Timeline for Linking a Case of Listeria Infection to an Outbreak

Have you ever wondered why it takes a while to hear about cases of Listeria infection after a person gets sick? Or why the number of cases linked to an outbreak can increase for weeks after measures are taken to stop the outbreak?

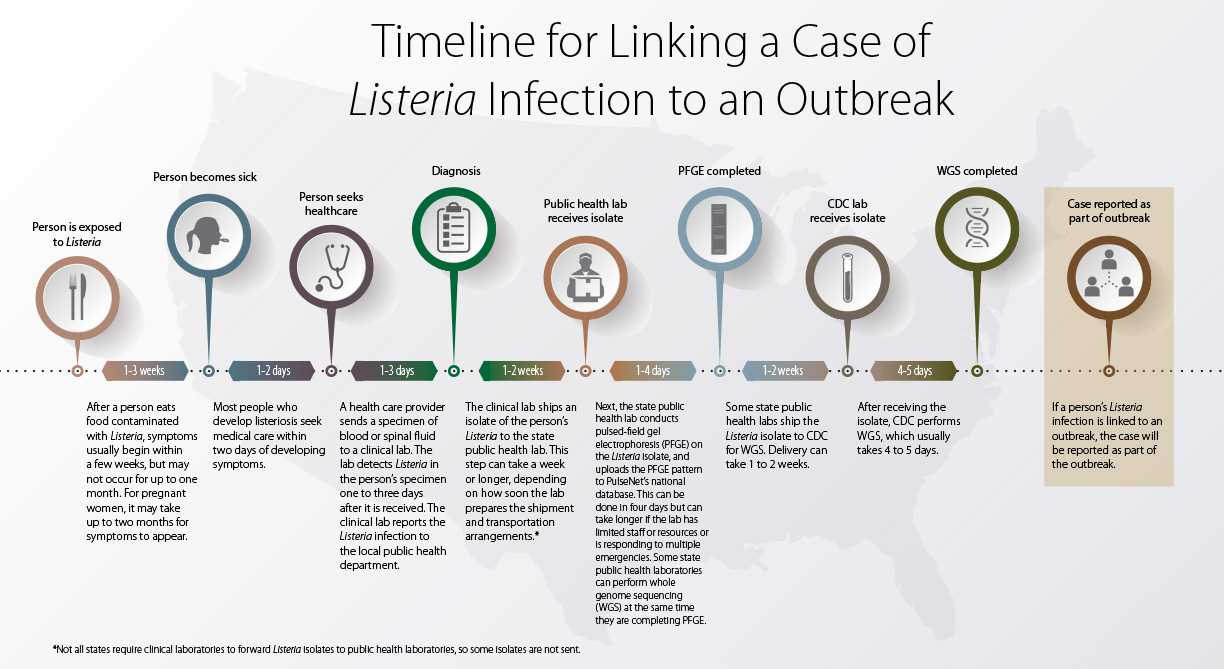

A series of events occurs from when someone eats a food contaminated with Listeria to when public health officials can determine that the person is part of an outbreak. This typically takes about 2–10 weeks but can take much longer. So the number of cases linked to an outbreak can continue to increase as more cases are found. Some of them may even have occurred years before.

The following factors contribute to the time it takes to recognize a case of Listeria infection (listeriosis) and report that it is part of an outbreak:

Time to illness (typically 1–3 weeks): After a person eats food contaminated with Listeria, symptoms usually begin within a few weeks, but may not occur for up to one month. For pregnant women, it may take up to two months for symptoms to appear.

Time to seek health care (typically 2 days): Most people who develop listeriosis seek medical care within two days of developing symptoms.

Time to diagnosis (typically 3 days): A health care provider examines the person and sends a specimen of blood or spinal fluid to a clinical lab. The lab detects Listeria in the person’s specimen one to three days after it is received. The clinical lab reports the Listeria infection to the local public health department.

Time to ship isolate to public health lab (typically 7 days): The clinical lab ships an isolate of the person’s Listeria to the state public health lab. This step can take a week or longer, depending on how soon the lab prepares the shipment and transportation arrangements.*

Time to complete pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (typically 4 days): Next, the state public health lab conducts pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) on the Listeria isolate, and uploads the PFGE pattern to PulseNet‘s national database. This can be done in four days but can take longer if the lab has limited staff or resources or is responding to multiple emergencies. Some state public health labs can perform whole genome sequencing (WGS) at the same time they are completing PFGE.

Time to ship to CDC lab (typically 1–2 weeks): Some state public health labs ship the Listeria isolate to CDC for WGS. Delivery can take 1 to 2 weeks.

Time to perform whole genome sequencing and analysis (typically 5 days): After receiving the isolate, CDC performs WGS, which usually takes 4 to 5 days.

Report case as part of outbreak: If a person’s Listeria infection is linked to an outbreak, the case will be reported as part of the outbreak.

*Not all states require clinical labs to forward Listeria isolates to public health labs, so some isolates are not sent.

Glossary

- Clinical lab: A lab that performs tests on patients’ specimens to help care providers diagnose and treat them

- Isolates: Actual living organisms, e.g., bacteria, obtained from an ill person’s specimen

- Public health lab: A local, state, or federal government lab that monitors and detects diseases and other threats to the public’s health

- Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE): A technique used to generate DNA fingerprints of bacteria

- PulseNet: the national molecular subtyping network of public health and food regulatory agency labs coordinated by CDC that identifies possible outbreaks

- Serotyping: a way of identifying specific types of bacteria

- Specimen: A sample (e.g., stool, blood, urine) collected from a patient for testing and diagnosis

- Whole genome sequencing (WGS): A process that determines an organism’s complete genetic composition and gives a more detailed DNA fingerprint than pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

Catching the Culprit

Bacteria with the same DNA fingerprint are more likely to be from the same source. Investigators determine whether the DNA fingerprint pattern of Listeria bacteria from one person is the same as that from other people.

Epidemiologists investigate clusters of people who have bacteria with the same DNA fingerprint to find out what they may have in common. Did they all eat the same food, or shop at the same type of market? To find out, investigators conduct extensive interviews, asking ill people or their caregivers about the foods they ate and where the foods were purchased and eaten. By analyzing the answers, they can sometimes identify a suspect food. Epidemiologists compare answers from people in the cluster with those of other people with Listeria not involved in the cluster. Investigators also may test suspect food. If they find the same type of bacteria that sickened people, they take DNA fingerprints from isolates cultured from the food bacteria, to see if it closely matches those of the ill people. When two or more people experience a similar illness from eating the same food, it is called an outbreak.

When a likely source is identified, public health officials take steps to control and stop the outbreak, such as working with companies to recall the food and warning people not to eat it.

- Page last reviewed: December 12, 2016

- Page last updated: December 12, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir