4 Internet Partner Services (IPS) Components

There are several features that are important to consider when developing an IPS program, such as adapting patient interviews to include questions about online sex partners, creating profiles, developing email language, and understanding how to confidentially notify partners through the various mediums. These features will be described in this toolkit.

See Appendix A for an example of an IPS program checklist.

4.1 CREATING PROFILES, SCREEN NAMES, AND E-MAIL ADDRESSES

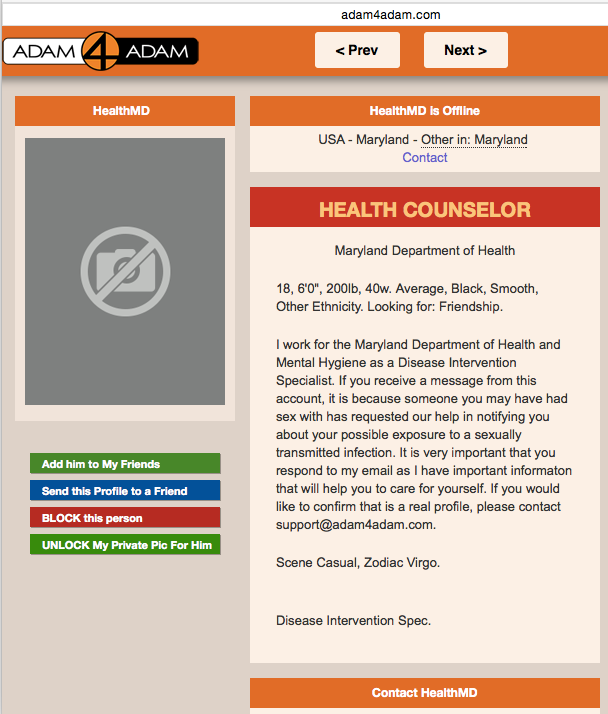

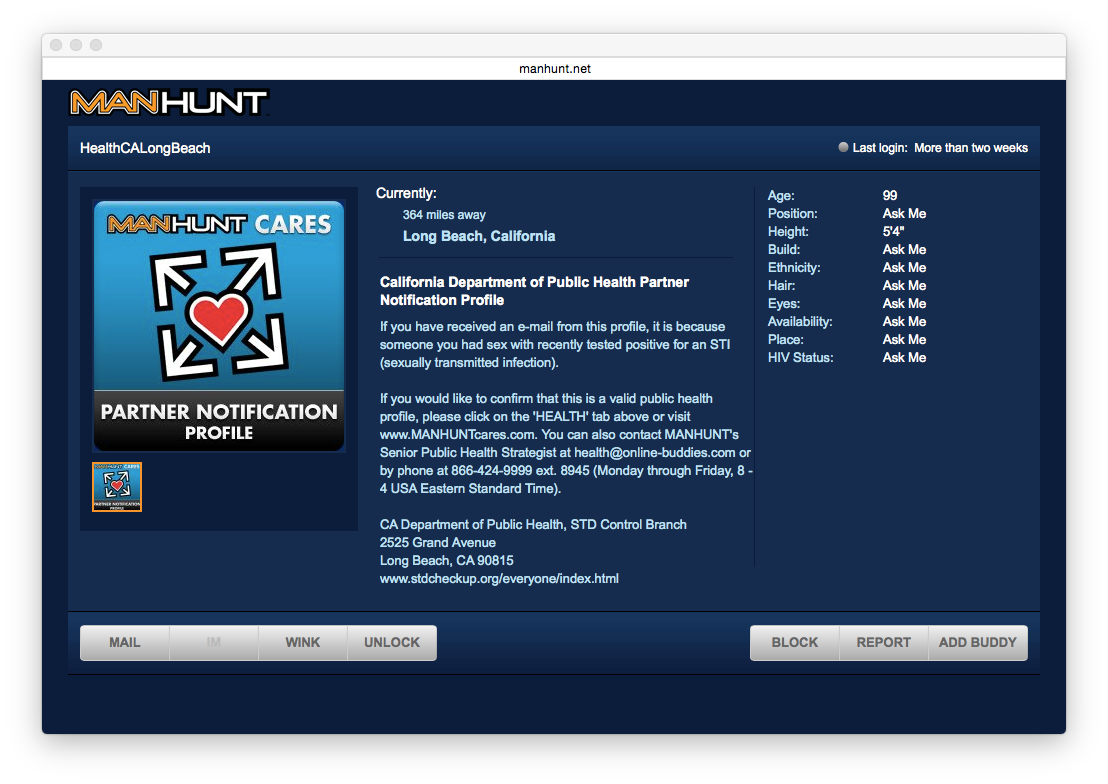

In order access many of the online applications to conduct IPS, programs may need to create a user or member profile. When creating a profile, it is suggested that an official health department email should be associated with the profile, the official health department logo should be used as the account picture, and other identifying information should be provided respective to ISP/website protocol for health departments. Several sites will not allow logos and the profile picture must be of a person. Some profile fields are required for membership but may not be applicable. These could include age, sexual positions, etc. Lastly, some websites may require certain scripted information be contained within your profile. For example, one popular website created a standard logo for all profiles conducting IPS or outreach in order to provide a validation of legitimate IPS-related profiles.

Example from BarebackRt.com, San Francisco Department of Public Health

Example from Adam4Adam.com, Maryland Department of Health

Example from Manhunt.com, California Department of Public Health

It is recommended that before a profile is initiated, a complete review of all “Terms of Services” (TOS) and membership rules be understood.

4.2 INTERVIEWING AND ELICITATION

4.2.1 IPS-specific parts of the original interview

The CDC’s Program Operation Guidelines states: “While interviewing the patient, the DIS should make every attempt to enlist the patient as a resource, making it clear that the information the patient provides will be confidential and very helpful to the DIS, the patient, and the patient’s partners. The DIS can incorporate elements of patient-centered counseling by acknowledging and treating the patient as a partner in reducing additional STDs in their community. The partnership should be clear to the patient.”34

| Programs that are new to IPS often have concerns regarding patient confidentiality and the use of email for IPN. One concern is that sending an email, especially from an organization that uses the acronym ‘STD’ in their email address may unwittingly breach confidentiality if anyone other than the intended recipient views all or part of the email. It is important to note that sending an email carries similar risks to leaving a letter on a doorstep or a voicemail message on a telephone. |

IPS-related questions should be asked in all interviews, whether the patient specifically mentions online venues/apps or not. Until the original patient (OP) indicates otherwise, it can be assumed that the OP has met or communicated with at least some of their sex partners through virtual or technology-based media. When interviewing patients, DIS can ask about sex partners met through online networking by using open-ended questions and specifically naming known websites used for sex-seeking. This helps to let the patient know that the DIS is familiar with and comfortable discussing such venues. See Appendix B for examples of IPS-related questions to ask during interviews.

|

Example of an opened ended versus a yes/no question Open ended – What is your profile name on [insert name of website]? Yes/no question – Do you use [insert name of website?] |

At a minimum, it is important that DIS attempt to obtain OP screen names and associated venue (website, mobile app), email addresses and verify physical locating information. This information will be useful if a partner references the OP in an interview. Furthermore, in future cases, if the OP’s screen name is named as a partner, locating information will already exist in the database, and PN can be initiated. It is equally important for DIS to gather and confirm the exact spelling of partner screen names, email addresses and physical locating information. Confirming the exact spelling is extremely important because often numbers and characters are used in lieu of letters i.e. Man4you vs. Manforu. However, it is important to remember that all information provided within a profile is subject to change and that the profile itself can be deleted at any time. Lastly, DIS can ask about physical locations where sexual encounters took place such as a person’s home or hotel. This information can help give an approximate geographic location of a partner.

4.2.2 Access to internet/mobile devices during the interview

Having computers and mobile devices that can access the internet available during the interview can improve the information obtained during an interview. Having access to named websites allows the OP or the DIS to immediately log on to that site to access and verify information about sex partners and can lead to an increase in the number of partners named. Notification emails can also be sent to all sex partners at the time of the interview either through the program’s profile or from the OP.

4.2.3 Geographic location of a partner

Prior to initiating IPN, it is important to attempt to obtain and confirm the geographic location of the individual being contacted. Knowing the geographic location of the sex partner will allow the DIS to confirm whether the client resides within the DIS’s jurisdiction and provide appropriate referral information (i.e., clinic locations, clinic times). The physical location of a website member is often listed within the individual’s online profile. However, the true physical location of a partner may not be known until contact is made, due to the ability to change location within many online and mobile sites. Thus, the location of a profile at any given time may not actually reflect the user’s residency, but instead may indicate that the partner is “surfing” the site for members in that particular geographic area.

4.2.4 Out of Jurisdiction (OOJ) Issues

Email addresses and screen names with an identified geographic location outside of a program’s jurisdiction may require that an “out of jurisdiction” (OOJ) field record be initiated. It is important to discuss the situation with the appropriate program in the jurisdiction in which the partner is believed to reside to understand that jurisdiction’s protocols for handling Internet locating information and IPN. If there are not established standards of practice for handling OOJ, these situations will need to be handled on a case-by-case basis.

4.3 LANGUAGE USED FOR TECHNOLOGY-BASED PARTNER NOTIFICATION

The language used for partner notification varies, depending on several factors, including the specific person you are contacting, the venue (e.g., email versus a website versus text) through which you are attempting to contact a person, the type of infection that the person has been exposed to, and state and local regulations on what can be disclosed in what medium. IPS works best when protocols, guidelines, handbooks, and manuals allow for notification language to be adjusted based on these factors.

|

The language you use for partner notification is important and depends on these factors:

|

Legitimacy of the notification is enhanced when the following information is included: name of the contacting DIS, program or health department affiliation, contact information, and a brief message encouraging the partner to contact the DIS as soon as possible. Other information can be included, space permitting, such as times the DIS can be reached in the office, frequency with which emails, voicemails, etc. are checked, how the patient can confirm the DIS’s identity, such as the name of a supervisor and his/her telephone number, and the case referral number. It may also be helpful to mention that leaving a message on voicemail is confidential, if this is indeed the case. Some programs require all outgoing emails to have a legal disclaimer. Programs can discuss the language used, and if a legal disclaimer is necessary, with their legal department. Below are a few examples of legal disclaimers

|

At a minimum, it is important all notification messages include the following information:

|

Sending notifications from and to official health department email addresses or profiles also helps to legitimize the notification for the recipient. Partner notification from personal email addresses or digital profiles is discouraged. Whenever possible, messages should be accompanied by an automatic request for notification when the message is read.

4.3.1 Language specificity

Patient characteristics (e.g., adolescent versus adult) and the venue through which you are trying to reach a patient will determine the type of language you use. Care and consideration should be given to both the person you are attempting to reach and the medium through which you are trying to reach them when deciding what type of language to use when sending a message. Programs typically err on the side of caution and use the most conservative or vague language when there is any concern about potentially breeching confidentiality. See Appendix C for additional examples of initial IPN emails.

4.3.2 "Urgent health matter”

For text messages, which can be seen by others and for certain social networking sites, like Facebook, where accounts are shared with friends or monitored by parents, broad or generic language such as “urgent health matter” is suggested. Instant messaging is not recommended for partner notification but in cases where it is used, broad or generic language should be employed.

|

Example 1: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Bureau of STD Control Dear <<screenname>> ***This email is intentionally vague in order to protect your privacy.** I am contacting you about an urgent health matter. It is most important that you report to the _______________ Health Center located at _________________. Please print a copy of this email and bring it with you as it can reduce your waiting time. If you are unable to bring a copy of the email please let the health center staff know that you were contacted by me and asked to visit the clinic. If you have any questions regarding this notice, please feel free to contact me at (212) 788-6619 Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 4:00p.m. Services at the health center are free and confidential. If you prefer to consult a private physician please ask him or her to contact me for information on the health matter I am contacting you about. If I am not available at the time of your call please leave a number and time when I can reach you. My voicemail is private, confidential, and password-protected. This email is intentionally vague in order to protect your privacy. Please visit the health center or contact me by telephone for more information. Sincerely, DIS NAME NYC Department of Health & Mental Hygiene DIS EMAIL |

4.3.3 “Exposure to an infectious disease”

Sexual networking sites and certain email addresses, such as those found on dating sites, are more amenable to language that indicates exposure to an unknown infection such as “you may have been exposed to an infectious disease.”

