Bioequivalence

Bioequivalence is a term in pharmacokinetics used to assess the expected in vivo biological equivalence of two proprietary preparations of a drug. If two products are said to be bioequivalent it means that they would be expected to be, for all intents and purposes, the same.

Birkett (2003) defined bioequivalence by stating that, "two pharmaceutical products are bioequivalent if they are pharmaceutically equivalent and their bioavailabilities (rate and extent of availability) after administration in the same molar dose are similar to such a degree that their effects, with respect to both efficacy and safety, can be expected to be essentially the same. Pharmaceutical equivalence implies the same amount of the same active substance(s), in the same dosage form, for the same route of administration and meeting the same or comparable standards."[1]

For The World Health Organization (WHO) "two pharmaceutical products are bioequivalent if they are pharmaceutically equivalent or pharmaceutical alternatives, and their bioavailabilities, in terms of rate (Cmax and tmax) and extent of absorption (area under the curve), after administration of the same molar dose under the same conditions, are similar to such a degree that their effects can be expected to be essentially the same" [2].

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has defined bioequivalence as, "the absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active ingredient or active moiety in pharmaceutical equivalents or pharmaceutical alternatives becomes available at the site of drug action when administered at the same molar dose under similar conditions in an appropriately designed study."[3]

Bioequivalence

In determining bioequivalence, for example, between two products such as a commercially available Brand product and a potential to-be-marketed Generic product, pharmacokinetic studies are conducted whereby each of the preparations are administered in a cross-over study to volunteer subjects, generally healthy individuals but occasionally in patients. Serum/plasma samples are obtained at regular intervals and assayed for parent drug (or occasionally metabolite) concentration. Occasionally, blood concentration levels are neither feasible or possible to compare the two products (e.g. inhaled corticosteroids), then pharmacodynamic endpoints rather than pharmacokinetic endpoints (see below) are used for comparison. For a pharmacokinetic comparison, the plasma concentration data are used to assess key pharmacokinetic parameters such as area under the curve (AUC), peak concentration (Cmax), time to peak concentration (Tmax), and absorption lag time (tlag). Testing should be conducted at several different doses, especially when the drug displays non-linear pharmacokinetics.

In addition to data from bioequivalence studies, other data may need to be submitted to meet regulatory requirements for bioequivalence. Such evidence may include:

- analytical method validation

- in vitro-in vivo correlation studies (IVIVC)

Regulatory definition

The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization considers two formulation bioequivalent if the 90% confidence interval for the ratio multisource (generic) product/comparator lie within 80.00-125.00% acceptance range for AUC0–t and Cmax. For high variable finished pharmaceutical products, the applicable acceptance range for Cmax can be 69.84-143.19% [4].

Australia

In Australia, the Therapeutics Goods Administration (TGA) considers preparations to be bioequivalent if the 90% confidence intervals (90% CI) of the rate ratios, between the two preparations, of Cmax and AUC lie in the range 0.80–1.25. Tmax should also be similar between the products.[1]

There are tighter requirements for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index and/or saturable metabolism – thus no generic products exist on the Australian market for digoxin or phenytoin for instance.

Europe

According to regulations applicable in the European Economic Area[5] two medicinal products are bioequivalent if they are pharmaceutically equivalent or pharmaceutical alternatives and if their bioavailabilities after administration in the same molar dose are similar to such a degree that their effects, with respect to both efficacy and safety, will be essentially the same. This is considered demonstrated if the 90% confidence intervals (90% CI) of the ratios for AUC0–t and Cmax between the two preparations lie in the range 80–125%.

United States

The FDA considers two products bioequivalent if the 90% CI of the relative mean Cmax, AUC(0–t) and AUC(0–∞) of the test (e.g. generic formulation) to reference (e.g. innovator brand formulation) should be within 80% to 125% in the fasting state. Although there are a few exceptions, generally a bioequivalent comparison of Test to Reference formulations also requires administration after an appropriate meal at a specified time before taking the drug, a so-called "fed" or "food-effect" study. A food-effect study requires the same statistical evaluation as the fasting study, described above.[3]

Bioequivalence issues

While the FDA maintains that approved generic drugs are equivalent to their branded counterparts, bioequivalence problems have been reported by physicians and patients for many drugs.[6] Certain classes of drugs are suspected to be particularly problematic because of their chemistry. Some of these include chiral drugs, poorly absorbed drugs, and cytotoxic drugs. In addition, complex delivery mechanisms can cause bioequivalence variances.[6] Physicians are cautioned to avoid switching patients from branded to generic, or between different generic manufacturers, when prescribing anti-epileptic drugs, warfarin, and levothyroxine.[7]

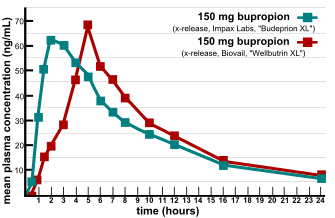

Major issues were raised in the verification of bioequivalence when multiple generic versions of FDA-approved generic drug were found not to be equivalent in efficacy and side effect profiles.[8] In 2007, two providers of consumer information on nutritional products and supplements, ConsumerLab.com and The People's Pharmacy, released the results of comparative tests of different brands of bupropion.[9] The People's Pharmacy received multiple reports of increased side effects and decreased efficacy of generic bupropion, which prompted it to ask ConsumerLab.com to test the products in question. The tests showed that some generic versions of Wellbutrin XL 300 mg didn't perform the same as the brand-name pill in laboratory tests.[10] The FDA investigated these complaints and concluded that the generic version is equivalent to Wellbutrin XL in regard to bioavailability of bupropion and its main active metabolite hydroxybupropion. The FDA also said that coincidental natural mood variation is the most likely explanation for the apparent worsening of depression after the switch from Wellbutrin XL to Budeprion XL.[11] After several years of denying patient reports, in 2012 the FDA reversed this opinion, announcing that "Budeprion XL 300 mg fails to demonstrate therapeutic equivalence to Wellbutrin XL 300 mg."[12] The FDA did not test the bioequivalence of any of the other generic versions of Wellbutrin XL 300 mg, but requested that the four manufacturers submit data on this question to the FDA by March 2013. As of October 2013, the FDA has made determinations on the formulations from some manufacturers not being bioequivalent.[13]

In 2004, Ranbaxy was revealed to have been falsifying data regarding the generic drugs they were manufacturing. As a result, 30 products were removed from US markets and Ranbaxy paid $500 million in fines. The FDA investigated many Indian drug manufacturers after this was discovered, and as a result at least 12 companies have been banned from shipping drugs to the US.[7]

See also

- Generic drug

- Pharmacokinetics

- Clinical trial

- Abbreviated New Drug Application

References

- Birkett DJ (2003). "Generics - equal or not?" (PDF). Aust Prescr. 26 (4): 85–7. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2003.063. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- WHO Guidance for organizations performing in vivo bioequivalence studies. WHO Technical Report Series No. 996, 2016, Annex 9

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2003). "Guidance for Industry: Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Studies for Orally Administered Drug Products — General Considerations" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration.

- WHO guidelines on Multisource (generic) pharmaceutical products: guidelines on registration requirements to establish interchangeability WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1003, 2017, Annex 6

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (20 January 2010). "Guideline on the Investigation of Bioequivalence" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- Midha KK, McKay G (2009). "Bioequivalence; its history, practice, and future". AAPS J. 11 (4): 664–70. doi:10.1208/s12248-009-9142-z. PMC 2782076. PMID 19806461.

- http://www.cell.com/trends/pharmacological-sciences/fulltext/S0165-6147(15)00241-2

- http://www.raps.org/focus-online/news/news-article-view/article/3794/

- "Generic drug equality questioned". Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Stenson, Jacqueline (12 October 2007). "Report questions generic antidepressant". NBC News. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Review of therapeutic equivalence: generic bupropion XL 300 mg and Wellbutrin XL 300 mg". Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- "Budeprion XL 300 mg not therapeutically equivalent to Wellbutrin XL 300 mg" (Press release). FDA. 3 October 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "FDA Update". FDA. October 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

External links

- Hussain AS, et al. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System: Highlights of the FDA's Draft Guidance Office of Pharmaceutical Science, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration.

- Rx index, specialized medical publication - online directory of drug bioequivalence. Intended exclusively for doctors of all specialties, pharmacists, clinical pharmacists, students of pharmaceutical faculties of higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of the III-IV level of accreditation, operators of the pharmaceutical market.

- Mills D (2005). Regulatory Agencies Do Not Require Clinical Trials To Be Expensive International Biopharmaceutical Association: IBPA Publications.

- FDA CDER Office of Generic Drugs – further U.S. information on bioequivalence testing and generic drugs

- Proposal to waive in vivo bioequivalence requirements for WHO Model List of Essential Medicines immediate-release, solid oral dosage forms. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 937, 2006, Annex 8.

- Guidance for organizations performing in vivo bioequivalence studies (revision). WHO Technical Report Series 996, 2016, Annex 9.

- General background notes and list of international comparator pharmaceutical products. WHO Technical Report Series 1003, 2017, Annex 5.

- WHO List of International Comparator products (September 2016)