Filoviridae

Filoviruses belong to a virus family called Filoviridae and can cause severe hemorrhagic fever in humans and nonhuman primates. So far, only two members of this virus family have been identified: Marburgvirus and Ebolavirus. Five species of Ebolavirus have been identified: Taï Forest (formerly Ivory Coast), Sudan, Zaire, Reston and Bundibugyo. Ebola-Reston is the only known Filovirus that does not cause severe disease in humans; however, it can still be fatal in monkeys and it has been recently recovered from infected swine in South-east Asia.

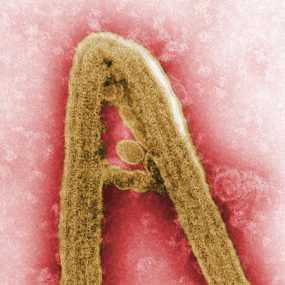

Structurally, filovirus virions (complete viral particles) may appear in several shapes, a biological features called pleomorphism. These shapes include long, sometimes branched filaments, as well as shorter filaments shaped like a “6”, a “U”, or a circle. Viral filaments may measure up to 14,000 nanometers in length, have a uniform diameter of 80 nanometers, and are enveloped in a lipid (fatty) membrane. Each virion contains one molecule of single-stranded, negative-sense RNA. New viral particles are created by budding from the surface of their hosts’ cells; however, filovirus replication strategies are not completely understood.

Filovirus history

The first Filovirus was recognized in 1967 when a number of laboratory workers in Germany and Yugoslavia, who were handling tissues from green monkeys, developed hemorrhagic fever. A total of 31 cases and 7 deaths were associated with these outbreaks. The virus was named after Marburg, Germany, the site of one of the outbreaks. In addition to the 31 reported cases, an additional primary case was retrospectively serologically diagnosed.

After this initial outbreak, the virus disappeared. It did not reemerge until 1975, when a traveler, most likely exposed in Zimbabwe, became ill in Johannesburg, South Africa. The virus was transmitted there to his traveling companion and a nurse. A few sporadic cases and 2 large epidemics (Democratic Republic of Congo in 1999 and Angola in 2005) of Marburg hemorrhagic fever (Margurg HF) have been identified since that time. For information on known Marburg HF cases and outbreaks, please refer to the chronological list.

Ebolavirus was first identified in 1976 when two outbreaks of Ebola hemorrhagic fever (Ebola HF) occurred in northern Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and southern Sudan. The outbreaks involved what eventually proved to be two different species of Ebola virus; both were named after the nations in which they were discovered. Both viruses showed themselves to be highly lethal, as 90% of the Zairian cases and 50% of the Sudanese cases resulted in death.

Since 1976, Ebolavirus have appeared sporadically in Africa, with small to midsize outbreaks confirmed between 1976 and 1979. Large epidemics of Ebola HF occurred in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of Congo in 1995, in Gulu, Uganda in 2000, in Bundibugyo, Uganda in 2008, and in Issiro, DRC in 2012. Smaller outbreaks were identified in Gabon, DRC, and Uganda. For information on known Ebola HF cases and outbreaks, please refer to the chronological list.

Animal hosts

It appears that Filoviruses are zoonotic, that is, transmitted to humans from ongoing life cycles in animals other than humans. Despite numerous attempts to locate the natural reservoir or reservoirs of Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus species, their origins were undetermined until recently when Marburgvirus and Ebolavirus were detected in fruit bats in Africa. Marburgvirus has been isolated in several occasions from Rousettus bats in Uganda.

Spreading Filovirus infections

In an outbreak or isolated case among humans, just how the virus is transmitted from the natural reservoir to a human is unknown. Once a human is infected, however, person-to-person transmission is the means by which further infections occur. Specifically, transmission involves close personal contact between an infected individual or their body fluids, and another person. During recorded outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever caused by a Filovirus infection, persons who cared for (fed, washed, medicated) or worked very closely with infected individuals were especially at risk of becoming infected themselves. Nosocomial (hospital) transmission through contact with infected body fluids – via reuse of unsterilized syringes, needles, or other medical equipment contaminated with these fluids – has also been an important factor in the spread of disease. When close contact between uninfected and infected persons is minimized, the number of new Filovirus infections in humans usually declines. Although in the laboratory the viruses display some capability of infection through small-particle aerosols, airborne spread among humans has not been clearly demonstrated.

During outbreaks, isolation of patients and use of protective clothing and disinfection procedures (together called viral hemorrhagic fever isolation precautions or barrier nursing) has been sufficient to interrupt further transmission of Marburgvirus or Ebolavirus, and thus to control and end the outbreak. Because there is no known effective treatment for the hemorrhagic fevers caused by Filoviruses, transmission prevention through application of viral hemorrhagic fever isolation precautions is currently the centerpiece of Filovirus control.

In conjunction with the World Health Organization (WHO), CDC has developed practical, hospital-based guidelines, titled Infection Control for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers in the African Health Care Setting. The manual can help healthcare facilities recognize cases and prevent further hospital-based disease transmission using locally available materials and few financial resources.

- Page last reviewed: June 18, 2013

- Page last updated: April 7, 2014

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir