Health equity

Health equity synonymous with health disparity refers to the study and causes of differences in the quality of health and healthcare across different populations.[1] Health equity is different from health equality, as it refers only to the absence of disparities in controllable or remediable aspects of health. It is not possible to work towards complete equality in health, as there are some factors of health that are beyond human influence.[2] Inequity implies some kinds of social injustice. Thus, if one population dies younger than another because of genetic differences, a non-remediable/controllable factor, we tend to say that there is a health inequality. On the other hand, if a population has a lower life expectancy due to lack of access to medications, the situation would be classified as a health inequity.[3] These inequities may include differences in the "presence of disease, health outcomes, or access to health care"[4] between populations with a different race, ethnicity, sexual orientation or socioeconomic status.[5]

Health equity falls into two major categories: horizontal equity, the equal treatment of individuals or groups in the same circumstances; and vertical equity, the principle that individuals who are unequal should be treated differently according to their level of need.[6] Disparities in the quality of health across populations are well-documented globally in both developed and developing nations. The importance of equitable access to healthcare has been cited as crucial to achieving many of the Millennium Development Goals.[7]

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status is both a strong predictor of health, and a key factor underlying health inequities across populations. Poor socioeconomic status has the capacity to profoundly limit the capabilities of an individual or population, manifesting itself through deficiencies in both financial and social capital.[8] It is clear how a lack of financial capital can compromise the capacity to maintain good health. In the UK, prior to the institution of the NHS reforms in the early 2000s, it was shown that income was an important determinant of access to healthcare resources.[9] Because one's job or career is a primary conduit for both financial and social capital, work is an important, yet under represented, factor in health inequities research and prevention efforts.[10] Maintenance of good health through the utilization of proper healthcare resources can be quite costly and therefore unaffordable to certain populations.[11][12][13]

In China, for instance, the collapse of the Cooperative Medical System left many of the rural poor uninsured and unable to access the resources necessary to maintain good health.[14] Increases in the cost of medical treatment made healthcare increasingly unaffordable for these populations. This issue was further perpetuated by the rising income inequality in the Chinese population. Poor Chinese were often unable to undergo necessary hospitalization and failed to complete treatment regimens, resulting in poorer health outcomes.[15]

Similarly, in Tanzania, it was demonstrated that wealthier families were far more likely to bring their children to a healthcare provider: a significant step towards stronger healthcare.[16] Some scholars have noted that unequal income distribution itself can be a cause of poorer health for a society as a result of "underinvestment in social goods, such as public education and health care; disruption of social cohesion and the erosion of social capital".[13]

The role of socioeconomic status in health equity extends beyond simple monetary restrictions on an individual's purchasing power. In fact, social capital plays a significant role in the health of individuals and their communities. It has been shown that those who are better connected to the resources provided by the individuals and communities around them (those with more social capital) live longer lives.[17] The segregation of communities on the basis of income occurs in nations worldwide and has a significant impact on quality of health as a result of a decrease in social capital for those trapped in poor neighborhoods.[11][18][19][20][21] Social interventions, which seek to improve healthcare by enhancing the social resources of a community, are therefore an effective component of campaigns to improve a community's health. A 1998 epidemiological study showed that community healthcare approaches fared far better than individual approaches in the prevention of heart disease mortality.[22]

Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty used by some programs in the developing world appear to lead to a reduction in the likelihood of being sick.[23] Such evidence can guide resource allocations to effective interventions.

Education

Education is an important factor in healthcare utilization, though it is closely intertwined with economic status. An individual may not go to a medical professional or seek care if they don’t know the ills of their failure to do so, or the value of proper treatment.[24] In Tajikistan, since the nation gained its independence, the likelihood of giving birth at home has increased rapidly among women with lower educational status. Education also has a significant impact on the quality of prenatal and maternal healthcare. Mothers with primary education consulted a doctor during pregnancy at significantly lower rates (72%) when compared to those with a secondary education (77%), technical training (88%) or a higher education (100%).[25] There is also evidence for a correlation between socioeconomic status and health literacy; one study showed that wealthier Tanzanian families were more likely to recognize disease in their children than those that were coming from lower income backgrounds.[16]

Spatial disparities in health

For some populations, access to healthcare and health resources is physically limited, resulting in health inequities. For instance, an individual might be physically incapable of traveling the distances required to reach healthcare services, or long distances can make seeking regular care unappealing despite the potential benefits.[24]

Costa Rica, for example, has demonstrable health spatial inequities with 12–14% of the population living in areas where healthcare is inaccessible. Inequity has decreased in some areas of the nation as a result of the work of healthcare reform programs, however those regions not served by the programs have experienced a slight increase in inequity.[26]

China experienced a serious decrease in spatial health equity following the Chinese economic revolution in the 1980s as a result of the degradation of the Cooperative Medical System (CMS). The CMS provided an infrastructure for the delivery of healthcare to rural locations, as well as a framework to provide funding based upon communal contributions and government subsidies. In its absence, there was a significant decrease in the quantity of healthcare professionals (35.9%), as well as functioning clinics (from 71% to 55% of villages over 14 years) in rural areas, resulting in inequitable healthcare for rural populations.[21][27] The significant poverty experienced by rural workers (some earning less than 1 USD per day) further limits access to healthcare, and results in malnutrition and poor general hygiene, compounding the loss of healthcare resources.[15] The loss of the CMS has had noticeable impacts on life expectancy, with rural regions such as areas of Western China experiencing significantly lower life expectancies.[28][29]

Similarly, populations in rural Tajikistan experience spatial health inequities. A study by Jane Falkingham noted that physical access to healthcare was one of the primary factors influencing quality of maternal healthcare. Further, many women in rural areas of the country did not have adequate access to healthcare resources, resulting in poor maternal and neonatal care. These rural women were, for instance, far more likely to give birth in their homes without medical oversight.[25]

Ethnic and racial disparities

Along with the socioeconomic factor of health disparities, race is another key factor. The United States historically had large disparities in health and access to adequate healthcare between races, and current evidence supports the notion that these racially centered disparities continue to exist and are a significant social health issue.[30][31] The disparities in access to adequate healthcare include differences in the quality of care based on race and overall insurance coverage based on race. A 2002 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association identifies race as a significant determinant in the level of quality of care, with blacks receiving lower quality care than their white counterparts.[32] This is in part because members of ethnic minorities such as African Americans are either earning low incomes, or living below the poverty line. In a 2007 Census Bureau, African American families made an average of $33,916, while their white counterparts made an average of $54,920.[33] Due to a lack of affordable health care, the African American death rate reveals that African Americans have a higher rate of dying from treatable or preventable causes. According to a study conducted in 2005 by the Office of Minority Health—a U.S. Department of Health—African American men were 30% more likely than white men to die from heart disease.[33] Also African American women were 34% more likely to die from breast cancer than their white counterparts.[33]

There are also considerable racial disparities in access to insurance coverage, with ethnic minorities generally having less insurance coverage than non-ethnic minorities. For example, Hispanic Americans tend to have less insurance coverage than white Americans and as a result receive less regular medical care. The level of insurance coverage is directly correlated with access to healthcare including preventative and ambulatory care.[30] A 2010 study on racial and ethnic disparities in health done by the Institute of Medicine has shown that the aforementioned disparities cannot solely be accounted for in terms of certain demographic characteristics like: insurance status, household income, education, age, geographic location and quality of living conditions. Even when the researchers corrected for these factors, the disparities persist.[34] Slavery has contributed to disparate health outcomes for generations of African Americans in the United States.[35]

Ethnic health inequities also appear in nations across the African continent. A survey of the child mortality of major ethnic groups across 11 African nations (Central African Republic, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Uganda, and Zambia) was published in 2000 by the WHO. The study described the presence of significant ethnic parities in the child mortality rates among children younger than 5 years old, as well as in education and vaccine use.[36] In South Africa, the legacy of apartheid still manifests itself as a differential access to social services, including healthcare based upon race and social class, and the resultant health inequities.[37][38] Further, evidence suggests systematic disregard of indigenous populations in a number of countries. The Pygmys of Congo, for instance, are excluded from government health programs, discriminated against during public health campaigns, and receive poorer overall healthcare.[39]

In a survey of five European countries (Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, Italy, and France), a 1995 survey noted that only Sweden provided access to translators for 100% of those who needed it, while the other countries lacked this service potentially compromising healthcare to non-native populations. Given that non-natives composed a considerable section of these nations (6%, 17%, 3%, 1%, and 6% respectively), this could have significant detrimental effects on the health equity of the nation. In France, an older study noted significant differences in access to healthcare between native French populations, and non-French/migrant populations based upon health expenditure; however this was not fully independent of poorer economic and working conditions experienced by these populations.[40]

A 1996 study of race-based health inequity in Australia revealed that Aborigines experienced higher rates of mortality than non-Aborigine populations. Aborigine populations experienced 10 times greater mortality in the 30–40 age range; 2.5 times greater infant mortality rate, and 3 times greater age standardized mortality rate. Rates of diarrheal diseases and tuberculosis are also significantly greater in this population (16 and 15 times greater respectively), which is indicative of the poor healthcare of this ethnic group. At this point in time, the parities in life expectancy at birth between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples were highest in Australia, when compared to the US, Canada and New Zealand.[41][42] In South America, indigenous populations faced similarly poor health outcomes with maternal and infant mortality rates that were significantly higher (up to 3 to 4 times greater) than the national average.[43] The same pattern of poor indigenous healthcare continues in India, where indigenous groups were shown to experience greater mortality at most stages of life, even when corrected for environmental effects.[44]

LGBT health disparities

Sexuality is a basis of health discrimination and inequity throughout the world. Homosexual, bisexual, transgender, and gender-variant populations around the world experience a range of health problems related to their sexuality and gender identity,[45][46][47][48] some of which are complicated further by limited research.

In spite of recent advances, LGBT populations in China, India, and Chile continue to face significant discrimination and barriers to care.[48][49][50] The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that there is inadequate research data about the effects of LGBT discrimination on morbidity and mortality rates in the patient population. In addition, retrospective epidemiological studies on LGBT populations are difficult to conduct as a result of the practice that sexual orientation is not noted on death certificates.[51] WHO has proposed that more research about the LGBT patient population is needed for improved understanding of its unique health needs and barriers to accessing care.[52]

Recognizing the need for LGBT healthcare research, the Director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services designated sexual and gender minorities (SGMs) as a health disparity population for NIH research in October 2016.[53] For the purposes of this designation, the Director defines SGM as "encompass[ing] lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations, as well as those whose sexual orientation, gender identity and expressions, or reproductive development varies from traditional, societal, cultural, or physiological norms".[53] This designation has prioritized research into the extent, cause, and potential mitigation of health disparities among SGM populations within the larger LGBT community.

While many aspects of LGBT health disparities are heretofore uninvestigated, at this stage, it is known that one of the main forms of healthcare discrimination LGBT individuals face is discrimination from healthcare workers or institutions themselves.[54][55] A systematic literature review of publications in English and Portuguese from 2004–2014 demonstrate significant difficulties in accessing care secondary to discrimination and homophobia from healthcare professionals.[56] This discrimination can take the form of verbal abuse, disrespectful conduct, refusal of care, the withholding of health information, inadequate treatment, and outright violence.[56][57] In a study analyzing the quality of healthcare for South African men who have sex with men (MSM), researchers interviewed a cohort of individuals about their health experiences, finding that MSM who identified as homosexual felt their access to healthcare was limited due to an inability to find clinics employing healthcare workers who did not discriminate against their sexuality.[58] They also reportedly faced "homophobic verbal harassment from healthcare workers when presenting for STI treatment".[58] Further, MSM who did not feel comfortable disclosing their sexual activity to healthcare workers failed to identify as homosexuals, which limited the quality of the treatment they received.[58]

Additionally, members of the LGBT community contend with health care disparities due, in part, to lack of provider training and awareness of the population’s healthcare needs.[57] Transgender individuals believe that there is a higher importance of providing gender identity (GI) information more than sexual orientation (SO) to providers to help inform them of better care and safe treatment for these patients.[59] Studies regarding patient-provider communication in the LGBT patient community show that providers themselves report a significant lack of awareness regarding the health issues LGBT-identifying patients face.[57] As a component of this fact, medical schools do not focus much attention on LGBT health issues in their curriculum; the LGBT-related topics that are discussed tend to be limited to HIV/AIDS, sexual orientation, and gender identity.[57]

Among LGBT-identifying individuals, transgender individuals face especially significant barriers to treatment. Many countries still do not have legal recognition of transgender or non-binary gender individuals leading to placement in mis-gendered hospital wards and medical discrimination.[60][61] Seventeen European states mandate sterilization of individuals who seek recognition of a gender identity that diverges from their birth gender.[61] In addition to many of the same barriers as the rest of the LGBT community, a WHO bulletin points out that globally, transgender individuals often also face a higher disease burden.[62] A 2010 survey of transgender and gender-variant people in the United States revealed that transgender individuals faced a significant level of discrimination.[63] The survey indicated that 19% of individuals experienced a healthcare worker refusing care because of their gender, 28% faced harassment from a healthcare worker, 2% encountered violence, and 50% saw a doctor who was not able or qualified to provide transgender-sensitive care.[63] In Kuwait, there have been reports of transgender individuals being reported to legal authorities by medical professionals, preventing safe access to care.[60] An updated version of the U.S. survey from 2015 showed little change in terms of healthcare experiences for transgender and gender variant individuals. The updated survey revealed that 23% of individuals reported not seeking necessary medical care out of fear of discrimination, and 33% of individuals who had been to a doctor within a year of taking the survey reported negative encounters with medical professionals related to their transgender status.[64]

The stigmatization represented particularly in the transgender population creates a health disparity for LGBT individuals with regard to mental health.[54] The LGBT community is at increased risk for psychosocial distress, mental health complications, suicidality, homelessness, and substance abuse, often complicated by access-based under-utilization or fear of health services.[54][55][65] Transgender and gender-variant individuals have been found to experience higher rates of mental health disparity than LGB individuals. According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, for example, 39% of respondents reported serious psychological distress, compared to 5% of the general population.[64]

These mental health facts are informed by a history of anti-LGBT bias in health care.[66] The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) listed homosexuality as a disorder until 1973; transgender status was listed as a disorder until 2012.[66] This was amended in 2013 with the DSM-5 when "gender identity disorder" was replaced with "gender dysphoria", reflecting that simply identifying as transgender is not itself pathological and that the diagnosis is instead for the distress a transgender person may experience as a result of the discordance between assigned gender and gender identity.[67]

LGBT health issues have received disproportionately low levels of medical research, leading to difficulties in assessing appropriate strategies for LGBT treatment. For instance, a review of medical literature regarding LGBT patients revealed that there are significant gaps in the medical understanding of cervical cancer in lesbian and bisexual individuals[51] it is unclear whether its prevalence in this community is a result of probability or some other preventable cause. For example, LGBT people report poorer cancer care experiences.[68] It is incorrectly assumed that LGBT women have a lower incidence of cervical cancer than their heterosexual counterparts, resulting in lower rates of screening.[51] Such findings illustrate the need for continued research focused on the circumstances and needs of LGBT individuals and the inclusion in policy frameworks of sexual orientation and gender identity as social determinants of health.[69]

A June 2017 review sponsored by the European commission as part of a larger project to identify and diminish health inequities, found that LGB are at higher risk of some cancers and that LGBTI were at higher risk of mental illness, and that these risks were not adequately addressed. The causes of health inequities were, according to the review, "i) cultural and social norms that preference and prioritise heterosexuality; ii) minority stress associated with sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics; iii) victimisation; iv) discrimination (individual and institutional), and; v) stigma."[70]

Sex and gender in healthcare equity

Sex and gender in medicine

Both gender and sex are significant factors that influence health. Sex is characterized by female and male biological differences in regards to gene expression, hormonal concentration, and anatomical characteristics.[71] Gender is an expression of behavior and lifestyle choices. Both sex and gender inform each other, and it is important to note that differences between the two genders influence disease manifestation and associated healthcare approaches.[71] Understanding how the interaction of sex and gender contributes to disparity in the context of health allows providers to ensure quality outcomes for patients. This interaction is complicated by the difficulty of distinguishing between sex and gender given their intertwined nature; sex modifies gender, and gender can modify sex, thereby impacting health.[71] Sex and gender can both be considered sources of health disparity; both contribute to men and women’s susceptibility to various health conditions, including cardiovascular disease and autoimmune disorders.[71]

Health disparities in the male population

As sex and gender are inextricably linked in day-to-day life, their union is apparent in medicine. Gender and sex are both components of health disparity in the male population. In non-Western regions, males tend to have a health advantage over women due to gender discrimination, evidenced by infanticide, early marriage, and domestic abuse for females.[72] In most regions of the world, the mortality rate is higher for adult men than for adult women; for example, adult men suffer from fatal illnesses with more frequency than females.[73] The leading causes of the higher male death rate are accidents, injuries, violence, and cardiovascular diseases. In a number of countries, males also face a heightened risk of mortality as a result of behavior and greater propensity for violence.[73]

Physicians tend to offer invasive procedures to male patients more than female patients.[74] Furthermore, men are more likely to smoke than women and experience smoking-related health complications later in life as a result; this trend is also observed in regard to other substances, such as marijuana, in Jamaica, where the rate of use is 2–3 times more for men than women.[73] Lastly, men are more likely to have severe chronic conditions and a lower life expectancy than women in the United States.[75]

Health disparities in the female population

Gender and sex are also components of health disparity in the female population. The 2012 World Development Report (WDR) noted that women in developing nations experience greater mortality rates than men in developing nations.[76] Additionally, women in developing countries have a much higher risk of maternal death than those in developed countries. The highest risk of dying during childbirth is 1 in 6 in Afghanistan and Sierra Leone, compared to nearly 1 in 30,000 in Sweden—a disparity that is much greater than that for neonatal or child mortality.[77]

While women in the United States tend to live longer than men, they generally are of lower socioeconomic status (SES) and therefore have more barriers to accessing healthcare.[78] Being of lower SES also tends to increase societal pressures, which can lead to higher rates of depression and chronic stress and, in turn, negatively impact health.[78] Women are also more likely than men to suffer from sexual or intimate-partner violence both in the United States and worldwide. In Europe, women who grew up in poverty are more likely to have lower muscle strength and higher disability in old age.[79][80]

Women have better access to healthcare in the United States than they do in many other places in the world.[81] In one population study conducted in Harlem, New York, 86% of women reported having privatized or publicly assisted health insurance, while only 74% of men reported having any health insurance. This trend is representative of the general population of the United States.[82]

In addition, women's pain tends to be treated less seriously and initially ignored by clinicians when compared to their treatment of men's pain complaints.[83] Historically, women have not been included in the design or practice of clinical trials, which has slowed the understanding of women's reactions to medications and created a research gap. This has led to post-approval adverse events among women, resulting in several drugs being pulled from the market. However, the clinical research industry is aware of the problem, and has made progress in correcting it.[84][85]

Cultural factors

Health disparities are also due in part to cultural factors that involve practices based not only on sex, but also gender status. For example, in China, health disparities have distinguished medical treatment for men and women due to the cultural phenomenon of preference for male children.[86] Recently, gender-based disparities have decreased as females have begun to receive higher-quality care.[87][88] Additionally, a girl’s chances of survival are impacted by the presence of a male sibling; while girls do have the same chance of survival as boys if they are the oldest girl, they have a higher probability of being aborted or dying young if they have an older sister.[89]

In India, gender-based health inequities are apparent in early childhood. Many families provide better nutrition for boys in the interest of maximizing future productivity given that boys are generally seen as breadwinners.[90] In addition, boys receive better care than girls and are hospitalized at a greater rate. The magnitude of these disparities increases with the severity of poverty in a given population.[91]

Additionally, the cultural practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) is known to impact women's health, though is difficult to know the worldwide extent of this practice. While generally thought of as a Sub-Saharan African practice, it may have roots in the Middle East as well.[92] The estimated 3 million girls who are subjected to FGM each year potentially suffer both immediate and lifelong negative effects.[93] Immediately following FGM, girls commonly experience excessive bleeding and urine retention.[94] Long-term consequences include urinary tract infections, bacterial vaginosis, pain during intercourse, and difficulties in childbirth that include prolonged labor, vaginal tears, and excessive bleeding.[95][96] Women who have undergone FGM also have higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV2) than women who have not.[97][98]

Health inequality and environmental influence

Minority populations have increased exposure to environmental hazards that include lack of neighborhood resources, structural and community factors as well as residential segregation that result in a cycle of disease and stress.[99] The environment that surrounds us can influence individual behaviors and lead to poor health choices and therefore outcomes.[100] Minority neighborhoods have been continuously noted to have more fast food chains and fewer grocery stores than predominantly white neighborhoods.[100] These food deserts affect a family’s ability to have easy access to nutritious food for their children. This lack of nutritious food extends beyond the household into the schools that have a variety of vending machines and deliver over processed foods.[100] These environmental condition have social ramifications and in the first time in US history is it projected that the current generation will live shorter lives than their predecessors will.[100]

In addition, minority neighborhoods have various health hazards that result from living close to highways and toxic waste factories or general dilapidated structures and streets.[100] These environmental conditions create varying degrees of health risk from noise pollution, to carcinogenic toxic exposures from asbestos and radon that result in increase chronic disease, morbidity, and mortality.[101] The quality of residential environment such as damaged housing has been shown to increase the risk of adverse birth outcomes, which is reflective of a communities health.[102] Housing conditions can create varying degrees of health risk that lead to complications of birth and long-term consequences in the aging population.[102] In addition, occupational hazards can add to the detrimental effects of poor housing conditions. It has been reported that a greater number of minorities work in jobs that have higher rates of exposure to toxic chemical, dust and fumes.[103]

Racial segregation is another environmental factor that occurs through the discriminatory action of those organizations and working individuals within the real estate industry, whether in the housing markets or rentals. Even though residential segregation is noted in all minority groups, blacks tend to be segregated regardless of income level when compared to Latinos and Asians.[104] Thus, segregation results in minorities clustering in poor neighborhoods that have limited employment, medical care, and educational resources, which is associated with high rates of criminal behavior.[105][106] In addition, segregation affects the health of individual residents because the environment is not conducive to physical exercise due to unsafe neighborhoods that lack recreational facilities and have nonexistent park space.[105] Racial and ethnic discrimination adds an additional element to the environment that individuals have to interact with daily. Individuals that reported discrimination have been shown to have an increase risk of hypertension in addition to other physiological stress related affects.[107] The high magnitude of environmental, structural, socioeconomic stressors leads to further compromise on the psychological and physical being, which leads to poor health and disease.[108]

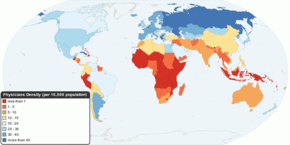

Individuals living in rural areas, especially poor rural areas, have access to fewer health care resources. Although 20 percent of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, only 9 percent of physicians practice in rural settings. Individuals in rural areas typically must travel longer distances for care, experience long waiting times at clinics, or are unable to obtain the necessary health care they need in a timely manner. Rural areas characterized by a largely Hispanic population average 5.3 physicians per 10,000 residents compared with 8.7 physicians per 10,000 residents in nonrural areas. Financial barriers to access, including lack of health insurance, are also common among the urban poor.[109]

Disparities in access to health care

Reasons for disparities in access to health care are many, but can include the following:

- Lack of universal health care or health insurance coverage. Without health insurance, patients are more likely to postpone medical care, go without needed medical care, go without prescription medicines, and be denied access to care.[110] Minority groups in the United States lack insurance coverage at higher rates than whites.[111] This problem does not exist in countries with fully funded public health systems, such as the examplar of the NHS.

- Lack of a regular source of care. Without access to a regular source of care, patients have greater difficulty obtaining care, fewer doctor visits, and more difficulty obtaining prescription drugs. Compared to whites, minority groups in the United States are less likely to have a doctor they go to on a regular basis and are more likely to use emergency rooms and clinics as their regular source of care.[112] In the United Kingdom, which is much more racially harmonious, this issue arises for a different reason; since 2004, NHS GPs have not been responsible for care out of normal GP surgery opening hours, leading to significantly higher attendances in A+E

- Lack of financial resources. Although the lack of financial resources is a barrier to health care access for many Americans, the impact on access appears to be greater for minority populations.[113]

- Legal barriers. Access to medical care by low-income immigrant minorities can be hindered by legal barriers to public insurance programs. For example, in the United States federal law bars states from providing Medicaid coverage to immigrants who have been in the country fewer than five years.[114] Another example could be when a non-English speaking person attends a clinic where the receptionist does not speak the person's language. This is mostly seen in Hispanic people who do not speak English.

- Structural barriers. These barriers include poor transportation, an inability to schedule appointments quickly or during convenient hours, and excessive time spent in the waiting room, all of which affect a person's ability and willingness to obtain needed care.[115]

- The health care financing system. The Institute of Medicine in the United States says fragmentation of the U.S. health care delivery and financing system is a barrier to accessing care. Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to be enrolled in health insurance plans which place limits on covered services and offer a limited number of health care providers.[114]

- Scarcity of providers. In inner cities, rural areas, and communities with high concentrations of minority populations, access to medical care can be limited due to the scarcity of primary care practitioners, specialists, and diagnostic facilities.[116] In the UK, Monitor (a quango) has a legal obligation to ensure that sufficient provision exists in all parts of the nation.

- Linguistic barriers. Language differences restrict access to medical care for minorities in the United States who are not English-proficient.[117]

- Health literacy. This is where patients have problems obtaining, processing, and understanding basic health information. For example, patients with a poor understanding of good health may not know when it is necessary to seek care for certain symptoms. While problems with health literacy are not limited to minority groups, the problem can be more pronounced in these groups than in whites due to socioeconomic and educational factors.[116] A study conducted in Mdantsane, South Africa depicts the correlation of maternal education and the antenatal visits for pregnancy. As patients have a greater education, they tend to use maternal health care services more than those with a lesser maternal education background.[118]

- Lack of diversity in the health care workforce. A major reason for disparities in access to care are the cultural differences between predominantly white health care providers and minority patients. Only 4% of physicians in the United States are African American, and Hispanics represent just 5%, even though these percentages are much less than their groups' proportion of the United States population.[119]

- Age. Age can also be a factor in health disparities for a number of reasons. As many older Americans exist on fixed incomes which may make paying for health care expenses difficult. Additionally, they may face other barriers such as impaired mobility or lack of transportation which make accessing health care services challenging for them physically. Also, they may not have the opportunity to access health information via the internet as less than 15% of Americans over the age of 65 have access to the internet.[120] This could put older individuals at a disadvantage in terms of accessing valuable information about their health and how to protect it. On the other hand, older individuals in the US (65 or above) are provided with medical care via Medicare.

Disparities in quality of health care

Health disparities in the quality of care exist and are based on language and ethnicity/race which includes:

Problems with patient-provider communication

Communication is critical for the delivery of appropriate and effective treatment and care, regardless of a patient’s race, and miscommunication can lead to incorrect diagnosis, improper use of medications, and failure to receive follow-up care. The patient provider relationship is dependent on the ability of both individuals to effectively communicate. Language and culture both play a significant role in communication during a medical visit. Among the patient population, minorities face greater difficulty in communicating with their physicians. Patients when surveyed responded that 19% of the time they have problems communicating with their providers which included understanding doctor, feeling doctor listened, and had questions but did not ask.[121] In contrast, the Hispanic population had the largest problem communicating with their provider, 33% of the time.[121] Communication has been linked to health outcomes, as communication improves so does patient satisfaction which leads to improved compliance and then to improved health outcomes.[122] Quality of care is impacted as a result of an inability to communicate with health care providers. Language plays a pivotal role in communication and efforts need to be taken to ensure excellent communication between patient and provider. Among limited English proficient patients in the United States, the linguistic barrier is even greater. Less than half of non-English speakers who say they need an interpreter during clinical visits report having one. The absence of interpreters during a clinical visit adds to the communication barrier. Furthermore, inability of providers to communicate with limited English proficient patients leads to more diagnostic procedures, more invasive procedures, and over prescribing of medications.[123] Language barriers have not only hindered appointment scheduling, prescription filling, and clear communications, but have also been associated with health declines, which can be attributed to reduced compliance and delays in seeking care, which could affect particularly refugee health in the United States. [124][125] Many health-related settings provide interpreter services for their limited English proficient patients. This has been helpful when providers do not speak the same language as the patient. However, there is mounting evidence that patients need to communicate with a language concordant physician (not simply an interpreter) to receive the best medical care, bond with the physician, and be satisfied with the care experience.[126][127] Having patient-physician language discordant pairs (i.e. Spanish-speaking patient with an English-speaking physician) may also lead to greater medical expenditures and thus higher costs to the organization.[128] Additional communication problems result from a decrease or lack of cultural competence by providers. It is important for providers to be cognizant of patients’ health beliefs and practices without being judgmental or reacting. Understanding a patients’ view of health and disease is important for diagnosis and treatment. So providers need to assess patients’ health beliefs and practices to improve quality of care.[129] Patient health decisions can be influenced by religious beliefs, mistrust of Western medicine, and familial and hierarchical roles, all of which a white provider may not be familiar with.[130] Other type of communication problems are seen in LGBT health care with the spoken heterosexist (conscious or unconscious) attitude on LGBT patients, lack of understanding on issues like having no sex with men (lesbians, gynecologic examinations) and other issues.[131]

Provider discrimination

Provider discrimination occurs when health care providers either unconsciously or consciously treat certain racial and ethnic patients differently from other patients. This may be due to stereotypes that providers may have towards ethnic/racial groups. Doctors are more likely to ascribe negative racial stereotypes to their minority patients.[132] This may occur regardless of consideration for education, income, and personality characteristics. Two types of stereotypes may be involved, automatic stereotypes or goal modified stereotypes. Automated stereotyping is when stereotypes are automatically activated and influence judgments/behaviors outside of consciousness.[133] Goal modified stereotype is a more conscious process, done when specific needs of clinician arise (time constraints, filling in gaps in information needed) to make a complex decisions.[133] Physicians are unaware of their implicit biases.[134] Some research suggests that ethnic minorities are less likely than whites to receive a kidney transplant once on dialysis or to receive pain medication for bone fractures. Critics question this research and say further studies are needed to determine how doctors and patients make their treatment decisions. Others argue that certain diseases cluster by ethnicity and that clinical decision making does not always reflect these differences.[135]

Lack of preventive care

According to the 2009 National Healthcare Disparities Report, uninsured Americans are less likely to receive preventive services in health care.[136] For example, minorities are not regularly screened for colon cancer and the death rate for colon cancer has increased among African Americans and Hispanic populations. Furthermore, limited English proficient patients are also less likely to receive preventive health services such as mammograms.[137] Studies have shown that use of professional interpreters have significantly reduced disparities in the rates of fecal occult testing, flu immunizations and pap smears.[138] In the UK, Public Health England, a universal service free at the point of use, which forms part of the NHS, offers regular screening to any member of the population considered to be in an at-risk group (such as individuals over 45) for major disease (such as colon cancer, or diabetic-retinopathy).[139][140]

Plans for achieving health equity

There are a multitude of strategies for achieving health equity and reducing disparities outlined in scholarly texts, some examples include:

- Advocacy. Advocacy for health equity has been identified as a key means of promoting favourable policy change.[141] EuroHealthNet carried out a systematic review of the academic and grey literature. It found, amongst other things, that certain kinds of evidence may be more persuasive in advocacy efforts, that practices associated with knowledge transfer and translation can increase the uptake of knowledge, that there are many different potential advocates and targets of advocacy and that advocacy efforts need to be tailored according to context and target.[142] As a result of its work, it produced an online advocacy for health equity toolkit.[143]

- Provider based incentives to improve healthcare for ethnic populations. One source of health inequity stems from unequal treatment of non-white patients in comparison with white patients. Creating provider based incentives to create greater parity between treatment of white and non-white patients is one proposed solution to eliminate provider bias.[144] These incentives typically are monetary because of its effectiveness in influencing physician behavior.

- Using Evidence Based Medicine (EBM). Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) shows promise in reducing healthcare provider bias in turn promoting health equity.[145] In theory EBM can reduce disparities however other research suggests that it might exacerbate them instead. Some cited shortcomings include EBM’s injection of clinical inflexibility in decision making and its origins as a purely cost driven measure.[146]

- Increasing awareness. The most cited measure to improving health equity relates to increasing public awareness. A lack of public awareness is a key reason why there has not been significant gains in reducing health disparities in ethnic and minority populations. Increased public awareness would lead to increased congressional awareness, greater availability of disparity data, and further research into the issue of health disparities.

- The Gradient Evaluation Framework. The evidence base defining which policies and interventions are most effective in reducing health inequalities is extremely weak. It is important therefore that policies and interventions which seek to influence health inequity be more adequately evaluated. Gradient Evaluation Framework (GEF) is an action-oriented policy tool that can be applied to assess whether policies will contribute to greater health equity amongst children and their families.[147]

- The AIM framework. In a pilot study, researchers examined the role of AIM—ability, incentives, and management feedback—in reducing care disparity in pressure-ulcer detection between African American and Caucasian residents. The results showed that while the program was implemented, the provision of (1) training to enhance ability, (2) monetary incentives to enhance motivation, and (3) management feedback to enhance accountability led to successful reduction in pressure ulcers. Specifically, the detection gap between the two groups decreased. The researchers suggested additional replications with longer duration to assess the effectiveness of the AIM framework.

- Monitoring actions on the social determinants of health. In 2017, citing the need for accountability for the pledges made by countries in the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health, the World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund called for the monitoring of intersectoral interventions on the social determinants of health that improve health equity.[148]

Health inequalities

Health inequality is the term used in a number of countries to refer to those instances whereby the health of two demographic groups (not necessarily ethnic or racial groups) differs despite comparative access to health care services. Such examples include higher rates of morbidity and mortality for those in lower occupational classes than those in higher occupational classes, and the increased likelihood of those from ethnic minorities being diagnosed with a mental health disorder. In Canada, the issue was brought to public attention by the LaLonde report.

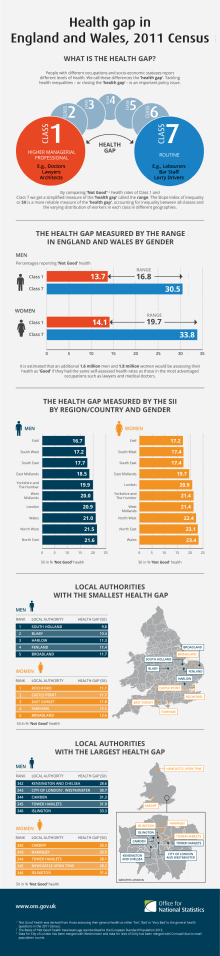

In UK, the Black Report was produced in 1980 to highlight inequalities. On 11 February 2010, Sir Michael Marmot, an epidemiologist at University College London, published the Fair Society, Healthy Lives report on the relationship between health and poverty. Marmot described his findings as illustrating a "social gradient in health": the life expectancy for the poorest is seven years shorter than for the most wealthy, and the poor are more likely to have a disability. In its report on this study, The Economist argued that the material causes of this contextual health inequality include unhealthful lifestyles - smoking remains more common, and obesity is increasing fastest, amongst the poor in Britain.[149]

In June 2018, the European Commission launched the Joint Action Health Equity in Europe.[150] Forty-nine participants from 25 European Union Member States will work together to address health inequalities and the underlying social determinants of health across Europe. Under the coordination of the Italian Institute of Public Health, the Joint Action aims to achieve greater equity in health in Europe across all social groups while reducing the inter-country heterogeneity in tackling health inequalities.

Poor health and economic inequality

Poor health outcomes appear to be an effect of economic inequality across a population. Nations and regions with greater economic inequality show poorer outcomes in life expectancy,[151] mental health,[152] drug abuse,[153] obesity,[154] educational performance, teenage birthrates, and ill health due to violence. On an international level, there is a positive correlation between developed countries with high economic equality and longevity. This is unrelated to average income per capita in wealthy nations.[155] Economic gain only impacts life expectancy to a great degree in countries in which the mean per capita annual income is less than approximately $25,000. The United States shows exceptionally low health outcomes for a developed country, despite having the highest national healthcare expenditure in the world. The US ranks 31st in life expectancy. Americans have a lower life expectancy than their European counterparts, even when factors such as race, income, diet, smoking, and education are controlled for.[156]

Relative inequality negatively affects health on an international, national, and institutional levels. The patterns seen internationally hold true between more and less economically equal states in the United States. The patterns seen internationally hold true between more and less economically equal states in the United States, that is, more equal states show more desirable health outcomes. Importantly, inequality can have a negative health impact on members of lower echelons of institutions. The Whitehall I and II studies looked at the rates of cardiovascular disease and other health risks in British civil servants and found that, even when lifestyle factors were controlled for, members of lower status in the institution showed increased mortality and morbidity on a sliding downward scale from their higher status counterparts. The negative aspects of inequality are spread across the population. For example, when comparing the United States (a more unequal nation) to England (a less unequal nation), the US shows higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, cancer, lung disease, and heart disease across all income levels.[157] This is also true of the difference between mortality across all occupational classes in highly equal Sweden as compared to less-equal England.[158]

See also

- Center for Minority Health

- Drift hypothesis

- EuroHealthNet

- Environmental justice

- Environmental racism

- Global Task Force on Expanded Access to Cancer Care and Control in Developing Countries

- Health Disparities Center

- Healthcare and the LGBT community

- Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions

- Immigrant paradox

- Inequality in disease

- Joint Action Health Equity in Europe

- Mental health inequality

- Population health

- Public health

- Social determinants of health

- Social determinants of health in poverty

- Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?

References

- "Glossary of a Few Key Public Health Terms". Office of Health Disparities, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- WHO | Equity. (n.d.). WHO. Retrieved February 27, 2014, from http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/

- Kawachi I., Subramanian S., Almeida-Filho N. "A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:647–652;56:647–652

- Goldberg, J., Hayes, W., and Huntley, J. "Understanding Health Disparities." Health Policy Institute of Ohio (November 2004), page 3.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Healthy People 2010: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives, conference ed. in two vols (Washington, D.C., January 2000).

- JAN. Economic Analysis For Management And Policy [e-book]. Open University Press; 2005 [cited 2013 Mar 21]. Available from: MyiLibrary. <http://lib.myilibrary.com?ID=95419>

- Vandemoortele, Milo (2010) The MDGs and equity Overseas Development Institute

- Ben-Shlomo Yoav, White Ian R., Marmot Michael (1996). "Does the Variation in the Socioeconomic Characteristics of an Area Affect Mortality?". BMJ. 312 (7037): 1013–1014. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7037.1013. PMC 2350820. PMID 8616348.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Morris S.; Sutton M.; Gravelle H. (2005). "Inequity and inequality in the use of health care in England: an empirical investigation". Social Science & Medicine. 60 (6): 1251–1266. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.07.016. PMID 15626522.

- Ahonen, Emily Quinn; Fujishiro, Kaori; Cunningham, Thomas; Flynn, Michael (2018-01-18). "Work as an Inclusive Part of Population Health Inequities Research and Prevention". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (3): 306–311. doi:10.2105/ajph.2017.304214. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 5803801. PMID 29345994.

- Kawachi I., Kennedy B. P. (1997). "Health and Social Cohesion: Why Care about Income Inequality?". BMJ. 314 (7086): 1037–1040. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7086.1037. PMC 2126438. PMID 9112854.

- Shi L; et al. (1999). "Income Inequality, Primary Care, and Health Indicators". The Journal of Family Practice. 48 (4): 275–284.

- Kawachi, I., & Kennedy, B. P. (1999). Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Services Research, 34(1 Pt 2), 215–227.

- Sun, X., Jackson, S., Carmichael, G. and Sleigh, A.C., 2009. Catastrophic medical payment and financial protection in rural China: evidence from the New Cooperative Medical Scheme in Shandong Province. Health economics, 18(1), pp.103-119.

- Zhao Zhongwei (2006). "Income Inequality, Unequal Health Care Access, and Mortality in China". Population and Development Review. 32 (3): 461–483. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00133.x.

- Schellenberg J. A.; Victora C. G.; Mushi A.; de Savigny D.; Schellenberg D.; Mshinda H.; Bryce J. (2003). "Inequities among the very poor: health care for children in rural southern Tanzania". The Lancet. 361 (9357): 561–566. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12515-9. PMID 12598141.

- House J. S., Landis K. R., Umberson D. (1988). "Social relationships and health". Science. 241 (4865): 540–545. Bibcode:1988Sci...241..540H. doi:10.1126/science.3399889.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Musterd S.; De Winter M. (1998). "Conditions for spatial segregation: some European perspectives". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 22 (4): 665–673. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00168.

- Musterd S (2005). "Social and Ethnic Segregation in Europe: Levels, Causes, and Effects". Journal of Urban Affairs. 27 (3): 331–348. doi:10.1111/j.0735-2166.2005.00239.x.

- Hajnal Z. L. (1995). "The Nature of Concentrated Urban Poverty in Canada and the United States". Canadian Journal of Sociology. 20 (4): 497–528. doi:10.2307/3341855. JSTOR 3341855.

- Kanbur, Ravi; Zhang, Xiaobo (2005). "Spatial inequality in education and health care in China". China Economic Review. 16 (2): 189–204. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2005.02.002.

- Lomas Jonathan (1998). "Social Capital and Health: Implications for Public Health and Epidemiology". Social Science & Medicine. 47 (9): 1181–1188. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.460.596. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00190-7.

- Pega, Frank; Liu, Sze; Walter, Stefan; Pabayo, Roman; Saith, Ruhi; Lhachimi, Stefan (2017). "Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD011135. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011135.pub2. PMC 6486161. PMID 29139110.

- Banerjee, A., Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2011). Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. PublicAffairs.

- Falkingham Jane (2003). "Inequality and Changes in Women's Use of Maternal Health-Care Services in Tajikistan". Studies in Family Planning. 34 (1): 32–43. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00032.x. PMID 12772444.

- Rosero-Bixby L (2004). "Spatial access to health care in Costa Rica and its equity: a GIS-based study". Social Science & Medicine. 58 (7): 1271–1284. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00322-8. PMID 14759675.

- Liu Y.; Hsiao W. C.; Eggleston K. (1999). "Equity in health and health care: the Chinese experience". Social Science & Medicine. 49 (10): 1349–1356. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00207-5.

- Qian Jiwei. (n.d.). Regional Inequality in Healthcare in China. East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore.

- Wang H, Xu T, Xu J (2007). "Factors Contributing to High Costs and Inequality in China's Health Care System". JAMA. 298 (16): 1928–1930. doi:10.1001/jama.298.16.1928. PMID 17954544.

- Weinick R. M.; Zuvekas S. H.; Cohen J. W. (2000). "Racial and ethnic differences in access to and use of health care services, 1977 to 1996. Medical care research and review". MCRR. 57 (Suppl 1): 36–54.

- Copeland, CS (Jul–Aug 2013). "Disparate Lives: Health Outcomes Among Ethnic Minorities in New Orleans" (PDF). Healthcare Journal of New Orleans: 10–16.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Schneider, Eric C. (2002-03-13). "Racial Disparities in the Quality of Care for Enrollees in Medicare Managed Care". JAMA. 287 (10): 1288. doi:10.1001/jama.287.10.1288. ISSN 0098-7484.

- "African American Poverty Leads to Health Disparities". Gale Virtual Reference Library. UXL. 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- Nelson A (2002). "Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care". Journal of the National Medical Association. 94: 8.

- Gaskins, Darrell J. (Spring 2005). "RACIAL DISPARITIES IN HEALTH AND WEALTH: THE EFFECTS OF SLAVERY AND PAST DISCRIMINATION". Review of Black Political Economy. 32 (America: History & Life, EBSCOhost): 95. doi:10.1007/s12114-005-1007-9.

- Brockerhoff, M; Hewett, P (2000). "Inequality of child mortality among ethnic groups in sub-Saharan Africa". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 78 (1): 30–41. PMC 2560588. PMID 10686731.

- Bloom G.; McIntyre D. (1998). "Towards equity in health in an unequal society". Social Science & Medicine. 47 (10): 1529–1538. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00233-0.

- McIntyre D.; Gilson L. (2002). "Putting equity in health back onto the social policy agenda: experience from South Africa". Social Science & Medicine. 54 (11): 1637–1656. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00332-X.

- Ohenjo N.; Willis R.; Jackson D.; Nettleton C.; Good K.; Mugarura B. (2006). "Health of Indigenous people in Africa". The Lancet. 367 (9526): 1937–1946. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68849-1. PMID 16765763.

- Bollini P.; Siem H. (1995). "No real progress towards equity: Health of migrants and ethnic minorities on the eve of the year 2000". Social Science & Medicine. 41 (6): 819–828. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)00386-8.

- Mooney G (1996). "And now for vertical equity? Some concerns arising from Aboriginal health in Australia". Health Economics. 5 (2): 99–103. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199603)5:2<99::AID-HEC193>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 8733102.

- Anderson I.; Crengle S.; Leialoha Kamaka M.; Chen T.-H.; Palafox N.; Jackson-Pulver L. (2006). "Indigenous health in Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific". The Lancet. 367 (9524): 1775–1785. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68773-4. PMID 16731273.

- Montenegro R. A.; Stephens C. (2006). "Indigenous health in Latin America and the Caribbean". The Lancet. 367 (9525): 1859–1869. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68808-9. PMID 16753489.

- Subramanian S. V.; Smith G. D.; Subramanyam M. (2006). "Indigenous Health and Socioeconomic Status in India". PLoS Med. 3 (10): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030421. PMC 1621109. PMID 17076556.

- Burke, Jill. "Understanding the GLBT community." ASHA Leader 20 Jan. 2009: 4+. Communications and Mass Media Collection.

- Gochman, David S. (1997). Handbook of health behavior research. Springer. pp. 145–147. ISBN 9780306454431

- Trettin S., Moses-Kolko E.L., Wisner K.L. (2006). "Lesbian perinatal depression and the heterosexism that affects knowledge about this minority population". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 9 (2): 67–73. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2328. PMC 3130513. PMID 21668380.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Burki, Talha (2017). "Health and rights challenges for China's LGBT community". The Lancet. 389 (10076): 1286. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30837-1. PMID 28379143.

- Brocchetto M. “Being gay in Latin America: Legal but deadly”. CNN. Updated March 3, 2017 http://www.cnn.com/2017/02/26/americas/lgbt-rights-in-the-americas/index.html. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- Soumya, Elizabeth Soumya Elizabeth. "Indian transgender healthcare challenges". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- Tracy, J. Kathleen; Lydecker, Alison D.; Ireland, Lynda (2010-01-24). "Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening Among Lesbians". Journal of Women's Health. 19 (2): 229–237. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1393. ISSN 1540-9996. PMC 2834453. PMID 20095905.

- CD52/18: Addressing the causes of disparities in health service access and utilization for lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) persons. 2013. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/populations/lgbt_paper/en/

- Meads, C.; Pennant, M.; McManus, J.; Bayliss, S. (2011). "A systematic review of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health in the West Midlands Region of the UK compared to published UK research". Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Kalra G.,Ventriglio A., Bhugra D. Sexuality and mental health: Issues and what next? (2015) International Review of Psychiatry Vol. 27 , Iss. 5.

- King, Michael; Semlyen, Joanna; Tai, Sharon See; Killaspy, Helen; Osborn, David; Popelyuk, Dmitri; Nazareth, Irwin (2008-08-18). "A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people". BMC Psychiatry. 8: 70. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. ISSN 1471-244X. PMC 2533652. PMID 18706118.

- Alencar Albuquerque, Grayce; de Lima Garcia, Cintia; da Silva Quirino, Glauberto; Alves, Maria Juscinaide Henrique; Belém, Jameson Moreira; dos Santos Figueiredo, Francisco Winter; da Silva Paiva, Laércio; do Nascimento, Vânia Barbosa; da Silva Maciel, Érika (2016-01-14). "Access to health services by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: systematic literature review". BMC International Health and Human Rights. 16: 2. doi:10.1186/s12914-015-0072-9. ISSN 1472-698X. PMC 4714514. PMID 26769484.

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Lane, T; Mogale, T; Struthers, H; McIntyre, J; Kegeles, S M (2008). ""They see you as a different thing": The experiences of men who have sex with men with healthcare workers in South African township communities". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 84 (6): 430–3. doi:10.1136/sti.2008.031567. PMC 2780345. PMID 19028941.

- Maragh-Bass, Allysha C.; Torain, Maya; Adler, Rachel; Ranjit, Anju; Schneider, Eric; Shields, Ryan Y.; Kodadek, Lisa M.; Snyder, Claire F.; German, Danielle (June 2017). "Is It Okay To Ask: Transgender Patient Perspectives on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Collection in Healthcare". Academic Emergency Medicine. 24 (6): 655–667. doi:10.1111/acem.13182. ISSN 1553-2712. PMID 28235242.

- "Rights in Transition". Human Rights Watch. 2016-01-06. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- "Transgender people face challenges for adequate health care: study". Reuters. 2016-06-17. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- Thomas Rebekah, Pega Frank, Khosla Rajat, Verster Annette, Hana Tommy, Say Lale (2017). "Ensuring an inclusive global health agenda for transgender people". World Health Organization. 95 (2): 154–156. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.183913. PMC 5327942. PMID 28250518.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jaime M. Grant, Lisa A. Mottet, & Justin Tanis. (2010). National Transgender Discrimination Survey Report on health and health care. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

- James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health". HealthyPeople.gov. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Understanding the Health Needs of LGBT People. (March 2016) National LGBT Health Education Center. The Fenway Institute.

- Parekh, Ranna (February 2016). "What Is Gender Dysphoria?". American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Hulbert-Williams, N. J.; Plumpton, C.o.; Flowers, P.; McHugh, R.; Neal, R.d.; Semlyen, J.; Storey, L. (2017-07-01). "The cancer care experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual patients: A secondary analysis of data from the UK Cancer Patient Experience Survey" (PDF). European Journal of Cancer Care. 26 (4): n/a. doi:10.1111/ecc.12670. ISSN 1365-2354. PMID 28239936.

- Pega, Frank; Veale, Jaimie (2015). "The case for the World Health Organization's Commission on Social Determinants of Health to address gender identity". American Journal of Public Health. 105 (3): e58–62. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302373. PMC 4330845. PMID 25602894.

- Health4LGBTI (June 2017). "State-of-the-art study focusing on the health inequalities faced by LGBTI people D1.1 State-of-the-Art Synthesis Report (SSR) June, 2017" (PDF).

- Regitz-Zagrosek, Vera (July 2012). "Sex and gender differences in health". EMBO Reports. 13 (7): 596–603. doi:10.1038/embor.2012.87. ISSN 1469-221X. PMC 3388783. PMID 22699937.

- Fikree, FF; Pasha, O (2004). "Role of gender in health disparity: the South Asian context". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 328 (7443): 823–826. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7443.823. PMC 383384. PMID 15070642.

- Barker, G. "What about boys? A literature review on the health and development of adolescent boys" (PDF). WHO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-04-11.

- Kent, Jennifer; Patel, Vinisha; Varela, Natalie (2012). "Gender Disparities in Healthcare". Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 79 (5): 555–559. doi:10.1002/msj.21336. PMID 22976361.

- Courtenay, Will H (2000-05-16). "Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health". Social Science & Medicine. 50 (10): 1385–1401. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.4452. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1.

- World Bank. (2012). World Development Report on Gender Equality and Development.

- Ronsmans, Carine; Graham, Wendy J (2006). "Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why". The Lancet. 368 (9542): 1189–1200. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69380-x. PMID 17011946.

- Read, Jen'nan Ghazal; Gorman, Bridget K. (2010). "Gender and Health Inequality". Annual Review of Sociology. 36 (1): 371–386. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102535.

- Cheval, Boris; et al. (2018-02-20). "Association of early- and adult-life socioeconomic circumstances with muscle strength in older age". Age and Ageing. 47 (3): 398–407. doi:10.1093/ageing/afy003. ISSN 0002-0729. PMID 29471364.

- Landös, Aljoscha; et al. (2018). "Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and disability trajectories in older men and women: a European cohort study". European Journal of Public Health. 29: 50–58. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky166. PMID 30689924.

- Vaidya, Varun; Partha, Gautam; Karmakar, Monita (2011-11-14). "Gender Differences in Utilization of Preventive Care Services in the United States". Journal of Women's Health. 21 (2): 140–145. doi:10.1089/jwh.2011.2876. ISSN 1540-9996. PMID 22081983.

- Merzel C (2000). "Gender differences in health care access indicators in an urban, low-income community". American Journal of Public Health. 90 (6): 909–916. doi:10.2105/ajph.90.6.909. PMC 1446268. PMID 10846508.

- Hoffmann, Diane E.; Tarzian, Anita J. (2001-03-01). "The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias against Women in the Treatment of Pain". The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 28 (4_suppl): 13–27. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2001.tb00037.x. ISSN 1073-1105.

- Liu, Katherine A.; Mager, Natalie A. Dipietro (2016). "Women's involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications". Pharmacy Practice. 14 (1): 708. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.708. ISSN 1885-642X. PMC 4800017. PMID 27011778.

- ORWH. "Including Women and Minorities in Clinical Research | ORWH". orwh.od.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- Mu, Ren; Zhang, Xiaobo (2011-01-01). "Why does the Great Chinese Famine affect the male and female survivors differently? Mortality selection versus son preference". Economics & Human Biology. 9 (1): 92–105. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2010.07.003. PMID 20732838.

- Anson O.; Sun S. (2002). "Gender and health in rural China: evidence from HeBei province". Social Science & Medicine. 55 (6): 1039–1054. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00227-1.

- Yu M.-Y.; Sarri R. (1997). "Women's health status and gender inequality in China". Social Science & Medicine. 45 (12): 1885–1898. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00127-5.

- Gupta, Monica Das (2005-09-01). "Explaining Asia's "Missing Women": A New Look at the Data". Population and Development Review. 31 (3): 529–535. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00082.x. ISSN 1728-4457.

- Behrman J. R. (1988). "Intrahousehold Allocation of Nutrients in Rural India: Are Boys Favored? Do Parents Exhibit Inequality Aversion?". Oxford Economic Papers. 40 (1): 32–54. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a041845.

- Asfaw A.; Lamanna F.; Klasen S. (2010). "Gender gap in parents' financing strategy for hospitalization of their children: evidence from India". Health Economics. 19 (3): 265–279. doi:10.1002/hec.1468. PMID 19267357.

- Uwer, Thomas von der Osten-Sacken ; Thomas (2007-01-01). "Is Female Genital Mutilation an Islamic Problem?". Middle East Quarterly.

- "Female genital mutilation (FGM)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- "Immediate health consequences of female genital mutilation | Reproductive Health Matters: reproductive & sexual health and rights". Reproductive Health Matters: reproductive & sexual health and rights. 2015-03-01. Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- "Gynecological consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C)". Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten. Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- Berg, Rigmor; Underland, Vigdis (June 10, 2013). "The Obstetric Consequences of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2013: 496564. doi:10.1155/2013/496564. PMC 3710629. PMID 23878544.

- Behrendt, Alice; Moritz, Steffen (2005-05-01). "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Memory Problems After Female Genital Mutilation". American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (5): 1000–1002. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.1000. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 15863806.

- Morison, Linda; Scherf, Caroline; Ekpo, Gloria; Paine, Katie; West, Beryl; Coleman, Rosalind; Walraven, Gijs (2001-08-01). "The long-term reproductive health consequences of female genital cutting in rural Gambia: a community-based survey". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 6 (8): 643–653. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.569.744. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00749.x. ISSN 1365-3156.

- Gee, GC; Payne-Sturges D. (2004). "Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environmental Health Perspectives". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (17): 1645–1653. doi:10.1289/ehp.7074. PMC 1253653. PMID 15579407.

- Woolf, S. H.; Braveman, P. (5 October 2011). "Where Health Disparities Begin: The Role Of Social And Economic Determinants--And Why Current Policies May Make Matters Worse". Health Affairs. 30 (10): 1852–1859. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0685. PMID 21976326.

- Andersen, RM (2007). Challenging the US Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 45–50.

- Miranda, Marie Lynn; Messer, Lynne C.; Kroeger, Gretchen L. (2 December 2011). "Associations Between the Quality of the Residential Built Environment and Pregnancy Outcomes Among Women in North Carolina". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (3): 471–477. doi:10.1289/ehp.1103578. PMC 3295337. PMID 22138639.

- Williams, David R.; Chiquita Collins (1995). "US Socioeconomic and Racial Differences in Health". Annual Review of Sociology. 21 (1): 349–386. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.21.1.349.

- Williams, D. R.; Jackson, P. B. (1 March 2005). "Social Sources Of Racial Disparities In Health". Health Affairs. 24 (2): 325–334. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. PMID 15757915.

- Williams, D. R. (2005). "Social Sources Of Racial Disparities In Health". Health Affairs. 24 (2): 325–334. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. PMID 15757915.

- Williams, DR; Collins C. (2001). "Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health". Public Health Reports. 116 (5): 404–416. doi:10.1093/phr/116.5.404. PMC 1497358. PMID 12042604.

- Mujahid MS; et al. (2011). "Neighborhood stressors and race/ethnic differences in hypertension prevalence". American Journal of Hypertension. 24 (2): 187–193. doi:10.1038/ajh.2010.200. PMC 3319083. PMID 20847728.

- Gee, GC; Payne-Sturges D (2004). "Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (17): 1645–1653. doi:10.1289/ehp.7074. PMC 1253653. PMID 15579407.

- "Field-Based Outreach Workers Facilitate Access to Health Care and Social Services for Underserved Individuals in Rural Areas". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2013-05-01. Retrieved 2013-05-13.

- Tikkanen, Roosa Sofia; Woolhandler, Steffie; Himmelstein, David U.; Kressin, Nancy R.; Hanchate, Amresh; Lin, Meng-Yun; McCormick, Danny; Lasser, Karen E. (2 February 2017). "Hospital Payer and Racial/Ethnic Mix at Private Academic Medical Centers in Boston and New York City". International Journal of Health Services. 47 (3): 460–476. doi:10.1177/0020731416689549. PMC 6090544. PMID 28152644.

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (KCMU), "The Uninsured and Their Access to Health Care" (December 2003).

- Fryer G. E.; Dovey S. M.; Green L. A. (2000). "The Importance of Having a Usual Source of Health Care". American Family Physician. 62: 477.

- Commonwealth Fund (CMWF), "Analysis of Minority Health Reveals Persistent, Widespread Disparities," press release (May 14, 1999).

- Goldberg, J., Hayes, W., and Huntley, J. "Understanding Health Disparities." Health Policy Institute of Ohio (November 2004), page 10.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), "National Healthcare Disparities Report," U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (July 2003).

- K. Collins, D. Hughes, M. Doty, B. Ives, J. Edwards, and K. Tenney, "Diverse Communities, Common Concerns: Assessing Health Care Quality for Minority Americans," Commonwealth Fund (March 2002).

- National Health Law Program and the Access Project (NHeLP), Language Services Action Kit: Interpreter Services in Health Care Settings for People With Limited English Proficiency (February 2004).

- Mluleki Tsawe, Appunni Sathiya Susuman (2014). "Determinants of access to and use of maternal health care services in the Eastern Cape, South Africa- a quantitative and qualitative investigation". BMC Research Notes. 7: 723. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-723. PMC 4203863. PMID 25315012.

- Goldberg, J., Hayes, W., and Huntley, J. "Understanding Health Disparities." Health Policy Institute of Ohio (November 2004), page 13.

- Brodie M, Flournoy RE, Altman DE, et al. (2000). "Health information, the Internet, and the digital divide". Health Affairs. 19 (6): 255–65. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.19.6.255. PMID 11192412.

- "Health Care Quality Survey". The Commonwealth Fund 2001.

- Betancourt, J. R. (2002). Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine.

- Ku, L.; Flores, G. (Mar–Apr 2005). "Pay Now or Pay Later: Providing Interpreter Services in Health Care". Health Affairs. 24 (2): 435–444. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.435. PMID 15757928.

- Floyd, Annette; Sakellariou, Dikaios (10 November 2017). "Healthcare access for refugee women with limited literacy: layers of disadvantage". International Journal for Equity in Health. 16 (1). doi:10.1186/s12939-017-0694-8. ISSN 1475-9276.

- Ng, Edward; Pottie, Kevin; Spitzer, Denise (December 2011). "Official language proficiency and self-reported health among immigrants to Canada" (PDF). Health Reports. 22 (4): 15–23.

- Fernandez; et al. (Feb 2004). "Physician Language Ability and Cultural Competence". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 19 (2): 167–174. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30266.x. PMC 1492135. PMID 15009796.

- Flores; et al. (Jan 2003). "Errors in Medical Interpretation and their Potential Clinical Consequences in Pediatric Encounters". Pediatrics. 111 (1): 6–14. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.488.9277. doi:10.1542/peds.111.1.6. PMID 12509547.

- Hamers; McNulty (Nov 2002). "Professional Interpreters and Bilingual Physicians in a Pediatric Emergency Department". Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 156 (11): 1108–1113. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.11.1108.

- Kleinman, A.; Eisenberg, L.; et al. (1978). "Culture, Illness and Care: Clinical Lessons for Anthropologic and Cross Culture Research". Annals of Internal Medicine. 88 (2): 251–258. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251.

- Goldberg, J., Hayes, W., and Huntley, J. "Understanding Health Disparities." Health Policy Institute of Ohio (November 2004), page 14.

- Handbook of health behavior research, David S. Gochman