4.3.4 “Exposure to a specific disease”

Lastly, some of the sexual networking sites require the use of disease specific language when reaching out to their members for partner notification e.g., “someone you may have had sex with tested positive for syphilis.” It is important to review the Terms of Services (TOS) and determine what acceptable actions are allowed.

|

Example 3: Tennessee Department of Health To: <screen name/email address> From: Name@tn.gov Subject: (leave blank) Hello <name, if known>, (do not use screen name) A few days ago, I sent you an email, but I have not heard back from you. My name is ____ and I work for the Tennessee Department of Health. I am contacting you because someone who was recently diagnosed with laboratory confirmed <gonorrhea, Chlamydia, syphilis> asked that you be notified of an exposure to this infection. It is important that you call me at __________ so I can speak with you confidentially about the specific exposure and provide you with options for testing and treatment. To confirm this email is authentic and legitimate, you can call my supervisor ________ at ####. [If using Manhunt to conduct notification include: *If you would like to confirm that this email is real though Manhunt, please call the Manhunt Health Liaison at 617-674-8945. If using Adam4Adam include: “If you would like to confirm that this email is real though Adam4Adam please contact support@adam4adam.com”] Thank you for your prompt response. DIS name DIS title Phone # |

To date, no formal studies have been conducted to determine the most effective means of getting a contacted partner to respond to a DIS, however, anecdotal evidence from experienced programs has found that including specific disease information in proprietary email systems is safe and acceptable to the recipients. In general, proprietary systems are password-protected, and members of websites with proprietary email systems typically have individual accounts. If members choose to share an account with another person, it is typically because they are in a relationship and looking for group sexual encounters.

Because of the unique issues found within online communities, the emails you send to contacts may at first be perceived as “spam” (unsolicited email) or a hoax. To encourage patients to read email and avoid appearing as “spam,” some programs leave the subject field blank, containing no text. Other programs have standard subject lines such as “Confidential message from the (insert local health department name),” or, “Please call the (insert local health department name).” If emails aren’t being read, new subject lines and methods can be considered.

Subsequent attempts to contact the partner may include, where appropriate, additional information to increase the sense of urgency, request the individual’s consent to receive information via another medium, such as a private email address, or provide disease-specific exposure information.

Programs will need to determine the allowable number of times a patient may be contacted. Experienced programs recommend no more than three attempts to initiate contact with the patient. Some websites have policies regarding the number of times a health department or CBO may contact their members, with most limiting it to a maximum of three attempts. It is important to remember that each situation may require different strategies.

See below and Appendix D for additional examples of follow up emails

|

To: <screen name/email address> From: Name@tn.gov Subject: (leave blank) Hello <name, if known>, (do not use screen name) A few days ago, I sent you an email, but I have not heard back from you. It is important that you call me at __________ so I can speak with you confidentially about the specific exposure and provide you with options for testing and treatment. To confirm this email is authentic and legitimate, you can call my supervisor ________ at ####. [If using Manhunt to conduct notification include: *If you would like to confirm that this email is real though Manhunt, please call the Manhunt Health Liaison at 617-674-8945. If using Adam4Adam include: “If you would like to confirm that this email is real though Adam4Adam please contact support@adam4adam.com”]

|

4.4 CONFIDENTIALITY DURING PARTNER NOTIFICATION/PARTNER SERVICES

4.4.1 Reaching the right person

It’s very important to ensure that all emails and messages are sent to the intended recipients. Locating online partners has become much more challenging due to the variable ease and frequency with which email addresses, screen names, and IM and smartphone app accounts can be obtained and changed. Screen names may be very similar and sound the same. For example, members with the screen names “partyboi” or “Man4U” are likely different users than members with the screen names “partyboy” or “Manforyou.” When feasible, have the OP access email messages, SMS profiles and saved instant messages to confirm the spelling of partners’ screen names during the original interview. Be sure that the OP has logged completely out of their account when done. Additionally, eliciting descriptive details about partners, such as race, height, weight, interests, location, and other identifying characteristics, can help DIS verify that the correct person is being contacted. The experience reported by many STD programs is that patient confidentiality can be maintained in the same way that confidentiality is maintained when conducting PN via the telephone.

It is important to acknowledge that the individuals we are attempting to contact could share an email account or profile with another person. However, anecdotally, experienced programs have found that the vast majority of email addresses and profiles reported are not shared. Profile names that indicate that a profile may be shared by two or more people (e.g. “2hotmen) should be closely reviewed before sending information. If there is evidence that an email or profile is shared, or any level of uncertainty exists, then information should not be sent and should be discussed with a Supervisor.

4.4.2 Protecting confidentiality

In some cases, the use of individual identifiers (screen names, email addresses, profile names, etc.) combined with language that specifically mentions exposure to a specific infection, such as HIV, may be interpreted as a confidentiality breach. As mentioned earlier, certain venues may be less secure than others. For example, contacting a minor through Facebook using language such as “someone you had sex with was recently diagnosed with an infectious disease” may be a breach of confidentiality, as many parents monitor their child’s Facebook account. However, when contacting the same individual through an online sex-seeking venue, where his or her account would most likely not be known or monitored by a parent, using the same language may be appropriate. Some barriers related to confidentiality and messaging can be avoided by using broad or generic messaging that omits any mention of sexual activity. Examples of broad or generic messaging include “potential exposure to an infection” and “urgent health matter”.

|

Be aware that different websites have different options that may help maintain or potentially breach confidentiality. For example, when creating a profile on certain sex-seeking websites, the default settings include a function that allows all users to see who has visited a profile. Unless that functionality is turned off in the “Accounts Options” section, all users will be able to see that a health department virtually visited a member’s profile. This can lead to breaches in confidentiality or distrust of health department activities. |

Some health departments have found IPS to be more successful when the OP makes first contact with named partners, with follow-up by DIS, versus first contact by DIS.

DIS can provide support and guidance to the OP about how to notify their sex partners, including what language to use, provide resources, such as testing sites, or provide an example email. Patient-initiated IPN messages should include the name and contact information of the DIS.

When the OP makes first contact with a potentially-infected partner, there are generally three ways in which contact can occur:

The OP contacts their partner(s) directly, on their own initiative, notifying partners of their potential exposure and indicating that DIS will be reaching out to the partner for STD screening and partner services. Afterwards, the OP will follow up with the DIS on whether or not partners were contacted.

OPs can also notify their partners in the presence of DIS by contacting partners through health department computers or phones, or by using their own digital devices (e.g., mobile phone). This method provides evidence that partners were, indeed, contacted and notified.

Lastly, OPs can use third-party sites, which allow them to contact and notify partners anonymously. There are limited outcome evaluation data available on these third-party notification sites, and there is potential for false or “joke” notifications. These sites may have the potential to improve PS for STDs such as chlamydia and gonorrhea, which often do not fall within the purview of PS. However, for STDs such as HIV and syphilis, the DIS model is still recommended because there is no way of verifying that a partner was actually notified, or that the individual sending the notification even has a laboratory-confirmed STD.

When a partner calls or comes to the clinic, it is important to ask how the partner was notified of a potential exposure. If the individual was notified via IPS, the DIS may not have the real name of the individual. DIS should ask the individual for the referral letter or number or his/her Internet screen name or e-mail address, then search the case management data system (e.g., STD*MIS). Once the DIS confirms the identity of the individual through other identifying information obtained from the original patient, the field record needs to be updated. It is important to retain the IPS information such as the screen name and website; not delete the screen name or website from the AKA section.

4.5 TEXT NOTIFICATION & MOBILE APPLICATIONS

Mobile technologies (smart phones, tablets, cell phones, etc.) are changing the way in which we contact people, including how we conduct partner notification. Mobile phones and sex-seeking mobile applications (apps), in particular, have become increasingly relevant to STD prevention and partner notification.

In the U.S., 90% of adults (persons 18 years and older) have a cell phone7 and, often, a cell phone may be the only form of contact information available for a partner. Increasingly, cell phones are replacing landline telephones. A report released in June 2015 by the CDC found that more than two of every five American homes, or 45%, did not have landline telephones but did have at least one wireless phone.35 Additionally, cell phones are used for much more than making phone calls. Eighty one percent of cell phone users send and receive cell phone texts, 60% of cell phone users use their phones to access the Internet, and 52% use their phones for email.36 Currently, 64% of U.S. adults own a smart phone,7 which allows quick and easy access to social and sexual networking sites.

Little is known about the use of sex-seeking mobile apps and their impact on STDs. Popular mobile apps such as Grindr and Tinder self-report 5 million (www.grindr.com) and 10 million (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinder) users respectively. Current knowledge about the sex-seeking apps has primarily focused on those apps that cater to gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Two studies found that users of gay, sex-seeking, mobile apps are more likely to be younger, to be white or Asian, and to report more sex partners.37,38 In the Beymer et al. study, sex-seeking app users also had a greater proportion of gonorrhea and chlamydia, but a lower proportion of HIV, when compared to those who meet sex partners either in-person or online. In terms of sexual risk, these two studies looked at unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) among sex-seeking mobile app users and found a range of 14.7% to 46% of users engaged in UAI.16,19

| 95% of young men who have sex with men and use Grindr also report using Facebook.14 This suggests that users of sex-seeking mobile apps may also be locatable on other social networking sites. |

Because of the popularity of cell phones and mobile apps and because, in some cases, it is the only means of reaching a person, health departments are now using text messaging protocols for partner notification and exploring how to conduct PN through mobile apps.

4.5.1 Using Text Messaging/Short Message Service (SMS) for Partner Notification

Some health departments have implemented text messaging as part of the standard efforts to notify a partner of their exposure. For example, if a cell phone number is known, then a text message is sent in conjunction with other notification efforts. Other programs resort to text messaging only when other notification efforts have failed. Regardless of when texting is used, the goal of texting is to get the patient to call the DIS. Multnomah County has found that 67% of clients return a phone call immediately after receiving an IPS text (personal correspondence, J. Mendez, August 15, 2014). In 2012, Multnomah County began using Google Voice to send texts, which allows DIS to send, receive and store free text messages. See Appendix E for examples of text messaging policies for partner services including a copy of the Multnomah Guidance on using Google Voice for sending texts for partner services. Programs have found texting to improve outcomes, reach people for whom other notification efforts were unsuccessful and to reduce the need for mailing letters or making field visits. 15,30-32

| Many smart phone users can receive text messages even if the phone is not accepting phone calls, i.e., they run out of minutes. |

4.5.2 Confidentiality and risks of text messaging

Maintaining patient confidentiality is of the utmost importance when using texts for partner notification. Text messages carry similar risks as other forms of partner notification. Just like a letter or voice mail message that can be read or listened to by someone other than the intended recipient, text messages can also be sent to or read by others. It is important to remember that text messages can be copied, forwarded to others, altered or stored electronically without authorization or detection. Programs can minimize these risks by taking the following suggested precautions.

- Broad partner notification language should be used, i.e., “important health matter.” Sending disease specific information via text message is not recommended. (See Appendix E for examples of acceptable PN texting language.)

- Text messages should only be sent from a work phone or computer. We do not recommend the use of personal cell phones or computers when communicating with clients or their partner(s).

- All mobile devices should be password protected

- Text messages should be sent from a private space

- Some cell phone carriers will provide you with an option to receive a text message delivery confirmation. This service, where available, is requested by you through the settings on your cellular phone or through your carrier account preferences.

A concerted effort should be made to ensure that the correct telephone number is being use for contact. This can be done by confirming the contact number with the number on file or by using Internet tools such as reverse search tools to confirm the number is connected to a mobile device. Example: http://www.phonelookup.com – at the time of this writing, this website could reveal whether a number was a cell or landline phone number and the general location, but it does not provide names or street addresses. It is important to note that information obtained through a reverse lookup may not be the most current information. It is also possible for a cell phone subscriber to retain a cell phone number that has been assigned by one carrier when switching to a new cellular provider. In this case the previous cellular provider may be inaccurately listed as the current provider.

|

To search for a telephone number using Google In the Google search box, type allintext (all one word), followed by a colon, followed by the number you are searching for in quotations. Example - allintext: “555-555-5555” |

4.5.3 Communication etiquette

Understanding and using mobile device etiquette is important and can help improve response rates from patients and/or their partners. Following are some helpful tips.

- Be professional at all times. Avoid the use of abbreviations, jargon, acronyms, or images.

- Be timely in your response to returned texts. Returned texts can come at any time of the day. Be prepared to respond within a reasonable time frame.

- Recognize that it is extremely difficult to discern tone in text messages. It is very hard to discern humor, sarcasm, etc. from a text.

- Know that some users may not have a text messaging plan and that each incoming and outgoing text may cost them money

- Texts may be limited in character count. For example, a text message over 160 characters may be split into two messages.

- If, after making contact with a patient or partner, you would like to text to confirm an appointment or meeting time, it is important to obtain the person’s permission.

4.5.4 Mobile applications (apps)

Sex-seeking, mobile apps come with a unique set of issues that can make notifying a partner challenging. Mobile apps are developed to increase the speed and efficiency of meeting potential partners through the use of the global positioning system (GPS) functionality of many mobile phones. By using GPS, mobile apps are able to locate users in space and provide that information to other users who are within a designated radius. What potential partners of a mobile app user will see depends on where they are physically located at the specific moment they are using the app. When a person closes the app or is outside the designated radius, their profile is often not seen. This geographic specificity creates challenges for PN.

4.5.5 Current challenges

DIS face a number of challenges when attempting to reach a partner for whom only mobile app information is known. Presently, we know of no mobile apps that have officially sanctioned the use of their apps for partner services purposes. The few programs who are attempting to use mobile apps for partner services have done so without expressed permission and many of these program profiles have been blocked by the managers of the app. Additionally, few DIS have access to mobile applications either for information gathering or for partner notification purposes. A recent assessment of STD programs and IPS activities indicated that 71% of individuals responding reported not being able to use mobile apps for PN, and 61% were not able to use mobile apps for information gathering. Lack of access can be a result of local policies, a lack of training and/or not having access to the necessary equipment (smart phone). Even with access, however, reaching an identified partner can be challenging because of the app’s design and because of GPS functionality. Many of the mobile apps do not require unique profile names. As a result, there may be multiple profiles with the same profile name (e.g. James), making it difficult to ascertain if you are reaching the intended person. Additionally, many of the apps do not have a search function, so even in the event of a unique profile name, there may not be a way to search the entire mobile app for that user. Lastly, GPS functionality creates an additional barrier to finding a particular person, since that person has to be both actively using the app and be within the required radius in order for his or her profile to appear on the app.

To overcome some of these challenges, some programs have focused on working with the OP to access and gather information using the OP’s mobile app profile. DIS can ask the OP to log onto the mobile app during the interview and look in certain sections of the app for pertinent information. For example, most sex-seeking mobile apps contain certain functions, such as an internal messaging system and a way of “favoriting” people that is, marking them so that they can be easily retrieved. The OP can look at his internal messages and his favorites list to help name, identify, and reach partners. In the event of a unique profile name, the search function can be used, if available. Some DIS will search for a specific username in the physical vicinity where the sexual contact between the OP and the partner was made.

While it is not necessary for the DIS to look at an OP’s mobile phone and/or mobile app profiles, doing so can be extremely helpful when gathering and verifying partner information.

4.5.6 Tips for gathering information on mobile app profiles

Similar to going onto a sex-seeking website with a patient, accessing a patient’s mobile app profile during an interview can help to confirm the spelling of profile names, provide physical descriptions and pictures, and obtain information forgotten by the patient. Asking the patient to check sent folders, trash folders, and “favorites” can yield additional locating information such as cell phone numbers, physical addresses, and profile names of additional sex partners. It is important to remember that a mobile app profile is a marketing tool to attract sex partners and may contain fantasy or be written in a specific way. Allowing someone else to view a sex-seeking profile can make the patient feel vulnerable and subject to judgment. It is important to practice respect and emphasize confidentiality when a patient provides DIS access to their profiles. If a patient is unwilling to access their mobile app profiles in the presence of the DIS, DIS should encourage the patient to email or call with a list of partners and relevant partner information. It is important to emphasize confidentiality and the need to be timely in providing the information.

- Page last reviewed: January 20, 2016

- Page last updated: January 20, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir