We need you! Join our contributor community and become a WikEM editor through our open and transparent promotion process.

Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia

From WikEM

Contents

Background

Definition[1][2]

- >3-5 consecutive beats originating below the AV node

- Rate > 100bpm

- Duration <30s

- Patient remains hemodynamically stable

Epidemiology

- Occurs in 0-4% of ambulatory patients

- Increased frequency in males and with increasing age

Clinical Features

- Often asymptomatic

- In some patients, NSVT is associated with an increased risk of sustained tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. In others it is of little prognostic significance.[3][4][5]

Differential Diagnosis

Most important distinction is whether dysrhythmia is associated with underlying structural heart disease.

NSVT in the absence of apparent structural heart disease

- Idiopathic Ventricular Tachycardia: Ventricular outflow arrhythmias (RVOT > LVOT). Good prognosis, rarely associated with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death (SCD).

- Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: Inherited or acquired long QT syndrome, familial catecholaminergic PMVT. Increased risk of SCD, consideration for ICD if symptomatic (syncope, arrest) or asymptomatic QTc > 550ms.

- Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy: Fibro-fatty deposition in RVIT/RVOT/RV apex. Increased risk of SCD, consideration for catheter ablation with ICD backup.

NSVT with apparent structural heart disease

- Hypertension and LVH: Occurrence of NSVT warrants evaluation for ischemic heart disease, aggressive medical management of hypertension (including beta-blockade). Prognosis unclear.

- Valvular disease: Highest incidence in AS and MR. No evidence that occurrence of NSVT associated with SCD.

- Ischemic heart disease: Monomorphic NSVT around myocardial scars, active ischemia associated with both mono/polymorphic VT and VF. In ED, early NSVT (<24h) after NSTEMI/STEMI common and not associated with adverse outcomes.

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Genetic myocardial disease, myocyte disarray produces arrhythmogenic substrate. NSVT associated with increased risk of SCD.

- Other conditions:

- Non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy

- Giant-cell myocarditis

- Repaired TOF

- Amyloidosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Chagas cardiomyopathy

Evaluation

In all patients:

- History: including arrhythmogenic medications/substances, pertinent family history

- Physical examination

- ECG/CXR

- TTE

In selected patients:

- Exercise testing

- Advanced imaging (CT/C-MR)

- Electrophysiologic studies

- Genetic testing

Management

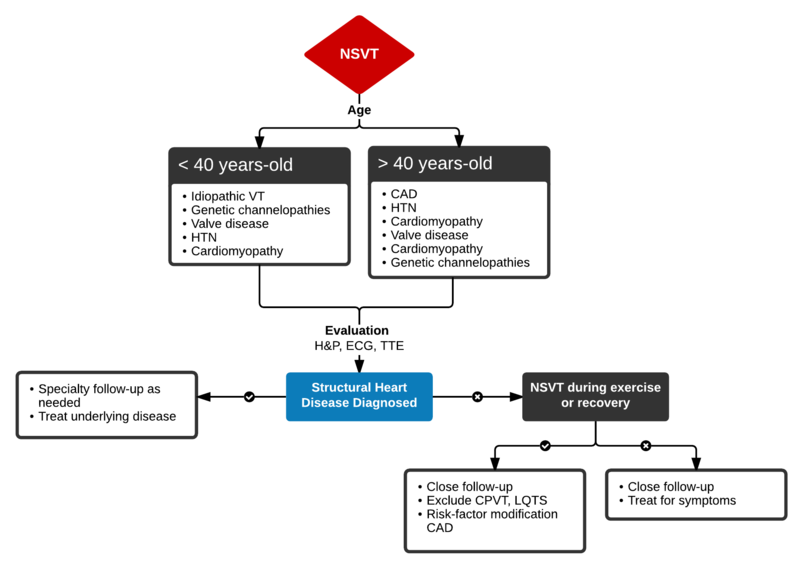

Algorithm for the Evaluation and Management of NSVT

AHA Guidelines[6]

- Nonsustained Repetitive Monomorphic VT: amiodarone, beta-blockade (if tolerated), procainamide (IIA, C)

- Nonsustained Polymorphic VT: Cardioversion for hemodynamic compromise (I, B), B-blockade (I, B), amiodarone if no LQTS (I, C), urgent angiography if ischemia not excluded (I, C)

- Correction of electrolyte abnormalities (specifically hypokalemia) may decrease progression to VF.[7]

Disposition

High-risk patients (age > 45yo, symptomatic, or with known structural heart disease) warrant immediate and appropriate evaluation. This includes echocardiography to identify underlying structural heart disease, exercise testing to evaluate whether NSVT represents underlying ischemic heart disease, and specialized testing in selected patients (ex. EPS, genetic testing in young symptomatic patients, or those with concerning family histories).

See Also

External Links

References

- ↑ Katritsis DG, Zareba W, Camm AJ. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(20):1993–2004. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.063.

- ↑ Wellens HJ. Electrophysiology: Ventricular tachycardia: diagnosis of broad QRS complex tachycardia. Heart. 2001;86(5):579–585.

- ↑ Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(25):1882–1890. doi:10.1056/NEJM199912163412503.

- ↑ Jouven X, Zureik M, Desnos M, Courbon D, Ducimetière P. Long-term outcome in asymptomatic men with exercise-induced premature ventricular depolarizations. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(12):826–833. doi:10.1056/NEJM200009213431201.

- ↑ Udall JA, Ellestad MH. Predictive implications of ventricular premature contractions associated with treadmill stress testing. Circulation. 1977;56(6):985–989.

- ↑ Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death--executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death) Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(17):2099–2140. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl199.

- ↑ Higham PD, Adams PC, Murray A, Campbell RW. Plasma potassium, serum magnesium and ventricular fibrillation: a prospective study. Q J Med. 1993;86(9):609–617.

Authors

Tom Fadial, Daniel Eggeman, Ross Donaldson, Neil Young, Claire, Daniel Ostermayer