We need you! Join our contributor community and become a WikEM editor through our open and transparent promotion process.

Seizure

From WikEM

This page covers seizures in general; refer to Status epilepticus for persistently seizing patients and seizure (peds) for pediatric patients.

Contents

Background

- Caused by a pathologic pattern of brain cortex activity → involuntary movement or change in level of consciousness[1]

- 11% of people will have at least one seizure in their lifetime

- 3% will have epilepsy (at least 2 unprovoked seizures)

- In pregnancy >20 WGA or <4wks postpartum, need to consider eclampsia

- Most seizures in pregnancy are not first-time seizures, but rather are due to medication noncompliance or pharmacokinetic drug changes as result of pregnancy

Seizure Types

Classification is based on the international classification from 1981[2]; More recent terms suggested by the ILAE (International League Against Epilepsy) task Force.[3]

Focal seizures

(Older term: partial seizures)

- Without impairment in consciousness– (AKA Simple partial seizures)

- With motor signs

- With sensory symptoms

- With autonomic symptoms or signs

- With psychic symptoms (including aura)

- With impairment in consciousness - (AKA Complex Partial Seizures--Older terms: temporal lobe or psychomotor seizures)

- Simple partial onset, followed by impairment of consciousness

- With impairment of consciousness at onset

- Focal seizures evolving to secondarily generalized seizures

- Simple partial seizures evolving to generalized seizures

- Complex partial seizures evolving to generalized seizures

- Simple partial seizures evolving to complex partial seizures evolving to generalized seizures

Generalized seizures

- Absence seizures (Older term: petit mal)

- Typical absence seizures

- Atypical absence seizures

- Myoclonic seizure

- Clonic seizures

- Tonic seizures

- Tonic–clonic seizures (Older term: grand mal)

- Atonic seizures

Clinical Features

- Abrupt onset, may be unprovoked

- Brief duration (typically <2min)

- AMS

- Jerking of limbs

- Postictal drowsiness/confusion

Seizure vs. Syncope[4]

- Factors that strongly favor seizure from most specific to least:

- Waking with cut tongue

- Abnormal behavior noted by bystanders

- LOC with emotional stress

- Postictal confusion

- Head turning to one side during LOC

- Prodromal deja vu or jamais vu

- Factors that predict against seizure

- Presyncopal spells

- Prodromal vertigo

- LOC with prolonged standing, sitting

- Diaphoresis, vertigo, nausea, chest pain, feeling of warmth, palpitations, dyspnea before spell

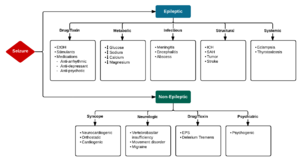

Differential Diagnosis

Seizure

- Epileptic seizure

- Non-epileptic seizure

- Intracranial mass

- Syncope

- Hyperventilation syndrome

- Migraine headache

- Movement disorders

- Narcolepsy/cataplexy

Evaluation

Physical

- Check for:

- Head / C-spine injuries

- Tongue/mouth lacs

- Sides of tongue (true seizure) more often bitten than tip of tongue (Psychogenic nonepileptiform seizures, formerly "pseudoseizure.")

- Tongue biting has sensitivity of ~25% and approaches 100% specificity in lateral tongue biting[5]

- Posterior shoulder dislocation

- Focal deficit (Todd paralysis vs CVA)

Work-Up

Known Epileptic with NO Change in Baseline Seizures

- Anticonvulsant drug concentration

- Fingerstick glucose

- Close out-patient follow-up

- Check for signs of trauma, cervical spine tenderness

- Consider head CT scan if suspicious of change in pattern, prolonged postictal period or trauma

New Seizure or Change in Baseline Seizures

- Consider: Pregnancy test, glucose, Electrolytes (Na, Ca, BUN, Crt), RPR, HIV, UA, EEG, lumbar puncture

- Always perform ECG as prolong QT and torsades can cause shaking after intermitent runs

- Non-contrast CT in ED or advanced imaging arranged as outpatient

- Neurology follow up or consult

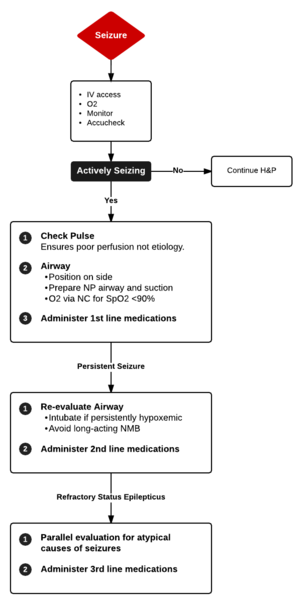

Management

- Protect patient from injury

- If possible, place patient in left lateral position to reduce risk of aspiration

- Do not place bite block!

- Benzodiazepine (Initial treatment of choice)[6]

- Secondary medications

- Fosphenytoin IV 20-30mg/kg at 150mg/min (may also be given IM)

- Contraindicated in pts w/ 2nd or 3rd degree AV block

- Valproic acid IV 20-40mg/kg at 5mg/kg/min

- Levetiracetam IV 60mg/kg, max 4500mg/dose

- Phenobarbital IV 20mg/kg at 50-75mg/min (be prepared to intubate)

- Fosphenytoin IV 20-30mg/kg at 150mg/min (may also be given IM)

- Refractory medications

- Consider

- Secondary causes of seizure (e.g. hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, INH toxicity, ecclampsia)

- Nonconvulsive seizures or status epilepticus - get EEG

Disposition

First Time Seizures

- Those with single generalized seizure and otherwise normal history and physical can be discharged home with close follow-up

- Observation is not unreasonable for those that look ill or have a complicating history/physical

- 24-hr recurrence of seizures in this group is about 9% when alcohol-related events are excluded[10]

- Instructions not to drive, swim, or participate in other potentially dangerous activities is important

See Also

- Anticonvulsants

- Anticonvulsant levels and reloading

- Seizure (peds)

- Febrile seizure

- Status epilepticus

External Links

References

- ↑ Martindale JL, Goldstein JN, Pallin DJ. Emergency department seizure epidemiology. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011 Feb;29(1):15-27.

- ↑ Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. From the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 1981; 22:489.

- ↑ Epilepsia 2015; 56:1515-1523.

- ↑ Sheldon R et al. Historical criteria that distinguish syncope from seizures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 Jul 3;40(1):142-8.

- ↑ Benbadis SR et al. Value of tongue biting in the diagnosis of seizures. Arch Intern Med. 1995 Nov 27;155(21):2346-9.

- ↑ Glauser T, et al. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children and adults: report of the guideline committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016; 16(1):48-61.

- ↑ McMullan J, Sasson C, Pancioli A, Silbergleit R: Midazolam versus diazepam for the treatment of status epilepticus in children and young adults: A meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17:575-582

- ↑ Legriel S, Oddo M, and Brophy GM. What’s new in refractory status epilepticus? Intensive Care Medicine. 2016:1-4.

- ↑ Mirsattari SM et al. Treatment of refractory status epilepticus with inhalational anesthetic agents isoflurane and desflurane. Arch Neurol. 2004 Aug;61(8):1254-9.

- ↑ Krumholz A, Wiebe S, Gronseth G, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure in adults (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2007; 69(21):1996-2007.