Health in Nigeria

Health, according to World Health Organization (WHO) in 1948, is described as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” By implication this involves a feeling of well-being that is enjoyed by individual when the body systems are functioning effectively and efficiently together and in harmony with the environment in order to achieve the objectives of good living.[1]

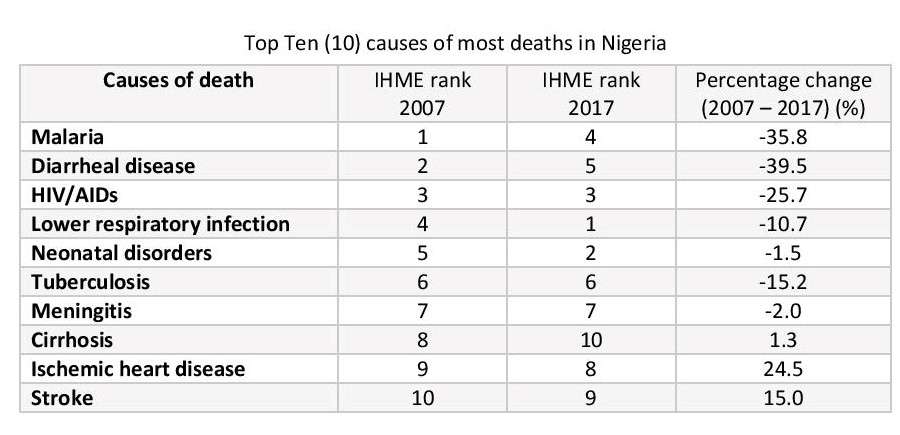

Good health and well-being is the focal point for a sustainable development and prosperous society. In Nigeria, there has been a major progress in the improvement of health since 1950. Although, lower respiratory infections, neonatal disorders and HIV/AIDS have ranked the topmost causes of deaths in Nigeria,[2] in the case of other diseases such as polio, malaria and tuberculosis, progress has been achieved. Among other threats to health are malnutrition, pollution and road traffic accidents.

Health can be measured by indicators such as life expectancy at birth, infant mortality rate, neonatal mortality rate, under-5 child mortality (U5MR) rate, and maternal mortality rate. However, features relating to personal and inborn of individuals such as age, sex, and genetic make-up are factors that help to determine health.[3] Other factors which affect health include socio-economic status, culture, education, indoor/outdoor environment, nutritional status, people’s own health practices and behaviours (for example the ability to identify when a family member is sick), as well as government approaches to policies and programs in its sectors, especially in the health sector.

Life expectancy and Under- 5 mortality rate

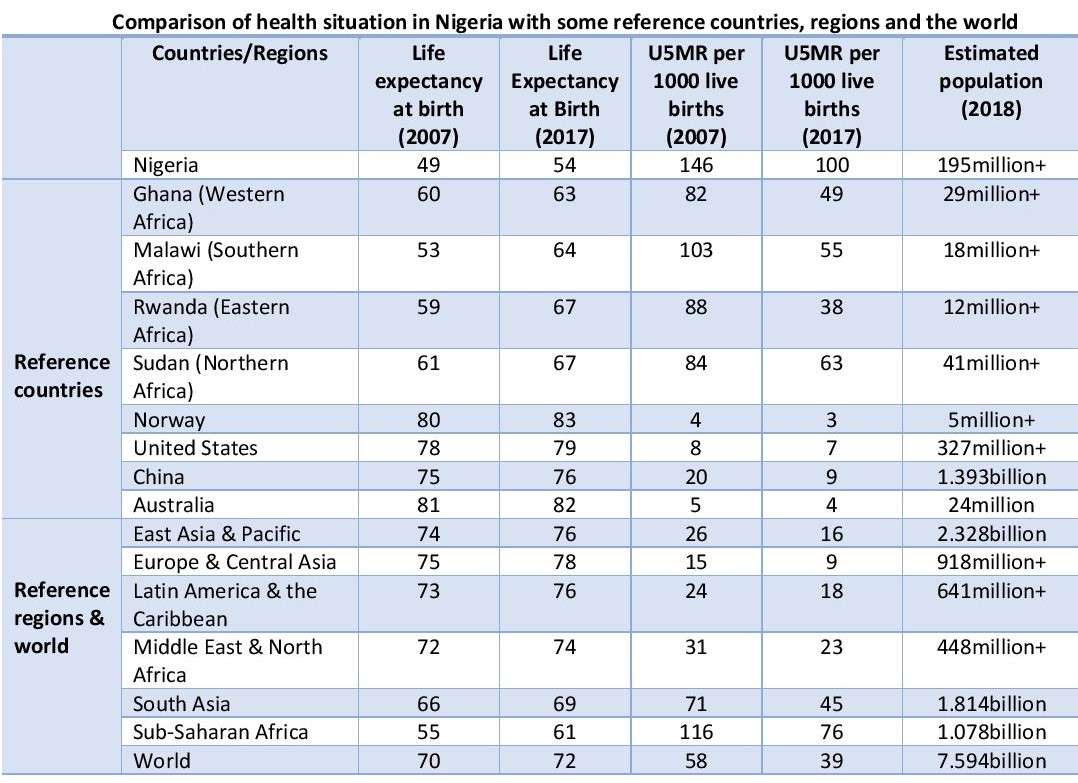

Life expectancy at birth in Nigeria is on the increase[4]. It increased from 49.4 in 2007 to approximately 54 in 2017[4]. In a decade (2007 – 2017), U5MR per 1000 live births drastically reduced from 145.7 to 100.2[5]. In comparison with some other reference countries (Ghana, Malawi, Rwanda, Sudan, Norway, United States of America, China and Australia), as shown in the second Table below, Nigeria with a population of about 195 million has performed poorly. Also, the country has not done better when compared with the world average and the World Bank regions namely: East Asia & Pacific, Europe & Central Asia, Latin America & the Caribbean, Middle East & North Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: Institute for Health Metric and Evaluation (IHME)[2]

_and_life_expectancy_at_birth_(1960_-_2017)_in_Nigeria.jpg)

Source: Under-5 Mortality Rate (per 1,000 live births) and Life expectancy at birth (years). Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation

(UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, UN DESA Population Division)[4][5]

Source: United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision. The World Bank Group[4][5][6]

Maternal mortality

In 2013, Maternal mortality in Nigeria is 560 deaths per 100,000 live births; whereas in 1980, it was 516 deaths 100,000 per live births.[7] This may be as a result of poor health facilities, lack of access to quality health care[8], malnutrition due to poverty, herder-farmer conflicts, female genital mutilations, abortions,[1] and displacements due to Boko Haram terrorism in the North East of Nigeria.[9] In Nigeria the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women is 1 in 23.[10] Nigeria’s abortion laws make it one of the most restrictive countries regarding abortion.[11]

A study published in 2019 investigated the competency of emergency obstetric care among health providers and found it lower than average.[12]

By 2030, if Nigeria is to reduce maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100, 000 live births (SDG goal 3 – target 1), all hands must be on deck to achieve it. People can start by promoting and protecting their own health and the health of those around them, by making well-informed choices, practicing safe sex and attending antenatal care in government approved health centres. There should be more awareness in communities about the importance of good health, healthy lifestyles as well as people’s right to quality health care services, especially for the most vulnerable such as women and children. Government, local leaders and other decision makers should be held accountable to their commitments to improve people’s access to health and health care.

Water supply and sanitation

Access to an improved water source stagnated at 47% of the population from 1990 to 2006, then increased to 54% in 2010. In urban areas access decreased from 80% to 65% in 2006, and then recovered to 74% in 2010.[13]

Adequate sanitation is typically in the form of septic tanks,liam as there is no central sewage system, except for Abuja and some areas of Lagos.[14] A 2006 study estimated that only 1% of Lagos households were connected to general sewers.[15] In 2016, mortality rate attributed to unsafe water, unsafe sanitation and lack of hygiene is 68.6 deaths per 100,000 populations.[16]

HIV/AIDS

Nigeria HIV/AIDS indicator and impact survey (NAIIS) 2018 revealed that the national HIV prevalence rate among adults ages 15–49 is 1.4 percent. The prevalence of HIV in Nigeria varies widely by region and states. Akwa Ibom State has the highest prevalence rate of HIV with 5.6 percent and disease burden of 200,051 percentage of deaths and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and followed by Benue State (4.9%, 188,482 DALYs) and Rivers (3.8%, 196,225 DALYs). The States, Jigawa (12,804 DALYs) and Katsina (26,597DALYs) both have the least prevalence rate of 0.3 percent.[17] The epidemic is more concentrated and driven by high-risk behaviors, including having multiple sexual partners, low risk perceptions, inadequate access to quality health care services,[18] as well as street/road hawking of goods by itinerant workers (hawkers) especially, around military and police checkpoints.[19] Other risk factors that contribute to the spread of HIV, including prostitution, high prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), clandestine high-risk homosexual/heterosexual practices, and women trafficking.[20] Youths and young adults in Nigeria are particularly vulnerable to HIV, with young women at higher risk than young men.[20]

Malaria

Malaria, a disease caused by mosquitoes has resulted in untold morbidity and mortality in Nigeria. Although, there has been slight decline in malarial transmission and deaths since 2007 it ranked the number one cause of deaths in the country[2], the disease still remain unflagging. As of 2012, the malaria prevalence rate was 11 percent.[21][22] A part of this data is from the President's Malaria Initiative which identifies Nigeria as a high-burden country.[23] Nigeria's branch dealing with this problem, the National Malaria Control Program recognized the problem and embraced the World Malaria Day theme of "End Malaria for Good".[24]

In 2017, according to IHME ranking, malaria ranked the fourth on the causes of most deaths in Nigeria with U5MR and under-1 child mortality of 103.2 deaths and 62.6 deaths per 1,000 live births respectively[2]. With pockets of high-level transmission persisting in states across Nigeria coupled with the never-ending struggle against drug and insecticide resistance as well as the socio-economic costs associated with a failure to eradicate the disease[25], malaria eradication by 2050 seems unachievable. However, the step to eradicate the disease is a bold attainable goal if concerted efforts are put in place. The challenge of ineffective management of malaria prevention and control programs and inadequate use of data to inform strategies should be addressed. The control of mosquitoes, high quality diagnosis, and treatment are very necessary if the problem is to be successfully eradicated. Strong and committed leadership at various levels of government in Nigeria, reinforced through transparency and independent accountability mechanisms are very important to ensure a complete eradication of malaria in the country.[25]

Endemic diseases

In 1985, an incidence of yellow fever devastated a town in Nigeria, leading to the death of 1000 people. In a span of 5 years, the epidemic grew, with a resulting rise in mortality. The vaccine for yellow fever has been in existence since the 1930s.[26] There are other endemic diseases in the country which include malaria, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, typhoid, and meningitis.[27] Travelers are normally advised to get travel vaccines and medicines because of the risk of these diseases in the country.[27]

Food

Nutrition, especially in the North of the country, is often poor. Since 2002 food staples are supposed to be fortified with nutrients such as vitamin A, folic acid, zinc, iodine and iron. Bill Gates, said there had been “pushback” by some in Nigerian industry as this reduced profit margins. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is donating $5m over four years to implement a rigorous testing regime to make sure these standards are met. These nutrients would reach poorer children who ate mainly a cereal and beans diet at very low cost and reduce the risk of stunting. Vitamin A would reduce the risk of death from measles or diarrhoea. In some districts 7% of children die before they reach the age of five. Nearly half of these are attributable to malnutrition. Aliko Dangote, whose companies supply salt, sugar and flour, said there would need to be a crack down on the import of low-quality foodstuff, often smuggled into local markets.[28]

Pollution

Traffic congestion in Lagos, environmental pollution:water pollution, and air pollution; and noise pollution are major health issues.

The aquatic systems in Nigeria, no doubt, are reservoirs for toxic chemicals and dead-ends for different kinds of chemical compounds and their products. The activities of oil and gas industries as well as widespread discharge of effluents into water ways is an eyesore. Chemical substances such as polyaromatic hydrocarbons, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances as well as heavy metals from point (see point pollution)and non-point (see nonpoint pollution) sources finds their way into oceans, rivers and streams and contaminates it.[29][30][31] In 2018, The Nation newspaper reported improper waste disposal in the country, emphasizing that there is no proper waste management system, hence the cause of the indiscriminate dumping of refuse, used polythene bags, plastic bottles and other liquid and solid wastes in the environment.[32] The Huffingtonpost in May 2017[33] raised an alarm on the incessant dumping of plastics in the ocean. It posited that 'the oceans are drowning in plastics – and no one is paying attention to the menace'; and by indication, it seems people are overwhelmed by their own waste. Amidst this, Ellen MacArthur Foundation in Partnership with the World Economic Forum predicted that by 2050, plastic in the oceans will outweigh fish. With expected surge in consumption, negative externalities related to plastics will multiply by that time.Most wastes materials contain estrogenic chemicals - (estrogens) and androgenic chemicals - (androgens) and they have potential to leach into the surrounding environment, impact on the ecosystem and may alter hormonal functions.[31][34] These contaminants and many other chemicals are toxic to aquatic lives, most often affecting their life spans and ability to reproduce[34]; they make their way up the food chain as predator eats prey and bioaccumulate in the adipose tissues of these organisms.

Road traffic accidents

Every year the lives of approximately 1.25 million people are cut short as a result of a road traffic crash. Between 20 and 50 million more people suffer non-fatal injuries, with many incurring a disability as a result of their injury. Road traffic injuries cause considerable economic losses to individuals, their families, and to nations as a whole. These losses arise from the cost of treatment as well as lost productivity for those killed or disabled by their injuries, and for family members who need to take time off work or school to care for the injured. Road traffic crashes cost most countries 3% of their gross domestic product. Road traffic injuries are the leading cause of death among people aged between 15 and 29 years.[35]

Over 3 400 people die on the world's roads every day and tens of millions of people are injured or disabled every year. Children, pedestrians, cyclists and older people are among the most vulnerable of road users. WHO works with partners - governmental and nongovernmental - around the world to raise the profile of the preventability of road traffic injuries and promote good practice related to addressing key behaviour risk factors – speed, drink-driving, the use of motorcycle helmets, seat-belts and child restraints.[36]

With the continued dangerous trend of road traffic collision in Nigeria, which in 2013 placed it as one of the most road traffic accident (RTA) prone countries worldwide (the most in Africa),[37][38] the Nigerian government saw the need to establish the present Federal Road Safety Corps in 1988 to address the carnage on the highways.

Level and trend of road traffic accidents

The Federal Road Safety Corps (FRSC) says 456 people died and 3404 others were injured in 826 accidents recorded nationwide in January (2018).

The FRSC stated this in its CCC report for January signed by its Corps Marshal, Boboye Oyeyemi.[39]

Causes of road traffic accidents

The causes of road traffic accidents depend on a list of factors which can be broadly divided into:

- (i). Vehicle operator or driver factors

- (ii). Vehicle factors

- (iii). Road pavement condition factors

- (iv). Environmental factors.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals

In September 2015, the General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Building on the principle of “leaving no one behind”, the new Agenda emphasizes a holistic approach to achieving sustainable development for all.[40] The Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

- The Target 3.6 under goal 3 is designed specifically to addresses the issue of road traffic accident: By 2020, halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents §

The Federal Government of Nigeria has put some mechanisms in place to ensure implementation of the SDGs in the country[41] however, Nigeria is still far from achieving this goal.

Traditional/Alternative medicine

As recent reports have shown, in addition to the many benefits there are also risks associated with the different types of Traditional Medicine / Complimentary or alternative Medicine. Although consumers today have widespread access to various TM/CAM treatments and therapies, they often do not have enough information on what to check when using TM/CAM in order to avoid unnecessary harm.[42] While traditional medicine has a lot to contribute to the health and economy, much harm has resulted from unregulated sale and misuse of traditional/alternative medicine and herbs in the country and has significantly delayed patients' seeking professional healthcare.[43]

See also

- Healthcare in Nigeria

- Federal Ministry of Health

- Smoking in Nigeria

- Federal Road Safety Corps

References

- "Health Challenges in the Present Democratic Era in Nigeria: The Place of Technology". Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "What causes the most premature death in Nigeria?". Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- Skolnik, Richard (2016). Global health trend 101, 3rd ed. USA: Michael Brown. ISBN 978-1-284-05054-7.

- "Life expectancy at birth, total (years) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

- "Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- "Population, total | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- "Maternal mortality". Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- Welcome, MenizibeyaOsain (2011). "The Nigerian health care system: Need for integrating adequate medical intelligence and surveillance systems". Journal of Pharmacy and Bioallied Sciences. 3 (4): 470–8. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.90100. ISSN 0975-7406. PMC 3249694. PMID 22219580.

- "Boko Haram: A decade of terror explained". July 30, 2019.

- "The state of the world's midwifery 2014". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- Iyioha, Irehobhude O. (2 November 2015). Comparative health law and policy : critical perspectives on Nigerian and global health law. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-4724-3675-7.

- Okonofua, F.; Ntoimo, L.F.C.; Ogu, R.; Galadanci, R.; Gana, M.; et al. (April 2019). "Assessing the knowledge and skills on emergency obstetric care among health providers: Implications for health systems strengthening in Nigeria". PLOS ONE. 14 (4): e0213719. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1413719O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213719. PMC 6453439. PMID 30958834.

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, 2010 estimates for water and sanitation

- USAID: Nigeria Water and Sanitation Profile, ca. 2007

- Matthew Gandy:Water, Sanitation, and the Modern City: Colonial and post-colonial experiences in Lagos and Mumbai, Human Development Report Office Occasional Paper, 2006

- "Mortality rate attributed to unsafe water, unsafe sanitation and lack of hygiene (per 100,000 population)". Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- "Nigeria prevalence rate". Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- National Agency for the Conrol of AIDS. Abuja, Nigeria. "Global AIDS Response Country Progress Report 2015". NACA.

- Nnadozie, Prince; Onyenanu, Sylva (October 24, 2018). "Sero-Prevalence of HIV in Hawkers: A Rural Community-Based Cohorts in Ilesa, Nigeria". In: Proceedings of Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science & Technology, Trondheim, "Global Health Day": 16.

- "2008 Country Profile: Nigeria". U.S. Department of State. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 August 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- "Nigeria-Malaria" Accessed May 1, 2016

- "President's Malaria Initiative-Nigeria" Accessed May 1, 2016

- "Where We Work" Accessed May 12, 2016

- "National Malaria Control Program-Home" Accessed May 12, 2016

- Feachem, Richard G A; Chen, Ingrid; Akbari, Omar; Bertozzi-Villa, Amelia; Bhatt, Samir; Binka, Fred; Boni, Maciej F; Buckee, Caroline; Dieleman, Joseph (2019). "Malaria eradication within a generation: ambitious, achievable, and necessary". The Lancet. 394 (10203): 1056–1112. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31139-0. PMID 31511196.

- "Nigerian National Merit Award". www.meritaward.ng.

- "Health Information for Travelers to Nigeria - Traveler view | Travelers' Health | CDC". wwwnc.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2019-09-21.

- "Nigerian food sector commits to nutrient fortification". Financial Times. 5 August 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Adeogun, Aina O.; Ibor, Oju R.; Adeduntan, Sherifat D.; Arukwe, Augustine (May 2016). "Corrigendum to "Intersex and alterations in reproductive development of a cichlid, Tilapia guineensis, from a municipal domestic water supply lake (Eleyele) in Southwestern Nigeria" [Sci. Total Environ. 541 (2016) 372–382]". Science of the Total Environment. 551-552: 752. Bibcode:2016ScTEn.551..752A. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.02.069. ISSN 0048-9697.

- Ibor, Oju R.; Adeogun, Aina O.; Fagbohun, Olusegun A.; Arukwe, Augustine (December 2016). "Gonado-histopathological changes, intersex and endocrine disruptor responses in relation to contaminant burden in Tilapia species from Ogun River, Nigeria". Chemosphere. 164: 248–262. Bibcode:2016Chmsp.164..248I. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.087. ISSN 0045-6535.

- Khan, Essa A.; Bertotto, Luisa B.; Dale, Karina; Lille-Langøy, Roger; Yadetie, Fekadu; Karlsen, Odd André; Goksøyr, Anders; Schlenk, Daniel; Arukwe, Augustine (2019-05-15). "Modulation of Neuro-Dopamine Homeostasis in Juvenile Female Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) Exposed to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Perfluoroalkyl Substances". Environmental Science & Technology. 53 (12): 7036–7044. Bibcode:2019EnST...53.7036K. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b00637. ISSN 0013-936X.

- "Improper waste disposal: A threat to our survival". The Nation Newspaper. 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- Mosbergen, Dominique (2017-04-27). "The Oceans Are Drowning In Plastic -- And No One's Paying Attention". HuffPost. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- Arukwe, Augustine (2008-04-09). "Steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein and cholesterol side-chain cleavage (P450scc)-regulated steroidogenesis as an organ-specific molecular and cellular target for endocrine disrupting chemicals in fish". Cell Biology and Toxicology. 24 (6): 527–540. doi:10.1007/s10565-008-9069-7. ISSN 0742-2091.

- "Road Safety". WHO | Regional Office for Africa.

- WHO

- List of countries by traffic-related death rate. Wikipedia. 2018-04-11.

- . World Health Organization. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Nigeria records 456 road accident deaths in one month - Premium Times Nigeria". April 12, 2018.

- "#Envision2030: 17 goals to transform the world for persons with disabilities | United Nations Enable". www.un.org.

- "Assessing SDGs implementation in Nigeria".

- "22750_volume.indd" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- "Excessive intake of local herbs causes kidney damage-Expert". Daily Trust. March 19, 2018.

External links

- "'A breakdown of our primary health care system'," Seattle Post-Intelligencer

- 'Asangansi Complex Dynamics in the Socio-Technical Infrastructure: the case of the Nigerian Health Management Information System'

- Health in Nigeria

- Health insurance

- The State of the World's Midwifery - Nigeria Country Profile