Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a collection of 17 global goals designed to be a "blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all".[2] The SDGs, set in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly and intended to be achieved by the year 2030, are part of UN Resolution 70/1, the 2030 Agenda.[3][4]

The Sustainable Development Goals are:

- No Poverty

- Zero Hunger

- Good Health and Well-being

- Quality Education

- Gender Equality

- Clean Water and Sanitation

- Affordable and Clean Energy

- Decent Work and Economic Growth

- Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

- Reducing Inequality

- Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Responsible Consumption and Production

- Climate Action

- Life Below Water

- Life On Land

- Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

- Partnerships for the Goals

The goals are broad based and interdependent. The 17 sustainable development goals each have a list of targets which are measured with indicators. In an effort to make the SDGs successful, data on the 17 goals has been made available in an easily-understood form.[5] A variety of tools exist to track and visualize progress towards the goals.

History

Background

.jpg)

In 1972, governments met in Stockholm, Sweden for the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, to consider the rights of the family to a healthy and productive environment.[6] In 1983, the United Nations created the World Commission on Environment and Development (later known as the Brundtland Commission), which defined sustainable development as "meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".[7] In 1992, the first United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) or Earth Summit was held in Rio de Janeiro, where the first agenda for Environment and Development, also known as Agenda 21, was developed and adopted.

In 2012, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD), also known as Rio+20, was held as a 20-year follow up to UNCED. Colombia proposed the idea of the SDGs at a preparation event for Rio+20 held in Indonesia in July 2011.[8] In September 2011, this idea was picked up by the United Nations Department of Public Information 64th NGO Conference in Bonn, Germany. The outcome document proposed 17 sustainable development goals and associated targets. In the run-up to Rio+20 there was much discussion about the idea of the SDGs. At the Rio+20 Conference, a resolution known as "The Future We Want" was reached by member states.[9] Among the key themes agreed on were poverty eradication, energy, water and sanitation, health, and human settlement.

The Rio+20 outcome document mentioned that "at the outset, the OWG [Open Working Group] will decide on its methods of work, including developing modalities to ensure the full involvement of relevant stakeholders and expertise from civil society, Indigenous Peoples, the scientific community and the United Nations system in its work, in order to provide a diversity of perspectives and experience".[9]

In January 2013, the 30-member UN General Assembly Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals was established to identify specific goals for the SDGs. The Open Working Group (OWG) was tasked with preparing a proposal on the SDGs for consideration during the 68th session of the General Assembly, September 2013 – September 2014.[10] On 19 July 2014, the OWG forwarded a proposal for the SDGs to the Assembly. After 13 sessions, the OWG submitted their proposal of 8 SDGs and 169 targets to the 68th session of the General Assembly in September 2014.[11] On 5 December 2014, the UN General Assembly accepted the Secretary General's Synthesis Report, which stated that the agenda for the post-2015 SDG process would be based on the OWG proposals.[12]

Ban Ki-moon, the United Nations Secretary-General from 2007 to 2016, has stated in a November 2016 press conference that: "We don’t have plan B because there is no planet B."[13] This thought has guided the development of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Post-2015 Development Agenda was a process from 2012 to 2015 led by the United Nations to define the future global development framework that would succeed the Millennium Development Goals. The SDGs were developed to succeed the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) which ended in 2015. The gaps and shortcomings of MDG Goal 8 (To develop a global partnership for development) led to identifying a problematic "donor-recipient" relationship.[14] Instead, the new SDGs favor collective action by all countries.[14]

The UN-led process involved its 193 Member States and global civil society. The resolution is a broad intergovernmental agreement that acts as the Post-2015 Development Agenda. The SDGs build on the principles agreed upon in Resolution A/RES/66/288, entitled "The Future We Want".[15] This was a non-binding document released as a result of Rio+20 Conference held in 2012.[15]

Ratification

Negotiations on the Post-2015 Development Agenda began in January 2015 and ended in August 2015. The negotiations ran in parallel to United Nations negotiations on financing for development, which determined the financial means of implementing the Post-2015 Development Agenda; those negotiations resulted in adoption of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda in July 2015. A final document was adopted at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in September 2015 in New York.[16]

On 25 September 2015, the 193 countries of the UN General Assembly adopted the 2030 Development Agenda titled "Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development".[4][17] This agenda has 92 paragraphs. Paragraph 51 outlines the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and the associated 169 targets and 232 indicators.

Description

There are 169 targets for the 17 goals. Each target has between 1 and 3 indicators used to measure progress toward reaching the targets. In total, there are 232 approved indicators that will measure compliance.[18][19] The United Nations Development Programme has been asked to provide easy to understand lists of targets, facts and figures for each of the 17 SDGs.[20] The 17 goals listed below as sub-headings use the 2-to-4 word phrases that identify each goal. Directly below each goal, in quotation marks, is the exact wording of the goal in one sentence. The paragraphs that follow present some information about a few targets and indicators related to each goal.

Goal 1: No poverty

"End poverty in all its forms everywhere."[21]

Extreme poverty has been cut by more than half since 1990. Still, around 1 in 10 people live on less than the target figure of international-$1.25 per day.[22] A very low poverty threshold is justified by highlighting the need of those people who are worst off.[23] SDG 1 is to end extreme poverty globally by 2030.

That target may not be adequate for human subsistence and basic needs, however.[24] It is for this reason that changes relative to higher poverty lines are also commonly tracked.[25] Poverty is more than the lack of income or resources: People live in poverty if they lack basic services such as healthcare, security, and education. They also experience hunger, social discrimination, and exclusion from decision-making processes. One possible alternative metric is the Multidimensional Poverty Index.[26]

Children make up the majority – more than half – of those living in extreme poverty. In 2013, an estimated 385 million children lived on less than US$1.90 per day.[27] Still, these figures are unreliable due to huge gaps in data on the status of children worldwide. On average, 97 percent of countries have insufficient data to determine the state of impoverished children and make projections towards SDG Goal 1, and 63 percent of countries have no data on child poverty at all.[27]

Women face potentially life-threatening risks from early pregnancy and frequent pregnancies. This can result in lost hope for an education and for a better income. Poverty affects age groups differently, with the most devastating effects experienced by children. It affects their education, health, nutrition, and security, impacting emotional and spiritual development.

Achieving Goal 1 is hampered by lack of economic growth in the poorest countries of the world, growing inequality, increasingly fragile statehood, and the impacts of climate change.

Goal 2: Zero hunger

"End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture."[28]

Goal 2 states that by 2030 we should end hunger and all forms of malnutrition. This would be accomplished by doubling agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers (especially women and indigenous peoples), by ensuring sustainable food production systems, and by progressively improving land and soil quality. Agriculture is the single largest employer in the world, providing livelihoods for 40% of the global population. It is the largest source of income for poor rural households. Women make up about 43% of the agricultural labor force in developing countries, and over 50% in parts of Asia and Africa. However, women own only 20% of the land.

Other targets deal with maintaining genetic diversity of seeds, increasing access to land, preventing trade restriction and distortions in world agricultural markets to limit extreme food price volatility, eliminating waste with help from the International Food Waste Coalition, and ending malnutrition and undernutrition of children.

Globally, 1 in 9 people are undernourished, the vast majority of whom live in developing countries. Undernutrition causes wasting or severe wasting of 52 million children worldwide,[29] and contributes to nearly half (45%) of deaths in children under five – 3.1 million children per year.[30] Chronic malnutrition, which affects an estimated 155 million children worldwide, also stunts children's brain and physical development and puts them at further risk of death, disease, and lack of success as adults.[29] As of 2017, only 26 of 202 UN member countries are on track to meet the SDG target to eliminate undernourishment and malnourishment, while 20 percent have made no progress at all and nearly 70 percent have no or insufficient data to determine their progress.[29]

A report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) of 2013 stated that the emphasis of the SDGs should not be on ending poverty by 2030, but on eliminating hunger and under-nutrition by 2025.[31] The assertion is based on an analysis of experiences in China, Vietnam, Brazil, and Thailand. Three pathways to achieve this were identified: 1) agriculture-led; 2) social protection- and nutrition- intervention-led; or 3) a combination of both of these approaches.[31]

A study published in Nature concluded that it is unlikely there will be an end to malnutrition by 2030.[32]

Goal 3: Good health and well-being for people

"Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages."[33]

Significant strides have been made in increasing life expectancy and reducing some of the common killers associated with child and maternal mortality. Between 2000 and 2016, the worldwide under-five mortality rate decreased by 47 percent (from 78 deaths per 1,000 live births to 41 deaths per 1,000 live births).[29] Still, the number of children dying under age five is extremely high: 5.6 million in 2016 alone.[29] Newborns account for a growing number of these deaths, and poorer children are at the greatest risk of under-5 mortality due to a number of factors.[29] SDG Goal 3 aims to reduce under-five mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births. But if current trends continue, more than 60 countries will miss the SDG neonatal mortality target for 2030. About half of these countries would not reach the target even by 2050.[29]

Goal 3 also aims to reduce maternal mortality to less than 70 deaths per 100,000 live births.[34] Though the maternal mortality ratio declined by 37 percent between 2000 and 2015, there were approximately 303,000 maternal deaths worldwide in 2015, most from preventable causes.[29] In 2015, maternal health conditions were also the leading cause of death among girls aged 15–19.[29] Data for girls of greatest concern – those aged between 10-14 - is currently unavailable. Key strategies for meeting SDG Goal 3 will be to reduce adolescent pregnancy (which is strongly linked to gender equality), provide better data for all women and girls, and achieve universal coverage of skilled birth attendants.[29]

Similarly, progress has been made on increasing access to clean water and sanitation and on reducing malaria, tuberculosis, polio, and the spread of HIV/AIDS. From 2000-2016, new HIV infections declined by 66 percent for children under 15 and by 45 percent among adolescents aged 15–19.[29] However, current trends mean that 1 out of 4 countries still won't meet the SDG target to end AIDS among children under 5, and 3 out of 4 will not meet the target to end AIDS among adolescents.[29] Additionally, only half of women in developing countries have received the health care they need, and the need for family planning is increasing exponentially as the population grows. While needs are being addressed gradually, more than 225 million women have an unmet need for contraception.

Goal 3 aims to achieve universal health coverage, including access to essential medicines and vaccines.[34] It proposes to end the preventable death of newborns and children under 5 and to end epidemics such as AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and water-borne diseases, for example.[34] 2016 rates for the third dose of the pertussis vaccine (DTP3) and the first dose of the measles vaccine (MCV1) reached 86 percent and 85 percent, respectively. Yet about 20 million children did not receive DTP3 and about 21 million did not receive MCV1.[29] Around 2 in 5 countries will need to accelerate progress in order to reach SDG targets for immunization.[29]

Attention to health and well-being also includes targets related to the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, deaths and injuries from traffic accidents and from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination.[34]

Goal 4: Quality education

"Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all."[35]

Major progress has been made in access to education, specifically at the primary school level, for both boys and girls. The number of out-of-school children has almost halved from 112 million in 1997 to 60 million in 2014.[36] Still, at least 22 million children in 43 countries will miss out on pre-primary education unless the rate of progress doubles.[29]

Access does not always mean quality of education or completion of primary school. 103 million youth worldwide still lack basic literacy skills, and more than 60 percent of those are women. In one out of four countries, more than half of children failed to meet minimum math proficiency standards at the end of primary school, and at the lower secondary level, the rate was 1 in 3 countries.[29] Target 1 of Goal 4 is to ensure that, by 2030, all girls and boys complete free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education.

Additionally, progress is difficult to track: 75 percent of countries have no or insufficient data to track progress towards SDG Goal 4 targets for learning outcomes (target 1), early childhood education (target 2), and effective learning environments.[29] Data on learning outcomes and pre-primary school are particularly scarce; 70 percent and 40 percent of countries lack adequate data for these targets, respectively.[29] This makes it hard to analyze and identify the children at greatest risk of being left behind.

Goal 5: Gender equality

"Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls."[37]

According to the UN, "gender equality is not only a fundamental human right, but a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world."[38] Providing women and girls with equal access to education, health care, decent work, and representation in political and economic decision-making processes will nurture sustainable economies and benefit societies and humanity at large. A record 143 countries guaranteed equality between men and women in their constitutions as of 2014. However, another 52 had not taken this step. In many nations, gender discrimination is still woven into the fabric of legal systems and social norms. Even though SDG5 is a stand-alone goal, other SDGs can only be achieved if the needs of women receive the same attention as the needs of men. Issues unique to women and girls include traditional practices against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, such as female genital mutilation.

Child marriage has declined over the past decades, yet there is no region that is currently on track to eliminate the practice and reach SDG targets by 2030.[29] If current trends continue, between 2017 and 2030, 150 million girls will be married before they turn 18.[29] Though child marriages are four times higher among the poorest than the wealthiest in the world, most countries need to accelerate progress among both groups in order to reach the SDG Goal 5 target to eliminate child marriage by 2030.[29]

Achieving gender equality will require enforceable legislation that promotes empowerment of all women and girls and requires secondary education for all girls.[39] The targets call for an end to gender discrimination and for empowering women and girls through technology[40] Some have advocated for "listening to girls". The assertion is that the SDGs can deliver transformative change for girls only if girls are consulted. Their priorities and needs must be taken into account. Girls should be viewed not as beneficiaries of change, but as agents of change. Engaging women and girls in the implementation of the SDGs is crucial.[41]

The World Pensions Council (WPC) has insisted on the transformational role gender-diverse that boards can play in that regard, predicting that 2018 could be a pivotal year, as "more than ever before, many UK and European Union pension trustees speak enthusiastically about flexing their fiduciary muscles for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, including SDG5, and to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls."[42]

Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation

_(38403428742).jpg)

.jpg)

"Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all."[43]

The Sustainable Development Goal Number 6 (SDG6) has eight targets and 11 indicators that will be used to monitor progress toward the targets. Most are to be achieved by the year 2030. One is targeted for 2020.[44]

The first three targets relate to drinking water supply and sanitation.[44] Worldwide, 6 out of 10 people lack safely managed sanitation services, and 3 out of 10 lack safely managed water services.[29] Safe drinking water and hygienic toilets protect people from disease and enable societies to be more productive economically. Attending school and work without disruption is critical to successful education and successful employment. Therefore, toilets in schools and work places are specifically mentioned as a target to measure. "Equitable sanitation" calls for addressing the specific needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations, such as the elderly or people with disabilities. Water sources are better preserved if open defecation is ended and sustainable sanitation systems are implemented.

Ending open defecation will require provision of toilets and sanitation for 2.6 billion people as well as behavior change of the users.[45] This will require cooperation between governments, civil society, and the private sector.[46]

The main indicator for the sanitation target is the "Proportion of population using safely managed sanitation services, including a hand-washing facility with soap and water".[47] However, as of 2017, two-thirds of countries lacked baseline estimates for SDG indicators on hand washing, safely managed drinking water, and sanitation services.[29] From those that were available, the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) found that 4.5 billion people currently do not have safely managed sanitation.[45] To meet SDG targets for sanitation by 2030, nearly one-third of countries will need to accelerate progress to end open defecation, including Brazil, China, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Pakistan.[29]

The Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) has made it its mission to achieve SDG6.[48][49] SuSanA's position is that the SDGs are highly interdependent. Therefore, the provision of clean water and sanitation for all is a precursor to achieving many of the other SDGs.[50]

Goal 7: Affordable and clean energy

"Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all."[51]

Targets for 2030 include access to affordable and reliable energy while increasing the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. This would involve improving energy efficiency and enhancing international cooperation to facilitate more open access to clean energy technology and more investment in clean energy infrastructure. Plans call for particular attention to infrastructure support for the least developed countries, small islands and land-locked developing countries.[51]

As of 2017, only 57 percent of the global population relies primarily on clean fuels and technology for cooking, falling short of the 95 percent target.[29]

Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth

"Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all."[52]

World Pensions Council (WPC) development economists have argued that the twin considerations of long-term economic growth and infrastructure investment were not prioritized enough. The fact they were designated as the number 8 and number 9 objective respectively was considered a rather "mediocre ranking [which] defies common sense".[53]

For the least developed countries, the economic target is to attain at least a 7 percent annual growth in gross domestic product (GDP). Achieving higher productivity will require diversification and upgraded technology along with innovation, entrepreneurship, and the growth of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Some targets are for 2030; others are for 2020. The target for 2020 is to reduce youth unemployment and operationalize a global strategy for youth employment. Implementing the Global Jobs Pact of the International Labour Organization is also mentioned.

By 2030, the target is to establish policies for sustainable tourism that will create jobs. Strengthening domestic financial institutions and increasing Aid for Trade support for developing countries is considered essential to economic development. The Enhanced Integrated Framework for Trade-Related Technical Assistance to Least Developed Countries is mentioned as a method for achieving sustainable economic development.[52]

Goal 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

"Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation."[54]

Manufacturing is a major source of employment. In 2016, the least developed countries had less "manufacturing value added per capita". The figure for Europe and North America amounted to US$4,621, compared to about $100 in the least developed countries.[55] The manufacturing of high products contributes 80 percent to total manufacturing output in industrialized economies but barely 10 percent in the least developed countries.

Mobile-cellular signal coverage has improved a great deal. In previously "unconnected" areas of the globe, 85 percent of people now live in covered areas. Planet-wide, 95 percent of the population is covered.[55]

Goal 10: Reducing inequalities

"Reduce income inequality within and among countries."[56]

Target 10.1 is to "sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average". This goal, known as 'shared prosperity', is complementing SDG 1, the eradication of extreme poverty, and it is relevant for all countries in the world.[57]

Target 10.3 is to reduce the transaction costs for migrant remittances to below 3 percent. The target of 3 percent was established as the cost that international migrant workers would pay to send money home (known as remittances). However, post offices and money transfer companies currently charge 6 percent of the amount remitted. Worse, commercial banks charge 11 percent. Prepaid cards and mobile money companies charge 2 to 4 percent, but those services were not widely available as of 2017 in typical "remittance corridors."[58]

Goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities

"Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable."[59]

The target for 2030 is to ensure access to safe and affordable housing. The indicator named to measure progress toward this target is the proportion of urban population living in slums or informal settlements. Between 2000 and 2014, the proportion fell from 39 percent to 30 percent. However, the absolute number of people living in slums went from 792 million in 2000 to an estimated 880 million in 2014. Movement from rural to urban areas has accelerated as the population has grown and better housing alternatives are available.[60]

Goal 12: Responsible consumption and production

"Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns."[61]

The targets of Goal 12 include using eco-friendly production methods and reducing the amount of waste. By 2030, national recycling rates should increase, as measured in tons of material recycled. Further, companies should adopt sustainable practices and publish sustainability reports.

Target 12.1 calls for the implementation of the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production.[62] This framework, adopted by member states at the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, is a global commitment to accelerate the shift to sustainable consumption and production in developed and developing countries.[63] In order to generate the collective impact necessary for such a shift, programs such as the One Planet Network have formed different implementation methods to help achieve Goal 12.[64]

Goal 13: Climate action

"Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts by regulating emissions and promoting developments in renewable energy."[65]

The UN discussions and negotiations identified the links between the post-2015 SDG process and the Financing for Development process that concluded in Addis Ababa in July 2015 and the COP 21 Climate Change conference in Paris in December 2015.[66]

In May 2015, a report concluded that only a very ambitious climate deal in Paris in 2015 could enable countries to reach the sustainable development goals and targets.[67] The report also states that tackling climate change will only be possible if the SDGs are met. Further, economic development and climate change are inextricably linked, particularly around poverty, gender equality, and energy. The UN encourages the public sector to take initiative in this effort to minimize negative impacts on the environment.[68]

This renewed emphasis on climate change mitigation was made possible by the partial Sino-American convergence that developed in 2015-2016, notably at the UN COP21 summit (Paris) and ensuing G20 conference (Hangzhou).[53]

At a 2017 UN Press Briefing, Global CEO Alliance (GCEOA) Chairman James Donovan described the Asia-Pacific region, which is a region particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, as needing more public-private partnerships (PPPs) to successfully implement its sustainable development initiatives.[69]

In 2018, the International Panel of Climate Change (IPCC),[70] the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change, published a special report "Global Warming of 1.5°C"[71]. It outlined the impacts of a 1.5 °C global temperature rise above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, and highlighted the possibility of avoiding a number of such impacts by limiting global warming to 1.5 °C compared to 2 °C, or more. The report mentioned that this would require global net human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) to fall by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching "net zero" around 2050, through “rapid and far-reaching” transitions in land, energy, industry, buildings, transport, and cities.[72] This special report was subsequently discussed at COP 24. Despite being requested by countries at the COP 21, the report was not accepted by four countries – the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Kuwait, which only wanted to "note" it, thereby postponing the resolution to the next SBSTA session in 2019.[73]

Goal 14: Life below water

"Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development."[74]

Sustainable Development Goal 14 aims “to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.”[75] Effective strategies to mitigate adverse effects of increased ocean acidification are needed to advance the sustainable use of oceans. As areas of protected marine biodiversity expand, there has been an increase in ocean science funding, essential for preserving marine resources.[76] The deterioration of coastal waters has become a global occurrence, due to pollution and coastal eutrophication (overflow of nutrients in water), where similar contributing factors to climate change can affect oceans and negatively impact marine biodiversity. “Without concerted efforts, coastal eutrophication is expected to increase in 20 per cent of large marine ecosystems by 2050.”[77]

The Preparatory Meeting to the UN Ocean Conference convened in New York, US, in February 2017, to discuss the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14. International law, as reflected in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), stressed the need to include governance instruments to consider “anthropogenic activities taking place outside of the ocean”.[78] Concerns regarding ocean health in destructive fishing practices and marine pollution were discussed, in looking at the role of local communities of small island developing States (SIDS) and least developed countries (LDCs) to not forget that oceans are a large part of their economies.[78] The targets include preventing and reducing marine pollution and acidification, protecting marine and coastal ecosystems, and regulating fishing. The targets also call for an increase in scientific knowledge of the oceans.[79][80]

Although many participating United Nations legislative bodies comes together to discuss the issues around marine environments and SDG 14, such as at the United Nations Ocean Conference, it is important to consider how SDG 14 is implemented across different Multilateral Environmental Agreements, respectively. As climate, biodiversity and land degradation are major parts of the issues surrounding the deterioration of marine environments and oceans, it is important to know how each Rio Convention implements this SDG.

Oceans cover 71 percent of the Earth's surface. They are essential for making the planet livable. Rainwater, drinking water and climate are all regulated by ocean temperatures and currents. Over 3 billion people depend on marine life for their livelihood. Oceans absorb 30 percent of all carbon dioxide produced by humans.[81] The oceans contain more than 200,000 identified species, and there might be thousands of species that are yet to be discovered. Oceans are the world's largest sources of protein. However, there has been a 26 percent increase in acidification since the industrial revolution. A full 30 percent of marine habitats have been destroyed, and 30 percent of the world's fish stocks are over-exploited.[81] Marine pollution has reached shocking levels; each minute, 15 tons of plastic are released into the oceans.[82] 20 percent of all coral reefs have been destroyed irreversibly, and another 24 percent are in immediate risk of collapse.[83] Approximately 1 million sea birds, 100 000 marine mammals, and an unknown number of fish are harmed or die annually due to marine pollution caused by humans. It has been found that 95 percent of fulmars in Norway have plastic parts in their guts.[82] Microplastics are another form of marine pollution.

Individuals can help the oceans by reducing their energy consumption and their use of plastics. Nations can also take action. In Norway, for instance, citizens, working through a web page called finn.no, can earn money for picking up plastic on the beach.[84] Several countries, including Kenya and Tanzania, have banned the use of plastic bags for retail purchases.[85][86] Improving the oceans contributes to poverty reduction, as it gives low-income families a source of income and healthy food. Keeping beaches and ocean water clean in less developed countries can attract tourism, as stated in Goal 8, and reduce poverty by providing more employment.[83]

Characterized by extinctions, invasions, hybridizations and reductions in the abundance of species, marine biodiversity is currently in global decline.[87] “Over the past decades, there has been an exponential increase in human activates in and near oceans, resulting in negative consequences to our marine environment.”[88] Made evident by the degradation of habitats and changes in ecosystem processes,[87] the declining health of the oceans has a negative effect on people, their livelihoods and entire economies, with local communities which rely on ocean resources being the most affected.[88] Poor decisions in resource management can compromise conservation, local livelihood, and resource sustainability goals.[89] “The sustainable management of our oceans relies on the ability to influence and guide human use of the marine environment.”[90] As conservation of marine resources is critical to the well-being of local fishing communities and their livelihoods, related management actions may lead to changes in human behavior to support conservation programs to achieve their goals.[91] Ultimately, governments and international agencies act as gatekeepers, interfering with needed stakeholder participation in decision making.[92] The way to best safeguard life in oceans is to implement effective management strategies around marine environments.[76]

Climate action is used as a way of protecting the world's oceans. Oceans cover three quarters of the Earth's surface and impact global climate systems through functions of carbon dioxide absorption from the atmosphere and oxygen generation. The increase in levels of greenhouse gases leading to changes in climate negatively affects the world's oceans and marine coastal communities. The resulting impacts of rising sea levels by 20 centimeters since the start of the 20th century and the increase of ocean acidity by 30% since the Industrial Revolution has contributed to the melting of ice sheets through the thermal expansion of sea water.[93]

Sustainable Development Goal 14 has been incorporated into the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD),[94] the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),[95] and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).[96]

Goal 15: Life on land

"Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss."[97]

This goal articulates targets for preserving biodiversity of forest, desert, and mountain eco-systems, as a percentage of total land mass. Achieving a "land degradation-neutral world" can be reached by restoring degraded forests and land lost to drought and flood. Goal 15 calls for more attention to preventing invasion of introduced species and more protection of endangered species.[98] Forests have a prominent role to play in the success of Agenda 2030, notably in terms of ecosystem services, livelihoods, and the green economy; but this will require clear priorities to address key tradeoffs and mobilize synergies with other SDGs.[99]

The Mountain Green Cover Index monitors progress toward target 15.4, which focuses on preserving mountain ecosystems. The index is named as the indicator for target 15.4.[100] Similarly, the Red Index (Red List Index or RLI) will fill the monitoring function for biodiversity goals by documenting the trajectory of endangered species.[98] Animal extinction is a growing problem.

Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions

"Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels."[101]

Reducing violent crime, sex trafficking, forced labor, and child abuse are clear global goals. The International Community values peace and justice and calls for stronger judicial systems that will enforce laws and work toward a more peaceful and just society. By 2017, the UN could report progress on detecting victims of trafficking. More women and girls than men and boys were victimized, yet the share of women and girls has slowly declined (see also violence against women). In 2004, 84 percent of victims were females and by 2014 that number had dropped to 71 percent. Sexual exploitation numbers have declined, but forced labor has increased.

One target is to see the end to sex trafficking, forced labor, and all forms of violence against and torture of children. However, reliance on the indicator of "crimes reported" makes monitoring and achieving this goal challenging.[102] For instance, 84 percent of countries have no or insufficient data on violent punishment of children.[29] Of the data available, it is clear that violence against children by their caregivers remains pervasive: Nearly 8 in 10 children aged 1 to 14 are subjected to violent discipline on a regular basis (regardless of income), and no country is on track to eliminate violent discipline by 2030.[29]

SDG 16 also targets universal legal identity and birth registration, ensuring the right to a name and nationality, civil rights, recognition before the law, and access to justice and social services. With more than a quarter of children under 5 unregistered worldwide as of 2015, about 1 in 5 countries will need to accelerate progress to achieve universal birth registration by 2030.[29]

Goal 17: Partnerships for the goals

"Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development."[103]

Increasing international cooperation is seen as vital to achieving each of the 16 previous goals. Goal 17 is included to assure that countries and organizations cooperate instead of compete. Developing multi-stakeholder partnerships to share knowledge, expertise, technology, and financial support is seen as critical to overall success of the SDGs. The goal encompasses improving North-South and South-South cooperation, and public-private partnerships which involve civil societies are specifically mentioned.[104]

Allocation

In 2019 five progress reports on the 17 SDGs appeared. Three came from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), one from the Bertelsmann Foundation and one from the European Union.[105][106][107][108] According to a review of the five reports in a synopsis, the allocation of the Goals and themes by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics, the allocation was the following:[109]

| SDG Topic | Rank | Average Rank | Mentions[Note 1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 1 | 3.2 | 1814 |

| Energy Climate Water |

2 | 4.0 | 1328 1328 1784 |

| Education | 3 | 4.6 | 1351 |

| Poverty | 4 | 6.2 | 1095 |

| Food | 5 | 7.6 | 693 |

| Economic Growth | 6 | 8.6 | 387 |

| Technology | 7 | 8.8 | 855 |

| Inequality | 8 | 9.2 | 296 |

| Gender Equality | 9 | 10.0 | 338 |

| Hunger | 10 | 10.6 | 670 |

| Justice | 11 | 10.8 | 328 |

| Governance | 12 | 11.6 | 232 |

| Decent Work | 13 | 12.2 | 277 |

| Peace | 14 | 12.4 | 282 |

| Clean Energy | 15 | 12.6 | 272 |

| Life on Land | 16 | 14.4 | 250 |

| Life below Water | 17 | 15.0 | 248 |

| Social Inclusion | 18 | 16.4 | 22 |

In explanation of the findings, the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics said Biodiversity, Peace and Social Inclusion were "left behind" by quoting the official SDGs motto "Leaving no one behind".[109]

Cross-cutting issues

_1.jpg)

Three sectors need to come together in order to achieve sustainable development. These are the economic, socio-political, and environmental sectors in their broadest sense.[110] This requires the promotion of multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary research across different sectors, which can be difficult, particularly when major governments fail to support it.[110]

According to the UN, the target is to reach the community farthest behind. Commitments should be transformed into effective actions requiring a correct perception of target populations. However, numerical and non-numerical data or information must address all vulnerable groups such as children, elderly folks, persons with disabilities, refugees, indigenous peoples, migrants, and internally-displaced persons.[111]

Women and gender equality

There is widespread consensus that progress on all of the SDGs will be stalled if women's empowerment and gender equality are not prioritized holistically – by policy makers as well as private sector executives and board members.[112][113]

Statements from diverse sources, such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), UN Women and the World Pensions Forum have noted that investments in women and girls have positive impacts on economies. National and global development investments often exceed their initial scope.[114]

Education and sustainable development

Education for sustainable development (ESD) is explicitly recognized in the SDGs as part of Target 4.7 of the SDG on education. UNESCO promotes the Global Citizenship Education (GCED) as a complementary approach.[115] At the same time, it is important to emphasize ESD's importance for all the other 16 SDGs. With its overall aim to develop cross-cutting sustainability competencies in learners, ESD is an essential contribution to all efforts to achieve the SDGs. This would enable individuals to contribute to sustainable development by promoting societal, economic and political change as well as by transforming their own behavior.[116]

Education, gender and technology

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) are free open education offered through online platforms. The (initial) philosophy of MOOCs was to open up quality Higher Education to a wider audience. As such, MOOCs are an important tool to achieve Goal 4 ("Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all").[117] At the same time, MOOCs also contribute to Goal 5, in that they are gender neutral and can give women and girls improved access to education.[117]

SDG-driven investment

Capital stewardship is expected to play a crucial part in the progressive advancement of the SDG agenda:

- "No longer absentee landlords', pension fund trustees have started to exercise more forcefully their governance prerogatives across the boardrooms of Britain, Benelux and America: coming together through the establishment of engaged pressure groups [...] to shift the [whole economic] system towards sustainable investment"[118] by using the SDG framework across all asset classes.[113]

In 2018 and early 2019, the World Pensions Council held a series of ESG-focused discussions with pension board members (trustees) and senior investment executives from across G20 nations in Toronto, London (with the UK Association of Member-Nominated Trustees, AMNT), Paris and New York – notably on the sidelines of the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly. Many pension investment executives and board members confirmed they were in the process of adopting or developing SDG-informed investment processes, with more ambitious investment governance requirements – notably when it comes to Climate Action, Gender Equity and Social Fairness: “they straddle key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including, of course, Gender Equality (SDG 5) and Reduced Inequality (SDG 10) […] Many pension trustees are now playing for keeps”.[119]

Implementation and support

.jpg)

Implementation of the SDGs started worldwide in 2016. This process can also be called "Localizing the SDGs". All over the planet, individual people, universities, governments and institutions and organizations of all kinds work on several goals at the same time.[120] In each country, governments must translate the goals into national legislation, develop a plan of action, establish budgets and at the same time be open to and actively search for partners. Poor countries need the support of rich countries and coordination at the international level is crucial.[121]

The independent campaign "Project Everyone" has met some resistance.[122][123] In addition, several sections of civil society and governments felt the SDGs ignored "sustainability" even though it was the most important aspect of the agreement.[124]

A 2018 study in the journal Nature found that while "nearly all African countries demonstrated improvements for children under 5 years old for stunting, wasting, and underweight... much, if not all of the continent will fail to meet the Sustainable Development Goal target—to end malnutrition by 2030".[32]

There have been two books produced one by each of the co-chairs of the negotiations to help people to understand the Sustainable Development Goals and where they came from: "Negotiating the Sustainable Development Goals: A transformational agenda for an insecure world" written by Ambassador David Donoghue, Felix Dodds and Jimena Leiva as well as "Transforming Multilateral Diplomacy: The Inside Story of the Sustainable Development Goals" by Macharia Kamau, David O'Connor and Pamela Chasek.

Tracking progress

The online publication SDG-Tracker was launched in June 2018 and presents data across all available indicators. It relies on the Our World in Data database and is also based at the University of Oxford.[125][126] The publication has global coverage and tracks whether the world is making progress towards the SDGs.[127] It aims to make the data on the 17 goals available and understandable to a wide audience.[5]

The website "allows people around the world to hold their governments accountable to achieving the agreed goals".[125] The SDG-Tracker highlights that the world is currently (early 2019) very far away from achieving the goals.

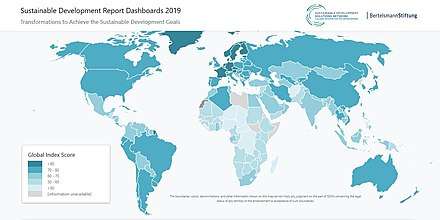

The Global SDG Index and Dashboards Report is the first publication to track countries' performance on all 17 Sustainable Development Goals.[128] The annual publication, co-produced by Bertelsmann Stiftung and SDSN, includes a ranking and dashboards that show key challenges for each country in terms of implementing the SDGs. The publication features trend analysis to show how countries performing on key SDG metrics has changed over recent years in addition to an analysis of government efforts to implement the SDGs.

At country level

United States

193 governments including the United States ratified the SDGs. However, the UN reported minimal progress after three years within the 15-year timetable of this project. Funding remains trillions of dollars short. The United States stand last among the G20 nations to attain these Sustainable Development Goals and 36th worldwide.[129]

United Kingdom

The UK's approach to delivering the Global SDGs is outlined in Agenda 2030: Delivering the Global Goals, developed by the Department for International Development. In 2019, the Bond network analysed the UK's global progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[130] The Bond report highlights crucial gaps where attention and investment are most needed. The report was compiled by 49 organisations and 14 networks and working groups.

Europe and Russia

Baltic nations, via the Council of the Baltic Sea States, have created the Baltic 2030 Action Plan.[131]

The World Pensions Forum has observed that UK and European Union pension investors have been at the forefront of ESG-driven (Environmental, Social and Governance) asset allocation at home and abroad and early adopters of "SDG-centric" investment practices.[113]

India

The Government of India established the NITI Aayog to attain the sustainable development goals.[132] In March 2018 Haryana became the first state in India to have its annual budget focused on the attainment of SDG with a 3-year action plan and a 7-year strategy plan to implement sustainable development goals when Captain Abhimanyu, Finance Minister of Government of Haryana, unveiled a ₹1,151,980 lakh (US$1.7 billion or €1.5 billion) annual 2018-19 budget.[133] Also, NITI Aayog starts the exercise of measuring India and its States’ progress towards the SDGs for 2030, culminating in the development of the first SDG India Index - Baseline Report 2018[134]

Bangladesh

Bangladesh publishes the Development Mirror to track progress towards the 17 goals.[135]

Bhutan

The Sustainable development process in Bhutan has a more meaningful purpose than economic growth alone. The nation's holistic goal is the pursuit of Gross National Happiness (GNH),[136] a term coined in 1972 by the Fourth King of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, which has the principal guiding philosophy for the long term journey as a nation. Therefore, the SDGs find a natural and spontaneous place within the framework of GNH sharing a common vision of prosperity, peace, and harmony where no one is left behind. Just as GNH is both an ideal to be pursued and a practical tool so too the SDGs inspire and guide sustainable action. Guided by the development paradigm of GNH, Bhutan is committed to achieving the goals of SDGs by 2030 since its implementation in September 2015. In line with Bhutan's commitment to the implementation of the SDGs and sustainable development, Bhutan has participated in the Voluntary National Review in the 2018 High-Level Political Forum.[137] As the country has progressed in its 12th Five year plan (2019-2023), the national goals have been aligned with the SDGs and every agency plays a vital role in its own ways to collectively achieving the committed goals of SDGs.

Public engagement

UN agencies which are part of the United Nations Development Group decided to support an independent campaign to communicate the new SDGs to a wider audience. This campaign, "Project Everyone," had the support of corporate institutions and other international organizations.[122]

Using the text drafted by diplomats at the UN level, a team of communication specialists developed icons for every goal.[138] They also shortened the title "The 17 Sustainable Development Goals" to "Global Goals/17#GlobalGoals," then ran workshops and conferences to communicate the Global Goals to a global audience.[139][140][141]

An early concern was that 17 goals would be too much for people to grasp and that therefore the SDGs would fail to get a wider recognition. That without wider recognition the necessary momentum to achieve them by 2030 would not be archived. Concerned with this, British film-maker Richard Curtis started the organization in 2015 called Project Everyone with the aim to bring the goals to everyone on the planet.[142][143][144] Curtis approached Swedish designer Jakob Trollbäck who rebranded them as The Global Goals and created the 17 iconic visuals with clear short names as well as a logotype for the whole initiative. The communication system is available for free.[145] In 2018 Jakob Trollbäck and his company The New Division went on to extend the communication system to also include the 169 targets that describe how the goals can be achieved.[146]

Film festivals

Le Temps Presse festival

The annual "Le Temps Presse" festival in Paris utilizes cinema to sensitize the public, especially young people, to the Sustainable Development Goals. The origin of the festival was in 2010 when eight directors produced a film titled "8," which included eight short films, each featuring one of the Millennium Development Goals. After 2.5 million viewers saw "8" on YouTube, the festival was created. It now showcases young directors whose work promotes social, environmental and human commitment. The festival now focuses on the Sustainable Development Goals.[147]

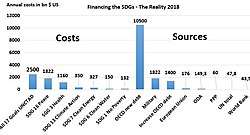

Costs and sources of finance

The Rockefeller Foundation asserts that "The key to financing and achieving the SDGs lies in mobilizing a greater share of the $200+ trillion in annual private capital investment flows toward development efforts, and philanthropy has a critical role to play in catalyzing this shift."[150] Large-scale funders participating in a Rockefeller Foundation-hosted design thinking workshop (June 2017: Scaling Solutions) were realistic. They concluded that "while there is a moral imperative to achieve the SDGs, failure is inevitable if there aren't drastic changes to how we go about financing large scale change".[151]

The Economist estimated that alleviating poverty and achieving the other sustainable development goals will require about US$2–3 trillion per year for the next 15 years which they called "pure fantasy".[152] Estimates for providing clean water and sanitation for the whole population of all continents have been as high as US$200 billion.[153] The World Bank says that estimates need to be made country by country, and reevaluated frequently over time.[153]

In 2014, UNCTAD estimated the annual costs to achieving the UN Goals at $2.5 trillion per year.[154]

In 2017 the UN launched the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development (UN IATF on FfD) that invited to a public dialogue.[155] In a policy paper, delivered by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics, that conducts the World Social Capital Monitor, a UN SDG Partnership Initiative, the following figures on both the costs and the major sources to finance the SDGs have been published by the UN IATF on FfD:[156]

| Costs | Source | |

| All 17 Goals UNCTAD | 2,500 | |

| SDG 16 Peace | 1,822 | |

| SGG 3 Health | 1,160 | |

| SDG 13 Climate Action | 350 | |

| SDG 7 Clean Energy | 327 | |

| SDG 6 Clean Water | 150 | |

| SDG 1 No Poverty | 132 | |

| OECD new debt (2018) | 10,500 | |

| Military spending worldwide (2018) | 1,822 | |

| Increase OECD debt (2018) | 1,400 | |

| European Union budget (2018) | 176 | |

| Official development assistance (2018) | 149.3 | |

| Public–private partnerships (2018) | 60 | |

| UN total budget (2018) | 47.8 | |

| World Bank budget (2018) | 43.5 |

Criticisms

The SDGs have been criticized for setting contradictory goals and for trying to do everything first, instead of focusing on the most urgent or fundamental priorities. The SDGs were an outcome from a UN conference that was not criticized by any major non-governmental organization (NGO). Instead, the SDGs received broad support from many NGOs.[157]

Competing goals

Some of the goals compete with each other. For example, seeking high levels of quantitative GDP growth can make it difficult to attain ecological, inequality reduction, and sustainability objectives. Similarly, increasing employment and wages can work against reducing the cost of living.

Continued global economic growth of 3 percent (Goal 8) may not be reconcilable with ecological sustainability goals, because the required rate of absolute global eco-economic decoupling is far higher than any country has achieved in the past.[158] Anthropologists have suggested that, instead of targeting aggregate GDP growth, the goals could target resource use per capita, with "substantial reductions in high‐income nations."[158]

Too many goals

A commentary in The Economist in 2015 argued that 169 targets for the SDGs is too many, describing them as "sprawling, misconceived" and "a mess".[152] The goals are said to ignore local context. All other 16 goals might be contingent on achieving SDG 1, ending poverty, which should have been at the top of a very short list of goals. In addition, Bhargava (2019) has emphasized the inter-dependence between the numerous sub-goals and the role played by population growth in developing countries in hampering their operationalization.

On the other hand, nearly all stakeholders engaged in negotiations to develop the SDGs agreed that the high number of 17 goals was justified because the agenda they address is all-encompassing.

Weak on environmental sustainability

Environmental constraints and planetary boundaries are underrepresented within the SDGs. For instance, the paper "Making the Sustainable Development Goals Consistent with Sustainability[159]" points out that the way the current SDGs are structured leads to a negative correlation between environmental sustainability and SDGs. This means, as the environmental sustainability side of the SDGs is underrepresented, the resource security for all, particularly for lower-income populations, is put at risk. This is not a criticism of the SDGs per se, but a recognition that their environmental conditions are still weak.[158]

Comparison with Millennium Development Goals

A commentary in The Economist in 2015 said that the SDGs are "a mess" compared to the eight MDGs used previously.[152] The MDGs were about development while the SDGs are about sustainable development. Finally, the MDGs used a sole approach to problems, while the SDGs take into account the inter-connectedness of all the problems.

Whilst the MDGs were strongly criticized by many NGOs as only dealing with the problems, the SDGs deal with the causes of the problems. Another core feature of the SDGs is their focus on means of implementation, or the mobilization of financial resources, along with capacity building and technology.

See also

- Action for Climate Empowerment

- Economics of climate change mitigation

- Education 2030 Agenda

- Planetary management

- Social Progress Index

- Sustainable Development Goals and Iran

Further reading

Bhargava, A. (2019). "Climate change, demographic pressures and global sustainability", Economics and Human Biology, 33, 149-154.

Lietaer, Bernard (2019). "Towards a sustainable world - 3 paradigms to achieve", available as of Oct.31, 2019 ISBN 978-3-200-06527-7. Discusses "the law of sustainability" presented with Robert E.Ulanowicz and Sally J.Goerner.

Wilson, Clive (2018). "Designing the Purposeful World - the Sustainable Development Goals as a blueprint for humanity" Routledge

Sources

![]()

![]()

Notes

- While the total ranking results on the average ranking in five different reports, the number of mentions is not identical with the average ranking.

References

- Sachs, J., Schmidt-Traub, G., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G. (2019): Sustainable Development Report 2019. New York: Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN)

- dpicampaigns. "About the Sustainable Development Goals". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "United Nations Official Document". www.un.org.

- "Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development". United Nations – Sustainable Development knowledge platform. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- "17Goals – The SDG Tracker: Charts, graphs and data at your fingertips". Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "The History of Sustainable Development in the United Nations". Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development. UN. 20–22 June 2012. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Development, World Commission on Environment and. "Our Common Future, Chapter 2: Towards Sustainable Development - A/42/427 Annex, Chapter 2 - UN Documents: Gathering a body of global agreements". www.un-documents.net. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Caballero, Paula (29 April 2016). "A Short History of the SDGs" (PDF). Deliver 2030. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017.

- "Future We Want – Outcome document .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". Sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "New Open Working Group to Propose Sustainable Development Goals for Action by General Assembly's Sixty-eighth Session | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". Un.org. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Home .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". Sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "United Nations Official Document". Un.org. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Secretary-General's remarks to the press at COP22". UN. 15 November 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- UN Task Team on the Post 2015 Agenda (March 2013). "Report of the UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda". United Nations. p. 1. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- "United Nations Official Document". Un.org. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "World leaders adopt Sustainable Development Goals". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Breakdown of U.N. Sustainable Development Goals". Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "Technical report by the Bureau of the United Nations Statistical Commission (UNSC) on the process of the development of an indicator framework for the goals and targets of the post-2015 development agenda – working draft" (PDF). March 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "SDG Indicators. Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development". Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "United Nations General Assembly Draft outcome document of the United Nations summit for the adoption of the post-2015 development agenda". UN. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Goal 1: No poverty". UNDP. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "PovcalNet". iresearch.worldbank.org. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Commission on Global Poverty". World Bank. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Thewissen, Stefan; Ncube, Mthuli; Roser, Max; Sterck, Olivier (1 February 2018). "Allocation of development assistance for health: is the predominance of national income justified?". Health Policy and Planning. 33 (suppl_1): i14–i23. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw173. ISSN 0268-1080. PMC 5886300. PMID 29415236.

- "Extreme poverty is falling: How is poverty changing for higher poverty lines?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Roser, Max (25 May 2013). "Global Extreme Poverty". Our World in Data.

- "Progress For Every Child in the SDG Era" (PDF). Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Goal 2: Zero hunger". UNDP. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "Progress for Every Child in the SDG Era" (PDF). UNICEF. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "From Promise to Impact: Ending malnutrition by 2030" (PDF). UNICEF. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Fan, Shenggen and Polman, Paul. 2014. An ambitious development goal: Ending hunger and undernutrition by 2025. In 2013 Global food policy report. Eds. Marble, Andrew and Fritschel, Heidi. Chapter 2. Pp 15-28. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Osgood-Zimmerman, Aaron; Millear, Anoushka I.; Stubbs, Rebecca W.; Shields, Chloe; Pickering, Brandon V.; Earl, Lucas; Graetz, Nicholas; Kinyoki, Damaris K.; Ray, Sarah E. (2018). "Mapping child growth failure in Africa between 2000 and 2015". Nature. 555 (7694): 41–47. doi:10.1038/nature25760. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 6346257. PMID 29493591.

- "Goal 3: Good health and well-being". UNDP. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "WHO - UN Sustainable Development Summit 2015". WHO.

- "Goal 4: Quality education". UNDP. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "Education : Number of out-of-school children of primary school age". data.uis.unesco.org. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Goal 5: Gender equality". UNDP. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "United Nations: Gender equality and women's empowerment". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Sustainable Development Goal 5: Gender equality". UN Women. UN Women. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- "Goal 05. Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls – Indicators and a Monitoring Framework". indicators.report. indicators.report. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- Leach, Anna (2 June 2015). "21 ways the SDGs can have the best impact on girls". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- Firzli, Nicolas (3 April 2018). "Greening, Governance and Growth in the Age of Popular Empowerment". FT Pensions Experts. Financial Times. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation". UNDP. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Goal 6 Targets". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- WHO and UNICEF (2017) Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2017

- Kellogg, Diane M. (2017). "The Global Sanitation Crisis: A Role for Business". Beyond the bottom line: integrating sustainability into business and management practice. Gudić, Milenko, Tan, Tay Keong, Flynn, Patricia M. Saltaire, UK: Greenleaf Publishing. ISBN 9781783533275. OCLC 982187046.

- "SDGs". Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Vision". Sustainable Sanitation Alliance. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Contribution of sustainable sanitation to the Agenda 2030 for sustainable development - SuSanA Vision Document 2017". SuSanA, Eschborn, Germany. 2017. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017.

- "Sustainable sanitation and the SDGs: interlinkages and opportunities". Sustainable Sanitation Alliance Knowledge Hub. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Goal 7: Affordable and clean energy". UNDP. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (October 2016). "Beyond SDGs: Can Fiduciary Capitalism and Bolder, Better Boards Jumpstart Economic Growth?". Analyse Financière. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- "Goal 9: Industry, innovation, infrastructure". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Progress of Goal 9 in 2017". Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Goal 10: Reduced inequalities". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "What We Do". World Bank. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Progress of Goal 10 in 2017". Sustainable Development Goal Knowledge Platform. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Sustainable Development Goal 11". Sustainable Development Goals. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Goal 12: Responsible consumption, production". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Goal 12 .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "A/CONF.216/5: A 10-Year Framework of Programmes" (PDF).

- http://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/platform-sustainable-development-goal-12 Retrieved October 15, 2018

- "Goal 13: Climate action". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Paris Climate Change Conference: COP21". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Ansuategi, A; Greño, P; Houlden, V; et al. (May 2015). "The impact of climate change on the achievement of the post-2015 sustainable development goals" (PDF). CDKN & HR Wallingford. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- "Sustainable Development Innovation Briefs, Issue 9". March 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2016 – via UN.org.

- "GCEOA Chairman Underscores the Value of Big Data for the SDGS" (Press release). Global CEO Alliance (GCEOA). 23 May 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "IPCC — Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Global Warming of 1.5 ºC —". Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Summary for Policymakers of IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C approved by governments — IPCC". Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "COP24: Key outcomes agreed at the UN climate talks in Katowice". Carbon Brief. 16 December 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Goal 14: Life below water". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018". UN Stats. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019.

- "Goal 14 .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- United Nations (2018). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018.

- Covert, J. (2017). Planning for the Implementation of SDG-14. Environmental Policy & Law, 47(1), 6–8. doi:10.3233/EPL-170003

- "Goal 14: Life below water". UNDP.

- "Life Below Water: Why It Matters" (PDF).

- UNDP2017

- WWF2017

- UN2016

- Tesdal Galtung, Anders; Rolfsnes, May-Helen (13 July 2017). "Finn.no kjøper sekker med havplast". NRK. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Kenya plastic bag ban comes into force after years of delays". BBC News. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "You will no longer carry plastic bags in Tanzania with effect". The Citizen. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Staples, D., & Hermes, R. (2012). Marine biodiversity and resource management – what is the link? Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management, 15(3), 245–252. doi:10.1080/14634988.2012.709429

- Vierros, M. (2017). Global Marine Governance and Oceans Management for the Achievement of SDG 14. UN Chronicle, 54(1/2), 1. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=123355527&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Metcalfe, K., Collins, T., Abernethy, K. E., Boumba, R., Dengui, J., Miyalou, R., … Godley, B. J. (2017). Addressing Uncertainty in Marine Resource Management; Combining Community Engagement and Tracking Technology to Characterize Human Behavior. Conservation Letters, 10(4), 459–469. doi:10.1111/conl.12293

- van Putten, I. E., Plagányi, É. E., Booth, K., Cvitanovic, C., Kelly, R., Punt, A. E., & Richards, S. A. (2018). A framework for incorporating sense of place into the management of marine systems. Ecology & Society, 23(4), 42–65. doi:10.5751/ES-10504-230404

- Hughes, Z. D., Fenichel, E. P., & Gerber, L. R. (2011). The Potential Impact of Labor Choices on the Efficacy of Marine Conservation Strategies. PLoS ONE, 6(8), 1–10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023722

- Finkl, C. W., & Makowski, C. (2010). Increasing sustainability of coastal management by merging monitored marine environments with inventoried shelf resources. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 67(6), 861–870. doi:10.1080/00207230902916786

- "Climate Action is Needed to Protect World's Oceans | UNFCCC". unfccc.int. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- CBD (2019). Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Retrieved from https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/

- "Ocean Climate Action Making Waves | UNFCCC". unfccc.int. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Land and Sustainable Development Goals | UNCCD". www.unccd.int. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Goal 15: Life on land". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Sustainable Development Goal 12". Sustainable Development UN. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Timko, Joleen (2018). "A policy nexus approach to forests and the SDGs: tradeoffs and synergies". Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 34: 7–12. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.06.004.

- "Mountain Partnership: working together for mountain peoples and environment". Mountain Partnership. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "SDG16 Data Initiative 2017 Global Report". SDG16 Report. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Goal 17: Partnerships for the goals". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Sustainable Development Goal 17". Sustainable Development Goals. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019" (PDF).

- "Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2019 | United Nations".

- "The future is now: Science for archiving sustanable development" (PDF).

- "Sustainable development in the European Union". Eurostat.

- "Leaving Biodiversity, Peace and Social Inclusion behind" (PDF). Basel Institute of Commons and Economics.

- "Sustainable Development Goals 2016-2030: Easier Stated Than Achieved – JIID". 21 August 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- "Leaving no one behind — SDG Indicators". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Firzli, Nicolas (5 April 2017). "6th World Pensions Forum held at the Queen's House: ESG and Asset Ownership" (PDF). Revue Analyse Financière. Revue Analyse Financière. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- Firzli, Nicolas (3 April 2018). "Greening, Governance and Growth in the Age of Popular Empowerment". FT Pensions Experts. Financial Times. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "Gender equality and women's rights in the post-2015 agenda: A foundation for sustainable development" (PDF). Oecd.org. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- Global Citizenship Education: Topics and learning objectives, UNESCO, 2015.

- UNESCO (2017). Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. p. 7. ISBN 978-92-3-100209-0.

- Patru, Mariana; Balaji, Venkataraman (2016). Making Sense of MOOCs: A Guide for Policy-Makers in Developing Countries (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-92-3-100157-4.

- Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (October 2016). "Beyond SDGs: Can Fiduciary Capitalism and Bolder, Better Boards Jumpstart Economic Growth?". Analyse Financiere. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- Firzli, Nicolas (7 December 2018). "An Examination of Pensions Trends. On Balance, How Do Things Look?". BNPSS Newsletter. BNP Paribas Securities Services. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Belay Begashaw (16 April 2017). "Global governance for SDGs". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- "Project Everyone". Project-everyone.org. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Why this is Sustainable Development Not Global Goals – Africa Platform". Africaplatform.org. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Public SDGs or Private GGs? – Global Policy Watch". Globalpolicywatch.org. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Ritchie, Roser, Mispy, Ortiz-Ospina. "Measuring progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals." SDG-Tracker.org, website (2018).

- Hub, IISD's SDG Knowledge. "SDG-Tracker.org Releases New Resources | News | SDG Knowledge Hub | IISD". Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Eerste 'tracker' die progressie op SDG's per land volgt | Fondsnieuws". www.fondsnieuws.nl. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- SDSN; Bertelsmann Stiftung. "SDG Index". SDG Index and Dashboards Report. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Sustainable Development Solutions Network | Ahead of G20 Summit: 'My Country First' Approach Threatens Achievement of Global Goals". Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "The UK's global contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals - Progress, gaps and recommendations". Bond. 17 June 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Sustainable Development – Baltic 2030". cbss.org. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Business in India keen: delegation, Dec 2017.

- [Haryana Budget 2018 Presented by Captain Abhimanyu: Highlights Haryana Budget 2018 Presented by Captain Abhimanyu: Highlights], India.com, 9 Mar 2018.

- SDG India Index – Baseline Report 2018.

- "SDG Tracker: Portals". www.sdg.gov.bd. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- https://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/

- https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/memberstates/bhutan

- "The "post 2015" = 17 Sustainable Development Goals or 17#GlobalGoals 2015-2020-2030 - MyAgenda21.tk". sites.google.com.

- "the-new-division". the-new-division. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "How This Great Design Is Bringing World Change to the Masses". GOOD Magazine. 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "Global Festival of Action – Global Festival of Action". globalfestivalofideas.org. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- https://www.project-everyone.org/ Project Everyone

- Hub, IISD's SDG Knowledge. "Guest Article: Making the SDGs Famous and Popular - SDG Knowledge Hub - IISD".

- "PROJECT EVERYONE - Overview (free company information from Companies House)". beta.companieshouse.gov.uk.

- "Resources". The Global Goals.

- "The New Division". www.thenewdivision.world.

- "Le Temps Presse". Le Temps Presse. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "Arctic Film Festival". FilmFreeway. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- "The Arctic Film Festival - United Nations Partnerships for SDGs platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Madsbjerg, Saadia (19 September 2017). "A New Role for Foundations in Financing the Global Goals". Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Burgess, Cameron (March 2018). "From Billions to Trillions: Mobilising the Missing Trillions to Solve the Sustainable Development Goals". sphaera.world. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- "The 169 commandments". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Hutton, Guy (15 November 2017). "The Costs of Meeting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal Targets on Drinking Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene" (PDF). Documents/World Bank. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "UNCTAD | Press Release". unctad.org. Retrieved 8 December 2019.