US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use

Introduction

On This Page

- Methods

- How to Use This Document

- Keeping Guidance Up to Date

- Acknowledgements

- References

- BOX 1. Categories of medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use

- BOX 2. Conditions associated with increased risk for adverse health events as a result of unintended pregnancy

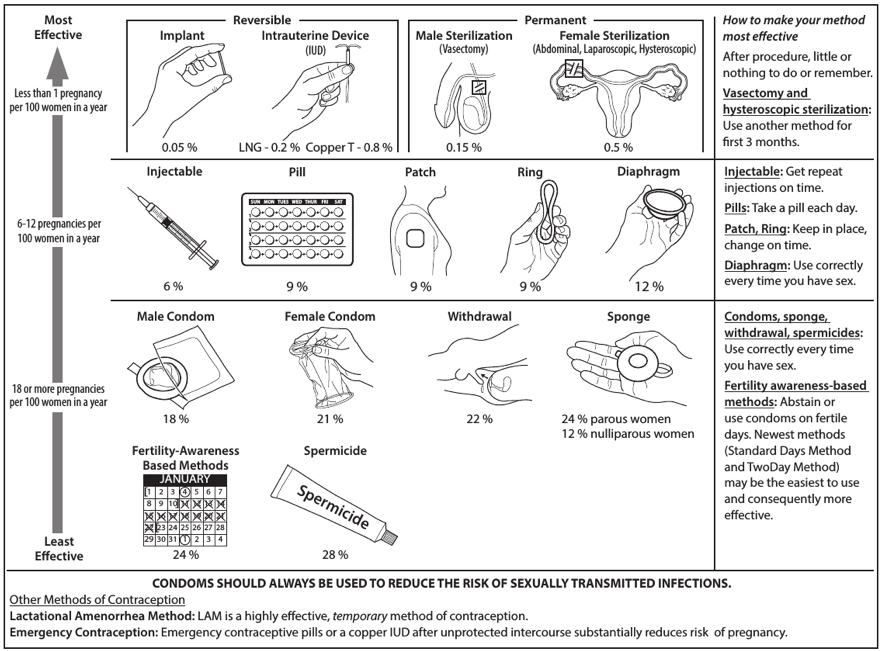

- FIGURE. Effectiveness of family planning methods

Approximately 45% of all pregnancies that occur in the United States are unintended (1), with associated increased risks for adverse maternal and infant health outcomes (2) and increased health care costs (3). Women, men, and couples have increasing numbers of safe and effective choices for contraceptive methods, including long-acting reversible contraception methods such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants, to reduce the risk for an unintended pregnancy. However, with these expanded options comes the need for evidence-based guidance to help health care providers offer quality family planning care to their patients, including choosing the most appropriate contraceptive method for individual circumstances and using that method correctly, consistently, and continuously to maximize effectiveness.

In 2010, CDC published the first U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (U.S. MEC), which provided recommendations on safe use of contraceptive methods for women with various medical conditions and other characteristics (and was adapted from global guidance developed by the World Health Organization [WHO MEC]) (4,5). U.S. MEC is a companion document to the U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (U.S. SPR), which provides guidance on how to use contraceptive methods safely and effectively once they are deemed to be medically appropriate (6). WHO intended for the global guidance to be used by local or national policy makers, family planning program managers, and the scientific community as a reference when they develop family planning guidance at the country or program level. During 2008–2010, CDC participated in a formal process to adapt the global guidance for appropriateness for use in the United States, which included rigorous identification and critical appraisal of the scientific evidence through systematic reviews, and input from national experts on how to translate that evidence into recommendations for U.S. health care providers (5). At that time, CDC committed to keeping this guidance up to date and based on the best available evidence, with full review every few years (5).

This document updates CDC’s U.S. MEC 2010 (5), based on new evidence and input from experts. A summary of changes from U.S. MEC 2010 is provided. Notable updates include the following:

- addition of recommendations for women with cystic fibrosis, women with multiple sclerosis, and women receiving certain psychotropic drugs or St. John’s wort

- revisions to the recommendations for emergency contraception, including the addition of ulipristal acetate

- revisions to the recommendations for postpartum women; women who are breastfeeding; women with known dyslipidemias, migraine headaches, superficial venous disease, gestational trophoblastic disease, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); and women who are receiving antiretroviral therapy

The goal of these recommendations is to remove unnecessary medical barriers to accessing and using contraception, thereby decreasing the number of unintended pregnancies. These recommendations are meant to serve as a source of clinical guidance for health care providers; health care providers should always consider the individual clinical circumstances of each person seeking family planning services. This report is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice for individual patients, who should seek advice from their health care providers when considering family planning options.

Methods

Since publication of U.S. MEC 2010, CDC has monitored the literature for new evidence relevant to the recommendations through the WHO/CDC continuous identification of research evidence (CIRE) system. This system identifies new evidence as it is published and allows WHO and CDC to update systematic reviews and facilitate updates to recommendations as new evidence warrants. Automated searches are run in PubMed weekly, and the results are reviewed. Abstracts that meet specific criteria are added to the web-based CIRE system, which facilitates coordination and peer review of systematic reviews for both WHO and CDC (7). In 2014, CDC reviewed all of the existing recommendations in U.S. MEC 2010 for new evidence identified by CIRE that had the potential to lead to a changed recommendation. During August 27–28, 2014, CDC held a meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, of 11 family planning experts and representatives from partner organizations to solicit their input on the scope of and process for updating both U.S. MEC 2010 and U.S. SPR 2013. The participants were experts in family planning and represented various types of health care providers, as well as health care provider organizations. A list of participants is provided at the end of this report. Meeting participants discussed topics to be addressed in the update of U.S. MEC based on new evidence published since 2010 (identified through the CIRE system), topics addressed at a 2014 WHO meeting to update global guidance, and suggestions CDC received from health care providers for the addition of recommendations for women with medical conditions not yet included in U.S. MEC (e.g., from provider feedback through e-mail, public inquiry, and questions received at conferences). CDC identified several topics to consider when updating the guidance, including revision of existing recommendations for certain medical conditions or characteristics (breastfeeding, postpartum, HIV, receiving antiretroviral therapy, obesity, dyslipidemia, increased risk for STDs, superficial venous thrombosis, gestational trophoblastic disease, and migraine headaches), addition of recommendations for new medical conditions (cystic fibrosis, multiple sclerosis, use of certain psychotropic drugs, and St. John’s wort), and addition of recommendations for new contraceptive methods (ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception). CDC determined that all other recommendations in U.S. MEC 2010 were up to date and consistent with the existing body of evidence for that recommendation.

In preparation for a subsequent expert meeting held during August 26–28, 2015, to review the scientific evidence for potential recommendations, CDC staff members and other invited authors listed at the end of this report conducted independent systematic reviews for each of the topics being considered. The purpose of these systematic reviews was to identify direct evidence about the safety of contraceptive method use by women with selected conditions (e.g., risk for disease progression or other adverse health effects in women with multiple sclerosis who use combined hormonal contraceptives [CHCs]). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed for reporting systematic reviews (8,9), and strength and quality of the evidence were assigned using the system of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (10). When direct evidence was limited or not available, indirect evidence (e.g., evidence on surrogate outcomes or among healthy women) and theoretical issues were considered and either added to direct evidence within a systematic review or separately compiled for presentation to the meeting participants. Completed systematic reviews were peer reviewed by two or three experts and then provided to participants before the expert meeting. Reviews are referenced and cited throughout this document; the full reviews appear in the published literature and contain the details of each review, including the systematic review question, literature search protocol, inclusion and exclusion criteria, evidence tables, and quality assessments. CDC staff continued to monitor new evidence identified through the CIRE system during the preparation for the August 2015 meeting.

During August 26–28, 2015, in Atlanta, Georgia, CDC held a meeting with 44 participants who were invited to provide their individual perspectives on the scientific evidence presented and potential recommendations. Twenty-nine of the participants represented a wide range of expertise in family planning provision and research, and included obstetricians/gynecologists, pediatricians, family physicians, nurse practitioners, epidemiologists, and others with research and clinical practice expertise in contraceptive safety, effectiveness, and management; these individuals participated in the entire meeting. Fifteen participants with expertise relevant to specific topics on the meeting agenda provided information and participated in the discussion (e.g., an expert in cystic fibrosis was asked to provide general information about the condition and to assist in interpreting the evidence and any theoretical concerns on the use of contraceptive methods in women with the condition); these participants provided input only during the session for which their topics were discussed. Lists of participants and any potential conflicts of interest are provided at the end of this report. During the meeting, the evidence from the systematic review for each topic was presented, including direct evidence and any indirect evidence or theoretical concerns. Participants provided their perspectives on using the evidence to develop recommendations that would meet the needs of U.S. health care providers. After the meeting, CDC determined the recommendations in this report, taking into consideration the perspectives provided by the meeting participants. Feedback also was received from three external reviewers, composed of health care providers and researchers who had not participated in the update meetings. These reviewers were asked to provide comments on the accuracy, feasibility, and clarity of the recommendations. Areas of research that need additional investigation also were considered during the meeting (11).

How to Use This Document

These recommendations are intended to help health care providers determine the safe use of contraceptive methods among women and men with various characteristics and medical conditions. Providers also can use the information in these recommendations when consulting with women, men, and couples about their selection of contraceptive methods. The tables in this document include recommendations for the use of contraceptive methods by women and men with particular characteristics or medical conditions. Each condition is defined as representing either an individual’s characteristics (e.g., age, or history of pregnancy) or a known preexisting medical/pathologic condition (e.g., diabetes or hypertension). The recommendations refer to contraceptive methods being used for contraceptive purposes; the recommendations do not consider the use of contraceptive methods for treatment of medical conditions because the eligibility criteria in these situations might differ. The conditions affecting eligibility for the use of each contraceptive method are classified into one of four categories (Box 1).

Using the Categories in Practice

Health care providers can use the eligibility categories when assessing the safety of contraceptive method use for women and men with specific medical conditions or characteristics. Category 1 comprises conditions for which no restrictions exist for use of the contraceptive method. Classification of a method/condition as category 2 indicates the method generally can be used, although careful follow-up might be required. For a method/condition classified as category 3, use of that method usually is not recommended unless other more appropriate methods are not available or acceptable. The severity of the condition and the availability, practicality, and acceptability of alternative methods should be considered, and careful follow-up is required. Hence, provision of a contraceptive method to a woman with a condition classified as category 3 requires careful clinical judgement and access to clinical services. Category 4 comprises conditions that represent an unacceptable health risk if the method is used. For example, a smoker aged <35 years generally can use combined oral contraceptives (COCs) (category 2). However, for a woman aged ≥35 years who smokes <15 cigarettes per day, the use of COCs usually is not recommended unless other methods are not available or acceptable to her (category 3). A woman aged ≥35 years who smokes ≥15 cigarettes per day should not use COCs because of unacceptable health risks, primarily the risk for myocardial infarction and stroke (category 4). The programmatic implications of these categories may depend on the circumstances of particular professional or service organizations. For example, in some settings, a category 3 might mean that special consultation is warranted.

The recommendations address medical eligibility criteria for the initiation and continued use of all methods evaluated. The issue of continuation criteria is clinically relevant whenever a medical condition develops or worsens during use of a contraceptive method. When the categories differ for initiation and continuation, these differences are noted in the Initiation and Continuation columns. When initiation and continuation are not indicated, the category is the same for initiation and continuation of use.

On the basis of this classification system, the eligibility criteria for initiating and continuing use of a specific contraceptive method are presented in tables (Appendices A–K). In these tables, the first column indicates the condition. Several conditions are divided into subconditions to differentiate between varying types or severity of the condition. The second column classifies the condition for initiation or continuation (or both) into category 1, 2, 3, or 4. For certain conditions, the numeric classification does not adequately capture the recommendation; in these cases, the third column clarifies the numeric category. These clarifications were determined during the discussions of the scientific evidence and are considered a necessary element of the recommendation. The third column also summarizes the evidence for the recommendation if evidence exists. The recommendations for which no evidence is cited are based on expert opinion from either the WHO or U.S. expert meeting in which these recommendations were developed, and might be based on evidence from sources other than systematic reviews. For certain recommendations, additional comments appear in the third column and generally come from the WHO meeting or the U.S. meeting.

Recommendations for Use of Contraceptive Methods

The classifications for whether women with certain medical conditions or characteristics can use specific contraceptive methods are provided for intrauterine contraception, including the copper-containing IUD and levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs; progestin-only contraceptives (POCs), including etonogestrel implants, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections, and progestin-only pills; CHCs, including low-dose (containing ≤35 μg ethinyl estradiol) COCs, combined hormonal patch, and combined vaginal ring; barrier contraceptive methods, including male and female condoms, spermicides, diaphragm with spermicide, and cervical cap; fertility awareness–based methods; lactational amenorrhea method; coitus interruptus; female and male sterilization; and emergency contraception, including emergency use of the copper-containing IUD and emergency contraceptive pills. A table at the end of this report summarizes the classifications for the hormonal and intrauterine methods.

Contraceptive Method Choice

Many elements need to be considered by women, men, or couples at any given point in their lifetimes when choosing the most appropriate contraceptive method. These elements include safety, effectiveness, availability (including accessibility and affordability), and acceptability. The guidance in this report focuses primarily on the safety of a given contraceptive method for a person with a particular characteristic or medical condition. Therefore, the classification of category 1 means that the method can be used in that circumstance with no restrictions with regard to safety but does not necessarily imply that the method is the best choice for that person; other factors, such as effectiveness, availability, and acceptability, might play a key role in determining the most appropriate choice. Voluntary informed choice of contraceptive methods is an essential guiding principle, and contraceptive counseling, when applicable, might be an important contributor to the successful use of contraceptive methods.

