PulseNet & Foodborne Disease Outbreak Detection

PulseNet connects similar cases of foodborne illness together, quickly finding outbreaks, and linking these illnesses across states and countries.

PulseNet connects similar cases of foodborne illness together, quickly finding outbreaks, and linking these illnesses across states and countries.

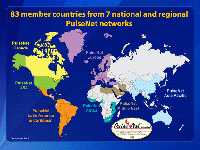

Since 1996, PulseNet has connected foodborne illness cases together, using DNA “fingerprinting” of the bacteria making people sick, to detect and define outbreaks. PulseNet has been responsible for detection of hundreds of local and multi-state outbreaks, leading to prevention opportunities and continuous improvements in our food safety systems that might not otherwise have occurred. Since “foodborne illnesses do not respect any borders,” PulseNet International performs a similar role for worldwide foodborne illnesses.

How Does PulseNet Work?

Pulse Net was developed after the 1993 E. coli O157 outbreak from hamburgers made 732 people sick and killed 4 children1. After the outbreak, more clinical labs began testing ill people for E. coli and found many more infections—revealing the problem was more serious than originally thought. Health departments did not have subtype data to help determine which illnesses were linked by a common food source.

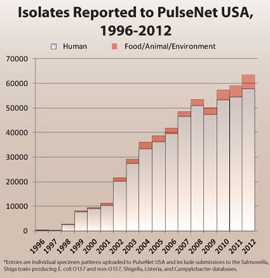

PulseNet solved this problem by providing the testing methods, technology, and subtype data needed to connect illnesses to a common food source. PulseNet is a national network of public health and food regulatory agency laboratories that perform standardized molecular subtyping (“fingerprinting”) of foodborne disease-causing bacteria. PulseNet detects subtypes of not only E. coli O157 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, but also the following bacteria: Campylobacter jejuni, Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium botulinum, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Yersinia pestis. From 1996 to 2012, individual annual human illness specimens (isolated pathogens from human samples submitted to laboratories by physicians) to PulseNet USA increased over 200-fold, and specimens from food, the environment, and other sources increased over 800-fold.

PulseNet tracks what is being reported to CDC today compared to what was reported in the past to look for changes. This means that PulseNet tracks a cumulative database representing nearly over one half a million isolates of bacteria from food, the environment, and human foodborne illness since 1996.

Today, PulseNet’s national laboratory network is made up of 87 laboratories−at least one in each state and many states include federal and local laboratories. Every state has at least one public health laboratory with the capacity to match up bacteria from sick people in many places, using PulseNet’s DNA fingerprinting technique and database. For example, public health laboratories can help quickly find an outbreak by revealing matching patterns among the approximately 750 Listeria illnesses that occur each year. It can also link illnesses in many different states, since all states are part of PulseNet.

During the recent mulitistate outbreak of Listeriosis linked to whole cantaloupes from Jensen Farms, Colorado,PulseNet public health laboratories rapidly identified the outbreak strains in Colorado patients, and then connected them with illnesses in 25 other states. This meant that Colorado helped other states see whether they had cases. In Colorado this was fast — it took only 7 days from when someone got sick to get their Listeria DNA fingerprints into the PulseNet database. In other states it took an average 17 days. Fingerprinting quickly meant people who were part of the outbreak were identified quickly. It also showed the same strains were in the implicated cantaloupe, and in the packing shed.

- Without PulseNet, we would not know that illnesses in different states were part of the same outbreak, and we might not even know that multiple states were affected.

- Without PulseNet, many multistate outbreaks would not be detected or controlled at all.

- For example, the large outbreak of Salmonella infections in 2009 that was linked to peanut butter (714 cases and 6 deaths in 46 states, more than 3,900 different tainted products recalled), would not have been detected at all, and might have continued for months or years.

PulseNet: A Good Value

PulseNet triggered outbreak investigations have resulted in the recall of well over one half billion pounds of contaminated food. More importantly, these investigations have highlighted unrecognized problems in food production and distribution industries, such as the beef, produce, tree nut, peanut, egg, and spice industries, ultimately resulting in major change to industrial processes and improved food safety. A soon-to-be-released study will show a very high ratio cost-benefit ratio for PulseNet and associated outbreak investigation programs.

Currently, PulseNet is developing MLVA (multiple locus variable number tandem repeat analysis) as an alternate way to examine foodborne illness pathogens. MLVA is a DNA “fingerprinting” method used to identify distinct lineages of microbes and is widely used to identify disease-causing foodborne bacteria. Comparing the MLVA profile of a microbe infecting patients to that in the food sample helps investigators locate the source of an outbreak with confidence; then they can take steps to remove it from the market.

Preparing for the Future

“At CDC, we work 24/7 to protect people from threats and to do that we need good information. Some of that information comes from an old fashioned test of growing up a bacteria in a laboratory, subjecting it to DNA fingerprinting to figure out exactly which strain it is and whether it’s related to another strain, and then doing that shoe-leather epidemiology to figure out if two people have the same organism-did they eat the same food, what was that food, and getting that food off the shelves,” says Thomas Frieden, Director of CDC.2

More and more diagnostic tests that do not use culture are being developed and marketed for clinical use, including use by clinical laboratories in diagnosing foodborne infections. Because of their rapid turnaround times and less labor-intensive methodology, these tests may soon replace culture-based tests, necessitating fundamental changes and challenges in public health efforts to track and control infectious diseases.3

Since isolates are necessary for public health surveillance programs like PulseNet, new “culture-independent” molecular strain typing and characterization methods need to be developed that are compatible with, or complement, tests developed in the private sector so that the needs of both patients and public health are met. Partnering with the clinical diagnostic community and medical device industry is critical for finding solutions that will enable public health systems to continue addressing foodborne outbreaks while embracing new technology.3

More Information

- CDC PulseNet Site

- Enteric Diseases Laboratory Branch

- PulseNet at Work: Detecting Hazardous Hazelnuts

- DNA “Fingerprinting” and Investigation of Organisms to Detect Outbreaks

- Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL), Food Safety

- Fecal Matters: It All Starts with a Stool Sample

- Food Safety Success Stories

- APHL Lab Matters, Spring 2011

References

- Griffin PM, Bell BP, Cieslak PR, Tuttle J, Barrett TJ, Doyle MP, Mcnamara AM, Shefer AM, Wells JG. Large Outbreak of Escherichia-Coli O157-H7 Infections in the Western United-States – the Big Picture. Int Congr Ser. 1994;1072:7-12. [PDF – 644KB]

- CBS This Morning. Food Poisoning Fix? 2013 [cited January 8, 2013]; Available from: http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=50136967n

- Major Foodborne Illness Outbreaks of 2012. 2013 [cited February 11, 2013]; Available from: http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/foodborne-outbreaks

- Page last reviewed: February 27, 2013

- Page last updated: February 27, 2013

- Content source:

- National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases

- Page maintained by: Office of the Associate Director for Communication, Digital Media Branch, Division of Public Affairs

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir