Introduction to Program Evaluation for Public Health Programs: A Self-Study Guide

On this Page

- Matching Terms from Planning and Evaluation

- Illustrating Program Descriptions

- Relating Activities and Outcomes: Developing and Using Logic Models

- Exhibit 2.1 - Basic Program Logic Model

- Exhibit 2.2 - Clean Up the Logic Model

- Exhibit 2.3 - Elaborating Your Logic Models “Downstream”

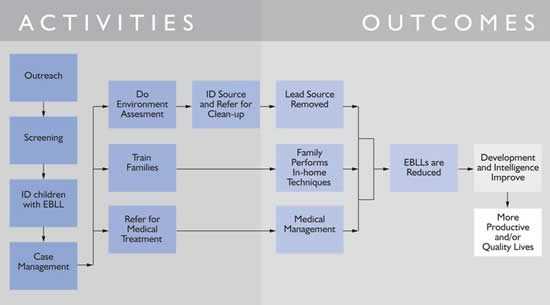

- Exhibit 2.4

- Exhibit 2.4 – Elaborating Intermediate Outcomes In Your Logic Model

- Exhibit 2.5 - Focusing in on Portions of a Program

- Standards for Step 2: Describe the Program

- Checklist for Step 2: Describing the Program

- Worksheet 2A - Raw Material for Your Logic Model

- Worksheet 2B - Sequencing Activities and Outcomes

Step 2: Describe the Program

A comprehensive program description clarifies all the components and intended outcomes of the program, thus helping you focus your evaluation on the most central and important questions. Note that in this step you are describing the program and not the evaluation. In this chapter, you will use a tool called “logic modeling” to depict these program components, but a program description can be developed without using this or any tool.

This step can either follow the stakeholder step or precede it. Either way, the combination of stakeholder engagement and program description produces clarity and consensus long before data are available to measure program effectiveness. This clarity sets the stage for good program evaluation, and, also can be helpful in ensuring that strategic planning and performance measurement, operate from the same frame of reference about the program.

A comprehensive program description includes the following components:

- Need. What is the big public health problem you aim to address with your program?

- Targets. Which groups or organizations need to change or take action to ensure progress on the public health problem?

- Outcomes. How and in what way do these targets need to change? What action specifically do they need to take?

- Activities. What will your program and its staff do to move these target groups to change/take action?

- Outputs. What tangible capacities or products will be produced by your program’s activities?

- Resources/Inputs. What is needed from the larger environment in order for the activities to be mounted successfully?

- Relationship of Activities and Outcomes. Which activities are being implemented to produce progress on which outcomes?

In addition to specifying these components, a complete program description includes discussion of:

- Stage of Development. Is the program just getting started, is it in the implementation stage, or has it been underway for a significant period of time?

- Context. What factors and trends in the larger environment may influence program success or failure?

Matching Terms from Planning and Evaluation

Planning and evaluation are companion processes. Unfortunately, they may use different terms for similar concepts. The resulting confusion undermines integration of planning and evaluation. As noted below, plans proceed from abstract/conceptual goals, then specify tangible objectives needed to reach them, and then the strategies needed to reach the objectives. These strategies may be specified as actions, tactics, or a host of other terms. These terms may crosswalk to the components of our program description. The strategies may provide insights on the program’s activities, the objectives may indicate some or all of the target audiences and short-term or intermediate outcomes, and the goal is likely to inform the long-term outcome desired by the program.

You need not start from scratch in defining the components of your program description. Use the goals and objectives in the program’s mission, vision, or strategic plan to generate a list of outcomes (see text box). The specific objectives outlined in documents like Healthy People 2010 are another starting point for defining some components of the program description for public health efforts (see http://www.health.gov/healthypeople).

Top of PageIllustrating Program Descriptions

Let’s use some of our cases to illustrate the components of a program description.

Need for the Program

The need is the public health or other problem addressed by the program. You might define the need, in terms of its consequences for the state or community, the size of the problem overall, the size of the problem in various segments of the population, and/or significant changes or trends in incidence or prevalence.

For example, the problem addressed by the affordable housing program is compromised life outcomes for low-income families due to lack of stability and quality of housing environments. The need for the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention (CLPP) program is halting the developmental slide that occurs in children with elevated blood-lead levels (EBLL).

Target Groups

Target groups are the various audiences the program needs to spur to act in order to make progress on the public health problem. For the affordable housing program, eligible families, volunteers, and funders/sponsors need to take action. For the CLPP program, reducing EBLL requires some action by families, health care providers, and housing officials, among others.

Outcomes

Outcomes [15] are the changes in someone or something (other than the program and its staff) that you hope will result from your program’s activities. For programs dealing with large and complex public health problems, the ultimate outcome is often an ambitious and long-term one, such as eliminating the problem or condition altogether or improving the quality of life of people already affected. Hence, a strong program description provides details not only on the intended long-term outcomes but on the short-term and intermediate outcomes that precede it.

Outcomes [15] are the changes in someone or something (other than the program and its staff) that you hope will result from your program’s activities. For programs dealing with large and complex public health problems, the ultimate outcome is often an ambitious and long-term one, such as eliminating the problem or condition altogether or improving the quality of life of people already affected. Hence, a strong program description provides details not only on the intended long-term outcomes but on the short-term and intermediate outcomes that precede it.

The text box “A Potential Hierarchy of Effects” outlines a potential sequence for a program’s outcomes (effects). Starting at the base of the hierarchy: Program activities aim to obtain participation among targeted communities. Participants’ reactionsto program activities affect their learning—their knowledge, opinions, skills, and aspirations. Through this learning process, people and organizations take actions that result in a change in social, behavioral, and/or environmental conditions that direct the long-term health outcomes of the community.

Keep in mind that the higher order outcomes are usually the “real” reasons the program was created, even though the costs and difficulty of collecting evidence increase as you move up the hierarchy. Evaluations are strengthened by showing evidence at several levels of hierarchy; information from the lower levels helps to explain results at the upper levels, which are longer term.

The sequence of outcomes for the affordable housing program is relatively simple: Families, sponsors, and volunteers must be engaged and work together for several weeks to complete the house, then the sponsor must sell the house to the family, and then the family must maintain the house payments.

For the CLPP program, there are streams of outcomes for each of the target groups: Providers must be willing to test, treat, and refer EBLL children. Housing officials must be willing to clean up houses that have lead paint, and families must be willing to get children and houses screened, adopt modest changes in housekeeping behavior, and adhere to any treatment schedule to reduce EBLL in children. Together, these ensure higher order outcomes related to reducing EBLL and arresting the developmental slide.

Activities

These are the actions mounted by the program and its staff to achieve the desired outcomes in the target groups. Activities will vary with the program. Typical program activities may include, among others, outreach, training, funding, service delivery, collaborations and partnerships, and health communication. For example, the affordable housing program must recruit, engage, and train the families, sponsors, and volunteers, and oversee construction and handle the mechanics of home sale. The CLPP program does outreach and screening of children, and, for children with EBLL, does case management, referral to medical care, assessment of the home, and referral of lead-contaminated homes for cleanup.

Outputs

Outputs are the direct products of activities, usually some sort of tangible deliverable. Outputs can be viewed as activities redefined in tangible or countable terms. For example, the affordable housing program’s activities of engaging volunteers, recruiting sponsors, and selecting families have the corresponding outputs: number of volunteers engaged, number of sponsors recruited and committed, and number and types of families selected. The CLPP activities of screening, assessing houses, and referring children and houses would each have a corresponding output: the number of children screened and referred, and the number of houses assessed and referred. [16]

Resources/Inputs

These are the people, money, and information needed—usually from outside the program—to mount program activities effectively. It is important to include inputs in the program description because accountability for resources to funders and stakeholders is often a focus of evaluation. Just as important, the list of inputs is a reminder of the type and level of resources on which the program is dependent. If intended outcomes are not being achieved, look to the resources/inputs list for one reason why program activities could not be implemented as intended.

In the affordable housing program, for example, supervisory staff, community relationships, land, and warehouse are all necessary inputs to activities. For the CLPP program, funds, legal authority to screen children and houses, trained staff, and relationships with organizations responsible for medical treatment and clean-up of homes—are necessary inputs to mount a successful program.

Stages of Development

Programs can be roughly classed into three stages of development: planning, implementation, and maintenance/outcomes achievement. The stage of development plays a central role in setting a realistic evaluation focus in the next step. A program in the planning stage will focus its evaluation very differently than a program that has been in existence for several years.

