Dandruff

Dandruff is a skin condition that mainly affects the scalp. Symptoms include flaking and sometimes mild itchiness. It can result in social or self-esteem problems.[1] A more severe form of the condition, which includes inflammation of the skin, is known as seborrhoeic dermatitis.

| Dandruff | |

|---|---|

| |

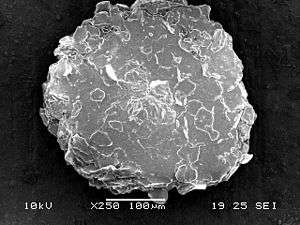

| A microscopic image of human dandruff | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Itchy and flaking skin of the scalp |

| Usual onset | Puberty |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms |

| Differential diagnosis | Psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, tinea capitis, rosacea, systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Medication | Antifungal cream (ketoconazole) |

| Frequency | ~50% of adults |

The cause is unclear, but believed to involve a number of genetic and environmental factors. The condition may worsen in the winter.[2] It is not due to poor hygiene.[3] The underlying mechanism involves the excessive growth of skin cells.[2] Diagnosis is based on symptoms.

There is no known cure for dandruff.[4] Antifungal cream, such as ketoconazole, may be used to try to improve the condition. Dandruff affects about half of adults, with males more often affected than females. Onset is usually at puberty, with rates decreasing after the age of 50.

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of dandruff are an itchy scalp and flakiness.[5] Red and greasy patches of skin and a tingly feeling on the skin are also symptoms.[6]

Causes

The cause is unclear but believed to involve a number of genetic and environmental factors. The condition may worsen in the winter.[2] It is not due to poor hygiene.[3]

As the skin layers continually replace themselves, cells are pushed outward where they die and flake off. For most individuals, these flakes of skin are too small to be visible. However, certain conditions cause cell turnover to be unusually rapid, especially in the scalp. It is hypothesized that for people with dandruff, skin cells may mature and be shed in 2–7 days, as opposed to around a month in people without dandruff. The result is that dead skin cells are shed in large, oily clumps, which appear as white or grayish flakes on the scalp, skin and clothes.

According to one study, dandruff has been shown to be possibly the result of three factors:[7]

- Skin oil commonly referred to as sebum or sebaceous secretions[8]

- The metabolic by-products of skin micro-organisms (most specifically Malassezia yeasts)[9][10][11][12][13]

- Individual susceptibility and allergy sensitivity.

Microorganisms

According to a 2016 study, bacteria (mainly Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus) are more important to dandruff formation than fungi. Bacterial presence was in turn influenced by water and sebum amount.[14]

Older literature cites the fungus Malassezia furfur (previously known as Pityrosporum ovale) as the cause of dandruff. While this species does occur naturally on the skin surface of people both with and without dandruff, in 2007 it was discovered that the responsible agent is a scalp specific fungus, Malassezia globosa,[15] that metabolizes triglycerides present in sebum by the expression of lipase, resulting in a lipid byproduct oleic acid. During dandruff, the levels of Malassezia increase by 1.5 to 2 times its normal level.[2] Oleic acid penetrates the top layer of the epidermis, the stratum corneum, and evokes an inflammatory response in susceptible people which disturbs homeostasis and results in erratic cleavage of stratum corneum cells.[11]

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

In seborrhoeic dermatitis, redness and itching frequently occur around the folds of the nose and eyebrow areas, not just the scalp. Dry, thick, well-defined lesions consisting of large, silvery scales may be traced to the less common condition of scalp psoriasis. Inflammation can be characterized by redness, heat, pain, swelling and can cause sensitivity.

Inflammation and extension of scaling outside the scalp exclude the diagnosis of dandruff from seborrhoeic dermatitis.[8] However, many reports suggest a clear link between the two clinical entities - the mildest form of the clinical presentation of seborrhoeic dermatitis as dandruff, where the inflammation is minimal and remain subclinical.[16][17]

Seasonal changes, stress, and immunosuppression seem to affect seborrheic dermatitis.[2]

Mechanism

Dandruff scale is a cluster of corneocytes, which have retained a large degree of cohesion with one another and detach as such from the surface of the stratum corneum. A corneocyte is a protein complex that is made of tiny threads of keratin in an organised matrix.[18] The size and abundance of scales are heterogeneous from one site to another and over time. Parakeratotic cells often make up part of dandruff. Their numbers are related to the severity of the clinical manifestations, which may also be influenced by seborrhea.[2]

Treatment

Shampoos use a combination of special ingredients to control dandruff.

Antifungals

Antifungal treatments including ketoconazole, zinc pyrithione and selenium disulfide have been found to be effective.[5] Ketoconazole appears to have a longer duration of effect.[5] Ketoconazole is a broad spectrum antimycotic agent that is active against Candida and M. furfur. Of all the antifungals of the imidazole class, ketoconazole has become the leading contender among treatment options because of its effectiveness in treating seborrheic dermatitis as well.[2]

Ciclopirox is widely used as an anti-dandruff agent in most preparations.[19]

Epidemiology

Dandruff affects around half of all adults.[5]

Etymology

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word dandruff is first attested in 1545, but is still of unknown etymology.[21]

References

- Grimalt, R. (December 2007). "A Practical Guide to Scalp Disorders". Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings. 12 (2): 10–14. doi:10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650048. PMID 18004290.

- Ranganathan, S; Mukhopadhyay, T (2010). "Dandruff: the most commercially exploited skin disease". Indian Journal of Dermatology. 55 (2): 130–4. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.62734. PMC 2887514. PMID 20606879.

- "Dandruff: How to treat". American Academy of Dermatology. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Turkington, Carol; Dover, Jeffrey S. (2007). The Encyclopedia of Skin and Skin Disorders (Third ed.). Facts On File, Inc. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-8160-6403-8. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016.

- Turner, GA; Hoptroff, M; Harding, CR (August 2012). "Stratum corneum dysfunction in dandruff". International Journal of Cosmetic Science. 34 (4): 298–306. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2494.2012.00723.x. PMC 3494381. PMID 22515370.

- "What Is Dandruff? Learn All About Dandruff". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015.

- DeAngelis YM, Gemmer CM, Kaczvinsky JR, Kenneally DC, Schwartz JR, Dawson TL (2005). "Three etiologic facets of dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis: Malassezia fungi, sebaceous lipids, and individual sensitivity". J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 10 (3): 295–7. doi:10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10119.x. PMID 16382685.

- Ro BI, Dawson TL (2005). "The role of sebaceous gland activity and scalp microfloral metabolism in the etiology of seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff". J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 10 (3): 194–7. doi:10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10104.x. PMID 16382662.

- Ashbee HR, Evans EG (2002). "Immunology of Diseases Associated with Malassezia Species". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15 (1): 21–57. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.1.21-57.2002. PMC 118058. PMID 11781265.

- Batra R, Boekhout T, Guého E, Cabañes FJ, Dawson TL, Gupta AK (2005). "Malassezia Baillon, emerging clinical yeasts". FEMS Yeast Res. 5 (12): 1101–13. doi:10.1016/j.femsyr.2005.05.006. PMID 16084129.

- Dawson TL (2006). "Malassezia and seborrheic dermatitis: etiology and treatment". Journal of Cosmetic Science. 57 (2): 181–2. PMID 16758556.

- Gemmer CM, DeAngelis YM, Theelen B, Boekhout T, Dawson Jr TL (2002). "Fast, Noninvasive Method for Molecular Detection and Differentiation of Malassezia Yeast Species on Human Skin and Application of the Method to Dandruff Microbiology". J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 (9): 3350–7. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.9.3350-3357.2002. PMC 130704. PMID 12202578.

- Gupta AK, Batra R, Bluhm R, Boekhout T, Dawson TL (2004). "Skin diseases associated with Malassezia species". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 51 (5): 785–98. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.12.034. PMID 15523360.

- Xu, Zhijue; Wang, Zongxiu; Yuan, Chao; Liu, Xiaoping; Yang, Fang; Wang, Ting; Wang, Junling; Manabe, Kenji; Qin, Ou; Wang, Xuemin; Zhang, Yan; Zhang, Menghui (2016). "Dandruff is associated with the conjoined interactions between host and microorganisms". Scientific Reports. 6: 24877. doi:10.1038/srep24877. PMC 4864613. PMID 27172459.

- "Genetic code of dandruff cracked". BBC News. 6 November 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Pierard-Franchimont C, Hermanns JF, Degreef H, Pierard GE (2006). "Revisiting dandruff". Int J Cosmet Sci. 28 (5): 311–318. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2494.2006.00326.x. PMID 18489295.

- Pierard-Franchimont C, Hermanns JF, Degreef H, Pierard GE. From axioms to new insights into dandruff. Dermatology 2000;200:93-8.

- Brannon, Heather. "The Structure and Function of the Stratum Corneum". Dermatology.about.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Milani, M; Antonio Di Molfetta, S; Gramazio, R; Fiorella, C; Frisario, C; Fuzio, E; Marzocca, V; Zurilli, M; Di Turi, G; Felice, G (2003). "Efficacy of betamethasone valerate 0.1% thermophobic foam in seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp: An open-label, multicentre, prospective trial on 180 patients". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 19 (4): 342–5. doi:10.1185/030079903125001875. PMID 12841928.

- GENERIC NAME(S): Coal TarFind Lowest Prices (16 August 2017). "Anti-Dandruff (coal tar)". WebMD. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- "dandruff | dandriff, n." OED Online. Oxford University Press, March 2015. Web. Retrieved 27 April 2015.