In choosing a method of contraception, dual protection from the simultaneous risk for HIV and other STDs also should be considered. Although hormonal contraceptives and IUDs are highly effective at preventing pregnancy, they do not protect against STDs, including HIV. Consistent and correct use of the male latex condom reduces the risk for HIV infection and other STDs, including chlamydial infection, gonococcal infection, and trichomoniasis (12). Although evidence is limited, use of female condoms can provide protection from acquisition and transmission of STDs (12). All patients, regardless of contraceptive choice, should be counseled about the use of condoms and the risk for STDs, including HIV infection (12). Additional information about prevention and treatment of STDs is available from the CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines (https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment) (12).

Contraceptive Method Effectiveness

Contraceptive method effectiveness is critical for minimizing the risk for an unintended pregnancy, particularly among women for whom an unintended pregnancy would pose additional health risks. The effectiveness of contraceptive methods depends both on the inherent effectiveness of the method itself and on how consistently and correctly it is used (Figure). Methods that depend on consistent and correct use have a wide range of effectiveness. IUDs and implants are considered long-acting, reversible contraception (LARC); these methods are highly effective because they do not depend on regular compliance from the user. LARC methods are appropriate for most women, including adolescents and nulliparous women. All women should be counseled about the full range and effectiveness of contraceptive options for which they are medically eligible so that they can identify the optimal method.

Unintended Pregnancy and Increased Health Risk

For women with conditions that might make pregnancy an unacceptable health risk, long-acting, highly effective contraceptive methods might be the best choice to avoid unintended pregnancy (Figure). Women with these conditions should be advised that sole use of barrier methods for contraception and behavior-based methods of contraception might not be the most appropriate choice because of their relatively higher typical-use rates of failure (Figure). Conditions included in the U.S. MEC that are associated with increased risk for adverse health events as a result of pregnancy are identified throughout the document (Box 2). Some of the medical conditions included in U.S. MEC recommendations are treated with teratogenic drugs. While the woman’s medical condition may not affect her eligibility to use certain contraceptive methods, women using teratogenic drugs are at increased risk for poor pregnancy outcomes; long-acting, highly effective contraceptive methods might be the best option to avoid unintended pregnancy or delay pregnancy until teratogenic drugs are no longer needed.

Keeping Guidance Up to Date

Updating the evidence-based recommendations as new scientific evidence becomes available is a challenge. CDC will continue to work with WHO to identify and assess new relevant evidence as it becomes available and to determine whether changes in the recommendations are warranted (7). In most cases, U.S. MEC follows the WHO guidance updates, which typically occur every 5 years (or sooner if warranted by new data). However, CDC will review all WHO updates for their application in the United States. CDC also will identify and assess any new literature for the recommendations and medical conditions that are not included in the WHO guidance. CDC will completely review U.S. MEC every 5 years as well. Updates to the guidance will appear on the CDC U.S. MEC website (https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/UnintendedPregnancy/USMEC.htm).

Acknowledgements

This report is based, in part, on the work of the Promoting Family Planning Team, Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, and its development of Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 5th edition.

References

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52.http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1506575 PubMed

- Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann 2008;39:18–38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x PubMed

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care: national and state estimates for 2010. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2015.

- World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009.

- CDC. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59(No. RR-4). PubMed

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-4).

- Mohllajee AP, Curtis KM, Flanagan RG, Rinehart W, Gaffield ML, Peterson HB. Keeping up with evidence a new system for WHO’s evidence-based family planning guidance. Am J Prev Med 2005;28:483–90.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.008 PubMed

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 PubMed

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 PubMed

- Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al; Methods Work Group, Third US Preventive Services Task Force. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(Suppl):21–35.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6 PubMed

- Horton L, Folger SG, Berry-Bibee E, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, Curtis KM. Research gaps from evidence-based contraception guidance: the U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016, and the U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. Contraception. In press 2016.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015;64(No. RR-3). PubMed

FIGURE. Effectiveness of family planning methods

Sources: Adapted from World Health Organization (WHO) Department of Reproductive Health and Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP). Knowledge for health project. Family planning: a global handbook for providers (2011 update). Baltimore, MD; Geneva, Switzerland: CCP and WHO; 2011; and Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404.

* The percentages indicate the number out of every 100 women who experienced an unintended pregnancy within the first year of typical use of each contraceptive method.

- Page last reviewed: February 1, 2017

- Page last updated: February 1, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir