2000 and 2012.[5]

| Province | People-to-doctor ratio | People-to-nurse ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Cape | 4 280 to 1 | 673 to 1 |

| Free State | 5 228 to 1 | 1 198 to 1 |

| Gauteng | 4 024 to 1 | 1 042 to 1 |

| KwaZulu Natal | 3 195 to 1 | 665 to 1 |

| Limpopo | 4 478 to 1 | 612 to 1 |

| Mpumalanga | 5 124 to 1 | 825 to 1 |

| North West | 5 500 to 1 | 855 to 1 |

| Northern Cape | 2 738 to 1 | 869 to 1 |

| Western Cape | 3 967 to 1 | 180 to 1 |

| South Africa | 4 024 to 1 | 807 to 1 |

Hospitals

There are more than 400 public hospitals and more than 200 private hospitals. The provincial health departments manage the larger regional hospitals directly. Smaller hospitals and primary care clinics are managed at district level. The national Department of Health manages the 10 major teaching hospitals directly.[7]

The Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital is the third largest hospital in the world and it is located in Johannesburg.

| Province | Public clinic | Public hospital | Private clinic | Private hospital | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Cape | 731 | 91 | 44 | 17 | 883 |

| Free State | 212 | 34 | 22 | 13 | 281 |

| Gauteng | 333 | 39 | 286 | 83 | 741 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 592 | 77 | 95 | 12 | 776 |

| Limpopo | 456 | 42 | 14 | 10 | 522 |

| Mpumalanga | 242 | 33 | 23 | 13 | 311 |

| North West | 273 | 22 | 17 | 14 | 326 |

| Northern Cape | 131 | 16 | 10 | 2 | 159 |

| Western Cape | 212 | 53 | 170 | 39 | 474 |

| Total | 3 863 | 407 | 610 | 203 | 5083 |

| Province | Public hospital beds | Private hospitals beds | Total hospital beds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Cape | 13 200 | 1 723 | 14 923 |

| Free State | 4 798 | 2 337 | 7 135 |

| Gauteng | 16 656 | 14 278 | 30 934 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 22 048 | 4 514 | 26 562 |

| Limpopo | 7 745 | 600 | 8 345 |

| Mpumalanga | 4 745 | 1 252 | 5 997 |

| North West | 5 132 | 1 685 | 6 817 |

| Northern Cape | 1 523 | 293 | 1 816 |

| Western Cape | 12 241 | 4 385 | 16 626 |

| South Africa | 85 362 | 31 067 | 119 155 |

Uniform Patient Fee Schedule

The public sector uses a Uniform Patient Fee Schedule (UPFS) as a guide to billing for services. This is being used in all the provinces of South Africa, although in Western Cape, Kwa-Zulu Natal, and Eastern Cape, it is being implemented on a phased schedule. Implemented in November 2000, the UPFS categorises the different fees for every type of patient and situation.[8]

It groups patients into three categories defined in general terms, and includes a classification system for placing all patients into either one of these categories depending on the situation and any other relevant variables. The three categories include full paying patients—patients who are either being treated by a private practitioner, who are externally funded, or who are some types of non-South African citizens—, fully subsidised patients—patients who are referred to a hospital by Primary Healthcare Services—, and partially subsidised patients—patients whose costs are partially covered based on their income. There are also specified occasions in which services are free of cost.[8]

HIV/AIDS antiretroviral treatment

Because of its abundant cases of HIV/AIDS among citizens (about 5.6 million in 2009) South Africa has been working to create a program to distribute anti-retroviral therapy treatment, which has generally been limited in poorer countries, including neighboring country Lesotho. An anti-retroviral drug aims to control the amount of virus in the patient's body. In November 2003 the Operational Plan for Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Care, Management and Treatment for South Africa was approved, which was soon accompanied by a National Strategic Plan for 2007–2011. When South Africa freed itself of apartheid, the new health care policy has emphasised public health care, which is founded with primary health care. The National Strategic Plan therefore promotes distribution of anti-retroviral therapy through the public sector, and more specifically, primary health care.[9]

According to the World Health Organization, about 37% of infected individuals were receiving treatment at the end of 2009. It was not until 2009 that the South African National AIDS Council urged the government to raise the treatment threshold to be within the World Health Organization guidelines. Although this is the case, the latest anti-retroviral treatment guideline, released in February 2010, continue to fall short of these recommendations. In the beginning of 2010, the government promised to treat all HIV-positive children with anti-retroviral therapy, though throughout the year, there have been studies that show the lack of treatment for children among many hospitals. In 2009, a bit over 50% of children in need of anti-retroviral therapy were receiving it. Because the World Health Organization's 2010 guidelines suggest that HIV-positive patients need to start receiving treatment earlier than they have been, only 37% of those considered in need of anti-retroviral therapy are receiving it.

A controversy within the distribution of anti-retroviral treatment is the use of generic drugs. When an effective anti-retroviral drug became in available in 1996, only economically rich countries could afford it at a price of $10,000 to $15,000 per person per year. For economically disadvantaged countries, such as South Africa, to begin using and distributing the drug, the price had to be lowered substantially. In 2000, generic anti-retroviral treatments started being produced and sold at a much cheaper cost. Needing to compete with these prices, the big-brand pharmaceutical companies were forced to lower their prices. This competition has greatly benefited low economic countries and the prices have continued decline since the generic drug was introduced. The anti-retroviral treatment can now be purchased at as low as eighty-eight dollars per person per year. While the production of generic drugs has allowed the treatment of many more people in need, pharmaceutical companies feel that the combination of a decrease in price and a decrease in customers reduces the money they can spend on researching and developing new medications and treatments for HIV/AIDS.[10]

Pharmaceuticals

The technology of automated teller machines has been developed into pharmacy dispensing units, which have been installed in six sites (as of November 2018) and dispense chronic medication for illnesses such as HIV, hypertension, and diabetes for patients who do not need to see a clinician.[11]

Healthcare provision in the post-war period

Following the end of the Second World War, South Africa saw a rapid growth in the coverage of private medical provision, with this development mainly benefiting the predominantly middle class white population. From 1945 to 1960, the percentage of whites covered by health insurance grew from 48% to 80% of the population. Virtually the entire white population had shifted away from the free health services provided by the government by 1960, with 95% of non-whites remaining reliant upon the public sector for treatment.[12]

Membership of health insurance schemes became effectively compulsory for white South Africans due to membership of such schemes being a condition of employment, together with the fact that virtually all whites were formally employed. Pensioner members of many health insurance schemes received the same medical benefits as other members of these schemes, but free of costs.[13]

Since coming to power in 1994, the African National Congress (ANC) has implemented a number of measures to combat health inequalities in South Africa. These have included the introduction of free health care in 1994 for all children under the age of six together with pregnant and breastfeeding women making use of public sector health facilities (extended to all those using primary level public sector health care services in 1996) and the extension of free hospital care (in 2003) to children older than six with moderate and severe disabilities.[14]

National health insurance

The current government is working to establish a national health insurance (NHI) system out of concerns for discrepancies within the national health care system, such as unequal access to healthcare amongst different socio-economic groups. Although the details and outline of the proposal have yet to be released, it seeks to find ways to make health care more available to those who currently cannot afford it or whose situation prevents them from attaining the services they need. There is a discrepancy between money spent in the private sector which serves the wealthy (about US$1500 per head per year) and that spent in the public sector (about US$150 per head per year) which serves about 84% of the population. About 16% of the population have private health insurance. The total public funding for healthcare in 2019 was R222.6 billion (broken down to R98.2bn for District Health Services, R43.1bn for Central hospital services, R36.7bn for Provincial hospital services, R35.6bn for other health services and R8.8bn for facilities management & maintenance[15]). The NHI scheme is expected to require expenditure of about R336 billion.[5]

The NHI is speculated to propose that there be a single National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) for health insurance. This fund is expected to draw its revenue from general taxes and some sort of health insurance contribution. The proposed fund is supposed to work as a way to purchase and provide health care to all South African residents without detracting from other social services. Those receiving health care from both the public and private sectors will be mandated to contribute through taxes to the NHIF. The ANC hopes that the NHI plan will work to pay for health care costs for those who cannot pay for it themselves.

There are those who doubt the NHI and oppose its fundamental techniques. For example, many believe that the NHI will put a burden on the upper class to pay for all lower class health care. Currently, the vast majority of health care funds comes from individual contributions coming from upper class patients paying directly for health care in the private sector. The NHI proposes that health care fund revenues be shifted from these individual contributions to a general tax revenue.[2] Because the NHI aims to provide free health care to all South Africans, the new system is expected to bring an end to the financial burden facing public sector patients.[16]

Refugees and asylum seekers

The South African Constitution guarantees everyone "access to health care services" and states that "no one may be refused emergency medical treatment." Hence, all South African residents, including refugees and asylum seekers, are entitled to access to health care services.[17]

A Department of Health directive stated that all refugees and asylum seekers – without the need for a permit or a South African identity document – should have access to free anti-retroviral treatment at all public health care providers.[18]

The Refugee Act entitles migrants to full legal protection under the Bill of Rights as well as the same basic health care services which inhabitants of South Africa receive.[19]

Although infectious diseases "as prescribed from time to time" does bar entry, grant of temporary and permanent residence permits according to the Immigration Act, this does not include an infection with HIV and therefore migrants cannot be declined entry or medical treatment based on their HIV status.[20][21]

See also

- Timeline of healthcare in South Africa

- Africa Health Placements

- Emergency medical services in South Africa

- Health in South Africa

- Medical education in South Africa

- South African Department of Health

- South African Malaria Initiative

- South African Medical Research Council

- South African Military Health Service

- Disability in South Africa

Notes

- "WHO Statistical Information System". World Health Organization. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- Ataguba, John Ele-Ojo. "Health Care Financing in South Africa: moving toward universal coverage." Continuing Medical Education. February 2010 Vol. 28, Number 2.

- Bronkhorst, Quinton. "The most fattening fast-food meals in SA". businesstech.co.za. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Mogotlane, Mataniele Sophie (2003). Young, Anne; Van Niekerk, C. F.; Mogotlane, S (eds.). Juta's Manual of Nursing, Volume 1. South Africa: Juta and Company Ltd. pp. 6–9. ISBN 9780702156656.

- Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4.

- Makombo, Tawanda (June 2016). "Fast Facts: Public health sector in need of an antidote". Fast Facts. 6 (298): 6.

- Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4.

- User Guide-UPFS 2009. Department of Health of Republic of South Africa. June 2009

- Ruud KW, Srinivas SC, Toverud EL. Antiretroviral therapy in a South African public health care setting – facilitating and constraining factors. Southern Med Review (2009) 2; 2:29–34

- "HIV & AIDS in South Africa." AIDS & HIV Information from the AIDS Charity AVERT. AVERT: International HIV and AIDS Charity. Web. 10 December 2010.

- "These ATMs have swopped bills for pills. Here's why". Bhekisisa. 7 November 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "Microsoft Word - DoHConsDocFinal.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "Microsoft Word - DoHConsDocFinal.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "South African Child Gauge 2006 - FINAL.pdf" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- https://businesstech.co.za/news/budget-speech/300786/the-2019-budget-in-a-nutshell/

- "Yahoo". Yahoo. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- Constitution of South Africa of 1996. Article 27(1). http://www.elections.org.za/content/Documents/Laws-and-regulations/Constitution/Constitution-of-the-Republic-of-South-Africa,-1996/

- Directive: Refugees/Asylum Seekers with or without permit. Department of Health. Ref: BI 4/29 REFUG/ASYL 8 2007 http://www.probono.org.za/Downloads/asylum_seekers.pdf

- Refugees Act No. 130 of 1998 https://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/a130-98_0.pdf

- Wachira, George Mukundi. Migrants' right to health in Southern Africa (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- Immigration Act 13 of 2002 s. 29(1)(a) https://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/a13-02_0.pdf

References

- User Guide-UPFS 2009. Department of Health of Republic of South Africa. June 2009

- Ruud KW, Srinivas SC, Toverud EL. Antiretroviral therapy in a South African public health care setting – facilitating and constraining factors. Southern Med Review (2009) 2; 2:29–34

External links

- South Africa – Information by World Health Organization

- The State of the World's Midwifery – South Africa Country Profile