Health in Malawi

Malawi ranks 170th out of 174 in the World Health Organization lifespan tables; 88% of the population live on less than £2.40 per day; and 50% are below the poverty line.[1]

Introduction

Malawi is perturbed by a heavy double burden of disease from both communicable and non-communicable diseases. This is evidenced by high levels of child and adult mortality rates and high prevalence of diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, HIV/AIDS and other communicable diseases. In addition to that, there is growing evidence that suggests that there is a growing burden of non-communicable diseases which account nearly 32% of all deaths[2]. According to the recent 2018 Census done by the National Statistical Office in Malawi, the country has a total population of 17.5 million people. Nearly 15% of the population is composed of under five children, 36% is aged between 5 and 17 years and 49.7% is aged 18 years and above[3]

Health status

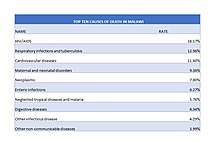

Top 10 causes of death in Malawi

There has been a shift in causes of mortality in many countries over the years. This can be as result of different factors like improved health interventions and access to health care, improved economic and social status and improved knowledge. This has resulted into a shift in the global burden of disease. According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evalution (IHME)(www.healthdata.org) the top ten causes of death in Malawi are[4]:

- HIV/AIDS (18.17%)

- Respiratory infections and tuberculosis (12.96%)

- Cardiovascular diseases (11.6%)

- Maternal and neonatal disorders (9.36%)

- Neoplasms (7.8%)

- Enteric infections (6.27%)

- Neglected tropical diseases and malaria (5.76%)

- Digestive diseases (4.34%)

- Other infectious diseases (4.29%)

- Other non-communicable disease (3.99%).[5]

Causes of death in Malawi

Causes of death in Malawi

Life expectancy

As of 2018 the estimated average life expectancy at birth in Malawi is at 64 years, with females having a slightly higher life expectancy at 67 years than males at 61.4 years.[6]

Fertility rate

In 2014 Malawi had a total fertility rate of 5.26 children born/woman.[7]

Infectious diseases

There is a high degree of risk for major infectious diseases, including bacterial and protozoal diarrhea, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, malaria, plague, schistosomiasis and rabies.[8]

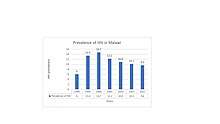

HIV/AIDS

In 2013 Malawi had a HIV/AIDS adult prevalence rate of 11%.[7] In 2013 there were 920,000 people living with HIV/AIDS, and 51,000 AIDS related deaths.[7] Data indicate that 8.8% of women and men aged 15-49 have HIV and the prevalence is higher among women than men (10.8% versus 6.4%).[9].

Due to the vast scope of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, many Malawian men believe that HIV contraction and death from AIDS are inevitable.[10] Older men in particular often claim that the HIV/AIDS epidemic is a punishment issued by God or other supernatural forces.[10] Other men refer to their own irresponsible sexual behaviors when explaining why they believe that death from AIDS is inevitable.[10]

These men sometimes claim that unprotected sex is natural (and therefore necessary and good) when justifying their lack of condom use during sex with extramarital partners.[10] Finally, some men identify as HIV-positive without having undergone testing for HIV, preferring to believe that they have already been infected so they can avoid adopting undesirable preventative measures such as condom use or strict fidelity.[10] Because of these fatalistic beliefs, many men continue engaging in extramarital sexual relations despite the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Malawi.[11]

However, despite these widespread feelings of fatalism, some men believe that they can avoid HIV contraction by modifying their personal behaviors.[10] Men who decide to change their behaviors to reduce their risk of infection are unlikely to use condoms consistently, particularly during marital intercourse; instead, they usually continue engaging in extramarital sexual relations, but alter the ways in which they choose their sexual partners.[10]

For example, before selecting extramarital sexual partners, men sometimes survey their peers to determine whether their potential partners are likely to have exposed themselves to the virus.[12] Men who choose their sexual partners based on external appearances and peer recommendations often believe that women who violate traditional gender norms by, for example, wearing modern clothing are more likely to carry HIV, while young girls, who are perceived as sexually inexperienced, are considered "pure".[10] Because of this perception, many people are concerned that schoolchildren in Malawi, particularly girls, are becoming exposed to the virus through sexual harassment or abuse by their instructors.[13]

Tuberculosis

_in_Malawi.jpg)

It is estimated that there are more than 14% cases of tuberculosis infections worldwide in year with 9 million new cases and nearly 1.7 deaths. In 2014 the incidence of tuberculosis was 227 per 100,000 people in Malawi. The good news is that the incidence is declining by 1.5% each, however the transmission still remains high[14].

Endemic diseases

Malaria

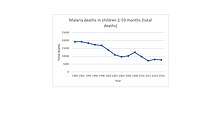

The disease continues to be a major public health problem in sub-Saharan Africa region in which Malawi is found. It is estimated that in 2017 the disease caused 403,000 deaths in this region, of which, 61% were children below the age of five.[15] Malaria was the leading cause of death in under five children in 2013 in Malawi accounting for 22% of all under five mortality[16]. Malaria affects numerous aspects of social and economic life in Malawi. High malaria prevalence affects fertility, savings and investment rates, crop choices, schooling and migration decisions.[17] There are a wide variety of cost-effective approaches to reduce the burden of malaria. Some current intervention tactics include case management, the use of insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying, and environmental vector control measures such as larvaciding (controlling mosquitoes at the larval stage through the use of chemicals) and filling and draining of breeding sites.[18] Each of these interventions has proven to have a high value of health gains achieved per dollar.[17] More specifically, mosquito nets are one of the most effective and widely used approaches. They are most effective in that they require a minimal amount of resource input and result in a large decrease in the prevalence of Malaria.[19]

In their article titled "The Economic and Social Burden of Malaria", Pia Malaney and Jeffrey Sachs present an argument for the prominent social theory regarding the intimate relationship between disease prevalence and poverty. They state that where malaria prospers most, human societies have prospered least.[17] In Poor Economics authors Banerjee and Duflo explain how poor healthcare contributes to the poverty trap.[20] That is, inadequacies of Malawi's healthcare lead to an increased prevalence of disease and other health issues, which, in turn, results in increased poverty incidence.[19]

A comparison of income in malarious and non-malarious countries indicates that average GDP (adjusted to give purchasing power parity (PPP)) in malarious countries in 1995 was US$1,526, compared with US$8,268 in countries without intensive malaria – more than a fivefold difference.[21] According to Jaimeson, effective intervention at the level of healthcare provision will have the greatest rate of return in the form of improved health.[22]

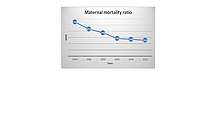

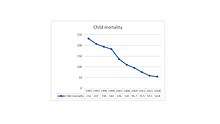

Maternal and child healthcare

Maternal health has improved in Malawi due to a number of factors. There has been improvement made in proportion of births attended by skilled professionel. The proportion has increased from 54.8% in 1992 to 87.4% in 2014. [23]. In addition to that, the maternal mortality is on the decrease though at a slower rate. Since 1990 the maternal mortality ratio has decreased from 1100 deaths per 100,000 people to 510 deaths per 100,000 people in 2013[24]. Improved access to sexual and reproductive health services has also contributed to the improvements in maternal health. Knowledge and of family planning is almost universal in Malawi with 98% of women and nearly 100% of men age 15-49 knowing at least one method of contraception.[25] Child health has also improved in Malawi. According to the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) report, the number of children dying before reaching their fifth birthday has declined, from 234 deaths per 1000 live births in 1992 to 63 deaths per 1000 live births in 2015-16.[26]. Child health is an important area to focus our efforts to better the health status because children are the most vulnerable group (especially those below the age of five), and most importantly it is their right to survive and live better lives.[27]. In Malawi, the child mortality rate is very high although there has been a decline over the years, from 234 deaths per 1000 live births in 1992 to 63 deaths per 1000 live births in 2015. In addition, the neonatal mortality has went down to 27 deaths per 1000 live birth in 2004.[28]

Non-communicable diseases

The shift in the burden of disease has led to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) becoming the leading cause of death globally, most of these deaths are due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, or diabetes. Mortality from many NCDs is on the rise worldwide, with a disproportionately larger burden in low-middle income countries (LMICs), where almost 3/4 of deaths globally occur from these causes. As of 2016 NCDs are estimated to account for 31.7% of deaths in Malawi, and the numbers are on the rise in countries throughout sub-Saharan Africa.[29]

Health indicators

The CIA World Fact Book's "country comparison to the world" ranking indicates how Malawi's health indicators compare to other countries in the world. Since the first case of HIV/AIDS in Malawi in 1985, HIV/AIDS has drastically affected Malawi's health indicators. Malawi's rankings:[7]

Conclusion

Malawi still faces a major burden of disease both from communicable and non-communicable diseases. There is indeed progress in trying to combat these problems but a lot need to be done.There will be always problems but the country needs to establish a good way of dealing with the problems that are there, with the available resources, to prevent more loss life from preventable and treatable diseases.

See also

References

- Scott, David (4 July 2017). "Developing pharmacy in Malawi". Pharmaceutical Journal. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- WHO. Health Situation Health Policies and Systems. 2017;1–2. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.cco

- Office NS. MALAWI POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS REPORT-2018 2018 Malawi Population and Housing Main Report. 2019;(May). Available from: http://www.nsomalawi.mw/images/stories/data_on_line/demography/census_2018/2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census Main Report.pdf

- https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

- https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

- https://www.who.int/countries/mwi/en/

- "The World Fact Book". Africa:: Malawi. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- "Malawi". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- Hardy EJ, Anderson BL. Communicable diseases. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33(1):30–4.

- Kaler, Amy (2004). "AIDS-talk in Everyday Life: The Presence of HIV/AIDS in Men's Informal Conversation in Southern Malawi". Social Science & Medicine. 59 (2): 285–97. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.023. PMID 15110420.

- Kalipeni, Ezekiel; Jayati Ghosh (2007). "Concern and practice among men about HIV/AIDS in low socioeconomic income areas of Lilongwe, Malawi". Social Science & Medicine. 64 (5): 1116–1127. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.013.

- Smith, Kirsten; Susan Watkins (2005). "Perceptions of Risk and Strategies for Prevention: Responses to HIV/AIDS in Rural Malawi". Social Science & Medicine. 60 (3): 649–660. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.009.

- Mitchell, Claudia (2004). "The Impact of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic on the Education Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Synthesis of the Findings and Recommendations of Three Country Studies (review)". Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa. 54 (1): 160–63. doi:10.1353/trn.2004.0024.

- Dunca S, Nimițan E, Ailiesei O, Ștefan M. Tehnica examinării caracterelor morfologice și tinctoriale ale bacteriilor. Microbiol Apl. 2007;70–6.

- King I, Iii M. Comment An Africa free of malaria. Lancet [Internet]. 2019;6736(19):10–1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31952-X

- Dunca S, Nimițan E, Ailiesei O, Ștefan M. Tehnica examinării caracterelor morfologice și tinctoriale ale bacteriilor. Microbiol Apl. 2007;70–6.

- Goodman, C.A.; P.G. Coleman; A.J. Mills (1999). "Cost-effectiveness of malaria control in sub-Saharan Africa". Lancet. 354 (9176): 378–385. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02141-8.

- Berthélemy, Jean-Claude; Josselin Tuillez; Ogobara Doumbo (13 June 2013). "Malaria and Protective Behaviours: Is There a Malaria Trap?". Malaria Journal. 12 (1): 200. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-12-200. PMC 3691867. PMID 23758967.

- Banjeree, Abhijit; Esther Duflo (2011). Poor economics: a radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty. New York: PublicAffairs.

- Gallup, J; J. Sachs (2001). "The Economic Burden of Malaria" (PDF). American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 64 (1–2 Suppl): 85–96. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.85. PMID 11425181.

- Jamison, Dean (2006). Disease control priorities in developing countries. New York: Oxford University Press World Bank.

- file:///C:/Users/Bruker1/Downloads/MALAWI%25202014%2520GOVERNMENT%2520MDGs%2520REPORT.pdf

- https://www.gapminder.org/tools/#$state$time$value=2013;&marker$select@$country=mwi&trailStartTime=1980;;&axis_x$which=time&domainMin:null&domainMax:null&zoomedMin:null&zoomedMax:null&scaleType=time&spaceRef:null;&axis_y$which=maternal_mortality_ratio_per_100000_live_births&domainMin:null&domainMax:null&zoomedMin:null&zoomedMax:null&scaleType=genericLog&spaceRef:null;;;&chart-type=bubbles

- National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi] and ICF. Malawi 2015-16 Demographic and Health Survey. DHS Progr [Internet]. 2015; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf

- National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi] and ICF. Malawi 2015-16 Demographic and Health Survey. DHS Progr [Internet]. 2015; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf

- https://www.unicef.org/health

- National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi] and ICF. Malawi 2015-16 Demographic and Health Survey. DHS Progr [Internet]. 2015; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf

- Gowshall M, Taylor-Robinson SD. The increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases in low-middle income countries: The view from Malawi. Int J Gen Med. 2018;11:255–64.