A Career Lieutenant and a Career Fire Fighter Found Unresponsive at a Residential Structure Fire Connecticut

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2010-18 Date Released: June 1, 2011

Executive Summary

On July 24, 2010, a 40-year-old male career lieutenant (Victim #1) and a 49-year-old male career fire fighter (Victim #2) were found unresponsive at a residential structure fire. The victims and two additional crew members were tasked with conducting a primary search for civilians and fire extension on the 3rd floor of a multifamily residential structure. The fire had been extinguished on the 2nd floor upon their entry into the structure. While pulling walls and the ceiling on the 3rd floor, smoke and heat conditions changed rapidly. Victim #1 transmitted a Mayday (audibly under duress) that was not acknowledged or acted upon. Minutes later the incident commander ordered an evacuation of the 3rd floor. As a fire fighter exited the 3rd floor, Victim #1 was discovered unconscious and not breathing, sitting on the stairs to the 3rd floor. Approximately 7 minutes later, Victim #2 was discovered on the 3rd floor in thick, black smoke conditions. Both victims were removed by the rapid intervention team (RIT) and other fire fighters who assisted them. Both victims were pronounced dead at local hospitals.

|

Incident structure following extinguishment. |

Contributing Factors

- Failure to effectively monitor and respond to Mayday transmissions

- Less than effective Mayday procedures and training

- Inadequate air management

- Removal and/or dislodgement of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) facepiece

- Incident safety officer (ISO) and rapid intervention team (RIT) not readily available on scene

- Possible underlying medical condition(s) (coronary artery disease)

- Command, control, and accountability.

Key Recommendations

- Ensure that radio transmissions are effectively monitored and quickly acted upon, especially when a Mayday is called

- Ensure that Mayday training program(s) and department procedures adequately prepare fire fighters to call a Mayday

- Train fire fighters in air management techniques to ensure they receive the maximum benefit from their SCBA

- Ensure that fire fighters use their SCBA during all stages of a fire and are trained in SCBA emergency procedures

- Ensure that a separate incident safety officer (ISO), independent from the incident commander, is appointed at each structure fire with the initial dispatch

- Ensure that a rapid intervention team (RIT) is readily available and prepared to respond to fire fighter emergencies

- Consider adopting a comprehensive wellness and fitness program, provide annual medical evaluations consistent with NFPA standards, and perform annual physical performance (physical ability) evaluations for all fire fighters.

|

Incident scene. |

Introduction

On Saturday, July 24, 2010, a 40-year-old male career lieutenant (Victim #1) and a 49-year-old male career fire fighter (Victim #2) were found unresponsive at a residential structure fire. Both were transported to local hospitals where they were pronounced dead. On July 26, 2010, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On July 30, two safety and occupational health specialists from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program (FFFIPP) traveled to Connecticut to investigate this incident. The NIOSH investigators met with the deputy fire chief and representatives from the local fire fighters' union; the fire department's training division; the State of Connecticut Department of Public Safety, Division of State Police, Office of State Fire Marshal; health department; the local civil service director; private ambulance service; and the State of Connecticut's Department of Labor, Division of Occupational Safety and Health (CONN-OSHA). Interviews were conducted with the deputy fire chief, training division staff, the health department physician, a member of the fire fighter's union safety and productivity committee, the incident commander (IC), the general manager of the private ambulance service, fire fighters who were on scene, and the director of public safety communications. NIOSH investigators met with the state police to inspect and photograph the victims' structural fire fighting gear and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) involved in the incident, and to review witness statements, photographs, and other available information obtained during their investigation. The NIOSH investigators visited, documented, and photographed the fire scene and structure. The NIOSH investigators reviewed the victims' pre-employment medical evaluations, annual medical evaluations, annual respirator fit testing, and medical examiner reports. The NIOSH investigators also reviewed training records for the victims and the IC, dispatch radio transcripts, photos and videos taken by bystanders, department standard operating procedures (SOPs), and SCBA air quality testing results and maintenance records. On January 20, 2011, a NIOSH investigator and the NIOSH Fatality Investigations Team Chief returned to Connecticut to meet with the fire chief and with representatives with CONN-OSHA and the state police.

Fire Department

This career fire department has 8 stations with 292 uniformed members which serve a population of approximately 140,000 within an area of about 17 square miles. At the time of the incident the fire department had 9 engines, 4 aerial ladders, and a heavy rescue truck.

Fire Department Operations

Field personnel within the fire department are divided into four platoons to cover two shifts a day. Each platoon works three straight 10-hour day shifts, followed by three days off, then three straight 14-hour night shifts. This averages out to a 42-hour workweek. Fire fighters can work overtime, which allows them to work 24 or more hours in a row.

The fire department's training division works from 0900 to 1630, Monday through Friday. The training division is responsible for assigning a designated incident safety officer (ISO) to respond to incidents that require one (e.g., hazardous materials responses and confirmed working structure fires). Training staff within this division are assigned as the on-duty ISO during normal duty hours. After normal business hours and on weekends, an ISO is placed on an on-call status. The ISO is dispatched per dispatch protocols or upon request from the IC. The ISO will respond in a fire department vehicle from his/her home to the incident location with all required equipment to perform their duties.

The fire department has written operational procedure guidelines, standard operating procedures, and directives (OPG/SOP/D) that cover a wide range of administrative and operational topics.1 Those OPGs/SOPs/Ds specific to this incident include the following:

- Mayday Procedures (see summary of procedure in Appendix I)

- SCBA Operation and Maintenance Instructions

- Use of SCBA

- SCBA Emergency Escape

- Personal Alert Safety System (PASS) Devices

- Rapid Intervention Team (RIT)

- Emergency Evacuations

- Radio Operation Instructions

- Radio Usage Guidelines

- Radio Guidelines for Fire Ground Channels

- Initial Dispatch and Multiple Alarm Procedures

- Incident Command System

- Accountability System

- Engine and Truck Company Operations and Responsibilities

- Training Requirements

The fire department does not have a procedure or guideline for fire fighter rehab at emergency incidents.

A contracted private ambulance service provides emergency medical services (EMS) to the city and to the fire department. The fire department may first respond to medical emergencies dispatched within the city limits to assist the ambulance service. Emergencies requiring EMS are routed through the city's dispatch center and then transferred to the ambulance dispatch center, which then logs all information before dispatching the appropriate station for an ambulance to respond. No procedures or guidelines are established between the ambulance service and fire department stating that an ambulance will be automatically dispatched to standby at a fire-related incident to render medical care and rehab services to fire fighters or civilians on scene when needed.

9-1-1 Communications Center

In April 2010, the city’s fire and police 9-1-1 centers were consolidated into a new public safety communications department through a grant. Fire department lieutenants assigned to the original fire department 9-1-1 center did not transition into the new communications department, but were reassigned to the field. Civilian fire dispatchers from the fire department’s 9-1-1 center did transfer into the new communications center. Prior to the communications center’s opening, all fire dispatchers were trained on the new computer-aided dispatch and radio systems and had taken or were scheduled to take an advanced fire service dispatch class. Note: Dispatchers hired after 1990 were certified as telecommunicators through the State of Connecticut, Office of Statewide Emergency Telecommunications.

These civilian fire dispatchers had been trained on fire department policies and dispatch procedures by fire department personnel prior to transferring to the new communications center. Training included fire department procedures on handling a Mayday, and the fire department had also established a Mayday procedure test to check the viability of the Mayday SOP. According to the fire department's SOP, this test was conducted every first day shift (Monday morning) (see summary of procedures in Appendix I).

NIOSH investigators were able to meet with and interview the communications center director regarding the incident and history of the new communications center. However, NIOSH investigators did not have an opportunity to interview the actual dispatcher(s) who worked the 9-1-1 console or the supervisor(s) on duty the day of the incident. According to the communications center director, two fire dispatchers (1 originally from the fire department's 9-1-1 center) handled the fire incident. Together, they had 40 years of dispatching experience for fire and police. Two supervisors were also available in the communications center during the incident. According to training records received, the two dispatchers and two supervisors held a current State of Connecticut certification as a Public Safety Telecommunicator. The supervisors had also been certified as a Communications Center Supervisor by the Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials, or APCO.

Coincidentally, following the incident, the fire department worked with the new communications center on installing equipment that would boost radio signals in dead areas, based on problems in previous incidents. The fire department does not recall having any radio transmission problems during the incident.

State Regulations

The State of Connecticut operates an occupational safety and health program in accordance with Section 18(b) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. CONN-OSHA has adopted all federal OSHA standards that apply to public sector employers. CONN-OSHA enforces fire department compliance with the following regulations:

- Fire Brigades2 29 CFR 1910.156(b)(1), 1910.156(c), 1910.156(c)(2), 1910.156(d)(1), 1910.156(e)(1-5)

- Respiratory Protection3 29 CFR 1910.134(c), 1910.134(e), 1910.134(f)(2), 1910.134(g)(1), 1910.134(g)(3), and 1910.134 (h)Note: This list only contains enforceable regulations related to fire incidents.

Following their investigation, CONN-OSHA determined that the fire department had violated regulations set forth by the Connecticut's Occupational Safety and Health Act. As of January 24, 2011, these citations included:

- The employer did not furnish employment and a place of employment which were free from recognized hazards that were causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees in that the employer did not follow their existing Standard Operating Procedures regarding “Maydays”.

- The employer did not follow existing Standard Operating Procedures regarding “Maydays” on July 24, 2010.

- 1910.101 (a): The employer did not determine that compressed gas cylinders under his control were in safe condition to the extent that can be determined by visual inspection. Visual and other inspections were not performed as prescribed in the Hazardous Materials Regulation of the Department of Transportation (49 CFR parts 171-179 and 14 CFR part 103). Where those regulations are not applicable, visual and other inspections shall be conducted in accordance with Compressed Gas Association Pamphlets C-6-1968 and C-8-1962, which incorporated by reference.

- Hydrostatic testing was not performed on all SCBA air cylinders that were worn by fire fighters who perform interior structure firefighting.

- 1910.134(e)(1): Medical evaluations were not provided to employees to determine the employee’s ability to use a respirator, before the employee is fit tested or required to use the respirator in the work place.

- Employer did not ensure that medical evaluations were performed on employees who wear self containing breathing apparatus (SCBA).

- 1910.134(f)(2): The employer shall ensure that an employee using a tight-fitting facepiece respirator is fit tested at least annually.

- Annual fit testing was not performed on fire fighters who wore self contained breathing apparatus while performing interior structure firefighting.

- 1910.134(g)(4)(iii): The employer did not ensure that each employee engaged in interior structural firefighting operations used SCBAs.

- The employer did not ensure that all fire fighters wore self contained breathing apparatus while performing all aspects of interior structure firefighting on July 24, 2010.

Health, Wellness, and Fit-for-duty Program

In 1999, this fire department suffered a medical line-of-duty death that was investigated by NIOSH.4 NIOSH recommendations following that incident included the following:

- Conduct annual medical evaluations of all fire fighters to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves and others

- Reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity by phasing in a mandatory wellness/fitness program for fire fighters

- Perform an autopsy on all on-duty fire fighters whose death may be cardiovascular related.

In early 2000, the fire department applied for a health and wellness grant that enabled them to purchase physical fitness equipment for all stations and nutritional services for approximately 2 years. At the time of the incident, fire fighters were allowed to work out at their own discretion, but no requirements or programs were established for physical fitness.

The city requires all fire fighter candidates to pass a pre-employment medical evaluation, a physical agility test, and a respirator fit test. The pre-employment medical evaluations are performed by a physician contracted by the city. The evaluation consists of a medical history, a physical examination, blood tests (complete blood count, chemistries, and lipids), urinalysis, spirometry, a resting electrocardiogram (EKG), an exercise stress test, a chest x-ray, a vision test, a hearing test, and a drug screen. Both victims successfully passed their pre-employment medical physicals.

In 2006, the fire department began offering annual medical evaluations conducted by the city's health department. The components of this evaluation are the same as the pre-employment evaluations, minus the exercise stress test, blood test, and urine drug screen. In 2007, some screening tests were added. The additional mandatory tests included pulse oximetry, color vision screening, and scoliosis screening. The additional optional tests included prostate examination; fecal blood test for colon cancer; and blood tests for diabetes, anemia, and hypercholesterolemia. In 2008, a clinician change in the health department resulted in most fire fighters not receiving their annual medical evaluation for that year, but the medical evaluations were quickly reinstated in 2009. Both victims passed their 2009 medical evaluations. In June 2010, the health department clinician made a recommendation that the fire department's annual physical evaluation meet requirements set forth in National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1582 Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments.5

The city does not use the International Association of Fire Fighters/International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFF/IAFC) Fire Service Joint Labor Management Candidate Physical Ability Test (CPAT) Program, which was developed as a fair and valid evaluation tool to assist in the selection of fire fighters and to ensure that all fire fighter candidates possess the physical ability to complete critical tasks effectively and safely.6 Note: The fire department has been working with city officials to bring such a test to their department. Currently, the State of Connecticut, Commission on Fire Prevention and Control offers the CPAT to interested fire fighter candidates.

In 2002, Victim #2 passed the city delivered pre-employment physical agility and strength test protocol, which consisted of: (a) torso bend and arm lift, (b) ground ladder climb, (c) stair climb, (d) sit-ups, (e) hose hoist, (f) dummy carry, and (g) dry hose pull, but he was not tested on the ground ladder climb or hose hoist. Hired in 2007, Victim #2 was not required to retake the pre-employment physical agility and strength test that he took in 2002, which made those test result 5 years old at the time of his hiring. Victim #1 was hired in 1994, and no pre-employment physical agility test records were available for Victim #1. At the time of the incident, the fire department did not require fire recruits or members of their department to pass an annual physical agility test.

The fire department annually fit tested (in house) fire department members who were required to wear a respirator or SCBA pursuant to the requirements of OSHA regulation 29 CFR 1910.134.3 Note: NIOSH investigators did not confirm if all members of the fire department had received an annual fit test. Both victims successfully completed fit testing in January 2009; they had not received their 2010 fit test by the time of the incident.

Training and Experience

The fire department's training division oversees the department's recruit training program. The length of the training program has changed over the years and, at the time of the incident, was being conducted over a 14 week period. Victim #1 and Victim #2 completed their recruit training programs in 1994 and May 2008, respectively. The current recruit training program includes the following components:

- Orientation

- Fire Fighter I and II Certification (meets State of Connecticut Fire Academy certification requirements and NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications7)

- Medical Response Technician

- Hazardous Materials First Responder (Awareness and Operational levels)

- Incident Command System (ICS) 100, 200, and 700

- Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting Course

- Confined Space Rescue (Awareness level)

- 2Q (prepares potential fire apparatus operators; designed by the State of Connecticut, Department of Motor Vehicles)

- Physical Fitness Training (begins the 2nd week of recruit training; includes daily basic stretching exercises, walking and an untimed 3 mile run. No documentation is maintained on the progression of the recruit fire fighter’s physical fitness level.)

Victim #1 had been with this department for approximately 16 years. Victim #1 was hired in July 1994 as a fire fighter after serving 5 years with another career fire department. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant in February 2009. He held certifications in Fire Fighter I, Medical Response Technician, Hazardous Materials First Responder (Awareness and Operational levels), and Confined Space Awareness. He completed classes such as ICS 700, Fire Officer, Technical Rescue, and how to escape deadly situations inside burning buildings. He had also completed approximately 340 hours of documented yearly refresher training between 2004 and 2010; these hours included training on topics such as SCBA, safety, personal protective equipment (PPE), fire chemistry, and building construction.

Victim #2 had been with this department for approximately 2 years. Victim #2 was hired in December 2007 as a fire fighter with no prior firefighting experience. He held certifications in Fire Fighter I, Fire Fighter II, and Medical Response Technician. He completed classes such as ICS 100, 200, and 700a. He had also completed approximately 212 hours of documented yearly refresher training between 2009 and 2010; these hours included training on topics such as SCBA, safety, PPE, fire chemistry, and building construction.

The IC, at the time of the incident, had been with this department for approximately 33 years, holding the rank of a battalion chief for the past 5 years. Prior to becoming a battalion chief he held the rank of a captain (9 years), a lieutenant (6 years), pumper/engineer (2 months), and fire fighter (13 years). He held certifications in Fire Fighter I, Medical Response Technician, Hazardous Materials First Responder (Operational level), and Confined Space Awareness. He completed classes such as Engine and Aerial Company Operations, Marine Fire Fighting, RIT, and how to escape deadly situations inside burning buildings. He had also completed documented courses on ICS, strategies and tactics, and command officer training including ICS in 1994 (in house/National Fire Academy), ICS Training in 1997 (in house), Managing Company Tactical Operations Simulations in 2001 (state fire academy), Strategy and Tactics in 2004 (in house), IS-700 National Incident Management System in 2006 (Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)/Emergency Management Institute), Chief Officers Training in 2006 (third party), ICS 300 in 2007 (FEMA), and ICS 400 in 2008 (state fire academy). Note: Hours associated with these courses were not included in the IC's training record. Also, this may not constitute a complete list of training completed on ICS, strategies and tactics, and command officer training for the IC. The IC had also completed approximately 136 hours of documented yearly refresher training between 2004 and 2010; these hours included training on topics such as SCBA, safety, hazardous materials, fire chemistry, and building construction.

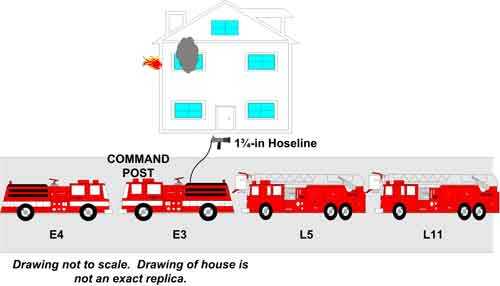

Equipment and Personnel

1st Alarm Assignment:

- Engine 3 (E3) with an engineer, two fire fighters, and a captain

- Ladder 5 (L5) with an operator, two fire fighters, and a lieutenant (initial IC)

- Engine 4 (E4) with an engineer, two fire fighters, and a lieutenant

- Rescue 5 (R5) with a driver, three fire fighters (FF1, FF2, FF3), and a captain

- Ladder 11 (L11) with an operator, two fire fighters (FF4 and Victim #2) and a lieutenant (Victim #1)

- Engine 1 (E1) with an engineer, two fire fighters, and a captain

- Engine 7 (E7) as the initial RIT with an engineer, two fire fighters, and a lieutenant

- Battalion 1 (B1) with an aide (BA)

Note: See Diagram 1 for incident scene.

Additional units requested by the IC and/or dispatched to the scene:

- Deputy Chief (DC)

- Incident Safety Officer (ISO)

- Engine 12 (E12) to take over as RIT, with an engineer, two fire fighters, and a lieutenant

- Ambulance 7116 (A7116) with basic life support

- Ambulance 7110 (A7110) with basic life support

- Ambulance 7126 (A7126) with advanced life support

Personal Protective Equipment

It was reported to NIOSH investigators that both victims entered the structure wearing a full array of personal protective equipment (PPE) and clothing, consisting of turnout gear (coat and pants), helmet, Nomex® hood, gloves, boots, and a SCBA with an integrated personal alert safety system (PASS) device. According to fire fighters interviewed by NIOSH investigators and state police witness statements, Victim #1 was found to be cyanotic with his facepiece suctioned to his face. The fire fighter who discovered Victim #1 did not recall hearing his PASS device alarming. Victim #2 was discovered with his facepiece properly connected to his regulator, but not positioned on his face. Victim #2's PASS device was alarming when he was discovered in the house. Both sets of turnout gear had their heat-resistant outer shells, moisture barriers, and insulating thermal linings present during the incident and documented during the investigation.

Both victims were equipped with handheld radios. The state police investigator reported to NIOSH investigators, during his inspection, that Victim #1's radio was still operable, including the emergency button; however, the radio believed to be Victim #2's was found to be inoperable, even after the batteries were replaced. Note: NIOSH investigators cannot confirm if Victim #2's handheld radio was operable during the incident, but the radio that was designated for his position on the apparatus was keyed several times on the main dispatch channel while Victim #2 was being removed from the house.

The victims' SCBAs were secured and retained by the state police investigators. NIOSH investigators were able to photograph and document both SCBAs. Both SCBA cylinders were 30-minute, 4500-psi units. The SCBAs did not appear to be degraded from fire or heat but did shown signs of wear and tear. The SCBAs were manufactured in 2008 and found to be certified under the 2007 editions of NFPA 1981 Standard on Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) for Emergency Services and NFPA 1982 Standard on Personal Alert Safety Systems.8,9 Victim #1's SCBA cylinder was manufactured in September 1998 and had a stamped hydrostatic test date on the cylinder of April 2003. Victim #2's SCBA cylinder was manufactured in January 2004 but did not visually appear to have a stamped hydrostatic test date on the cylinder. Therefore, due to applicable DOT standards, it appeared that both SCBA cylinders were due for repeat hydrostatic testing in 2008 and 2009 respectively (every 5 years). The victims' SCBAs were evaluated by the NIOSH National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) to determine conformity to the NIOSH-approved configuration (see Appendix II). Information contained in the PASS device data logger was also downloaded with assistance from the SCBA manufacturer (see Appendix II). The victims' structural fire fighting gear and PPE were also examined by NPPTL to determine conformity to NFPA voluntary consensus standards. Note: This evaluation report will be added to this report as Appendix III, when completed. NIOSH investigators do not believe that the PPE had any direct contribution to the two fire fighter deaths.

The fire department maintains their SCBA equipment and compressed breathing air refill system. The SCBA maintenance shop has manufacturer-certified technicians who work on the SCBAs. In May 2010, the fire department's stationary and mobile air refill system was evaluated by a third party and found to be in compliance with NFPA 1989 Standard on Breathing Air Quality for Emergency Services Respiratory Protection, 2008 edition,10 and Compressed Gas Association G-7.1-2004 Grade E standards and regulations.

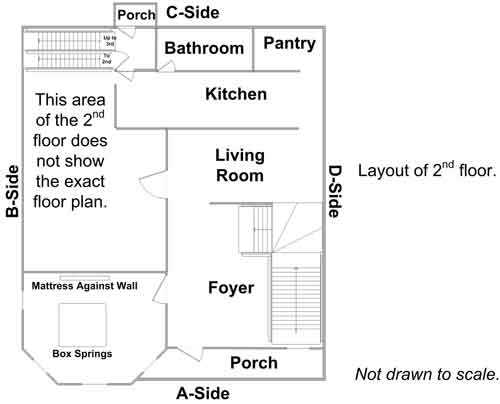

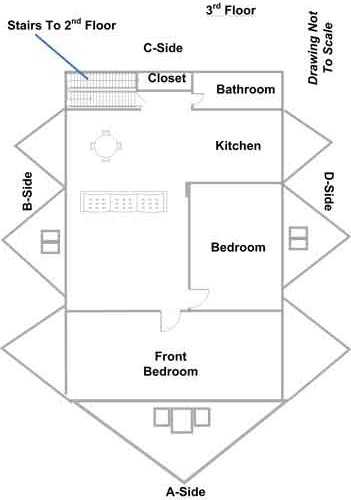

Structure

Built in the early 1900s, the two-and-half-story house (see Photo 1) was purchased approximately 4 years prior to the incident as a multifamily rental occupancy. One family lived in the 1st floor apartment (approx. 1,300 sq. ft.); a second family lived in the 2nd floor apartment (approx. 1,300 sq. ft.) (See Diagram 2), and the owner occupied the finished half-story or attic space (approx. 700 sq. ft.) (See Diagram 3). The house also contained an unfinished basement (approx. 1,300 sq. ft.). The common front entrance contained access to the 1st floor apartment and a private stairwell, located at the A/D corner of the house, which provided access to the 2nd floor apartment. The house also had a single rear-entry door that provided access to a stairwell that led up to the owner's apartment and had landings to access all the apartments from the rear. According to the owner of the house, smoke detectors were installed within the house about a year prior to the incident. These smoke detectors were installed in every bedroom, in each hallway, and in the stairwells. The house did not have an installed sprinkler system and had been inspected in accordance with Department of Housing and Urban Development Section 8a guidelines, according to the homeowner. The house was Type V wood frame construction, but, during the initial stages of the fire, was presumed by arriving fire fighters to be balloon-framed due to the era when it was constructed. State fire investigators were able to confirm Type V construction after closer inspection.

|

|

Photo 1. A-side of house during cleanup operations. |

The Office of the State Fire Marshal's building code compliance inspection showed that the house did not meet certain Connecticut Fire Safety Code requirements for this type of structure. NIOSH investigators do not believe that these non-compliance issues contributed to the deaths of the two fire fighters.

aFederal assistance provided by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. Under the program, the owner(s) of the property receive rent subsidies to assist qualified low-income tenants in paying their rent.

Weather Conditions

The weather on July 24, 2010, was abnormally warm for this area. Temperatures were in the 90s with a heat index above 100°F. Partly cloudy skies and approximate winds of 10 miles per hour from the southwest were observed. Research by the National Institute of Standards and Technology has shown wind speeds on the order of 10 to 20 mph (16 to 32 km/hr) are sufficient to create wind-driven fire conditions in a structure with an uncontrolled flow path.11 The weather caused heat exposure issues for fire fighters. The fire department does not have an emergency incident rehabilitation policy and several fire fighters received medical care on scene by EMS personnel, with some requiring transport to local hospitals for heat-related emergencies. Although water was provided to fire fighters during the incident, no rehab area was established.

Timeline

This timeline is provided to set out, to the extent possible, the sequence of events according to recorded and intelligible radio transmissions. Two channels were used during this incident: the main dispatch channel and channel 2 (fireground). Times are approximate and were obtained from review of the dispatch records, witness interviews, photographs of the scene, and other available information. Times have been rounded to the nearest minute. NIOSH investigators have attempted to include all intelligible radio transmissions, but some may be missing. This timeline is not intended, nor should it be used, as a formal record of events.

- 1544 Hours

E3 and L5 dispatched to a report of an elevator rescue. - 1546 Hours

While en route, E3 contacted the dispatcher on the main dispatch channel and advised them they needed to redirect all companies to a possible house fire. - 1547 Hours

L5 copied E3's transmission on the main dispatch channel and redirected to the possible house fire.

E3 advised the dispatcher, on the main dispatch channel, that they had a fire on the 2nd floor and that they did not have a hydrant. Note: It is unclear whether E3 established command, but L5 arrived just after E3 and established command. - 1548 Hours

E3, E4, E1, E7 as RIT, L11, L5, R5, and B1 were dispatched on the main dispatch channel to the house fire. - 1549 Hours

L5 arrived on scene and their officer stated over the main dispatch channel, "2½-story wood frame with heavy fire coming from the 2nd floor, Alpha/Bravo side, L5 is now command." - 1550 Hours

E7 en route. - 1551-1552 Hours

E4 arrived on scene and laid a supply line in from the hydrant.

Over the main dispatch channel, L5 officer (initial arriving IC) advised the dispatcher that the bulk of the fire was knocked down by E3 and the primary search was in progress.

Over the main dispatch channel, the dispatcher advised L11 and E7 which way they should approach the scene.

Over the main dispatch channel, L5 officer requested an ambulance for an injured fire fighter (ankle injury).

Over the main dispatch channel, B1 advised the dispatcher that he was on scene, and he confirmed the first report of heavy fire with the bulk of the fire knocked down. B1 then took command of the incident. - 1553 Hours

L11 arrived on scene.

E1 took an additional hydrant.

A7116 dispatched to the incident for an injured fire fighter. Note: Dispatch of A7116 was not part of the initial fire assignment. The 9-1-1 center contacted the EMS dispatch center via landline to request an ambulance for the injured fire fighter on scene after the request from the L5 officer. - 1554 Hours

Over the main dispatch channel, the BA advised the dispatcher that the command post would be in front of the fire building and tag collection would be at the command post. On channel 2, E4 officer asked E3 to charge the second hoseline. E7 (RIT) arrived on scene. - 1555 Hours

On channel 2, E4 officer asked E3 again to charge the second hoseline.

Over the main dispatch channel, the IC requested the dispatcher to have the safety officer respond to the incident.

IC checked on the status of the ambulance.

Fire dispatch advised the IC that the ambulance was en route. - 1556 Hours

E3 advised the IC (on the main dispatch channel) that he needed hooks on the 2nd floor in the room of origin; the IC acknowledged the request.

Over the main dispatch channel, IC advised all companies, “Channel 2 fireground, channel 2 fireground.” Note: Up to this point, companies on scene were operating on the main dispatch and channel 2. Fire dispatch assigned fireground operations to channel 2 for the incident. - 1557-1558 Hours

IC called L11 on channel 2.

IC (on the main dispatch channel) confirmed with the dispatcher who was RIT (which was E7) on scene and advised them that their equipment was available at the command post.

Victim#1 acknowledged the IC’s request for L11 on channel 2, but the IC did not respond.

E3 officer, who incorrectly identified himself as “E4,” called command on channel 2 and stated they had a slight extension into the A/B corner. Note: He was working overtime the day of the incident at the station that houses E3 and E4, which is also his normal duty station.

The IC copied the E3 officer’s transmission on channel 2 and asked him if he had enough hooks available; the E3 officer stated he did.

A7116 arrived on scene. - 1559 Hours

E3 officer on channel 2 advised the IC that they needed a hoseline to the 3rd floor because they could not reach it (fire extension) from the 2nd floor.

The IC acknowledged the E3 officer’s transmission on channel 2.

The IC, on channel 2, advised Victim #1 that E1 was bringing a hoseline to the 3rd floor.

Victim #1 acknowledged the IC’s transmission on channel 2 and advised, “A primary is in progress, which is negative; and, they are still checking for extension.”

The IC acknowledged Victim #1’s transmission. - 1600 Hours

Over the main dispatch channel, the ISO advised the dispatcher that he was responding (from home).

A7116 contacted EMS dispatch requesting a single ambulance to standby at the incident per the IC.

A7110 dispatched and en route to fire to standby.

On channel 2, the IC (at the command post) advised the E4 officer that he could see fire extending up the A/B corner. Note: NIOSH investigators were not sure if this transmission was meant for the E4 officer or the officer from E3 who identified himself as E4. At 1559 hours, the E3 officer advised the IC of the extension to the 3rd floor.

On channel 2, the E4 officer advised the IC that he was working on getting a line up to the 3rd floor. - 1601 Hours

Over the main dispatch channel, the dispatcher advised the IC that the ISO and DC were responding.

On channel 2, the L5 officer contacted “L5-Alpha” (believed to be L5’s aerial ladder) to assist in the bucket; L5-Alpha acknowledged the transmission. - 1602-1603 Hours

On channel 2, the IC contacted the L5 officer to verify whether he thought he could make the roof with L5.

On channel 2, the L5 officer stated that he was sending the driver down to talk to him.

R5 officer advised the IC on channel 2 that the primary was negative on the 2nd floor.

E4 attempted to contact L5 on channel 2, but was walked-on by R5-Alpha attempting to contact the R5 officer twice.

E3 officer advised L5 on channel 2 that they needed to overhaul the porch on the 2nd floor, but he did not think L5 could get to it.

L5 officer acknowledged E3 engineer’s transmission on channel 2. - 1604 Hours

DC en route to the incident.

Over channel 2, R5 called the IC three times (no response).

Over channel 2, the E4 officer called the E3 pump operator twice to shut the fog nozzle hoseline down; the E3 pump operator acknowledged.

Victim #1 called the IC twice on channel 2 (no response). - 1605 Hours

Over the main dispatch channel, the IC requested another RIT from the dispatcher.

On channel 2, R5-Alpha advised the R5 officer that the primary above the fire floor (2nd floor) was complete.

On channel 2, the R5 officer attempted to contact the IC (no response).

E4 officer advised the E3 pump operator to recharge the fog nozzle hoseline; the E3 pump operator acknowledged. - 1606-1607 Hours

A7110 arrived on scene.

E12 dispatched and responded as the RIT. Note: At 1604 hours, E12 was en route to the elevator rescue.

On channel 2, the IC advised Victim #1 that he was getting a second hoseline to the 3rd floor for him. The IC asked Victim #1, “What’s the situation up there?”

Victim #1 stated, “We got the line in place, it’s charged, we have extension into the attic space…”

The IC then asked for Victim #1 to verify “if” he already had a line in place, but there was no response.

A member of E4 advised the IC that they had, “…line in operation on the number three floor.”

A7116 en route to hospital with injured fire fighter. - 1608 Hours

R5 contacted the IC on channel 2 and advised him that they had one line in operation and he recommended that the roof be opened. Note: A Vibralert® could be heard alarming during his transmission.

IC advised R5 that they were preparing ground ladders to access the roof. - 1609 Hours

E12 (RIT) arrived on scene.

Over the main dispatch channel, IC advised E12 of where the command post and equipment were located.

Victim #1 called command on channel 2 (no response).

IC and E1 personnel had a conversation on channel 2 about supplying water to an additional unit on scene. Note: Victim #1 keyed his radio prior to and just after this conversation, but no transmissions occurred. - 1610-1612 Hours

L5 officer called R5 on the main dispatch channel (no response).

On the main dispatch channel, the BA advised L5 and all companies to switch to channel 2.

E3 personnel contacted the IC on channel 2 and advised him that they might be able to open it (the roof) from the 2nd floor if they had hooks.

The IC called Victim #1 on channel 2 and was acknowledged, but no further transmissions occurred.

E4 (officer) called the nozzle man down to the 3rd floor. Note: At this point, the nozzle man may be the driver of R5.

L5 officer contacted R5 on channel 2.

R5 officer advised the L5 officer that they were operating on the 3rd floor and could not open the roof from there.

The IC attempted to contact Victim #1 on channel 2 (no response).

DC arrived on scene.

ISO arrived on scene. - 1613 Hours (1st Mayday Call)

On channel 2, FF2 called R5 (no response). He then called L11 (no response).

L5 officer advised L5-Alpha/Bravo to “come on down.” Note: L5-Alpha/Bravo is believed to be on the roof.

On channel 2, Victim #1 stated, “Mayday-Mayday-Mayday, we’re trapped on the rear stairs.” Note: This transmission was very quick lasting only 3 seconds. A Vibralert, presumed to be Victim’s #1, can be heard alarming during his transmission. Victim #1’s Mayday call was not acknowledged over the radio.

FF2 advised L11 on channel 2, “…fire below you, B-side.”

E1 personnel had a brief conversation on channel 2 regarding water supply.

The IC called L11 on channel 2 (no response).

An unknown fire fighter’s transmission is heard stating, “Negative on that opening, negative on that roof opening.”

The IC called L11 on channel 2 again (no response). - 1614 Hours

The IC called E1 on channel 2 (no response).

The IC called the L11 officer (Victim #1) on channel 2 (no response). - 1615 Hours

On channel 2, the IC stated, "Command to all companies on the 3rd floor, vacate the 3rd floor; I repeat, command to L11 and E1, vacate the 3rd floor." - 1616-1619 Hours 2nd Mayday Call)

The IC attempted to contact L11 again on channel 2 (no response).

The IC, on channel 2, then stated, “Command to E1.”

(1616.50 hours) On channel 2, FF2 stated, “Mayday, Mayday…Rescue 5 Bravo command we have a downed fire fighter rear steps. Mayday-Mayday-Mayday fire fighter down rear steps, 2nd floor.”

IC called L11 again on channel 2 (no response).

FF4 on channel 2 stated, “Ladder 11 irons to Ladder 11” (no response). Note: An apparatus air horn is heard sounding in the background of this transmission.

FF2 on channel 2 stated, “Rescue 5 Bravo command, Rescue 5 Bravo command we need help 2nd floor, send the RIT, we need fresh bodies.” Note: No audio transmissions or emergency tones are heard on channel 2 or the main dispatch channel advising that the Mayday call had been acknowledged.

DC contacted the IC on channel 2 to have him send the RIT to the rear stairs; the IC acknowledged. Note: The RIT may have already been advancing up the rear stairs, but they ran into difficulty accessing the 2nd floor landing off the rear stairs because a charged hoseline was against the closed door.

Dispatch attempted to contact command on channel 2 (no response).

The IC called L11 again on channel 2 (no response).

The DC contacted the IC requesting the ambulance on scene to come to the rear of the house.

Victim #1 was extricated out the rear of the house. - 1620 Hours

A7110 began medical care for the downed fire fighter (Victim #1).

Over the main dispatch channel, the BA requested an advanced life support ambulance to the fire scene.

A7126 was dispatched to intercept A7110 at the fire scene to provide advanced life support.

(~1620.35 Hours) The following transmission is heard on channel 2, “…Ladder 11 ‘mayday’ (very quick transmission)…Ladder 11 (unintelligible word(s)).” Note: The dispatch caller ID for this radio is designated as “L-11 FF3,” which was assigned to the fire fighter (designated as FF4 for this report) who later finds Victim #2 (see below 1624 hours). FF4 had not found Victim #2 at the time of this transmission.

On channel 2, FF4 stated, “Ladder 11 irons to Ladder 11 can” (no response). Note: “Ladder 11 can” was Victim #2’s designation that shift. - 1621 Hours

A7126 en route to fire scene. - 1622 Hours

On channel 2, the ISO advised the IC that the fire fighter (Victim #1) was removed and they needed to do a roll call for everyone on scene.

On channel 2, the IC advised all company officers that the “incident is taking a PAR” (personnel accountability report).

Officers began calling in their respective PARs - 1624 Hours (3rd and 4th mayday Calls)

FF4 on channel 2 stated, "Mayday-Mayday, I have a fire fighter trapped on the 3rd floor, Mayday-Mayday-Mayday 3rd floor." Note: This Mayday is for Victim #2. A PASS device is heard alarming during FF4's transmission.

On channel 2, the IC stated, “This is command to all companies, vacate the building, I report, command to all companies, vacate the building.”

FF4 on channel 2 stated again, “Mayday-Mayday-Mayday, I’ve got another fire fighter down, another one, 3rd floor, hurry!” - 1625 Hours

Over channel 2, the dispatcher stated, "For a Mayday," and activated the emergency evacuation tones. Note: It is unknown why the evacuation tones were sounded instead of the Mayday tones. Their evacuation tone is an alternating, high-low sound, similar to a European siren. Their Mayday tone is a rapid, high to low pitch, chirping sound. This was dispatch's first acknowledgement of a Mayday over the radio. No further radio traffic regarding the Mayday was provided by the dispatcher following the tone activation on channel 2.

Over the main dispatch channel, the dispatcher stated, “For a Mayday,” and activated the emergency evacuation tones as well. No further radio traffic regarding the Mayday was provided by the dispatcher following the tone activation on the main dispatch channel. - 1626 Hours

The IC contacted the DC on channel 2. DC acknowledged with no further traffic from the IC.

The IC on channel 2 again advised all companies to vacate the building.

The dispatcher then activated the emergency tones on channel 2 and the main dispatch channel, and stated, “All companies per command vacate the building, all companies vacate the building.” - 1627 Hours

The ISO contacted the IC on channel 2 and stated, "We need to make contact with that Mayday, we need more information, we have not heard from them since the initial call."

On channel 2, the IC stated, “Command to company declaring a Mayday; I repeat, command to the company declaring a Mayday sound off, sound off.”

A fire fighter from the RIT advised the IC on channel 2 that they were moving the fire fighter off the 3rd floor.

On channel 2, the dispatcher advised the IC that the Mayday call was for the 3rd floor.

A7126 arrived at the fire scene. - 1628 Hours

RIT advised the IC that they have the fire fighter (Victim #2) on the 3rd floor and will be bringing him down the rear stairs from the 3rd floor. - 1630 Hours

A7110 en route to the hospital with Victim #1 without assistance from A7126. - 1632 Hours

ISO asked for a progress report from the RIT on the Mayday.

RIT replied, “Coming down…3rd floor.”

ISO asked RIT to repeat their traffic.

A radio was keyed, but there was no transmission. - 1634 Hours

RIT personnel advised the IC that they had the fire fighter (Victim #2) down to the 2nd floor landing. - 1640 Hours

A7110 arrived at local hospital with Victim #1. - 1643 Hours

A7126 began medical care on second downed fire fighter (Victim #2). Note: This time was taken from Victim #2's patient care report and may not be accurate. - 1703 Hours

A7126 arrived at local hospital with Victim #2.

Investigation

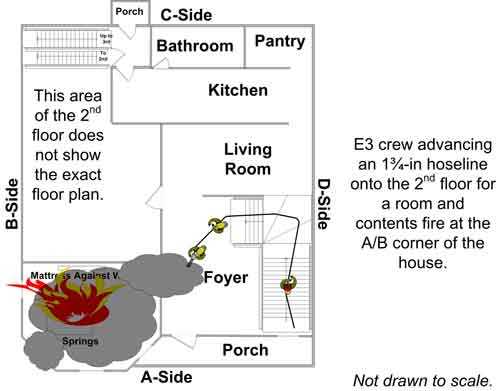

On Saturday, July 24, 2010, at 1544 hours, E3 and L5 were dispatched for a reported elevator rescue. While en route to this incident, personnel on E3 noticed smoke coming from a residential side street and immediately notified dispatch. E3 and L5 diverted to the residential side street. E3 arrived on scene first to find fire showing from the 2nd floor B-side window and smoke showing from the 2nd floor A-side windows (both windows located at the A/B corner). E3 was not able to lay a line into the scene because when they turned onto the residential side street they were unsure of which house was actually on fire. E3 pulled just past the house to allow room for L5 (see Diagram 1). The E3 officer exited E3 and quickly performed a size-up of the fire. The E3 officer felt that the fire could be quickly contained with the 500 gallons of water carried on E3 and the additional personnel arriving on L5. The E3 hydrant man and nozzle man exited the engine and pulled a dry 250-ft, 1¾-inch pre-connected attack line to the 2nd floor landing (see Diagram 4). The E3 officer assisted them in flaking the hose out before joining them on the 2nd floor landing. While this was taking place, L5 arrived on scene, gave a size-up over the radio, and established command for the incident. The E3 nozzle man opened the bail and had no pressure. The E3 officer exited the house and removed kinks in the hoseline with assistance from L5 personnel. The E3 officer returned to the house and noticed that his nozzle man was coming down the 2nd floor stairs in pain. The E3 officer stayed with his hydrant man (who was now on the nozzle) and quickly extinguished the room and contents fire on the 2nd floor. The L5 officer called for an ambulance and took care of the injured fire fighter who apparently had sustained an ankle injury while advancing the charged hoseline toward the fire room.

While E3 operated in the fire room, E4 arrived on scene and laid a 5-inch supply line into E3. R5, L11, L1, E7 (RIT), and BC had arrived or were also arriving on scene. Two L5 fire fighters followed shortly by two R5 fire fighters (driver and FF1) and R5's officer entered the house following E3's hoseline to the 2nd floor, and the L5 operator raised the ladder to the A/B corner of the house. The two L5 fire fighters performed a primary search of the 2nd floor and opened windows as they progressed to the rear stairwell. This stairwell provided them access to the 3rd floor so that they could continue their primary search and check for extension above the fire room. The two L5 fire fighters were met with light smoke conditions and hot temperatures when they reached the 3rd floor (prior to any windows being opened). These two L5 fire fighters recalled radio transmissions from the L5 officer regarding the fire being knocked down and the BC arriving on scene and taking command. As they were walking to pull the baseboards below the windows in the front room (the front room was at the A/B corner, directly above the fire room), personnel from R5 (FF2/FF3) and L11 (Victims #1 and #2 and FF4) entered the 3rd floor, and they assisted L5 with opening windows on the B- and D-sides of the 3rd floor. Note: Victim #1 received face-to-face orders from the IC to check on extension and ventilation on the 3rd floor. L11 personnel walked through the 1st floor apartment to the rear stairwell, not on air, and then walked up to the 3rd floor where they had to go on air. Victim #2 assisted with pulling the baseboards in the front room while FF2 and FF3 used a thermal imaging camera to check for hot spots and extension. Note: FF3 remembered speaking with Victim #1 in the kitchen area on the 3rd floor regarding the hot spots viewed on the thermal imaging camera and recalled hearing Victim #1 relaying the information to command. Opening the windows on the 3rd floor allowed cross ventilation, which quickly increased visibility on the 3rd floor, but the room was still extremely hot.

The E4 nozzle man and officer pulled the second hoseline from E3 to back-up E3 personnel working on the fire floor. This second hoseline was a 200-ft, 1¾-inch pre-connect with a fog nozzle. The R5 officer, who was paired up with FF1, left the driver of R5 to pull ceilings in the fire room. The R5 officer and FF1 went up to the 3rd floor to check on conditions. The R5 officer recalled bumping into Victims #1 and #2 and FF4 in the front room of the 3rd floor. FF1 then had to exit the 3rd floor because his Vibralert was alarming. Note: At this time, smoke conditions varied and personnel operating on the 3rd floor may not have been on air. The R5 officer and Victim #1 had a conversation about the thermal imaging camera (TIC) showing how hot the walls were and how they needed a hoseline. The R5 officer and Victim #1 advised all personnel on the 3rd floor not to open the walls or ceiling until they had a charged hoseline in place. Victim #1 had previously requested a hoseline. Note: At this point, E7/E1 may have been tasked by the IC with preparing an additional hoseline for the interior, thus removing E7 from the role of RIT. The IC then notified dispatch that he needed an additional engine company for RIT.

Once the E4 crew made it up to the 2nd floor it was determined that the hoseline was no longer needed in the fire room and the hoseline was redirected to the 3rd floor. This second hoseline only made it to the base of the stairwell that led to the 3rd floor. The E4 officer called for a "spare flake" and the E4 hydrant man and driver retrieved a 100-ft section of hose. This section of hose contained a smooth bore nozzle and a gated wye valve. When they returned with the extra section, the E4 officer ordered the E3 pump operator to shut down his hoseline. The E4 officer then left his crew at the base of the stairs to check conditions on the 3rd floor. The E4 nozzle man, hydrant man, and driver disconnected the fog nozzle from the second hoseline and connected the extra section with the smooth bore nozzle. The E4 officer recalled moderate smoke conditions, which were banked down to about chin level on the 3rd floor. He recalled moving furniture that was located above the fire room with personnel from R5 (FF2 and FF3). Note: The E4 officer does not recall the whereabouts of Victims #1 and #2. The two L5 fire fighters, who were operating on the 3rd floor, were ordered down (by the L5 officer) to begin roof ventilation operations. Note: The IC had observed smoke conditions on the B-side suggesting the roof needed to be vented. The E4 officer returned to the 2nd floor to assist the nozzle man and hydrant man in flaking and removing kinks from the hoseline before it was advanced to the 3rd floor. While they advanced the dry hoseline up to the 3rd floor, they were passed by R5 personnel (FF2 and FF3 and shortly after, possibly by the R5 officer), who were all exiting to get new air bottles. Note: While FF2 and FF3 were walking through the 2nd floor to leave, the officer of E3 asked them to assist with checking extension in the fire room. Both were out of air, but many fire fighters interviewed by NIOSH investigators stated that conditions on the 2nd floor did not require them to be on air. The E4 crew advanced the hoseline approximately 5-7 feet into the 3rd floor with assistance from FF4 and the E1 officer, and then the E4 officer called for the hoseline to be charged. The E4 officer recalled thick, black smoke banked down to just above floor level and the sound of fire around him (no visible fire) just prior to personnel opening the ceiling and walls. Personnel from R5 (driver) and possibly L11 continued opening the ceilings, dropping sheet rock around the hose crew. Note: The E4 hydrant man recalled fire fighters coming up the stairs as they were operating their hoseline. NIOSH investigators believe this may have been the R5 officer (returning with a fresh air bottle) and possibly personnel from E1 and/or E7.

The E4 nozzle man did not recall seeing any fire, but a lot of heat was released when the ceiling was opened. Thick black smoke was also released and pushed down to floor level. E4 continued to flow water on the 3rd floor when their nozzle man's Vibralert began to alarm. He handed the nozzle over to the R5 driver and followed the hoseline out. The E4 officer and hydrant man remained on the hoseline. The R5 officer remembered that when he returned to the 3rd floor, the hoseline stretched by E4 could not reach the A-side of the house, black smoke had completely obscured visibility, and the heat on the 3rd floor had intensified. The R5 officer recalled speaking to someone about getting more lines into the 3rd floor. Note: The R5 officer does not recall seeing Victims #1 or #2 on the 3rd floor at that time, and FF4 may have been in the process of exiting the 3rd floor to change his air bottle. Shortly following this, the Vibralert for both the E4 officer and hydrant man started alarming. The E4 officer spoke to two unknown fire fighters and advised them to take the hoseline and back up the fire fighter on the nozzle (driver of R5). The E4 officer and hydrant man exited the house to retrieve fresh air bottles. At some point, the R5 driver left the nozzle on the 3rd floor because his Vibralert was also alarming. He stated that he told 1 or 2 fire fighters that he was leaving the 3rd floor. Note: NIOSH investigators cannot confirm who he spoke to. The R5 officer exited the 3rd floor and saw a dry hoseline being flaked out on the 2nd floor, with assistance from FF1. Note: E7/E1 personnel were working on getting this hoseline into operation. The R5 officer exited the house and went to the command post to talk with the IC about how bad conditions were. It is unclear if the R5 officer walked to the A-side of the 3rd floor in the area of the front room prior to leaving the 3rd floor. NIOSH investigators cannot account for the exact location of Victims #1 or #2 on the 3rd floor. An E1 fire fighter stated that he operated a hoseline on the 3rd floor by himself (possibly after the R5 driver left) and heard a loud noise, immediately closed the nozzle, and yelled out to see if someone was there. He then left the 3rd floor.

NIOSH investigators believe that Victim #1 and Victim #2 were alone on the 3rd floor when Victim #1 transmitted, "Mayday-Mayday-Mayday, we're trapped on the rear stairs." His Mayday, lasting only 3 seconds, was never acknowledged over the radio by the 911 dispatcher(s), the IC, or other personnel on scene. While this was occurring, the dry, second hoseline was placed over the 3rd floor stairwell wall by an E1 fire fighter. FF2, still with FF3 in the fire room, radioed Victim #1 (directly following Victim #1's Mayday transmission) to let him know that the fire was below him, B-side, but he got no response, so he decided to walk back through the house to the rear stairwell. FF3 exited the house to retrieve a new air bottle. The IC was also attempting to call personnel who were last known to be on the 3rd floor, with no response, which ultimately led to the IC ordering an evacuation. The E12 officer (who took over RIT), the on-call DC, and the ISO who all had just arrived on scene moments before Victim #1's Mayday all stated they heard what they thought was a faint or muffled Mayday over the radio. The DC walked from his vehicle over to the command post and spoke to the IC and BA regarding the possible Mayday call; they were both unaware of the transmission. The E12 officer also approached the command post and spoke to the IC and DC regarding the Mayday. The IC was unaware of the Mayday transmission and the DC said he wasn't sure if he heard one. There was no acknowledgement for a Mayday over the radio from the 911 dispatcher(s). Note: There was no attempt to verify whether a Mayday was transmitted over the radio. The DC and E12 personnel (RIT) then proceeded to walk down the B-side of the house.

While this was occurring, FF1, who was still on the 2nd floor landing, followed the charged hoseline from E4 to the 3rd floor. He stopped short of the 3rd floor door because he saw the figure of a fire fighter coming toward him in a crouched position. This fire fighter, later identified as Victim #1, leapt from the 3rd floor onto the stairs going down to the 2nd floor, landing on a knee wall separating the ascending and descending sides of the stairwell. FF1 immediately grabbed Victim #1 by his SCBA harness and assisted him over the wall onto the descending stairs. FF1 reported that Victim #1 landed on his feet, facing the sub landing. Victim #1 then turned around and sat down on the stairs, facing the door leading out to the 2nd floor. FF1 looked at him for a few seconds and noticed that his facepiece was still on and no alarms were alarming. FF1 did not feel anything was out of the ordinary so he continued to the 3rd floor. FF1 continued to follow the charged hoseline to the 3rd floor, wondering why the roof had not yet been opened. Note: Once L5 personnel ascended the roof via a 28-ft ladder positioned on the B-side of the house, they were unable to operate the saw due to heavy smoke conditions emitting from the roof and eaves. FF1 stated that the smoke was extremely black and thick. He told NIOSH investigators that he came upon a fire fighter on the hoseline. FF1 did not have a conversation with this fire fighter; he thought maybe he was on the nozzle or backing the nozzle man up because he heard water spraying toward the A-side (water was being sprayed from the 2nd floor). Note: NIOSH investigators believe the fire fighter that FF1 came upon was Victim #2. NIOSH investigators cannot place any other fire fighters on the 3rd floor at this time. FF1 does not recall how this fire fighter was positioned. FF1 then heard the IC call over the radio for the building to be evacuated. FF1 immediately turned around and followed the hoseline out.

While descending the stairs, FF1 came upon Victim #1 still sitting in the same position he had left him, with his facepiece on and no alarms sounding. FF1 nudged Victim #1 and told him they had to evacuate the house. Victim #1 then slumped over. FF1 quickly grabbed him and began pulling him down the stairs to the 2nd floor. Personnel from E7 and E1, who were working on the 2nd floor just off the stairs, quickly assisted FF1. FF2 got to the rear of the 2nd floor and saw that Victim #1 was unconscious and being brought down the stairs by FF1 and personnel from E7 and E1. FF2 immediately called the Mayday for Victim #1. Note: Approximately, 3 minutes and 30 seconds passed from the time Victim #1 called his Mayday until FF2 called the Mayday for Victim #1. The RIT (E12) was heading into the backyard when they heard this Mayday transmitted. The DC, who also heard FF2's Mayday call, later alerted the IC to send the RIT to the backyard, but they were already heading up the rear stairs. The IC stated to NIOSH investigators that he did hear this Mayday transmission and he proceeded to the backyard. Dispatch did not acknowledge this Mayday call over the radio, nor were they advised of a Mayday occurring at the incident. The IC was still attempting to contact L11 (Victim #1) after FF2 transmitted the Mayday. FF4 returned to the 2nd floor via the A-side stairwell to see Victim #1 being cared for. FF4, realizing Victim #2 was not with Victim #1, attempted to contact Victim #2 with no response. The RIT immediately assisted with getting Victim #1 down the stairs to receive medical care. Note: The IC arrived at the backyard when Victim #1 was being carried from the house, so he ran back to the front of the house and alerted EMS personnel on scene. Once Victim #1 was outside the house, CPR was immediately initiated and an automated external defibrillator was attached. Only basic life support measures were initiated by EMS personnel on scene due to their level of training. FF4 exited out the rear stairwell and began looking for Victim #2 asking several fire fighters if they had seen Victim #2, but no one was sure where he was. It is believed at this point that FF4 made the decision to re-enter the house and search for Victim #2. The ISO advised the IC that they needed a PAR and the IC advised personnel over the radio. At this time, the ISO was requesting a PAR and the IC was notifying personnel that they needed to evacuate the house.

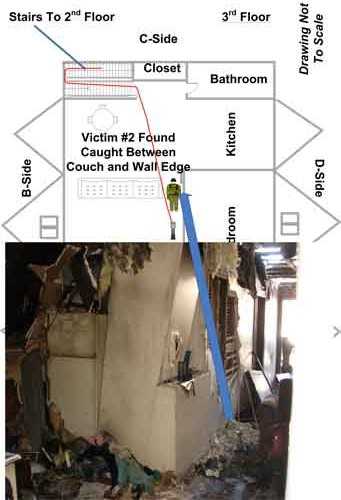

FF4 entered the rear stairwell and went to the 3rd floor (it is unclear if any personnel followed him into the house). He followed a hoseline into the 3rd floor and found Victim #2 apparently lodged between a wall and a piece of furniture (see Diagram 5). Victim #2's PASS device and indicator lights were alarming; he did not have his facepiece on. FF4 stated that he called a Mayday for Victim #2 and then heard evacuation tones over the radio and then air horns from an apparatus. He transmitted a second Mayday because the first one was not acknowledged by dispatch or the IC. Dispatch acknowledged the second Mayday for Victim #2 and set off the evacuation tones (not the Mayday tones), but no further radio traffic from dispatch or the IC confirmed the specifics of the Mayday. The ISO radioed the IC and advised him that they needed additional information on the Mayday that was just called. The RIT and other fire fighters located in the backyard were working on getting to Victim #2 and getting him off the 3rd floor and down the stairs. Many fire fighters at this point had gone through one or even two bottles and were exhausted. The RIT provided the IC with updates on their progress. The RIT recalled Victim #2 being caught between a sofa and a wall on his back with his arms out from his body when they found him (see Diagram 5). Victim #2 may have also been entangled in a hoseline. The RIT removed Victim #2 from the house, CPR was initiated and an automated external defibrillator was attached. Both victims were taken to local hospitals where they were pronounced dead.

NIOSH investigators can only speculate on what occurred on the 3rd floor that led Victim #1 to transmit a Mayday. FF1 stated to NIOSH investigators that he never heard the Mayday transmitted by Victim #1 and believed there were no causes for alarm when he saw Victim #1 exit the 3rd floor. FF1 does not recall hearing Victim #1's PASS device when he exited the 3rd floor or after he slumped over on the stairs. The victims' air packs were designed to go into pre-alarm within 20 seconds (can shake to reset) and then full alarm at 30 seconds (reset button must be used). Victim #1's facepiece was suctioned to his face when he was found. The question still remains why Victim #1 never removed his regulator or facepiece when he sat down on the stairs. It is unknown why Victim #2's facepiece was not positioned on his face. Both SCBA cylinders were empty upon inspection by state police investigators.

Fire Behavior

The room and contents fire was determined to have originated in a bedroom on the 2nd floor, A/B corner; it was quickly knocked down by E3 (see Photo 2). It is believed that the fire got into the eves when it was lapping out the A/B corner windows, and then spread within the large void spaces in the ceiling and walls of the 3rd floor. The fire was situated toward the A/B corner of the 3rd floor, but the open void areas allowed smoke to accumulate within the ceilings and walls before they were opened.

|

|

Photo 2. Remnants of a mattress and box springs within the room of origin on the 2nd floor. |

Operating on the 3rd floor at varying times were members from L5, R5, L11, E4, and E7. Initially, light-to-moderate smoke conditions were observed on the 3rd floor, depending on how close fire fighters were to the A-side of the 3rd floor. Fire fighters recalled the 3rd floor being very hot. TICs used by different individuals on the 3rd floor showed the room to be hot on the A-side and ceiling. Windows on the A-, B-, and D-sides were opened, allowing most of the smoke to self ventilate. Light smoke remained within the 3rd floor, with good visibility. Extension was checked around A- and B-side baseboards. Some fire fighters recall Victim #1 telling them the fire was in the ceiling and possibly the walls, and to not open those areas until a hoseline was in place. Even after providing horizontal ventilation on the 3rd floor, smoke conditions worsened, banking down to fire fighters' chin levels and becoming denser. While waiting for the hoseline, L5 members were reassigned by the IC to ventilate the roof to provide additional relief to the 3rd floor. The IC reported to NIOSH investigators that he ordered the roof vented because he saw smoke pushing out the B-side windows. Personnel from E4 advanced the charged hoseline to the 3rd floor, allowing the ceilings and walls to be opened. A mixture of thick, brown/black smoke quickly filled the room, reducing visibility. Photos 3-10 show conditions at the scene leading up to the first Mayday and then during the second Mayday.

|

Photo 3. Initial conditions observed when the BC arrived on scene at approximately 1551 hours. Note: Fire was under control on the 2nd floor and fire fighters were checking for extension. White-to-gray smoke can be seen flowing in the direction of right to left from the gables. The A-side window on the 3rd floor had been opened for ventilation (unsure at what stage of the fire or by whom). |

|

Photo 4. Conditions observed at 1608 hours by an off-duty fire fighter. Note: Smoke had changed to gray and brown in color and was emitting from the eaves and A- and D-side windows which were manually opened by personnel working on the 3rd floor. A hoseline was being stretched to the 3rd floor. |

|

Photo 5.Conditions at approximately 1609 hours. Note: L5 personnel were preparing to ascend the ladder placed on the B-side of the house. The IC (white helmet) is observing the scene. Smoke seen coming from the 3rd floor B-side double window and pushing from the eaves. At this time, ceiling and walls were likely being opened on the 3rd floor, and water would have been available. |

|

Photo 6. Conditions at approximately 1611 hours. Note: L5 personnel were ascending the roof from the ground ladder on the B-side. Smoke color was still gray to brown in color and was becoming denser. Personnel were still working on the 3rd floor. Wind direction was right to left. |

|

Photo 7. Conditions at approximately 1613 hours. Note: L5 personnel were on the peak of the roof and having difficulty starting the roof saw. Smoke was denser than before and pushing from the roof and eaves. The fire fighters were unable to vent the roof. NIOSH investigators believe that Victim #1 transmitted his Mayday about this time. |

|

Photo 8. Conditions at approximately 1616 hours. Note: View from the A/D corner, scene conditions very close to when FF2 discovered FF1 pulling Victim #1 off the 3rd floor stairs. White and gray smoke can be seen flowing from the A-side window and eaves while brown smoke flowed from the D-side window. |

|

Photo 9. Mayday for Victim #1, called by FF2. Note: RIT personnel from E12 are seen heading to the rear of the house. L5 personnel were descending the roof via the B-side ground ladder. Fire is seen burning along the roof line above the A/B corner. Gray, dense smoke was flowing from the 3rd floor B-side double window and A-side window. |

|

Photo 10. Fire vented through the roof. Note: NIOSH investigators believe this photo shows conditions very close to the time that the Mayday was called for Victim #2 by FF4. Wind was pushing the smoke plume from right to left. |

Contributing Factors

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatalities:

- Failure to effectively monitor and respond to Mayday transmissions

- Less than effective Mayday procedures and training

- Inadequate air management

- Removal and/or dislodgement of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) facepiece

- Incident safety officer (ISO) and rapid intervention team (RIT) not readily available on scene

- Possible underlying medical condition(s) (coronary artery disease)

- Command, control, and accountability.

Cause of Death and Injuries

Autopsies were conducted by the state medical examiner on both victims. Significant findings for Victim #1 included a focally severe occlusive coronary atherosclerosis (≥ 95% blockage) of his right coronary artery, 4 centimeters distal from its origin, and a carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) level of 4%, suggesting only minimal carbon monoxide exposure. His cause of death was listed as "asphyxia associated with smoke inhalation and exposure to fire." Significant autopsy findings for Victim #2 include patchy severe atherosclerosis, producing approximately 80% occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery and up to 60% occlusion of the mid-portion of the right coronary artery, and a COHb level of 44% (a level consistent with fatal carbon monoxide poisoning). His cause of death was listed as "smoke inhalation with other significant condition(s) of coronary atherosclerosis."

In addition to the deaths of the two fire fighters, the fire fighter from E3 suffered a broken ankle while advancing the hoseline, and numerous fire fighters suffered heat-related illnesses with 5 or 6 requiring transport to local hospitals.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: Fire departments and dispatch centers should ensure that radio transmissions are effectively monitored and quickly acted upon, especially when a Mayday is called.

Discussion: Fireground communications can become very hectic and confusing when a fire fighter is in distress, becomes lost, or is trapped. Fire departments and dispatch centers need to be able to effectively monitor radio transmissions (e.g., Maydays) while on the fireground and within a dispatch center. A Mayday procedure can outline the fireground response plan and duties of fire fighters, officers, the dispatch center, and the IC. This will help reduce any confusion during the Mayday.

The term "Mayday" is the international distress signal. Fire fighters must act promptly when they become lost, disoriented, injured, low on air, or trapped.12-17 They should announce "Mayday-Mayday-Mayday" over the radio and manually activate their PASS device. A transmission of the Mayday situation should be followed by the last known location of the fire fighter, and if able, the individual's identifier, such as "E3 pump." A crew member who suspects a fire fighter(s) is in trouble or missing should quickly try to communicate with the fire fighter(s) via radio and, if unsuccessful, initiate a Mayday providing relevant information.

An emergency radio transmission reporting a "Mayday" is the highest priority transmission that may occur at any incident and should receive precedence from dispatch, the IC, and other units operating at the incident. When this emergency traffic is initiated, all other radio traffic should stop to clear the channel and allow the message to be heard. Mayday transmissions must always be acknowledged and immediate action taken. The IC must either personally handle the situation or designate another officer to do so. Part of "handling" a Mayday is to communicate with the fire fighter(s) in distress and with any other fire fighters or officers involved. The sooner the IC is notified and a RIT is activated, the greater the chance of the fire fighter being rescued. If there is any question that a Mayday may have been transmitted and heard by someone (not all), it should also receive priority in verifying if it were a Mayday transmission. The IC should be made aware of this immediately, so that he can attempt to contact the potential individual who transmitted the Mayday or contact dispatch to verify the transmission. A possible Mayday transmission should never be overlooked.

During this incident, the IC had to monitor two different radio channels by using two different handheld radios. His BA also assisted in monitoring the two radio channels. At times, radio transmissions on one channel were missed or unanswered because the IC was transmitting on the opposite channel. The DC and officer of E12 all thought they heard what sounded like a Mayday (transmitted from Victim #1), and a face to face discussion occurred among them and the IC, but this possible Mayday transmission was not confirmed with dispatch, nor, at the time, the unknown fire fighter that transmitted it.

This fire department had established a Mayday procedure within the department that was practiced routinely with the communications center, but this routine radio check did not test fire fighter or dispatcher competencies in the Mayday procedure, or the ability of an IC to manage a Mayday incident. Weekly, dispatch would select a company and radio channel to practice the Mayday procedure. The dispatchers followed a procedure at a scheduled day and time, instead of having an unannounced Mayday called. The challenge for fire departments is providing realistic, safe training that accurately simulates fire conditions, but it is absolutely necessary that the Mayday training place fire fighters in positions that closely simulate an actual fire to realistically exercise one's Mayday skills.17 In this incident, Mayday transmissions were missed and not acknowledged. It is not known why the dispatch center did not hear or acknowledge the Maydays or why the Mayday tone was not used appropriately.

Fire departments should be aware of the recently released 2010 International Association of Fire Chiefs' (IAFC) Rules of Engagement (ROE) of Structural Firefighting.18 These guidelines recommend that fire fighters constantly monitor fireground communications for critical radio reports and declare a Mayday as soon as they are in danger. Although not addressed by the IAFC ROE, ICs and dispatch centers should also be constantly monitoring fireground communications for critical radio reports.

Also, the IAFF Fire Ground Survival program was developed to ensure that training for Mayday prevention and Mayday operations are consistent between all fire fighters, company officers, and chief officers. 17

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that Mayday training program(s) and department procedures adequately prepare fire fighters to call a Mayday.