Kuru (disease)

Kuru is a very rare, incurable and fatal neurodegenerative disorder that was formerly common among the Fore people of Papua New Guinea. Kuru is a form of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) caused by the transmission of abnormally folded proteins (prion proteins), which leads to symptoms such as tremors and loss of coordination from neurodegeneration.

| Kuru | |

|---|---|

| |

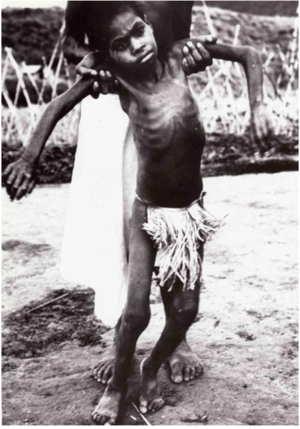

| A Fore child with advanced kuru | |

| Specialty | Neuropathology |

| Symptoms | Body tremors, random outbursts of laughter, gradual loss of coordination |

| Duration | 11–14 months[1] |

| Causes | Transmission of infected prion proteins |

| Risk factors | Coming into close contact with the brain of an infected individual |

| Diagnostic method | Neurological examination |

| Differential diagnosis | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| Prevention | Avoid practices of cannibalism |

| Treatment | None |

| Medication | None |

| Prognosis | Always fatal |

| Frequency | 2,700 (1957–2004) |

| Deaths | Approximately 2,700 |

The term kuru derives from the Fore word kuria or guria ("to shake"),[2] due to the body tremors that are a classic symptom of the disease and kúru itself means "trembling".[3] It is also known as the "laughing sickness" due to the pathologic bursts of laughter which are a symptom of the disease. It is now widely accepted that kuru was transmitted among members of the Fore tribe of Papua New Guinea via funerary cannibalism. Deceased family members were traditionally cooked and eaten, which was thought to help free the spirit of the dead.[4] Women and children usually consumed the brain, the organ in which infectious prions were most concentrated, thus allowing for transmission of kuru. The disease was therefore more prevalent among women and children.

The epidemic likely started when a villager developed sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and died. When villagers ate the brain, they contracted the disease, and it was then spread to other villagers who ate their infected brains.[5]

While the Fore people stopped consuming human meat in the early 1960s, when it was first speculated to be transmitted via endocannibalism, the disease lingered due to kuru's long incubation period of anywhere from 10 to over 50 years.[6] The epidemic declined sharply after discarding cannibalism, from 200 deaths per year in 1957 to 1 or no deaths annually in 2005, with sources disagreeing on whether the last known kuru victim died in 2005 or 2009.[7][8][9][10]

Signs and symptoms

Kuru, a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, is a disease of the nervous system that causes physiological and neurological effects which ultimately lead to death. It is characterized by progressive cerebellar ataxia, or loss of coordination and control over muscle movements.[11][12]

The preclinical or asymptomatic phase, also called the incubation period, averages 10–13 years, but can be as short as 5 and has been estimated to last as long as 50 years or more after initial exposure.[13]

The clinical stage, which begins at the first onset of symptoms, lasts an average of 12 months. The clinical progression of kuru is divided into three specific stages: the ambulant, sedentary and terminal stages. While there is some variation in these stages between individuals, they are highly conserved among the affected population.[11] Before the onset of clinical symptoms, an individual can also present with prodromal symptoms including headache and joint pain in the legs.[14]

In the first (ambulant) stage, the infected individual may exhibit unsteady stance and gait, decreased muscle control, tremors, difficulty pronouncing words (dysarthria), and titubation. This stage is named the ambulant because the individual is still able to walk around despite symptoms.[14]

In the second (sedentary) stage, the infected individual is incapable of walking without support and suffers ataxia and severe tremors. Furthermore, the individual shows signs of emotional instability and depression, yet exhibits uncontrolled and sporadic laughter. Despite the other neurological symptoms, tendon reflexes are still intact at this stage of the disease.[14]

In the third and final (terminal) stage, the infected individual's existing symptoms, like ataxia, progress to the point where they are no longer capable of sitting without support. New symptoms also emerge: the individual develops dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, which can lead to severe malnutrition. They may also become incontinent, lose the ability or will to speak and become unresponsive to their surroundings, despite maintaining consciousness.[14] Towards the end of the terminal stage, patients often develop chronic ulcerated wounds that can be easily infected. An infected person usually dies within three months to two years after the first terminal stage symptoms, often because of pneumonia or infection.[15]

Causes

Kuru is largely localized to the Fore people and people with whom they intermarried.[16] The Fore people ritualistically cooked and consumed body parts of their family members following their death to symbolize respect and mourning. Because the brain is the organ enriched in the infectious agent prion, women and children, who consumed brain and viscera, had much higher likelihood of being infected than men, who preferentially consumed muscles.[17]

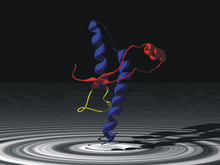

Prion

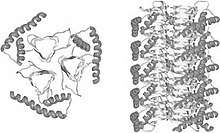

The infectious agent is a misfolded form of a host-encoded protein called prion (PrP). Prion proteins are encoded by the Prion Protein Gene (PRNP).[19] The two forms of prion are designated as PrPc, which is a normally folded protein, and PrPsc, a misfolded form which gives rise to the disease. The two forms do not differ in their amino acid sequence; however, the pathogenic PrPsc isoform differs from the normal PrPc form in its secondary and tertiary structure. The PrPsc isoform is more enriched in beta sheets, while the normal PrPc form is enriched in alpha helices.[17] The differences in conformation allow PrPsc to aggregate and be extremely resistant to protein degradation by enzymes or by other chemical and physical means. The normal form, on the other hand, is susceptible to complete proteolysis and soluble in non-denaturing detergents.[14]

It has been suggested that pre-existing or acquired PrPsc can promote the conversion of PrPc into PrPsc, which goes on to convert other PrPc. This initiates a chain reaction that allows for its rapid propagation, resulting in the pathogenesis of prion diseases.[14]

Transmission

In 1961, Australian Michael Alpers conducted extensive field studies among the Fore accompanied by anthropologist Shirley Lindenbaum.[9] Their historical research suggested the epidemic may have originated around 1900 from a single individual who lived on the edge of Fore territory and who is thought to have spontaneously developed some form of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[20] Alpers and Lindenbaum's research conclusively demonstrated that kuru spread easily and rapidly in the Fore people due to their endocannibalistic funeral practices, in which relatives consumed the bodies of the deceased to return the "life force" of the deceased to the hamlet, a Fore societal subunit.[21] Corpses of family members were often buried for days, then exhumed once the corpses were infested with maggots, at which point the corpse would be dismembered and served with the maggots as a side dish.[22]

The demographic distribution evident in the infection rates – kuru was eight to nine times more prevalent in women and children than in men at its peak – is because Fore men considered consuming human flesh to weaken them in times of conflict or battle, while the women and children were more apt to eat the bodies of the deceased, including the brain, where the prion particles were particularly concentrated. Also, the strong possibility exists that it was passed on to women and children more easily because they took on the task of cleaning relatives after death and may have had open sores and cuts on their hands.[23]

Although ingestion of the prion particles can lead to the disease,[24] a high degree of transmission occurred if the prion particles could reach the subcutaneous tissue. With elimination of cannibalism because of Australian colonial law enforcement and the local Christian missionaries' efforts, Alpers' research showed that kuru was already declining among the Fore by the mid‑1960s. However, the mean incubation period of the disease is 14 years, and 7 cases were reported with latencies of 40 years or more for those who were most genetically resilient, continuing to appear for several more decades. Sources disagree on whether the last sufferer died in 2005 or 2009.[9][10][7][8]

Immunity

In 2009, researchers at the Medical Research Council discovered a naturally occurring variant of a prion protein in a population from Papua New Guinea that confers strong resistance to kuru. In the study, which began in 1996,[25] researchers assessed over 3,000 people from the affected and surrounding Eastern Highland populations, and identified a variation in the prion protein G127.[26] G127 polymorphism is the result of a missense mutation, and is highly geographically restricted to regions where the kuru epidemic was the most widespread. Researchers believe that the PrnP variant occurred very recently, estimating that the most recent common ancestor lived 10 generations ago.[26][27]

Of the discovery, Professor John Collinge, director of the MRC's Prion Unit at University College London, has stated that:

It's absolutely fascinating to see Darwinian principles at work here. This community of people has developed their own biologically unique response to a truly terrible epidemic. The fact that this genetic evolution has happened in a matter of decades is remarkable.

— John Collinge, Medical Research Council

The findings of the study could help researchers better understand and develop treatments for other related prion diseases, such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease[25] and Alzheimer's disease.[28]

History

Initially, the Fore people believed the causes of kuru to be sorcery or witchcraft, while patrol officers believed that kuru might be psychosomatic, or caused by mental factors.[29] The Fore people also thought that the magic causing kuru was contagious. Another theory was that cassowary disease, also known as negi-negi, was the cause. This disease, the Fore people believed, was caused by ghosts because of the shaking and strange behaviour that comes with kuru. Attempting to cure this, they would feed victims pork and casuarinas bark. Prior to the late 1950s, patrol officers thought that kuru was psychosomatic and was caused by the trauma of Western colonization and perpetuated by beliefs in sorcery and witchcraft. It was not until 1957 that cannibalism was investigated by Gajdusek and shown with data to be the cause. However, action was not considered a priority because the link to cannibalism was thought to be either too unusual, or that there was insufficient evidence linking kuru to cannibalism. Cannibalism, however, was a reasonable enough explanation for kuru that the Australian administration banned the practice of feasting on the dead, and cannibalism was nearly eliminated by 1960. While the number of cases of kuru was decreasing, those in medical research were able to properly investigate kuru, which led to the modern proposition of prions being the cause.[30]

Kuru was first described in official reports by Australian officers patrolling the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea in the early 1950s.[31] Some unofficial accounts place kuru in the region as early as 1910.[7] In 1951, Arthur Carey was the first to use the term 'kuru' in a report to describe a new disease afflicting the Fore tribes of Papua New Guinea. In his report, Carey noted that kuru mostly afflicted Fore women, eventually killing them. In 1953, kuru was observed by patrol officer John McArthur who provided a description of the disease in his report. McArthur believed that kuru was merely a psychological episode resulting from the confirmed sorcery practices of the tribal people in the region.[31]

Kuru was first noted in the Fore, Yate and Usurufa people in 1952-1953 by anthropologists Ronald Berndt and Catherine Berndt. However, it was not until 1957, when the Kuru disease had become an epidemic, that Daniel Carleton Gajdusek, a virologist, and Vincent Zigas, a medical doctor, first started research on the disease. After the disease had festered into a bigger epidemic the tribal people asked Charles Pfarr, a Lutheran Medical Officer to come to the area to report the disease to Australian authorities.[7]

In an effort to understand the pathology of Kuru disease, Gajdusek established the first experimental tests on chimpanzees for Kuru at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The method of the experiments was to introduce kuru brain material to the closest human relative, the chimpanzee, and to document the behaviours of the animal until death or a negative outcome occurred.[7] Michael Alpers, an Australian doctor, collaborated with Gajdusek by providing samples of brain tissues he had taken from an 11-year-old Fore girl who had died of Kuru. In his work, Gajdusek was also the first to compile a bibliography of the Kuru disease. Joe Gibbs joined Gajdusek to monitor and record the behavior of the apes and conduct autopsies. Within two years, one of the chimps, Daisy, had developed kuru, demonstrating that an unknown disease factor was transmitted through infected biomaterial and that it was capable of crossing the species barrier to other primates. After Elisabeth Beck confirmed that this experiment brought about the first conducted transmission of Kuru, the finding was deemed a very important advancement in human medicine leading to the award of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Daniel Carleton Gajdusek in 1976.[7]