Both the affordable housing and CLPP programs have been in existence for several years and can be classed in the maintenance/outcomes achievement stage. Therefore, an evaluation of these programs would probably focus on the degree to which outcomes have been achieved and the factors facilitating or hindering the achievement of outcomes.

Context

The context is the larger environment in which the program exists. Because external factors can present both opportunities and roadblocks, be aware of and understand them. Program context includes politics, funding, interagency support, competing organizations, competing interests, social and economic conditions, and history (of the program, agency, and past collaborations).

For the affordable housing program, some contextual issues are the widespread beliefs in the power of home ownership and in community-wide person-to-person contact as the best ways to transform lives. At the same time, gentrification in low-income neighborhood drives real estate prices up, which can make some areas unaffordable for the program. Some communities, while approving affordable housing in principle, may resist construction of these homes in their neighborhood.

For the CLPP program, contextual issues include increasing demands on the time and attention of primary health care providers, the concentration of EBLL children in low-income and minority neighborhoods, and increasing demands on housing authorities to ameliorate environmental risks.

A realistic and responsive evaluation will be sensitive to a broad range of potential influences on the program. An understanding of the context lets users interpret findings accurately and assess the findings’ generalizability. For example, the affordable housing program might be successful in a small town, but may not work in an inner-city neighborhood without some adaptation.

Top of PageRelating Activities and Outcomes: Developing and Using Logic Models

Other Names for a Logic Model

- Theory of change

- Model of change

- Theoretical underpinning

- Causal chain

- Weight-of-evidence model

- Roadmap

- Conceptual map

- Blueprint

- Rationale

- Program theory

- Program hypothesis

Once the components of the program description have been identified, a visual depiction may help to summarize the relationship among components. This clarity can help with both strategic planning and program evaluation. While there are other ways to depict these relationships, logic models are a common tool evaluators use, and the tool described most completely in the CDC Framework.

Logic models are graphic depictions of the relationship between a program’s activities and its intended outcomes. Two words in this definition bear emphasizing:

- Relationship: Logic models convey not only the activities that make up the program and the inter-relationship of those activities, but the link between those components and outcomes.

- Intended: Logic models depict intended outcomes of a program’s activities. As the starting point for evaluation and planning, the model serves as an “outcomes roadmap” that shows the underlying logic behind the program, i.e., why it should work. That is, of all activities that could have been undertaken to address this problem, these activities are chosen because, if implemented as intended, they should lead to the outcomes depicted. Over time, evaluation, research, and day-to-day experience will deepen the understanding of what does and does not work, and the model will change accordingly.

Logic Model Components

Logic models may depict all or only some of the following components of your program description, depending on their intended use:

- Inputs: Resources that go into the program and on which it is dependent to mount its activities.

- Activities: Actual events or actions done by the program and its staff.

- Outputs: Direct products of program activities, often measured in countable terms (e.g., the number of sessions held).

- Outcomes: The changes that result from the program’s activities and outputs, often in a sequence expressed as short-term, intermediate and long-term outcomes.

The logic model requires no new thinking about the program; rather, it converts the raw material generated in the program description into a picture of the program. The remainder of this chapter provides the steps in constructing and elaborating simple logic models. The next chapter, Focus the Evaluation Design, shows how to use the model to identify and address issues of evaluation focus and design.

Constructing Simple Logic Models

A useful logic model can be constructed in a few simple steps, as shown here using the CLPP program for illustration.

Develop a list of activities and intended outcomes

While logic models can include all of the components in the text box, we will emphasize using logic models to gain clarity on the relationship between the program’s activities and its outcomes. To stimulate the creation of a comprehensive list of activities and outcomes, any of the following methods will work.

- Review any information available on the program—whether from mission/vision statements, strategic plans, or key informants— and extract items that meet the definition of activity (something the program and its staff does) and of outcome (thechange you hope will result from the activities), or

- Work backward from outcomes. This is called “reverse logic” logic modeling and may prove helpful when a program is given responsibility for a new or large problem or is just getting started. There may be clarity about the “big change” (most distal outcome) the program is to produce, but little else. Working backward from the distal outcome by asking “how to” will help identify the factors, variables, and actors that will be involved in producing change, or

- Work forward from activities. This is called “forward logic” logic modeling and is helpful when there is clarity about activities but not about why they are part of the program. Moving forward from activities to intended outcomes by asking, “So then what happens?” helps elaborate downstream outcomes of the activities.

Logic models may depict all or only some of the elements of program description (see text box, p.24), depending on the use to which the model is being put. For example, Exhibit 2.1 is a simple, generic logic model. If relevant , the model could include references to components such as “context” or “stage of development.” The examples below focus mainly on connecting a program’s activities to its outcomes. Adding “inputs” and explicit “outputs” to these examples would be a simple matter if needed.

Top of PageExhibit 2.1 - Basic Program Logic Model

Note that Worksheet 2A at the end of this chapter provides a simple format for doing this categorization of activities and outcomes, no matter what method is used. Here, for the CLPP, we completed the worksheet using the first method.

| CLPP Program: Listing Activities and Outcomes | |

|---|---|

ACTIVITIES

| OUTCOMES

|

Subdivide the lists to show the logical sequencing among activities and outcomes. Logic models provide clarity on the order in which activities and outcomes are expected to occur. To help provide that clarity, it is useful to take the single column of activities (or outcomes) developed in the last step, and then distribute them across two or more columns to show the logical sequencing. The logical sequencing may be the same as the time sequence, but not always. Rather, the logical sequence says, “Before this activity (or outcome) can occur, this other one has to be in place.”

For example, if the list of activities includes a needs assessment, distribution of a survey, and development of a survey, a needs assessment should be conducted, then the survey should be developed and distributed.. Likewise, among the outcomes, change in knowledge and attitudes would generally precede change in behavior.

Worksheet 2B provides a simple format for expanding the initial two-column table. For the CLPP, we expanded the initial two-column table to four columns. No activities or outcomes have been added, but the original lists have been spread over several columns to reflect the logical sequencing. For the activities, we suggest that outreach, screening, and identification of EBLL children need to occur in order to case manage, assess the houses, and refer the children and their houses to follow-up. On the outcomes sides, we suggest that outcomes such as receipt of medical treatment, clean-up of the house, and adoption of housekeeping changes must precede reduction in EBLL and elimination of the resultant slide in development and quality of life.

| CLPP Program: Sequencing Activities and Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Activities | Later Activities | Early Outcomes | Later Outcomes |

|

|

|

|

Add any inputs and outputs. At this point, you may decide that the four-column logic model provides all the clarity that is needed. If not, the next step is to add columns for inputs and for outputs. The inputs are inserted to the left of the activities while the outputs—as products of the activities—are inserted to the right of the activities but before the outcomes.

For the CLPP, we can easily define and insert both inputs and outputs of our efforts. Note that the outputs are the products of our activities. Do not confuse them with outcomes. No one has changed yet. While we have identified a pool of leaded houses and referred a pool of EBLL children, the houses have not been cleaned up, nor have the children been treated yet.

| CLPP Program: Logic Model with Inputs and Outputs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inputs | Early Activities | Later Activities | Outputs | Early Outcomes | Later Outcomes |

Funds Trained staff for screening and clean-up Relationships with organizations Legal authority | Outreach Screening Identification of EBLL children | Case management Referral to medical treatment Environmental assessment Environmental referral Family training | Pool (#) of eligible children Pool (#) of screened children Referrals (#) to medical treatment Pool (#) of “leaded” homes Referrals (#) for clean-up | Lead source identified Lead source gets eliminated Families adopt in-home techniques EBLL children get medical treatment | EBLL reduced Development “slide” stopped Q of L improved |

Draw arrows to depict intended causal relationships. The multi-column table of inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes that has been developed so far contains enough detail to convey the components of a program in a global way. However, when the model is used to set the stage for planning and evaluation discussions, drawing arrows that show the causal relationships among activities and outcomes can be helpful. These arrows may depict a variety of relationships: from one activity to another, when the first activity exists mainly to feed later activities; from an activity to an outcome, where the activity is intended to produce a change in someone or something other than the program; from an early outcome to a later one, when the early outcome is necessary to achieve the more distal outcome.

Examine the CLPP Logic Model (Exhibit 2.2) with causal arrows included. Note that no activities/outputs or outcomes have been added. Instead, arrows were added to show the relationships among activities and outcomes. Note also that streams of activities exist concurrently to produce cleaned-up houses, medically “cured” children, and trained and active households/families. It is the combination of these three streams that produces reductions in EBLL, which is the platform for stopping the developmental slide and improving the quality of life.

Top of PageExhibit 2.2 - Clean Up the Logic Model

Early versions are likely to be sloppy, and a nice, clean one that is intelligible to others often takes several tries.

Elaborate the Simple Model

Logic models are a picture depicting your “program theory”—why should your program work? The simple logic models developed in these few steps may work fine for that purpose, but programs may benefit from elaborating their simple logic models in some of the following ways:

- Elaborating distal outcomes: Sometimes the simple model will end with short-term outcomes or even outputs. While this may reflect a program’s mission, usually the program has been created to contribute to some larger purpose, and depicting this in the model leads to more productive strategic planning discussions later. Ask, “So then what happens?” of the last outcome depicted in the simple model, then continuing to ask that of all subsequent outcomes until more distal ones are included.

In Exhibit 2.3, the very simple logic model that might result from a review of the narrative about the home ownership program is elaborated by asking, “So then what happens?” Note that the original five-box model remains as the core of the elaborated model, but the intended outcomes now include a stream of more distal outcomes for both the new home-owning families and for the communities in which houses are built. The elaborated model can motivate the organization to think more ambitiously about intended outcomes and whether the right activities are in place to produce them.

Exhibit 2.3 - Elaborating Your Logic Models “Downstream”

Elaborating intermediate outcomes: Sometimes the initial model presents the program’s activities and its most distal outcome in detail, but with scant information on how the activities are to produce the outcomes.In this case, the goal of elaboration is to better depict the program logic that links activities to the distal outcomes. Providing such a step-by-step roadmap to a distal destination can help identify gaps in program logic that might not otherwise be apparent; persuade skeptics that progress is being made in the right direction, even if the destination has not yet been reached; aid program managers in identifying what needs to be emphasized right now and/or what can be done to accelerate progress.

For example, the mission of many CDC programs can be displayed as a simple logic model that shows key clusters of program activities and the key intended changes in a health outcome(s) (Exhibit 2.4). Elaboration leads to the more detailed depiction of how the same activities produce the major distal outcome, i.e., the milestones along the way.

Top of PageExhibit 2.4

Exhibit 2.4 – Elaborating Intermediate Outcomes In Your Logic Model

Setting the Appropriate Level of Detail

Logic models can be broad or specific. The level of detail depends on the use to which the model is being put and the main audience for the model. A global model works best for stakeholders such as funders and authorizers, but program staff may need a more detailed model that reflects day-to-day activities and causal relationships.

When programs need both global and specific logic models, it is helpful to develop a global model first. The detailed models can be seen as more specific “magnification” of parts of the program. As in geographic mapping programs such as Mapquest, the user can “zoom in” or “zoom out” on an underlying map. The family of related models ensures that all players are operating from a common frame of reference. Even when some staff members are dealing with a discrete part of the program, they are cognizant of where their part fits into the larger picture.

The provider immunization program is a good example of “zooming in” on portions of a more global model. The first logic model (Exhibit 2.5) is a global one depicting all the activities and outcomes, but highlighting the sequence from training activities to intended outcomes of training. The second logic model magnifies this stream only, indicating some more detail related to implementation of training activities.

Top of PageExhibit 2.5 - Focusing in on Portions of a Program

Applying Standards

As in the previous step, you can assure that the evaluation is a quality one by testing your approach against some or all of the four evaluation standards. The two standards that apply most directly to Step 2: Describe the Program are accuracy and propriety. The questions presented in the following table can help you produce the best program description.

Standards for Step 2: Describe the Program

| Standard | Questions |

|---|---|

| Utility |

|

| Feasibility |

|

| Propriety |

|

| Accuracy |

|

Checklist for Step 2: Describing the Program

- Compile a comprehensive program description including need, targets, outcomes, activities, and resources.

- Identify the stage of development and context of the program.

- Convert inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes into a simple global logic model.

- Elaborate the model as needed.

- Develop more detailed models from the global model as needed.

Worksheet 2A - Raw Material for Your Logic Model

| ACTIVITIES | OUTCOMES |

|---|---|

| What will the program and its staff actually do? | What changes do we hope will result in someone or something other than the program and its staff? |

Worksheet 2B - Sequencing Activities and Outcomes

| ACTIVITIES | OUTCOMES | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Later | Early | Later |

Contact Evaluation Program

E-mail: cdceval@cdc.gov

- Page last reviewed: May 11, 2012

- Page last updated: May 11, 2012

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir