Highlights from the 2015 Surveillance Report

When two or more people become ill from consuming the same contaminated food or drink, the event is called a foodborne disease outbreak. Outbreaks provide important insights into how germs are spread, which food and germ combinations make people sick, and how to prevent food poisoning. Each year, CDC summarizes foodborne disease outbreak data in an annual surveillance report and makes it available to the public through the FOOD Tool.

Main Findings

In 2015, 902 foodborne disease outbreaks were reported, resulting in 15,202 illnesses, 950 hospitalizations, 15 deaths, and 20 food recalls.

- Single food categories associated with the most outbreak illnesses:

- Seeded vegetables, such as cucumbers or tomatoes (1,121 illnesses)

- Pork (924 illnesses)

- Vegetable row crops, such as leafy vegetables (383 illnesses)

- Single food categories associated with the most outbreaks:

- Fish (34 outbreaks)

- Chicken (22 outbreaks)

- Pork (19 outbreaks)

- Restaurants (469 outbreaks, 60% of outbreaks reporting a single location of preparation), specifically restaurants with sit-down dining (373, 48%), were the most commonly reported locations of food preparation.

- There were 30 multistate outbreaks, including the following types of foods linked to them:

- Vegetable row crops (4 outbreaks)

- Seeded vegetables (3 outbreaks)

- Grains, such as flour (2 outbreaks)

- Herbs (2 outbreaks)

- Mollusks (2 outbreaks)

Other Highlights

Germs

A single, confirmed agent or germ caused 443 outbreaks. The most commonly reported were:

- Norovirus (37% of the outbreaks)

- Salmonella (34% of the outbreaks)

A single, confirmed germ caused 10,008 outbreak-related illnesses and 896 hospitalizations (about 1 of every 11 illnesses). The most common causes:

- Norovirus (37% of the outbreaks and 39% of the illnesses)

- Salmonella (34% of the outbreaks and 39% of the illnesses)

- Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (6% of the outbreaks and 3% of the illnesses)

The agents that caused the most outbreak-related hospitalizations were:

- Salmonella (573 hospitalizations, 64% of outbreak-related hospitalizations)

- Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (106 hospitalizations,12% of outbreak-related hospitalizations)

- Shigella (53 hospitalizations, 6% of outbreak-related hospitalizations)

The agents that caused outbreak-related deaths were:

- Salmonella (9 deaths)

- Clostridium botulinum (2 deaths)

- Clostridium perfringens (1 death)

- Listeria monocytogenes (1 death)

- Norovirus (1 death)

- Vibrio vulnificus (1 death)

Foods

For 40% of the outbreaks in 2015 (360 outbreaks), investigators were able to identify the food that made people ill. The food could be placed into a single category, out of 24 possible categories, in 194 of those outbreaks, or slightly more than half of them. The most commonly implicated food categories were:

- Fish (34 outbreaks, 18% of the outbreaks)

- Chicken (22 outbreaks, 11% of the outbreaks)

- Pork (19 outbreaks, 10% of the outbreaks)

- Dairy (18 outbreaks, 9% of the outbreaks)

- Pasteurization information was reported for 14 of the dairy outbreaks

- Thirteen of those outbreaks (93%) involved unpasteurized products

Outbreaks in which the food could be classified into a category included 4,364 illnesses. Outbreak-associated illnesses were most commonly from:

- Seeded vegetables, such as cucumbers or tomatoes (1,121 illnesses, 26% of the illnesses)

- Pork (924 illnesses, 21% of the illnesses)

- Vegetable row crops, such as leafy vegetables (383 illnesses, 9% of the illnesses)

- Chicken (333 illnesses, 8% of the illnesses)

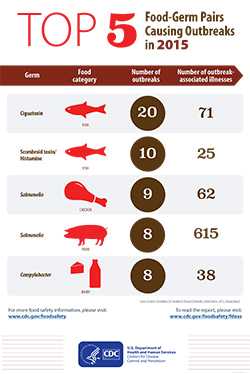

Combinations of Foods and Germs that Caused Illnesses, Hospitalizations, and Deaths

Knowing which food and germ combinations make people sick is critically important to preventing future foodborne outbreaks. The confirmed germ-food pairs responsible for the most outbreak were:

-

Illnesses

- Salmonella in seeded vegetables (1,048 illnesses)

