New and Underused Vaccines

Vaccine Surveillance & Introduction

The Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) was established by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1974 to provide protection against six vaccine-preventable diseases through routine infant immunization:

- tuberculosis

- poliomyelitis

- diphtheria

- tetanus

- pertussis

- measles

Since then, many new vaccines have become available and global public funding for immunization, including the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI Alliance), has increased accessibility to these vaccines.

Most of the new or underused vaccines, including hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), rotavirus (RV) vaccine, and rubella-containing vaccine, are intended to be included in the routine childhood immunization schedule. Other new or underused vaccines, such as cholera vaccine, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, meningococcal vaccine, yellow fever vaccine, and typhoid vaccine are intended for older or at-risk populations.

Cholera

Cholera is an acute, diarrheal illness caused by infection with the toxigenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139. The disease is transmitted through the fecal-oral route primarily through polluted water. Outbreaks occur most often in settings with poor water and sanitation infrastructure. An estimated 3 to 5 million cholera cases and more than 100,000 deaths occur each year around the world.

The infection is often mild or without symptoms, but can sometimes be severe. About 5% of infected persons will have severe disease characterized by excessive watery diarrhea, vomiting, and leg cramps. In these people, rapid loss of body fluids leads to dehydration and shock. Without treatment, death can occur within hours.

Rehydration treatment, provision of safe water, and adequate sanitation and hygiene remain the mainstay of cholera control and prevention efforts. Cholera vaccines are an additional tool until long-term improvements in water and sanitation infrastructure occur. Two oral cholera vaccines are currently available internationally:

- Dukoral® (manufactured by Crucell/SBL Vaccine, Sweden), and

- Shanchol™ (manufactured by Shantha Biotechnics/Sanofi, India)

Both vaccines are killed, whole-cell, two-dose vaccines.

CDC’s work related to cholera vaccines:

- Active membership in the Coalition for Cholera Prevention and Control.

- Read about our work with Oral Cholera Vaccination in Mae La Refugee Camp, Thailand “Inspiring Partnerships: Protecting Against Cholera in Thailand.”

- Collaborate to provide resources and information about the Haiti Cholera Outbreak.

Additional Cholera Resources:

- Read more about cholera

- Read about oral cholera vaccines

- Read the 2010 WHO Position Paper on Cholera Vaccines [PDF – 276KB]

- Recent Publications:

- Considerations for Oral Cholera Vaccine use During a Cholera Outbreak in an Emergency Setting and Lessons Learned, Post-Earthquake Haiti, 2010-2011

- Real-time Modelling Used for Outbreak Management During a Cholera Epidemic, Haiti, 2010-2011

- The Cure for Cholera – Improving Access to Safe Water and Sanitation

- Cholera Surveillance During the Haiti Epidemic – The First 2 Years

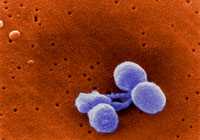

Haemophilus Influenzae Type B (Hib)

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease is a leading cause of childhood bacterial meningitis, pneumonia, and other serious infections. Hib vaccines are safe and work well even when given in early infancy. The vaccine is included in routine childhood vaccination programs in more than 184 countries in all regions of the world.

As a result, invasive Hib disease has been practically eliminated in many industrialized countries, and its incidence has been dramatically reduced in some parts of the developing world. WHO recommends the use of Hib vaccines in all routine infant immunization programs.

CDC’s work related to Hib vaccines:

- Participate in post-introduction evaluations of Hib vaccination in Bosnia and Herzegovina, India, Nigeria, and Ukraine.

- Strengthen disease surveillance and response in Central Africa – Le Projet de Renforcement de la Surveillance en Afrique Centrale (SURVAC).

- Provide technical support for surveillance and evaluations of vaccine impact/effectiveness in several locations including Mongolia, Ukraine, Mozambique, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Chile, Colombia, Uruguay, Argentina, Eastern Mediterranean region.

Additional Hib Resources:

- Read more about Hib disease

- Read about Hib vaccines

- Read the 2006 WHO Position Paper on Haemophilus influenza type b conjugate vaccines [PDF – 206KB]

- Hib vaccine introduction maps

- Recent Publications:

- Watch the Hib Initiative video series

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). It ranges in severity from a mild illness, lasting a few weeks (acute), to a serious long-term (chronic) illness that can lead to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

HBV is transmitted by percutaneous (i.e., puncture through the skin) or mucosal (i.e., direct contact with mucous membranes) exposure with infectious blood and other body fluids. The major, global routes of transmission are from mother to infant (perinatal), child to child (non-sexual person to person contact), sexual contact, and percutaneous exposure to blood or other infectious body fluids.

The World Health Organization recommends hepatitis B vaccination for all infants beginning at birth, as part of the routine childhood vaccination schedule in all countries. Recommendations for catch-up vaccination of older age groups vary by country based on the epidemiology of each region’s infection and disease rates.

CDC’s work to prevent hepatitis B

CDC provides both scientific and technical support to partners and countries in other parts of the world to decrease the burden of hepatitis B infection.

Documenting the magnitude of the problem

- Conduct surveys to evaluate the prevalence of hepatitis B among children in the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Haiti, Solomon Islands, and Tajikistan

- Conduct surveys to assess the burden of hepatitis B in pregnant women in Haiti to guide vaccination policy

- Assess the burden of hepatitis B in Afghanistan to determine if birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine should be introduced

- Assess the burden of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B in Africa to inform hepatitis B vaccine birth dose introduction

Diagnostics

- Assess whether or not hepatitis B can be detected through saliva (oral fluids)

- Assessing whether or not rapid field testing methods are accurate compared to the gold standard ELISA lab-based testing

Improving coverage of hepatitis B vaccine birth dose

- Pilot to evaluate best practices for using hepatitis B vaccine in a controlled temperature chain in rural Lao PDR, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands; plan to scale up in 2017-2019

- Pilot to evaluate the impact of providing cell phones to village health volunteers to improve timely reporting of new home births and its impact on birth dose administration in Lao PDR

- Evaluating and improving birth dose implementation in health facilities in Cambodia, Lao PDR, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea

- Evaluating selective hepatitis B birth dose vaccination in Sao Tome and Principe: a program assessment and cost-effectiveness study

- Contribute to the Global hepatitis B birth dose introduction guidelines

Evaluating the impact of hepatitis B vaccines after introduction

- Implement serosurveys in Bangladesh, Cambodia, the Philippines, South Pacific Islands (French Polynesia, Cook Islands, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Kiribati, Niue, Nauru), Papua New Guinea, and Oman to document the impact of hepatitis B vaccine and progress of countries to reach the hepatitis B control/elimination goal

- Implement a two-stage survey to verify the achievement of hepatitis B elimination in Colombia

- Assisting GAVI Alliance with estimating lives saved because of hepatitis B vaccine

Additional Hepatitis B Resources:

- Read more about Hepatitis B

- Read about Hepatitis B vaccines

- Read the 2017 WHO Position paper on Hepatitis B Vaccines

- Read the Global Hepatitis Report, 2017

- Read the Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016-2021

- Hepatitis B coverage in 2015 map

- Recent Publications:

- The Status of Hepatitis B Control in the African Region

- Hepatitis B Vaccine Birth Dose Coverage Correlates Worldwide with Rates of Institutional Deliveries and Skilled Attendance at Birth

- Improving hepatitis B birth dose coverage through village health volunteer training and pregnant women education

- Evaluation of storing hepatitis B vaccine outside the cold chain in the Solomon Islands: identifying opportunities and barriers to implementation

- Hepatitis B Virus Infection among Pregnant Women in Haiti: a Cross-Sectional Serosurvey

- Improving hepatitis B birth dose in rural Lao People’s Democratic Republic through the use of mobile phones to facilitate communication

- Progress towards achieving hepatitis B control in the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, and Kiribati

- Hepatitis B vaccine stored outside the cold chain setting: a pilot study in rural Lao PDR

- Hepatitis B Vaccination Coverage and Prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Among Children in French Polynesia, 2014

- Check out the World Hepatitis Alliance website for more resources

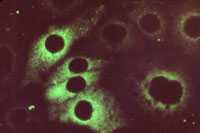

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI). There are more than 40 HPV types that can infect the genital areas of males and females. These HPV types can also infect the mouth and throat. HPV is passed through genital contact, most often during vaginal and anal sex. HPV may also be passed during oral sex and genital-to-genital contact between straight and same-sex partners—even when the infected person has no signs or symptoms. Most people with HPV never develop symptoms or health problems.

Most HPV infections (90%) resolve within two years. However, some HPV infections persist and can cause a variety of serious health problems, including:

- cervical cancer,

- genital warts,

- recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (a rare condition in which warts grow in the throat), and

- other types of genital and oropharyngeal cancers.

HPV is the main cause of cervical cancer in women. Each year, nearly 530,000 women contract cervical cancer and 275,000 die from it; a disproportionate number of these deaths occur in developing countries.

Currently, two HPV vaccines are available internationally – Cervarix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Gardasil (Merck). HPV vaccines are given as a series of three shots over 6 months. Both vaccines protect against cervical cancers caused by HPV types 16 and 18 in women. One vaccine, Gardasil, also protects against genital warts caused by HPV types 6 and 11, and has also been shown to prevent cancers of the anus, vagina, and vulva caused by HPV 16 and 18. Both vaccines are available for females. Gardasil is also available for males in some countries. HPV vaccines offer the best protection to girls and boys who receive all three vaccine doses and have time to develop an immune response before being sexually active with another person. WHO recommends HPV vaccination for girls 9 to 13 years old.

CDC’s work related to HPV vaccines:

- Technically assist countries and partners including WHO and GAVI Alliance for planning and implementation of HPV vaccination programs and cervical cancer screening programs

- Evaluate HPV vaccine attitudes, practices in Kenya, 2012

- Evaluate HPV vaccine introduction in Latvia 2012

Additional HPV Resources:

- Read the 2009 WHO Position Paper on HPV vaccines [PDF – 261KB]

- Recent Publications:

- HPV Vaccine Communication: Special considerations for a unique vaccine [PDF – 4.01MB]

- Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescent Girls, 2007–2012, and Postlicensure Vaccine Safety Monitoring, 2006–2013 — United States

- Reduction in human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence among young women following HPV vaccine introduction in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2003-2010

- Monitoring HPV vaccine impact: Early results and ongoing challenges

- Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Introduction – The First Five Years

- Visit the HPV Vaccine Introduction Clearinghouse for resources on HPV vaccine introduction

- Check out the GAVI HPV infographic

Japanese Encephalitis

Japanese encephalitis (JE) virus is the leading vaccine-preventable cause of encephalitis in Asia, causing an estimated 67,900 cases yearly. JE is a mosquito-borne disease with a 20 to 30% case-fatality rate and neurologic or psychiatric sequelae in 30 to 50% of survivors.

Several types of JE vaccine are used globally. These include:

- inactivated mouse brain–derived vaccine,

- inactivated Vero cell culture-derived vaccines,

- live attenuated vaccine based on the SA 14-14-2 JE virus strain, and

- live attenuated chimeric vaccine.

CDC’s work related to JE vaccines:

- Assist the Cambodian Ministry of Health to evaluate the impact on meningoencephalitis of a vaccination campaign using live attenuated SA 14-14-2 JE vaccine.

- Provide technical assistance for JE surveillance to the International Center for Diarrhoeal Disease Research (ICDDR, b) and the Government of Bangladesh.

Additional Japanese Encephalitis Resources:

- Read more about Japanese encephalitis (JE)

- Read about JE vaccines available in the United States

- Read the 2006 WHO Position Paper on JE vaccines [PDF – 196KB]

- Recent Publications:

- JE surveillance and immunization – Asia and the Western Pacific, 2012

- Estimation of the impact of a Japanese encephalitis immunization program with live, attenuated SA 14-14-2 vaccine in Nepal

- Expanding poliomyelitis and measles surveillance networks to establish surveillance for acute meningitis and encephalitis syndromes–Bangladesh, China, and India, 2006-2008

- Estimated global incidence of Japanese encephalitis: a systematic review

Serogroup A Meningococcal Disease

Since the introduction of H. influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccines, N. meningitidis and S. pneumoniae have become the most common causes of bacterial meningitis in the world. N. meningitidis serogroup A causes large epidemics in developing countries, specifically in the countries of the African ‘meningitis belt.’

A meningococcal A (MenA) conjugate vaccine, intended for use mainly in the African ‘meningitis belt,’ was licensed in 2010. By the end of 2012, more than 100 million people in Africa had been vaccinated against serogroup A meningococcal disease.

CDC’s work related to serogroup A meningococcal vaccines:

- Strengthen disease surveillance and response in Central Africa – Le Projet de Renforcement de la Surveillance en Afrique Centrale (SURVAC).

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Grant: “MenAfriNet: A regional meningitis surveillance network to evaluate the impact of MenAfriVac introduction in the African Meningitis Belt”

- Learn more through this article about the Division of Bacterial Disease’s Work to Eliminate Epidemic Meningitis Continues: Staff Activities in Ethiopia

- Learn more through this article about Working to Eliminate Epidemic Meningitis in Sub-Saharan Africa

Additional Serogroup A Meningococcal Disease Resources:

- Read more about serogroup A meningococcal disease

- Learn about the Meningitis Vaccine Project

- Read the 2011 WHO Position Paper on meningococcal vaccines [PDF – 985KB]

- Meningitis A vaccine introduction map

- Recent Publications:

- Li Y, Yin Z, Shao Z, Li M, Liang X, Sandhu HS, Hadler SC, Li J, Sun Y, Li J, Zou W, Lin M, Zuo S, Mayer LW, Novak RT, Zhu B, Xu L, Luo H; Acute Meningitis and Encephalitis Syndrome Study Group. Population-based surveillance for bacterial meningitis in China, September 2006-December 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Jan;20(1):61-9

- Priorities for research on meningococcal disease and the impact of serogroup A vaccination in the African meningitis belt

- Serogroup A meningococcal conjugate vaccination in Burkina Faso: analysis of national surveillance data

- Impact of the serogroup A meningococcal conjugate vaccine, MenAfriVac, on carriage and herd immunity

- Evaluation of meningitis surveillance before introduction of serogroup a meningococcal conjugate vaccine – Burkina Faso and Mali

- Serogroup A meningococcal conjugate vaccine coverage after the first national mass immunization campaign-Burkina Faso, 2011

- Effect of a serogroup A meningococcal conjugate vaccine (PsA–TT) on serogroup A meningococcal meningitis and carriage in Chad: a community study

- CDC infographic: Meningitis A is deadly, expensive and preventable

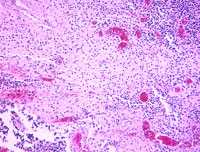

Pneumococcus

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the bacterium responsible for pneumococcal disease, a leading cause of childhood pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis. Worldwide, an estimated 14.5 million episodes of serious pneumococcal disease occur each year among children under 5 years of age, resulting in approximately 500,000 deaths, most of which occur in low and middle-income countries.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) can provide protection against pneumococcal disease. The World Health Organization recommends PCV be included in every country’s national immunization program, especially in countries with high pneumococcal disease burden.

CDC’s work related to pneumococcal vaccines:

- Participate in post-introduction evaluation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Ghana and Kenya.

- Strengthen disease surveillance and response in Central Africa – Le Projet de Renforcement de la Surveillance en Afrique Centrale (SURVAC).

- Technical support for surveillance and evaluations of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine impact/effectiveness in several locations including Haiti, Colombia, Brazil, Uruguay, Dominican Republic, South Africa, Mozambique, Malawi, Kenya, Burkina Faso, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

- CDC Streptococcal laboratory serves as the global reference laboratory for World Health Organization Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network

Additional Pneumococcus Resources:

- Read more about pneumococcal disease

- Read about pneumococcal vaccines

- Read the 2012 WHO Position Paper on pneumococcal vaccines [PDF – 1MB]

- Recent Publications:

- Progress in introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine – worldwide, 2000-2012

- Effectiveness of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against vaccine-type invasive disease among children in Uruguay: an evaluation using existing data

- Effect of 10-valent pneumococcal vaccine on pneumonia among children, Brazil

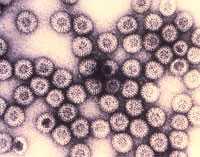

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is the leading cause of severe diarrhea among infants and young children worldwide. Before rotavirus vaccines were available, almost all children were infected with rotavirus, regardless of where they lived.

The World Health Organization recommends that rotavirus vaccine be included in every country’s national immunization program. Since 2006, more than 40 countries have introduced rotavirus vaccines into their national immunization programs. Many countries have since documented substantial declines in rotavirus disease burden in both vaccinated and unvaccinated children.

CDC’s work related to rotavirus vaccines:

- Participate in post-introduction evaluations of rotavirus vaccine (past evaluations in Armenia, Ghana, Moldova, Rwanda, and Tanzania).

- Conduct surveillance and vaccine impact evaluations in many countries including Armenia, Moldova, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Nicaragua, Ghana, Malawi, Rwanda, and South Africa.

- Strengthen disease surveillance and response in Central Africa – Le Projet de Renforcement de la Surveillance en Afrique Centrale (SURVAC).

Additional Rotavirus Resources:

- Read more about rotavirus

- Read about rotavirus vaccines

- Read the 2013 WHO Position Paper on rotavirus vaccines [PDF – 409KB]

- Learn about the Rotavirus Vaccine Program

- Recent Publications:

- Pukuta ES, Esona MD, Nkongolo A, Seheri M, Makasi M, Nyembwe M, Mondonge V, Dahl BA, Mphahlele MJ, Cavallaro K, Gentsch J, Bowen MD, Waku-Kouomou D, Muyembe JJ; SURVAC Working Group. Molecular surveillance of rotavirus infection in the Democratic Republic of the Congo August 2009 to June 2012. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Apr;33(4):355-9.

- Yen C, Tate JE, Hyde TB, Cortese MM, Lopman BA, Jiang B, Glass RI, Parashar UD. Rotavirus vaccines: Current status and future considerations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014 Apr 22;10(6).

- Building rotavirus laboratory capacity to support the Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network

- Effect of rotavirus vaccine on diarrhea mortality in different socioeconomic regions of Mexico

- Fulfilling the promise of rotavirus vaccines: how far have we come since licensure?

- 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- WHO Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network: A Strategic Review of the First 5 Years, 2008–2012

- Check out the ROTA Council website for more technical resources

Rubella

Rubella is usually a mild, self-limited infection causing fever and rash in children and adults. Rubella’s public health importance is due to the potential of the virus to cause malformations of an embryo or fetus in infected pregnant women, especially during the first trimester of pregnancy. Infection can result in poor pregnancy outcomes, including miscarriage, fetal death, or infants born with congenital malformations, known as Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS). More than 100,000 infants with CRS are born each year. A safe and effective vaccine was introduced in 1969, but has not been introduced in all countries.CDC’s work related to rubella vaccines:

- Provide expertise to WHO and other immunization partners to develop global policies to improve the control of rubella and prevent CRS.

- Establish and strengthen CRS surveillance systems and sero-surveys to support countries collecting and analyzing the burden of rubella and CRS.

- Conduct research, including modeling and economic studies.

- Develop plans for

- Introducing the rubella vaccine at the global, regional, and country levels,

- monitoring the program,

- establishing and strengthening both rubella and CRS surveillance systems,

- documenting the elimination of the rubella/CRS, and

- assisting in maintaining elimination.

Additional Rubella Resources:

- Read more about rubella

- Read about rubella vaccines

- Read the 2011 WHO Position Paper on rubella vaccines [PDF – 357KB]

- Countries using rubella vaccine in national schedule, 2012

- Recent Publications:

- Check out the Measles & Rubella Initiative for more technical resources

- CDC infographic: Stop Rubella

Typhoid

Typhoid fever (typhoid) is a severe, systemic infection caused by the bacterium Salmonella Typhi (S. Typhi). It causes an estimated 21 million cases and 216,000 to 600,000 deaths worldwide each year. The infection is transmitted through the fecal-oral route from acutely infected individuals or from recovering or chronic carriers. The majority of typhoid cases and deaths occur among populations that lack access to drinkable water, adequate sanitation, and hygienic facilities – primarily in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Typhoid is clinically difficult to tell apart from many other illness caused by fever, including paratyphoid fever, dengue, malaria, and leptospirosis, which may also be widespread or cause epidemics in the same geographic areas.

Ensuring safe water, adequate sanitation, and improved hygiene are the definitive measures for typhoid fever prevention and control. Typhoid vaccines are an additional complementary tool. The WHO recommends use of typhoid fever vaccination in endemic areas and for outbreak control. Two typhoid vaccines are licensed and available in many countries:

- the Ty21a vaccine, which is an oral, live, attenuated vaccine, and

- the Vi polysaccharide vaccine, which is a subunit, injectable, single dose vaccine and is licensed for persons 2 years and older.

Several newer typhoid conjugate vaccines, which can be incorporated into the routine infant immunization schedule, are in different stages of development. One has recently been launched in India.

CDC’s work related to typhoid vaccines:

- Active member of the Coalition Against Typhoid.

- Evaluation of the impact of a mass typhoid fever vaccination campaign, Fiji 2011.

- Investigate typhoid fever outbreak and response in several countries, including Malawi, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

- Conduct initial studies of vaccine acceptability in Malawi and Uganda.

- Technically assist countries with laboratory services and trainings for blood culture and rapid typhoid detection tests.

- Serve as co-investigators for the multi-country project – Typhoid fever surveillance in Africa (TSAP).

Additional Typhoid Resources:

- Read more about typhoid fever

- Read about typhoid vaccines

- Read the 2008 WHO Position Paper on typhoid vaccines [PDF – 131KB]

- Global burden of typhoid map

- Recent Publications:

- Scobie HM, Nilles E, Kama M, Kool JL, Mintz E, Wannemuehler KA, Hyde TB, Dawainavesi A, Singh S, Korovou S, Jenkins K, Date K. Impact of a Targeted Typhoid Vaccination Campaign Following Cyclone Tomas, Republic of Fiji, 2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014 Apr 7. [Epub ahead of print ]

- Vaccination for typhoid fever in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Population-based incidence of typhoid fever in an urban informal settlement and a rural area in Kenya: implications for typhoid vaccine use in Africa

- Multidrug-resistant typhoid fever with neurologic findings on the Malawi-Mozambique border

- A large outbreak of typhoid fever associated with a high rate of intestinal perforation in Kasese District, Uganda, 2008-2009

- Check out the Coalition Against Typhoid for more technical resources.

Yellow Fever

Yellow fever is a mosquito-borne disease that is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa and tropical South America. Yellow fever virus is estimated to cause 200,000 cases of disease and 30,000 deaths each year, with 90% occurring in Africa.

Yellow fever varies from a mild, undifferentiated illness with fever, to severe disease with jaundice and hemorrhage or severe bleeding. Twenty to 50% of persons with the severe disease die.

All currently available yellow fever vaccines are live-attenuated vaccines that use the 17D strain. Studies comparing the various vaccines show no difference in the side effects or immune responses generated by these vaccines.

CDC’s work related to yellow fever vaccines:

- Help the World Health Organization assess yellow fever virus activity in selected African countries and implement protocols related to yellow fever vaccine immunity and safety.

- Provide technical assistance to the GAVI-sponsored Yellow Fever Initiative that aims to reduce the risk of yellow fever epidemics by improving vaccination coverage in higher risk countries.

Additional Yellow Fever Resources:

- Read more about yellow fever

- Read about yellow fever vaccines

- Read the 2013 WHO Position Paper on yellow fever vaccines [PDF – 162KB]

- Maps showing geographic distribution of yellow fever in South America and Africa

- Recent Publications:

- Yellow fever in Africa and South America, 2011-2012 [PDF – 62KB]

- Viscerotropic disease: Case definition and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data

- The revised global yellow fever risk map and recommendations for vaccination, 2010: consensus of the Informal WHO Working Group on Geographic Risk for Yellow Fever

- Page last reviewed: July 20, 2017

- Page last updated: July 20, 2017

- Content source:

Global Health

Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir