Tropical disease

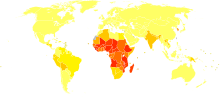

Tropical diseases are diseases that are prevalent in or unique to tropical and subtropical regions.[1] The diseases are less prevalent in temperate climates, due in part to the occurrence of a cold season, which controls the insect population by forcing hibernation. However, many were present in northern Europe and northern America in the 17th and 18th centuries before modern understanding of disease causation. The initial impetus for tropical medicine was to protect the health of colonial settlers, notably in India under the British Raj.[2] Insects such as mosquitoes and flies are by far the most common disease carrier, or vector. These insects may carry a parasite, bacterium or virus that is infectious to humans and animals. Most often disease is transmitted by an insect "bite", which causes transmission of the infectious agent through subcutaneous blood exchange. Vaccines are not available for most of the diseases listed here, and many do not have cures.

Human exploration of tropical rainforests, deforestation, rising immigration and increased international air travel and other tourism to tropical regions has led to an increased incidence of such diseases to non-tropical countries.[3][4]

Health programmes

In 1975 the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) was established to focus on neglected infectious diseases which disproportionately affect poor and marginalized populations in developing regions of Africa, Asia, Central America and South America. It was established at the World Health Organization, which is the executing agency, and is co-sponsored by the United Nations Children's Fund, United Nations Development Programme, the World Bank and the World Health Organization.

TDR's vision is to foster an effective global research effort on infectious diseases of poverty in which disease endemic countries play a pivotal role. It has a dual mission of developing new tools and strategies against these diseases, and to develop the research and leadership capacity in the countries where the diseases occur. The TDR secretariat is based in Geneva, Switzerland, but the work is conducted throughout the world through many partners and funded grants.

Some examples of work include helping to develop new treatments for diseases, such as ivermectin for onchocerciasis (river blindness); showing how packaging can improve use of artemesinin-combination treatment (ACT) for malaria; demonstrating the effectiveness of bednets to prevent mosquito bites and malaria; and documenting how community-based and community-led programmes increases distribution of multiple treatments. TDR history

The current TDR disease portfolio includes the following entries:[5]

- Chagas disease

- (also called American trypanosomiasis) is a parasitic disease which occurs in the Americas, particularly in South America. Its pathogenic agent is a flagellate protozoan named Trypanosoma cruzi, which is transmitted mostly by blood-sucking assassin bugs, however other methods of transmission are possible, such as ingestion of food contaminated with parasites, blood transfusion and fetal transmission. Between 16 and 18 million people are currently infected.[6]

- Dengue

- Helminths

- African trypanosomiasis

- Leishmaniasis

- Leprosy†

- (or Hansen's disease) is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae. Leprosy is primarily a granulomatous disease of the peripheral nerves and mucosa of the upper respiratory tract; skin lesions are the primary external symptom.[7] Left untreated, leprosy can be progressive, causing permanent damage to the skin, nerves, limbs, and eyes. Contrary to popular conception, leprosy does not cause body parts to simply fall off, and it differs from tzaraath, the malady described in the Hebrew scriptures and previously translated into English as leprosy.[8]

- Lymphatic filariasis

- is a parasitic disease caused by thread-like parasitic filarial worms called nematodes, all transmitted by mosquitoes. Loa loa is another filarial parasite transmitted by the deer fly. 120 million people are infected worldwide. It is carried by over half the population in the most severe endemic areas.[9] The most noticeable symptom is elephantiasis: a thickening of the skin and underlying tissues. Elephantiasis is caused by chronic infection by filarial worms in the lymph nodes. This clogs the lymph nodes and slows the draining of lymph fluid from a portion of the body.

- Malaria

- Onchocerciasis (/ˌɒŋkoʊsɜːrˈkaɪəsɪs, -ˈsaɪ-/[11][12])

- or river blindness is the world's second leading infectious cause of blindness. It is caused by Onchocerca volvulus, a parasitic worm.[13] It is transmitted through the bite of a black fly. The worms spread throughout the body, and when they die, they cause intense itching and a strong immune system response that can destroy nearby tissue, such as the eye.[14] About 18 million people are currently infected with this parasite. Approximately 300,000 have been irreversibly blinded by it.[15]

- Schistosomiasis (/ˌʃɪstəsəˈmaɪəsɪs/[16][17])

- also known as schisto or snail fever, is a parasitic disease caused by several species of flatworm in areas with freshwater snails, which may carry the parasite. The most common form of transmission is by wading or swimming in lakes, ponds and other bodies of water containing the snails and the parasite. More than 200 million people worldwide are infected by schistosomiasis.[18]

- Sexually transmitted infections

- TB-HIV coinfection

- Tuberculosis†

- (abbreviated as TB), is a bacterial infection of the lungs or other tissues, which is highly prevalent in the world, with mortality over 50% if untreated. It is a communicable disease, transmitted by aerosol expectorant from a cough, sneeze, speak, kiss, or spit. Over one-third of the world's population has been infected by the TB bacterium.[19]

- † Although leprosy and tuberculosis are not exclusively tropical diseases, their high incidence in the tropics justifies their inclusion.

Other neglected tropical diseases

Additional neglected tropical diseases include:[20]

| Disease | Causative Agent | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Hookworm | Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus | |

| Trichuriasis | Trichuris trichiura | |

| Treponematoses | Treponema pallidum pertenue, Treponema pallidum endemicum, Treponema pallidum carateum, Treponema pallidum pallidum | |

| Buruli ulcer | Mycobacterium ulcerans | |

| Human African trypanosomiasis | Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma gambiense | |

| Dracunculiasis | Dracunculus medinensis | |

| Leptospirosis | Leptospira | |

| Strongyloidiasis | Strongyloides stercoralis | |

| Foodborne trematodiases | Trematoda | |

| Neurocysticercosis | Taenia solium | |

| Scabies | Sarcoptes scabiei | |

| Flavivirus Infections | Yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, dengue virus, Tick-borne encephalitis virus, Zika virus |

Some tropical diseases are very rare, but may occur in sudden epidemics, such as the Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Lassa fever and the Marburg virus. There are hundreds of different tropical diseases which are less known or rarer, but that, nonetheless, have importance for public health.

Relation of climate to tropical diseases

The so-called "exotic" diseases in the tropics have long been noted both by travelers, explorers, etc., as well as by physicians. One obvious reason is that the hot climate present during all the year and the larger volume of rains directly affect the formation of breeding grounds, the larger number and variety of natural reservoirs and animal diseases that can be transmitted to humans (zoonosis), the largest number of possible insect vectors of diseases. It is possible also that higher temperatures may favor the replication of pathogenic agents both inside and outside biological organisms. Socio-economic factors may be also in operation, since most of the poorest nations of the world are in the tropics. Tropical countries like Brazil, which have improved their socio-economic situation and invested in hygiene, public health and the combat of transmissible diseases have achieved dramatic results in relation to the elimination or decrease of many endemic tropical diseases in their territory.

Climate change, global warming caused by the greenhouse effect, and the resulting increase in global temperatures, are possibly causing tropical diseases and vectors to spread to higher altitudes in mountainous regions, and to higher latitudes that were previously spared, such as the Southern United States, the Mediterranean area, etc.[21][22] For example, in the Monteverde cloud forest of Costa Rica, global warming enabled Chytridiomycosis, a tropical disease, to flourish and thus force into decline amphibian populations of the Monteverde Harlequin frog.[23] Here, global warming raised the heights of orographic cloud formation, and thus produced cloud cover that would facilitate optimum growth conditions for the implicated pathogen, B. dendrobatidis.

Prevention and treatment of tropical diseases

Some of the strategies for controlling tropical diseases include:

- Draining wetlands to reduce populations of insects and other vectors, or introducing natural predators of the vectors.

- The application of insecticides and/or insect repellents) to strategic surfaces such as clothing, skin, buildings, insect habitats, and bed nets.

- The use of a mosquito net over a bed (also known as a "bed net") to reduce nighttime transmission, since certain species of tropical mosquitoes feed mainly at night.

- Use of water wells, and/or water filtration, water filters, or water treatment with water tablets to produce drinking water free of parasites.

- Sanitation to prevent transmission through human waste.

- In situations where vectors (such as mosquitoes) have become more numerous as a result of human activity, a careful investigation can provide clues: for example, open dumps can contain stagnant water that encourage disease vectors to breed. Eliminating these dumps can address the problem. An education campaign can yield significant benefits at low cost.

- Development and use of vaccines to promote disease immunity.

- Pharmacologic pre-exposure prophylaxis (to prevent disease before exposure to the environment and/or vector).

- Pharmacologic post-exposure prophylaxis (to prevent disease after exposure to the environment and/or vector).

- Pharmacologic treatment (to treat disease after infection or infestation).

- Assisting with economic development in endemic regions. For example, by providing microloans to enable investments in more efficient and productive agriculture. This in turn can help subsistence farming to become more profitable, and these profits can be used by local populations for disease prevention and treatment, with the added benefit of reducing the poverty rate.

See also

- Hospital for Tropical Diseases

- Tropical medicine

- Infectious disease

- Neglected diseases

- List of epidemics

- Waterborne diseases

- Globalization and disease

References

- Farrar, Jeremy; Hotez, Peter J; Junghanss, Thomas; Kang, Gagandeep; Lalloo, David; White, Nicholas (2013). Manson's tropical diseases (New ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders [Imprint]. ISBN 9780702051012.

- Farley, John (2003). Bilharzia : a history of imperial tropical medicine (1. paperback ed.). [S.l.]: Cambridge Univ Press. ISBN 0521530601.

- "Deforestation Boosts Malaria Rates, Study Finds". npr.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- UK 'faces tropical disease threat' Archived 2006-06-15 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News

- "Disease portfolio". Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. Archived from the original on 2008-01-13. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- "Chagas Disease After Organ Transplantation --- United States, 2001". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Kenneth J. Ryan and C. George Ray, Sherris Medical Microbiology Fourth Edition McGraw Hill 2004.

- Leviticus 13:59, Artscroll Tanakh and Metsudah Chumash translations, 1996 and 1994, respectively.

- Supali, T.; Ismid, I.S.; Wibowo, H.; Djuardi, Y.; Majawati, E.; Ginanjar, P.; Fischer, P. (Aug 2006). "Estimation of the prevalence of lymphatic filariasis by a pool screen PCR assay using blood spots collected on filter paper". Tran R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 100 (8): 753–9. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.10.005. ISSN 0035-9203. PMID 16442578.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2017-09-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Onchocerciasis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Onchocerciasis". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-03-24. Retrieved 2008-03-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The World Bank | Global Partnership to Eliminate Riverblindness. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- "Causes of river blindness". Archived from the original on 2007-12-29. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- "What is river blindness?". Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- "Schistosomiasis". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Schistosomiasis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Schistosomiasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104 - Global and regional incidence. Archived 2006-10-04 at the Wayback Machine March 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- Hotez, P. J.; Molyneux, DH; Fenwick, A; Kumaresan, J; Sachs, SE; Sachs, JD; Savioli, L (September 2007). "Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (10): 1018–1027. doi:10.1056/NEJMra064142. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 17804846. 17804846. Archived from the original on 2008-01-02. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- Climate change brings malaria back to Italy Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian 6 January 2007

- BBC Climate link to African malaria Archived 2006-06-16 at the Wayback Machine 20 March 2006.

- Pounds, J. Alan et al. "Widespread Amphibian Extinctions from Epidemic Deisease Driven by Global Warming." Nature 439.12 (2006) 161-67

Further reading

Books

- TDR at a glance - fostering an effective global research effort on diseases of poverty

- Le TDR en un coup d’oeilLe TDR en un coup d’oeil - favoriser un eff ort mondial de recherche eff icace sur les maladies liées à la pauvreté

- TDR annual report - 2009

- Monitoring and evaluation tool kit for indoor residual spraying

- Indicators for monitoring and evaluation of the kala-azar elimination programme

- Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test Performance - results of WHO product testing of malaria RDTs: Round 2- 2009

- Quality Practices in Basic Biomedical Research (QPBR) training manual: Trainer

- Quality Practices in Basic Biomedical Research (QPBR) training manual: Trainee

- Progress and prospects for the use of genetically modified mosquitoes to inhibit disease transmission

- Use of Influenza Rapid Diagnostic Tests

- Manson's Tropical Diseases

- Mandell's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases or this site

Journals

- American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

- Japanese Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

- Tropical Medicine and International Health

- The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health

- Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo

- Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical

- Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tropical diseases. |

- WHO Neglected Tropical Diseases

- WHO Operational research in tropical and other communicable diseases

- European Bioinformatics Institute

- open source drug discovery

- Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative

- Tropical diseases from Maya Paradise, The Guatemala Information Web Site

- American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

- Treating Tropical Diseases U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Travelers' Health - National Center for Infectious Diseases - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Professor Andrew Speilman, Harvard School of Tropical Medicine Freeview Malaria video by the Vega Science Trust.

- Rob Hutchingson, Entomolgoist, London School of Tropical Medicine, Mosquitoes Freeview 'Snapshot' video by the Vega Science Trust.

- Links to pictures of tropical diseases (Hardin MD/Univ of Iowa)

- Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine - New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

- Tropical Diseases Web Ring

- Tropicology Library. In Portuguese.

- Institute for Tropical Medicine - Antwerp - Belgium

- Lecture Notes ITM - Antwerp - Belgium

- Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University - Bangkok - Thailand

- 'Conquest and Disease or Colonisation and Health', lecture by Professor Frank Cox on the history of tropical disease, given at Gresham College, 17 September 2007 (available for download as video and audio files, as well as a text file).

- NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (2007, December 28). "Neglected Tropical Diseases Burden Those Overseas, But Travelers Also At Risk". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- Colombian Institute of Tropical Medicine ICMT-CES University