Subsequently, E. J. Field spent large parts of the late 1960s and early 1970s in New Guinea investigating the disease,[32] connecting it to scrapie and multiple sclerosis.[33] He noted similarities in the diseases interactions with glial cells, including the critical observation that the infectious process may depend on structural rearrangement of the host's molecules.[34] This was an early observation of what was to later become the prion hypothesis.[35]

In literature

The Czech immunologist-poet Miroslav Holub wrote 'Kuru, or the Smiling Death Syndrome' about the disease.[36]

See also

- Boone Helm

- Cannibalism

- Donner Party

- Endocannibalism

- Exocannibalism

- List of incidents of cannibalism

References

- "The epidemiology of kuru in the period 1987 to 1995", Department of Health (Australia), retrieved February 5, 2019

- Hoskin, J. O.; Kiloh, L. G.; Cawte, J. E. (1969-04-01). "Epilepsy and Guria: the shaking syndromes of New Guinea". Social Science & Medicine. 3 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1016/0037-7856(69)90037-7. ISSN 0037-7856. PMID 5809623.

- Scott, Graham (1978). The Fore language of Papua New Guinea. (Pacific Linguistics, Series B No.47) (PDF). Canberra: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. pp. 2, 6.

- Whitfield, Jerome T.; Pako, Wandagi H.; Collinge, John; Alpers, Michael P. (2008-11-27). "Mortuary rites of the South Fore and kuru". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1510): 3721–3724. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0074. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2581657. PMID 18849288.

- Bichell, Rae Ellen (September 6, 2016). "When People Ate People, A Strange Disease Emerged". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- "Kuru". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- Alpers, Michael P. (2007). "A history of kuru". Papua and New Guinea Medical Journal. 50 (1–2): 10–19. ISSN 0031-1480. PMID 19354007.

- Rense, Sarah (September 7, 2016). "Here's What Happens to Your Body When You Eat Human Meat". Esquire.

- "A life of determination". Monash University — Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences. 2009-02-23. Archived from the original on 2015-12-10. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Collinge, John; Whitfield, Jerome; McKintosh, Edward; Beck, John; Mead, Simon; Thomas, Dafydd; Alpers, Michael (2006-06-24). "Kuru in the 21st century—an acquired human prion disease with very long incubation periods". The Lancet. 367 (9528): 2068–2074. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68930-7. PMID 16798390.

- Alpers, Michael P (December 2005). "The epidemiology of kuru in the period 1987 to 1995". Communicable Diseases Intelligence. 29 (4): 391–399. PMID 16465931. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- Liberski, P (February 2012). "Kuru: genes, cannibals and neuropathology". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 71 (2): 92–103. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182444efd. PMC 5120877. PMID 22249461.

- Collinge, John; Whitfield, Jerome; McKintosh, Edward; Frosh, Adam; Mead, Simon; Hill, Andrew F.; Brandner, Sebastian; Thomas, Dafydd; Alpers, Michael P. (2008-11-27). "A clinical study of kuru patients with long incubation periods at the end of the epidemic in Papua New Guinea". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1510): 3725–3739. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0068. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2581654. PMID 18849289.

- Imran, Muhammad; Mahmood, Saqib (2011-01-01). "An overview of human prion diseases". Virology Journal. 8: 559. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-559. ISSN 1743-422X. PMC 3296552. PMID 22196171.

- Wadsworth JD, Joiner S, Linehan JM, et al. (March 2008). "Kuru prions and sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease prions have equivalent transmission properties in transgenic and wild-type mice". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (10): 3885–90. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.3885W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800190105. PMC 2268835. PMID 18316717.

- Lindenbaum, Shirley (2001-01-01). "Kuru, Prions, and Human Affairs: Thinking About Epidemics". Annual Review of Anthropology. 30 (1): 363–385. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.363.

- "Kuru: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". Diseases & Conditions — Medscape Reference. 2016-04-27.

- Kupfer, L; Hinrichs, W; Groschup, M.H (2016-11-10). "Prion Protein Misfolding". Current Molecular Medicine. 9 (7): 826–835. doi:10.2174/156652409789105543. ISSN 1566-5240. PMC 3330701. PMID 19860662.

- Linden, Rafael; Martins, Vilma R.; Prado, Marco A. M.; Cammarota, Martín; Izquierdo, Iván; Brentani, Ricardo R. (2008-04-01). "Physiology of the Prion Protein". Physiological Reviews. 88 (2): 673–728. doi:10.1152/physrev.00007.2007. ISSN 0031-9333. PMID 18391177.

- Kuru: The Science and the Sorcery (Siamese Films, 2010)

- Diamond J.M. (1997). Guns, germs, and steel: the fates of human societies. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-393-03891-0.

- Liberski, P. P. (2009). "Kuru: Its ramifications after fifty years" (PDF). Experimental Gerontology. 44 (1–2): 63–69. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2008.05.010. PMID 18606515.

- Paul A. Janson (2009-04-13). "Kuru". eMedicine. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- Gibbs CJ, Amyx HL, Bacote A, Masters CL, Gajdusek DC (August 1980). "Oral transmission of kuru, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, and scrapie to nonhuman primates". J. Infect. Dis. 142 (2): 205–208. doi:10.1093/infdis/142.2.205. PMID 6997404.

- "Brain disease 'resistance gene' evolves in Papua New Guinea community; could offer insights into CJD". ScienceDaily. 2009-11-21. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- Mead, Simon; Whitfield, Jerome; Poulter, Mark; Shah, Paresh; Uphill, James; Campbell, Tracy; Al-Dujaily, Huda; Hummerich, Holger; Beck, Jon (2009-11-19). "A Novel Protective Prion Protein Variant that Colocalizes with Kuru Exposure" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (21): 2056–2065. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809716. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 19923577.

- Mead, S.; Whitfield, J.; Poulter, M.; Shah, P.; Uphill, J.; Campbell, T.; Al-Dujaily, H.; Hummerich, H.; Beck, J.; Mein, C. A.; Verzilli, C.; Whittaker, J.; Alpers, M. P.; Collinge, J. (2009). "Supply file" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (21): 2056–65. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809716. PMID 19923577.

- "Natural genetic variation gives complete resistance in prion diseases". Ucl.ac.uk. 2015-06-11. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- "Kuru". Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies. Archived from the original on 2016-11-21. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- Kennedy, John (15 May 2012). "Kuru Among the Foré — The Role of Medical Anthropology in Explaining Aetiology and Epidermiology". ArcJohn.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- Shirley Lindenbaum (14 Apr 2015). "An annotated history of kuru". Medicine Anthropology Theory.

- "Kuru - To Tremble with Fear". Horizon. Season 8. Episode 6. 22 February 1971. BBC2.

- Field, EJ (7 Dec 1967). "The significance of astroglial hypertrophy in Scrapie, Kuru, Multiple Sclerosis and old age together with a note on the possible nature of the scrapie agent". Journal of Neurology. 192 (3): 265–274. doi:10.1007/bf00244170.

- Field, EJ (Feb 1978). "Immunological assessment of ageing: emergence of scrapie-like antigens". Age Ageing. 7 (1): 28–39. doi:10.1093/ageing/7.1.28. PMID 416662.

- Peat, Ray. "BSE - mad cow - scrapie, etc.: Stimulated amyloid degeneration and the toxic fats". RayPeat.com.

- Holub, Miroslav,Vanishing Lung Syndrome, trans. David Young and Dana Habova (Oberlin College Press, 1990). ISBN 0-932440-52-5; (Faber and Faber, 1990). ISBN 0-571-14339-3

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |