Chronic wasting disease

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) affecting cervids, the deer family. TSEs are a family of diseases thought to be caused by misfolded proteins called prions and includes similar diseases such as BSE (mad cow disease) in cattle, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans and scrapie in sheep.[1] In the US, CWD affects mule deer, white-tailed deer, red deer, sika deer, elk (or "wapiti"), moose, caribou, and reindeer.[2] Natural infection causing CWD affects members of the deer family.[2] Experimental transmission of CWD to other species such as squirrel monkeys, and genetically modified mice has been shown.[3] In 1967, CWD was first identified in mule deer at a government research facility in northern Colorado, United States.[2] It was initially recognized as a clinical "wasting" syndrome and then in 1978, it was identified more specifically as a TSE disease. Since then, CWD has been found in free-ranging and captive animal populations in 26 US states and three Canadian provinces.[4] In addition, CWD has been found in one Minnesota red deer farm, one wild reindeer herd in Norway (March 2016) as well as in wild moose. Single cases of CWD in moose have been found in Finland (March 2018) and in Sweden (March and May 2019). CWD was found in South Korea in some deer imported from Canada.[5] CWD is typified by chronic weight and clinical signs compatible with brain lesions, aggravated over time, always leading to death. No relationship is known between CWD and any other TSEs of animals or people.

| Chronic wasting disease | |

|---|---|

| |

| This deer visibly shows signs of chronic wasting disease. | |

| Specialty | Veterinary medicine |

Although reports in the popular press have been made of humans being affected by CWD, by 2004 a study for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested, "[m]ore epidemiologic and laboratory studies are needed to monitor the possibility of such transmissions".[6]

The epidemiological study further concluded, "[a]s a precaution, hunters should avoid eating deer and elk tissues known to harbor the CWD agent (e.g., brain, spinal cord, eyes, spleen, tonsils, lymph nodes) from areas where CWD has been identified".[6]

Signs and symptoms

Most cases of CWD occur in adult animals; the youngest animal to exhibit clinical symptoms of the disease was 15 months.[7] The disease is progressive and always fatal. The first signs are difficulties in movement. The most obvious and consistent clinical sign of CWD is weight loss over time. Behavioral changes also occur in the majority of cases, including decreased interactions with other animals, listlessness, lowering of the head, tremors, repetitive walking in set patterns, and nervousness. Excessive salivation and grinding of the teeth also are observed. Most deer show increased drinking and urination; the increased drinking and salivation may contribute to the spread of the disease.[8] Loss of fear of humans and appearance of confusion are also common.[9] A scientist at APHIS summed it up this way:[2]

| “ | Behavioral changes, emaciation, weakness, ataxia, salivation, aspiration pneumonia, progressive death. | ” |

Cause

The cause of CWD (like other TSEs, such as scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy) is believed to be a prion, a misfolded form of a normal protein, known as prion protein (PrP), that is most commonly found in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). The misfolded form has been shown to be capable of converting normally folded prion protein, PrPC ("C" for cellular) into an abnormal form, PrPSc ("Sc" for scrapie), thus leading to a chain reaction. CWD is thought to be transmitted by this mechanism. The abnormality in PrP has its genetic basis in a particular variant of the protein-coding gene PRNP that is highly conserved among mammals and has been found and sequenced in deer. The build-up of PrPd in the brain is associated with widespread neurodegeneration.[2][8][10] However, the prion cannot be detected in about 10% of CWD cases, leading some to suspect something else causes the diseases and that the prion is just a marker of infection.

A dual eco-prerequisite theory is proposed on the aetiology of TSEs which is based upon an Ag, Ba, Sr or Mn replacement binding at the vacant Cu/Zn domains on the cellular prion protein (PrP)/sulphated proteoglycan molecules which impairs the capacities of the brain to protect itself against incoming shockbursts of sound and light energy. The elevated levels of these metals in the environment -- Ag, Ba and Sr -- were thought to originate from both natural geochemical and artificial pollutant sources--stemming from the common practise of aerial spraying with 'cloud seeding' Ag or Ba crystal nuclei for rain making in these drought prone areas of North America, the atmospheric spraying with Ba based aerosols for enhancing/refracting radar and radio signal communications as well as the spreading of waste Ba drilling mud from the local oil/gas well industry across pastureland. These metals have subsequently bioconcentrated up the foodchain and into the mammals who are dependent upon the local Cu deficient ecosystems[11].

Another theory that has gained some support since 2017 is that the cause is a cell wall-deficient bacterium called Spiroplasma. Frank Bastian of Louisiana State University has long been unsuccessfully trying to grow Spiroplasma from the brains of infected animals, where it would grow for about 10 hours, then die. Bastian claims to have successfully cultured Spiroplasma from the brains of 100% of deer with CWD and sheep with scrapie after changing the growth medium. As a result, a Pennsylvania hunting agency, Unified Sportsmen of Pennsylvania, and scientists at the University of Alabama have taken interest in his work. Spiroplasma possesses many of the properties of the CWD agent, including resistance to heat and radiation, and it is thought that the body may trigger prion formation as a defense mechanism against Spiroplasma. The prion may also protect Spiroplasma from attack by the adaptive immune system.[12][13][14]

Genetics

The allele which encodes leucine, codon 132 in the family of Elks, is either homozygous LL, homozygous MM, or heterozygous ML. Individuals with the first encoding seem to resist clinical signs of CWD, whereas individuals with either of the other two encodings have much shorter incubation periods.[2]

Codon 96 polymorphisms in the white-tailed deer family cause delay in clinical onset and disease progression.[2][15]

Spread

As of 2013, no evidence has been found of transmission to humans from cervids, nor by eating cervids, but both channels remain a subject of public health surveillance and research.[2] Dr Neil Cashman, an academic at the UBC who specialises in prions and is CSO of Amorfix said in July 2019 that "with all the research on the malignity of prions, and the permanence of prions in the wider environment, and their resistance to destruction and degradation, it is necessary to reduce the potential sources of exposure to CWD."[16] In fact an APHIS scientist observed that, while the longevity of CWD prion is unknown, the scrapie prion has been measured to endure for 16 years.[2][17] The PrPCWD protein is insoluble in all but the strongest solvents, and highly resistant to digestion by proteases.[2] PrPCWD converts the normal protein PrPC into more of itself upon contact, and binds together forming aggregates.[2][17] Prusiner noted in 2001 that[17]

| “ | In the prion diseases, the initial formation of PrPSc leads to an exponential increase in the protein, which can be readily transmitted to another host | ” |

but it is noted that as of 2013, although CWD prions were transmissible within the cervidae family, CWD was not transmissible to humans or to cattle.[2]

Direct

CWD may be directly transmitted by contact with infected animals, their bodily tissues, and their bodily fluids.[18] Transmission may result from contact with both clinically affected and infected, but asymptomatic, cervids.[19]

Recent research on Rocky Mountain elk found that with CWD-infected dams, many subclinical, a high rate (80%) of maternal-to-offspring transmission of CWD prions occurred, regardless of gestational period.[19] While not dispositive relative to disease development in the fetus, this does suggest that maternal transmission may be yet another important route of direct CWD transmission.

Experimental transmission

In addition to the cervid species in which CWD is known to naturally occur, black-tailed deer and European red deer have been demonstrated to be naturally susceptible to CWD.[20] Other cervid species, including caribou, are also suspected to be naturally vulnerable to this disease.[18] Many other noncervid mammalian species have been experimentally infected with CWD, either orally or by intracerebral inoculation.[18] These species include monkeys, sheep, cattle, prairie voles, mice, and ferrets.[21]

An experimental case study of oral transmission of CWD to reindeer shows certain reindeer breeds may be susceptible to CWD, while other subpopulations may be protective against CWD in free-ranging populations. None of the reindeer in the study showed symptoms of CWD, potentially signifying resistance to different CWD strains.[22]

Indirect

Environmental transmission has been linked to contact with infected bodily fluids and tissues, as well as contact with contaminated environments. Once in the environment, CWD prions may remain infectious for many years. Thus, decomposition of diseased carcasses, infected "gut piles" from hunters who field dress their cervid harvests, and the urine, saliva, feces, and antler velvet of infected individuals that are deposited in the environment, all have the potential to create infectious environmental reservoirs of CWD.[8]

In 2013, researchers at the National Wildlife Research Center in Fort Collins, Colorado successfully inoculated white-tailed deer with the misfolded prion via the nasal passage, when the prions were immisced with clay.[23] This was important because the prions had already been shown by 2006 to bind with sandy quartz clay minerals.[2]

One avian scavenger, the American crow, was recently evaluated as a potential vector for CWD.[24] As CWD prions remain viable after passing through the bird's digestive tract, crows represent a possible mechanism for the creation of environmental reservoirs of CWD.[24][25] Additionally, the crows' extensive geographic range presents ample opportunities for them to come in contact with CWD. This, coupled with the population density and longevity of communal roosting sites in both urban and rural locations, suggests that the fecal deposits at roosting sites may represent a CWD environmental reservoir.[24] Conservative estimates for crows' fecal deposits at one winter roosting site for one winter season ranged from 391,552 to 599,032 kg.[24]

CWD prions adhere so tightly to soil surface particles that the ground becomes a source of infection and may be a major route of transmission due to frequent ground contact when cervids graze.[8]

Control and eradication efforts

By 2012, a voluntary system of control was published by APHIS in the US Federal Register. It depended on voluntary minimum standards methodology, and herd certification programs to avoid interstate movement of the disease vector. It was based on a risk management framework.[2] As of August 2019, APHIS law in 9 CFR Part 55 - CONTROL OF CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE dealt with this problem.

The MFFP ministry in Quebec practiced 9500 tests in the period between 2007 and autumn 2018 before they detected a seropositive case in September 2018.[26]

The September 2018 discovery of CWD on a managed operation in Grenville-sur-la-Rouge Quebec prompted a wholesale slaughter of 3500 animals in two months before the enterprise shut its doors for good.[27] The CFIA ordered the cull, as well as the decontamination of 10 inches of soil in certain places on the 1000-acre operation.[26] Post-discovery, each animal was tested for CWD by the CFIA before it was released onto the market. Other Quebec producers lamented the glut of supply.[27] A 400 km quarantine area was declared, in which all hunting and trapping activities were banned.[28] Government massacred hundreds of wild beasts over a two-month period. The routine cull for market was between 70 and 100 animals per week. When the producer was forced to close, the weekly slaughter neared 500 beasts per week.[27] One year later, 750 wild specimens had been culled in the 45 km-radius "enhanced monitoring area", and none tested positive for CWD.[29]

It came to light in August 2019 that prior to 2014 in Canada, all animals on CWD-infected farms were buried or incinerated. But in a mysterious change of policy, since then the CFIA has allowed animals from CWD-infected farms to enter the food chain because there is "no national requirement to have animals tested for the disease". From one CWD-infected herd in Alberta, 131 elk were sold for human consumption.[30]

For the fall 2019 hunting season in western Quebec, the provincial ministry relaxed the rules for the annual white-tailed deer (WTD) hunt, in an effort to curb the spread of CWD. Any WTD can be hunted with any weapon in certain municipalities in the Outaouais valley and the Laurentides. The MFFP hopes thereby to receive more samples to test for CWD.[29] The quarantine around Grenville was still in place, and the ministry specifically prohibited (only) the "removal" from the quarantine "enhanced monitoring area" zone of "the head, more specifically any part of the brain, the eyes, the retropharyngeal lymph nodes and the tonsils, any part of the spinal column, the internal organs (including the liver and the heart), and the testicles."[31]

Introduced for the 2019 Minnesota hunting season, a no-cost deer carcass-incineration program was rolled out by Crow Wing County officials hoping to stem the spread of CWD in the region. CWD was found among wild deer in Crow Wing County for the first time in January 2019. The voluntary program encourages both residents and visiting hunters to bring harvested deer carcasses to the county landfill east of Brainerd, Minnesota for incineration and disposal.[9]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on post mortem examination (necropsy) and testing; examination of the dead body is not definitive, as many animals die early in the course of the disease and conditions found are nonspecific; general signs of poor health and aspiration pneumonia, which may be the actual cause of death, are common. On microscopic examination, lesions of CWD in the CNS resemble those of other TSEs. In addition, scientists use immunohistochemistry to test brain, lymph, and neuroendocrine tissues for the presence of the abnormal prion protein to diagnose CWD; positive IHC findings in the obex is considered the gold standard.[8]

Available tests at the CFIA were not as of July 2019 sensitive enough to detect the prion in specimens less than a year old.[16]

As of 2015, no commercially feasible diagnostic tests could be used on live animals.[8] As early as 2001 an antemortem test was deemed urgent.[32] Running a bioassay, taking fluids from cervids suspected of infection and incubating them in transgenic mice that express the cervid prion protein, can be used to determine whether the cervid is infected, but ethical issues exist with this, and it is not scalable.[8]

A tonsillar biopsy technique has been a reliable method of testing for CWD in live deer,[33] but it only seems to be effective on mule deer and white-tailed deer, not elk.[34] Biopsies of the rectal mucosa have also been effective at detecting CWD in live mule deer, white-tailed deer, and elk, though detection efficacy may be influenced by numerous factors including animal age, genotype, and disease stage.[35][36][37][38]

Epidemiology

The origin and mode of transmission of the prions causing CWD is unknown, but recent research indicates that prions can be excreted by deer and elk, and are transmitted by eating grass growing in contaminated soil.[39][40] Animals born in captivity and those born in the wild have been affected with the disease. Based on epidemiology, transmission of CWD is thought to be lateral (from animal to animal). Maternal transmission may occur, although it appears to be relatively unimportant in maintaining epidemics. An infected deer's saliva is able to spread the CWD prions.[41] Exposure between animals is associated with sharing food and water sources contaminated with CWD prions shed by diseased deer.[42]

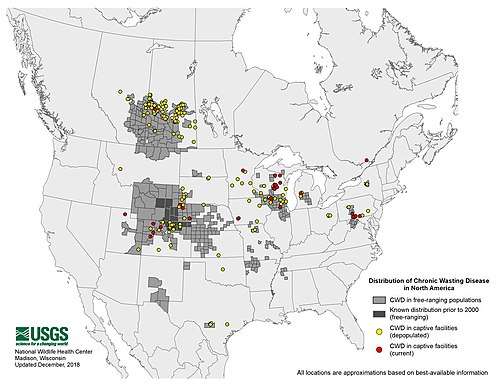

North America

The disease was first identified in 1967 in a closed herd of captive mule deer in contiguous portions of northeastern Colorado. In 1980, the disease was determined to be a TSE. It was first identified in wild elk and mule deer and white-tailed deer in the early 1980s in Colorado and Wyoming, and in farmed elk in 1997.[2][8][10] Canada was not affected by the disease until 1996.[16]

In May 2001, CWD was also found in free-ranging deer in the southwestern corner of Nebraska (adjacent to Colorado and Wyoming) and later in additional areas in western Nebraska. The limited area of northern Colorado, southern Wyoming, and western Nebraska in which free-ranging deer, moose, and/or elk positive for CWD have been found is referred to as the endemic area. The area in 2006 has expanded to six states, including parts of eastern Utah, southwestern South Dakota, and northwestern Kansas. Also, areas not contiguous (to the endemic area) areas in central Utah and central Nebraska have been found. The limits of the affected areas are not well defined, since the disease is at a low incidence and the amount of sampling may not be adequate to detect it. In 2002, CWD was detected in wild deer in south-central Wisconsin and northern Illinois and in an isolated area of southern New Mexico. In 2005, it was found in wild white-tailed deer in New York and in Hampshire County, West Virginia.[43] In 2008, the first confirmed case of CWD in Michigan was discovered in an infected deer on an enclosed deer-breeding facility. It is also found in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

In February 2011, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources reported the first confirmed case of the disease in that state. The affected animal was a white-tailed deer killed by a hunter.[44]

CWD has also been diagnosed in farmed elk and deer herds in a number of states and in two Canadian provinces. The first positive farmed-elk herd in the United States was detected in 1997 in South Dakota. Since then, additional positive elk herds and farmed white-tailed deer herds have been found in South Dakota (7), Nebraska (4), Colorado (10), Oklahoma (1), Kansas (1), Minnesota (3), Montana (1), Wisconsin (6), and New York (2). As of fall of 2006, four positive elk herds in Colorado and a positive white-tailed deer herd in Wisconsin remain under state quarantine. All of the other herds have been depopulated or have been slaughtered and tested, and the quarantine has been lifted from one herd that underwent rigorous surveillance with no further evidence of disease. CWD also has been found in farmed elk in the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta. A retrospective study also showed mule deer exported from Denver to the Toronto Zoo in the 1980s were affected. In June 2015, the disease was detected in a male white-tailed deer on a breeding ranch in Medina County, Texas. State officials euthanized 34 deer in an effort to contain a possible outbreak.

In February 2018, the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks announced that a Mississippi deer tested positive for chronic wasting disease.[45] Another Mississippi whitetail euthanized in Pontotoc County on 8 October 2018 tested positive for CWD. The disease was confirmed by the National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa on 30 October 2018.[46]

Species that have been affected with CWD include elk, mule deer, white-tailed deer, black-tailed deer, and moose. Other ruminant species, including wild ruminants and domestic cattle, sheep, and goats, have been housed in wildlife facilities in direct or indirect contact with CWD-affected deer and elk, with no evidence of disease transmission. However, experimental transmission of CWD into other ruminants by intracranial inoculation does result in disease, suggesting only a weak molecular species barrier exists. Research is ongoing to further explore the possibility of transmission of CWD to other species.

By April 2016, CWD had been found in captive animals in South Korea; the disease arrived there with live elk that were imported from Canada for farming in the late 1990s.[2][47]

In the summer of 2018, cases were discovered in the Harpur Farm herd in Grenville-sur-la-Rouge, Quebec.[26]

Over the course of 2018 fully 12% of the mule deer that were tested in Alberta, had a positive result. More than 8% of Alberta deer were deemed seropositive.[30]

Europe

In 2016, the first case of CWD in Europe was from the Nordfjella wild reindeer herd in southern Norway. Scientists found the diseased female reindeer as it was dying, and routine CWD screening at necropsy was unexpectedly positive. The origin of CWD in Norway is unknown, whereas import of infected deer from Canada was the source of CWD cases in South Korea. Norway has strict legislation and rules not allowing importation of live animals and cervids into the country. Norway has a scrapie surveillance program since 1997; while no reports of scrapie within the range of Nordfjella reindeer population have been identified, sheep are herded through that region and are a potential source of infection.[48]

In May and June 2016, two infected wild moose (Alces alces) were found around 300 km north from the first case, in Selbu.[49][50] By the end of August, a fourth case had been confirmed in a wild reindeer shot in the same area as the first case in March.[51]

In 2017, the Environment Agency of the Norwegian government released guidelines for hunters hunting reindeer in the Nordfjella areas. The guidelines contain information on identifying animals with CWD symptoms and instructions for minimizing the risk of contamination, as well as a list of supplies given to hunters to be used for taking and submitting samples from shot reindeer.[52]

In March 2018, Finnish Food Safety Authority EVIRA stated that the first case of CWD in Finland had been diagnosed in a 15-year-old moose (Alces alces) that had died naturally in the municipality of Kuhmo in the Kainuu region. Before this case in Kuhmo, Norway was the only country in the European Economic Area where CWD has been diagnosed. The moose did not have the transmissible North American form of the disease, but similar to the Norwegian variant of CWD, an atypical or sporadic form which occurs incidentally in individual animals of the deer family. In Finland, CWD screening of fallen wild cervids has been done since 2003. None of the roughly 2,500 samples analyzed so far have tested positive for the disease. The export of live animals of the deer family to other countries has been temporarily banned as a precautionary measure to stop the spread of the CWD, and moose hunters are going to be provided with more instructions before the start of the next hunting season, if appropriate. The export and sales of meat from deer will not be restricted and moose meat is considered safe to eat as only the brain and nervous tissue of infected moose contains prions.[53]

In March 2019, the Swedish National veterinary institute SVA diagnosed the first case of CWD in Sweden. A 16-year old emaciated female moose was found in the municipality of Arjeplog in the county of Norrbotten, circling and with loss of shyness towards humans, possibly blind. The moose was euthanized and the head was sent for CWD screening in the national CWD surveillance program. The brainstem tissue, but not lymph nodes, was positive for CWD (confirmed with Western Blot). A second case of CWD was diagnosed in May 2019, with very similar case history, about 70 km east of the first case. This second case, in the municipality of Arvidsjaur, was also an emaciated and apathic 16-year-old female moose that was euthanized. The circumstances of these Swedish cases are similar to the CWD cases in moose in both Norway and Finland. The EU regulated CWD surveillance runs between 2018 - 2020. A minimum of 6 000 cervids are to be tested, both free-ranging cervids, farmed red deer, and semi-domesticated reindeer.[54] The finding of CWD-positive moose initiated an intensified surveillance in the affected municipalities. Adult hunter-harvested moose and slaughtered semi-domesticated reindeer from the area are tested for CWD. In September 2019, a third moose was found positive for CWD, a hunter-harvested 10-year-old apparently healthy female moose from Arjeplog.[55]

Research

Research is focused on better ways to monitor disease in the wild, live animal diagnostic tests, developing vaccines, better ways to dispose of animals that died from the disease and to decontaminate the environment, where prions can persist in soils, and better ways to monitor the food supply. Deer harvesting and management issues are intertwined.[56]

See also

References

- "Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD)". USDA. APHIS. 1 August 2017.

- Patrice N Klein, CWD Program Manager USDA/APHIS. "Chronic Wasting Disease - APHIS Proposed Rule to Align BSE Import Regulations to OIE" (PDF). WHHCC Meeting – 5–6 February 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2014.

- "Transmission | Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) | Prion Disease | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-12-03. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "Distribution of Chronic Wasting Disease in North America". USGS.gov. 2019-01-31. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- "Occurrence | Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) | Prion Disease | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-02-25. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- Belay, E.D.; Maddox, R.A.; Williams, E.S.; Miller, M.W.; Gambetti, P.; Schonberger, L.B. (June 2004). "Chronic Wasting Disease and Potential Transmission to Humans". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (6): 977–984. doi:10.3201/eid1006.031082. PMC 3323184. PMID 15207045.

- "Chronic wasting disease - What to expect if your animals may be infected". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Haley, N. J.; Hoover, E. A. (2015). "Chronic wasting disease of cervids: Current knowledge and future perspectives". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 3: 305–25. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-111001. PMID 25387112.

- "Minnesota landfill to burn deer carcasses in effort to prevent CWD spread". wctrib.com. 8 October 2019.

- USGS National Wildlife Health Center Frequently asked questions concerning Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) Page last updated May 21, 2013; page accessed April 25, 2016

- Elevated silver, barium and strontium in antlers, vegetation and soils sourced from CWD cluster areas: do Ag/Ba/Sr piezoelectric crystals represent the transmissible pathogenic agent in TSEs? Purdey M. Med Hypotheses. 2004.

- "Another school of thought about what causes chronic wasting disease in deer". outdoornews.com. 17 December 2018.

- "AgCenter scientists makes historic CWD breakthrough | Sports". theadvocate.com. 2017-12-13. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- Warner, Darren (16 July 2018). "The War Over Explaining Chronic Wasting Disease". deeranddeerhunting.com.

- Johnson, Chad J.; Herbst, Allen; Duque-Velasquez, Camilo; Vanderloo, Joshua P.; Bochsler, Phil; Chappell, Rick; McKenzie, Debbie (2011). "Prion Protein Polymorphisms Affect Chronic Wasting Disease Progression". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e17450. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617450J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017450. PMC 3060816. PMID 21445256.

- "Maladie débilitante chronique: le public exposé à des risques". La Presse (2018) Inc. 31 July 2019.

- Prusiner, Stanley B. (2001). "Neurodegenerative Diseases and Prions". New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (20): 1516–1526. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105173442006. PMID 17098992.

- Saunders, S.E.; Bartelt-Hunt, S.L.; Bartz, J.C. (2012). "Occurrence, transmission, and zoonotic potential of chronic wasting disease". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (3): 369–376. doi:10.3201/eid1803.110685. PMC 3309570. PMID 22377159.

- Selariu, A.; Powers, J.G.; Nalls, A.; Brandhuber, M.; Mayfield, A...&; Mathiason, C.K. (2015). "In utero transmission and tissue distribution of chronic wasting disease-associated prions in free-ranging Rocky Mountain elk". Journal of General Virology. 96 (11): 3444–55. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000281. PMC 4806583. PMID 26358706.

- Williams, E.S.; Young, S. (1980). "Chronic wasting disease of captive mule deer: A Spongiform Encepalopathy". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 16 (1): 89–98. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-16.1.89. PMID 7373730.

- Wisniewski, T.; Goni, F. (2012). "Could immodulation be used to prevent prion diseases?". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 10 (3): 307–317. doi:10.1586/eri.11.177. PMC 3321512. PMID 22397565.

- Mitchell, Gordon B.; Sigurdson, Christina J.; O’Rourke, Katherine I.; Algire, James; Harrington, Noel P.; Walther, Ines; Spraker, Terry R.; Balachandran, Aru (2012-06-18). "Experimental Oral Transmission of Chronic Wasting Disease to Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus)". PLoS ONE. 7 (6): e39055. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...739055M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039055. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3377593. PMID 22723928.

- Nichols, Tracy A.; Spraker, Terry R.; Rigg, Tara D.; Meyerett-Reid, Crystal; Hoover, Clare; Michel, Brady; Bian, Jifeng; Hoover, Edward; Gidlewski, Thomas; Balachandran, Aru; O'Rourke, Katherine; Telling, Glenn C.; Bowen, Richard; Zabel, Mark D.; Vercauteren, Kurt C. (2013). "Intranasal Inoculation of White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) with Lyophilized Chronic Wasting Disease Prion Particulate Complexed to Montmorillonite Clay". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e62455. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862455N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062455. PMC 3650006. PMID 23671598.

- Fischer, J.W.; Phillips, G.E.; Nichols, T.A.; Vercauteren, K.C. (2013). "Could avian scavengers translocated infectious prions to disease-free areas initiating new foci of chronic wasting disease?". Prion. 7 (4): 263–266. doi:10.4161/pri.25621. PMC 3904308. PMID 23822910.

- Vercauteren, K.C.; Pilon, J.L.; Nash, P.B.; Phillips, G.E.; Fischer, J.W. (2012). "Prion remains infectious after passage through digestive system of American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos)". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e45774. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745774V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045774. PMC 3474818. PMID 23082115.

- Lorange, Simon-Olivier. "Pourquoi avoir abattu 3000 cerfs dans les Laurentides? | Simon-Olivier Lorange | Environnement". La Presse. Lapresse.ca. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- "DU CERF DE BOILEAU, IL N'Y EN AURA PLUS". La Presse, ltée. 21 December 2018.

- "Une maladie fatale affectant les cerfs arrive au Québec". La Presse (2018) Inc. 1 October 2018.

- "Deer hunting rules relaxed to curb deadly disease". CBC. 9 September 2019.

- "Critics warn of 'totally unacceptable' risk to humans after meat from 21 tainted elk herds enters food supply". CBC. 15 August 2019.

- "Operation to control and monitor chronic wasting disease in cervids". mffp.gouv.qc.ca. 29 August 2019.

- Prusiner, Stanley B. (2001). "Neurodegenerative Diseases and Prions". New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (20): 1516–1526. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105173442006. PMID 11357156.

- Wolfe, Lisa L.; Conner, Mary M.; Baker, Thomas H.; Dreitz, Victoria J.; Burnham, Kenneth P.; Williams, Elizabeth S.; Hobbs, N. Thompson; Miller, Michael W. (2002). "Evaluation of Antemortem Sampling to Estimate Chronic Wasting Disease Prevalence in Free-Ranging Mule Deer". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 66 (3): 564. doi:10.2307/3803124. JSTOR 3803124.

- "Chronic Wasting Disease" (PDF).

- Geremia, Chris; Hoeting, Jennifer A.; Wolfe, Lisa L.; Galloway, Nathan L.; Antolin, Michael F.; Spraker, Terry R.; Miller, Michael W.; Hobbs, N. Thompson (2015). "Age and Repeated Biopsy Influence Antemortem PRPCWD Testing in Mule Deer (Odocoileus Hemionus) in Colorado, USA". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 51 (4): 801–810. doi:10.7589/2014-12-284. ISSN 0090-3558. PMID 26251986.

- Thomsen, Bruce V.; Schneider, David A.; O’Rourke, Katherine I.; Gidlewski, Thomas; McLane, James; Allen, Robert W.; McIsaac, Alex A.; Mitchell, Gordon B.; Keane, Delwyn P. (September 2012). "Diagnostic accuracy of rectal mucosa biopsy testing for chronic wasting disease within white-tailed deer ( Odocoileus virginianus ) herds in North America: Effects of age, sex, polymorphism at PRNP codon 96, and disease progression". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 24 (5): 878–887. doi:10.1177/1040638712453582. ISSN 1040-6387. PMID 22914819.

- Spraker, Terry R.; VerCauteren, Kurt C.; Gidlewski, Thomas; Schneider, David A.; Munger, Randy; Balachandran, Aru; O'Rourke, Katherine I. (2009). "Antemortem Detection of PrP CWD in Preclinical, Ranch-Raised Rocky Mountain Elk ( Cevvus Elaphus Nelsoni ) by Biopsy of the Rectal Mucosa". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 21 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1177/104063870902100103. ISSN 1040-6387. PMID 19139496.

- Monello, Ryan J.; Powers, Jenny G.; Hobbs, N. Thompson; Spraker, Terry R.; O’Rourke, Katherine I.; Wild, Margaret A. (April 2013). "Efficacy of Antemortem Rectal Biopsies to Diagnose and Estimate Prevalence of Chronic Wasting Disease in Free-Ranging Cow Elk (Cervus Elaphus Nelsoni)". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 49 (2): 270–278. doi:10.7589/2011-12-362. ISSN 0090-3558. PMID 23568902.

- "Study Shows Prions Stick Around In Certain Soils". Science Daily. September 17, 2003. Retrieved October 23, 2006.

- "New Research Supports Theory That Indirect Transmission Of Chronic Wasting Disease Possible In Mule Deer". Science Daily. May 19, 2004. Retrieved October 23, 2006.

- Mathiason CK, Powers JG, Dahmes SJ, Osborn DA, Miller KV, Warren RJ, Mason GL, Hays SA, Hayes-Klug J, Seelig DM, Wild MA, Wolfe LL, Spraker TR, Miller MW, Sigurdson CJ, Telling GC, Hoover EA (October 6, 2006). "Infectious prions in the saliva and blood of deer with chronic wasting disease". Science. 314 (5796): 133–6. Bibcode:2006Sci...314..133M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.400.9381. doi:10.1126/science.1132661. PMID 17023660.

- Ernest, Holly B.; Hoar, Bruce R.; Well, Jay A.; O'Rourke, Katherine I. (2010-04-01). "Molecular genealogy tools for white-tailed deer with chronic wasting disease". Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research. 74 (2): 153–156. ISSN 1928-9022. PMC 2851727. PMID 20592847.

- "Chronic Wasting Disease". West Virginia Division of Natural Resources. 2008-08-01.

- "Wasting Disease Confirmed in State". February 13, 2011.

- "The Clarion Ledger". The Clarion Ledger. 2018-02-10. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- Times Daily Florence, AL 11/12/18

- Rachel Becker for Nature News. April 18, 2016 Deadly animal prion disease appears in Europe

- Benestad, Sylvie L.; Mitchell, Gordon; Simmons, Marion; Ytrehus, Bjørnar; Vikøren, Turid (2016-01-01). "First case of chronic wasting disease in Europe in a Norwegian free-ranging reindeer". Veterinary Research. 47 (1): 88. doi:10.1186/s13567-016-0375-4. ISSN 0928-4249. PMC 5024462. PMID 27641251.

- "Chronic Wasting Disease in Norway". Norwegian Food Safety Authority. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- Norwegian Food Safety Authority. Chronic Wasting Disease in Norway. Published July 13, 2016; updated July 14, 2016

- "Nytt tilfelle av CWD på villrein". Norwegian Veterinary Institute (in Norwegian). 29 August 2016. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- "Informasjon til villreinjegere i Nordfjella" (PDF) (in Norwegian). 2017. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- "Moose found dead in forest with chronic wasting disease". Evira. 8 March 2018. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- https://www.sva.se/om-sva/pressrum/nyheter-fran-sva/avmagringssjuka-cwd-upptackt-pa-alg-i-norrbottens-lan

- https://www.sva.se/om-sva/pressrum/nyheter-fran-sva/avmagringssjuka-nu-bekraftat-pa-algen-i-arjeplog

- Lohrer, Lydia (November 26, 2017). "Hunters must change approach, help stall CWD from spreading to humans". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chronic wasting disease. |

- This entry incorporates public domain text originally at What is chronic wasting disease? Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

- Chronic Wasting Disease Alliance

- Chronic wasting disease (CWD) of deer and elk, Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- Chronic wasting disease (CWD) USGS National Wildlife Health Center

- CWD information & testing Colorado Parks and Wildlife

- Chronic wasting disease Illinois Department of Natural Resources

- Chronic wasting disease management Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

- Chronic wasting disease (CWD) Nebraska Game and Parks Commission

- Chronic wasting disease New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

- Chronic wasting disease Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

- Chronic wasting disease (CWD) Wyoming Wildlife, Wyoming Game and Fish