- Salmonella in pork (615 illnesses)

- Salmonella in vegetable row crops (263 illnesses)

-

Hospitalizations

- Salmonella in seeded vegetables (225 hospitalizations)

- Salmonella in pork (70 hospitalizations)

- Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin in chicken (31 hospitalizations)

-

Deaths

- Salmonella in seeded vegetables (6 deaths)

- Clostridium botulinum in root and other underground vegetables (2 deaths)

- Clostridium perfringens in beef (1 death)

- Listeria monocytogenes in vegetable row crops (1 death)

- Salmonella in pork (1 death)

- Salmonella in sprouts (1 death)

- Vibrio vulnificus in mollusks (1 death)

The confirmed germ-food pairs responsible for the most outbreaks were:

- Ciguatoxin in fish (20 outbreaks)

- Scombroid toxin (histamine poisoning) in fish (10 outbreaks)

- Salmonella in chicken (9 outbreaks)

Settings

Among the 779 outbreaks and 12,054 illnesses with a reported single location where food was prepared, 469 outbreaks (60%) and 4,757 associated illnesses (39%) were attributed to foods prepared in a restaurant.

Among these outbreaks, sit-down dining restaurants were the type most commonly reported as the location where food was prepared (373 outbreaks, 48% of the outbreaks).

Recalls

Product recalls occurred in 20 outbreaks:

- Chicken (2 outbreaks)

- Pork (2 outbreaks)

- Raw tuna (2 outbreaks)

- Alfalfa seeds and sprouts (1 outbreak)

- Apple cider (1 outbreak)

- Bread (1 outbreak)

- Celery (1 outbreak)

- Cucumber (1 outbreak)

- Drink mix (1 outbreak)

- Milkshakes (1 outbreak)

- Flour (1 outbreak)

- Ground beef (1 outbreak)

- Lettuce (1 outbreak)

- Moringa leaf powder (1 outbreak)

- Muffins (1 outbreak)

- Roast beef (1 outbreak)

- Sprouted nut butter (1 outbreak)

- Unpasteurized milk (1 outbreak)

Outbreaks in Multiple U.S. States

In 2015, there were 30 multistate outbreaks (3% of all reported outbreaks), resulting in 1,947 illnesses (12% of illnesses), 411 hospitalizations (42% of hospitalizations), and 7 deaths (50% of deaths).

Germs responsible for multistate outbreaks:

- Salmonella (17 outbreaks)

- Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (10 outbreaks)

- Cyclospora cayetanensis (1 outbreak)

- Listeria (1 outbreak)

- Vibrio parahaemolyticus (1 outbreak)

Foods implicated or suspected in multistate outbreaks of Salmonella:

- Tomatoes (2 outbreaks)

- Tuna sushi (1 confirmed, 1 suspected; 2 outbreaks total)

- Alfalfa seeds and sprouts (1 outbreak)

- Chicken (1 outbreak)

- Cucumber (1 outbreak)

- Latin-style soft cheese (suspected; 1 outbreak)

- Moringa leaf powder (1 outbreak)

- Pork (1 outbreak)

- Raw oysters (suspected; 1 outbreak)

- Raw tuna (1 outbreak)

- Sprouted nut butter (1 outbreak)

- Sushi (suspected; 1 outbreak)

- Truffle oil puree (1 outbreak)

- Unidentified food (1 outbreak)

Foods implicated or suspected in multistate outbreaks of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli:

- Celery and onion (1 outbreak) (serogroup O157)

- Flour (1 outbreak) (serogroups O26 and O121)

- Pizza dough mix (suspected; 1 outbreak) (serogroup O157)

- Pre-packaged leafy greens (suspected; 1 outbreak) (serogroup O145)

- Pre-packaged salad (suspected; 1 outbreak) (serogroup O157)

- Romaine lettuce (suspected; 1 outbreak) (serogroup O157)

- Unidentified foods (serogroups O103 [2 outbreaks] and O26 [2 outbreaks])

Food implicated in a multistate outbreak of Cyclospora cayetanensis:

- Cilantro (1 outbreak)

Foods implicated in a multistate outbreak of Listeria:

- Lettuce (1 outbreak)

Foods implicated in a multistate outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus:

- Raw oysters and clams (1 outbreak)

Four multistate outbreaks investigated in 2015 are not included in the 2015 tally because the first outbreak-associated illness occurred before 2015. Three were caused by Listeria; the implicated foods were ice cream (first illness in 2010), caramel apples (first illness in 2014), and cheese made with pasteurized milk (first illness in 2014). One was caused by Salmonella; the implicated food was cashews (first illness in 2014).

More Information

Why is this report important?

Foodborne diseases due to known pathogens are estimated to cause about 9.4 million illnesses each year in the United States. Even though only a small proportion of these illnesses occur as part of a recognized outbreak, the data collected during outbreak investigations provide insights into the pathogens and foods that cause illness. Public health officials, regulatory agencies, and the food industry can use these data to create control strategies along the farm-to-table continuum that target specific pathogens and foods.

What else do I need to know about this year’s report?

The data from this report come from CDC’s Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System (FDOSS). State, local, and territorial health departments report the results of foodborne disease outbreak investigations to this system, and CDC provides an annual summary of outbreak investigations.

When comparing data between years, it is important to note that changes were made to this surveillance system in 2009, and a new food categorization scheme was implemented in 2011.

The findings in this report have at least three limitations. First, only a small proportion of foodborne illnesses that occur each year are identified as being associated with outbreaks. The extent to which the distribution of food vehicles and locations of preparation implicated in outbreaks reflect the same vehicles and locations as foodborne illnesses not associated with outbreaks is unknown. Similarly, not all outbreaks are identified, investigated, or reported. Second, many outbreaks had an unknown etiology (cause), an unknown food vehicle, or both, and may not be well represented by those outbreaks in which a food vehicle or etiology could be identified. Finally, CDC’s outbreak surveillance system is dynamic. Agencies can submit new reports and change or delete reports as information becomes available. Therefore, the results of this analysis might differ from those in other reports.

How can I learn how many reported outbreaks were associated with a certain food, germ, or setting?

Foodborne Outbreak Online Database (FOOD Tool) is a web-based program you can use to search CDC’s Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System database. FOOD Tool lets users search foodborne disease data by year, state, food and ingredient, location where food was prepared, and cause. It provides information on numbers of illnesses, hospitalizations, deaths, the germ, and the confirmed or suspected cause.

For guidance on using the data and limitations to keep in mind when searching by food or ingredient, take a look at frequently asked questions about FOOD Tool.

How can I find out about foodborne disease outbreak trends?

Surveillance for Foodborne Disease Outbreaks – United States, 1998-2008 describes 11 years of data about the causes of outbreaks and where they occur; the pathogens and foods that caused the most outbreaks, illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths; and trends in the pathogens and foods associated with outbreaks over time. Learn more >

What factors influence outbreak investigation and reporting?

Although foodborne disease outbreaks are a nationally notifiable condition, many factors can influence outbreak investigation and reporting, including available resources (such as time, staff, and laboratory capacity), health department priorities, and the characteristics of an outbreak (such as its size and severity).

Why is the cause of so many reported outbreaks unknown?

Even well-conducted investigations may not be able to identify the cause of an outbreak. Several factors influence whether investigators can identify the cause of an outbreak, including the timing of when a specimen is obtained.

- Infections are often diagnosed using specific laboratory tests that can identify bacteria, chemical agents and toxins, parasites, and viruses. When an outbreak isn’t identified until after the optimal time to obtain specimens from ill people, it may not be possible to obtain specimens for laboratory analysis or the laboratory tests may be negative.

- When timely specimens are obtained, other factors can lead to the cause not being detected. For example, clinical laboratories may not have the resources needed to identify some germs. In these outbreaks, the state public health laboratory or CDC may perform additional tests to try to identify the germ.

Even if the cause is not identified, CDC encourages states to report all foodborne disease outbreak investigations.

Why is the food unknown for so many reported outbreaks?

Even the most thorough investigations can fail to identify the contaminated food under certain circumstances, such as when most of the people who became sick ate many of the same foods (making it hard to identify the one that caused them to become ill), the number of people ill is very small, or the outbreak is identified after people’s memories of what they ate before getting sick have faded. CDC encourages health departments to report all foodborne outbreak investigations. Even if the contaminated food is not determined, we can learn useful information that can help shape prevention efforts.

Learn More About Foodborne Outbreaks

- Page last reviewed: May 31, 2017

- Page last updated: July 7, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir