Strongyloidiasis

[Strongyloides stercoralis]

Causal Agents

The nematode (roundworm) Strongyloides stercoralis. Other Strongyloides include S. fülleborni, which infects chimpanzees and baboons and may produce limited infections in humans.

Life Cycle

The Strongyloides life cycle is more complex than that of most nematodes with its alternation between free-living and parasitic cycles, and its potential for autoinfection and multiplication within the host. Two types of cycles exist: Free-living cycle: The rhabditiform larvae passed in the stool  (see "Parasitic cycle" below) can either become infective filariform larvae (direct development)

(see "Parasitic cycle" below) can either become infective filariform larvae (direct development) , or free-living adult males and females

, or free-living adult males and females  that mate and produce eggs

that mate and produce eggs  from which rhabditiform larvae hatch

from which rhabditiform larvae hatch  and eventually become infective filariform larvae

and eventually become infective filariform larvae  . The filariform larvae penetrate the human host skin to initiate the parasitic cycle (see below)

. The filariform larvae penetrate the human host skin to initiate the parasitic cycle (see below)  . Parasitic cycle: Filariform larvae in contaminated soil penetrate the human skin

. Parasitic cycle: Filariform larvae in contaminated soil penetrate the human skin  , and by various, often random routes, migrate to the small intestine

, and by various, often random routes, migrate to the small intestine  . Historically it was believed that the L3 larvae migrate via the bloodstream to the lungs, where they are eventually coughed up and swallowed. However, there is also evidence that L3 larvae can migrate directly to the intestine via connective tissues. In the small intestine they molt twice and become adult female worms

. Historically it was believed that the L3 larvae migrate via the bloodstream to the lungs, where they are eventually coughed up and swallowed. However, there is also evidence that L3 larvae can migrate directly to the intestine via connective tissues. In the small intestine they molt twice and become adult female worms  . The females live threaded in the epithelium of the small intestine and by parthenogenesis produce eggs

. The females live threaded in the epithelium of the small intestine and by parthenogenesis produce eggs , which yield rhabditiform larvae. The rhabditiform larvae can either be passed in the stool

, which yield rhabditiform larvae. The rhabditiform larvae can either be passed in the stool  (see "Free-living cycle" above), or can cause autoinfection

(see "Free-living cycle" above), or can cause autoinfection  . In autoinfection, the rhabditiform larvae become infective filariform larvae, which can penetrate either the intestinal mucosa (internal autoinfection) or the skin of the perianal area (external autoinfection); in either case, the filariform larvae may disseminate throughout the body. To date, occurrence of autoinfection in humans with helminthic infections is recognized only in Strongyloides stercoralis and Capillaria philippinensis infections. In the case of Strongyloides, autoinfection may explain the possibility of persistent infections for many years in persons who have not been in an endemic area and of hyperinfections in immunodepressed individuals.

. In autoinfection, the rhabditiform larvae become infective filariform larvae, which can penetrate either the intestinal mucosa (internal autoinfection) or the skin of the perianal area (external autoinfection); in either case, the filariform larvae may disseminate throughout the body. To date, occurrence of autoinfection in humans with helminthic infections is recognized only in Strongyloides stercoralis and Capillaria philippinensis infections. In the case of Strongyloides, autoinfection may explain the possibility of persistent infections for many years in persons who have not been in an endemic area and of hyperinfections in immunodepressed individuals.

Geographic Distribution

Tropical and subtropical areas, but cases also occur in temperate areas (including the South of the United States). More frequently found in rural areas, institutional settings, and lower socioeconomic groups.

Clinical Presentation

Frequently asymptomatic. Gastrointestinal symptoms include abdominal pain and diarrhea. Pulmonary symptoms (including Loeffler’s syndrome) can occur during pulmonary migration of the filariform larvae. Dermatologic manifestations include urticarial rashes in the buttocks and waist areas. Disseminated strongyloidiasis occurs in immunosuppressed patients, can present with abdominal pain, distension, shock, pulmonary and neurologic complications and septicemia, and is potentially fatal. Blood eosinophilia is generally present during the acute and chronic stages, but may be absent with dissemination.

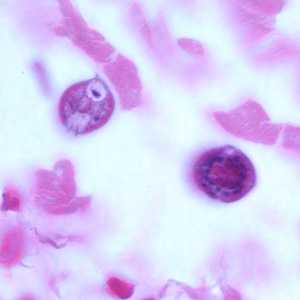

Strongyloides stercoralis first-stage rhabditiform (L1) larvae.

Figure A: Rhabditiform larva of S. stercoralis in unstained wet mounts of stool. Notice the short buccal canal and the genital primordium (red arrows).

Figure B: Rhabditiform larva of S. stercoralis in unstained wet mounts of stool. Notice the short buccal canal and the genital primordium (red arrows).

Figure C: Close-up of the anterior end of a rhabditiform larva of S. stercoralis, showing the short buccal canal (red arrow) and the rhabditoid esophagus (blue arrow). Image taken at 1000x oil magnification.

Figure D: Rhabditiform larva of S. stercoralis in an unstained wet mount of stool. Notice the short buccal canal and the genital primordium (red arrow).

Figure E: Rhabditiform larva of S. stercoralis in an unstained wet mount of stool. Notice the rhabditoid esophagus (blue arrow) and prominent genital primordium (red arrow).

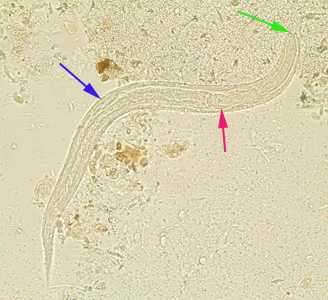

Figure F: Rhabditiform larva of S. stercoralis in an unstained wet mount of stool. Notice the prominent genital primordium (blue arrow), rhabditoid esophagus (red arrow) and short buccal canal (green arrow).

Strongyloides stercoralis third-stage filariform (L3) larvae.

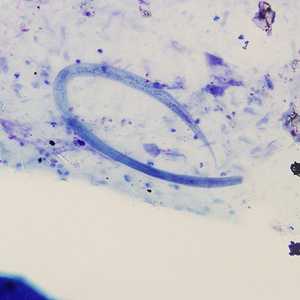

Figure A: Filariform (L3) larva of S. stercoralis in an unstained wet mount.

Figure B: Filariform (L3) larva of S. stercoralis in a sputum specimen, stained with Giemsa. Image taken at 200x magnification.

Figure C: Higher magnification (1000x oil) of the worm in Figure B. Notice the notched tail.

Strongyloides stercoralis free-living adults.

Figure A: Free-living adult male S. stercoralis. Notice the presence of the spicule (red arrow).

Figure B: Free living adult male S. stercoralis, showing a spicule (red arrow). A smaller, rhabditiform larva lies adjacent to the adult male.

Figure C: Adult free-living female S. stercoralis alongside a smaller rhabditiform larva. Notice the developing eggs in the adult female.

Figure D: Adult free-living female S. stercoralis. Notice the row of eggs within the female’s body.

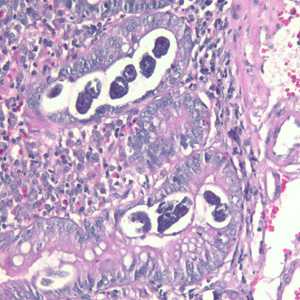

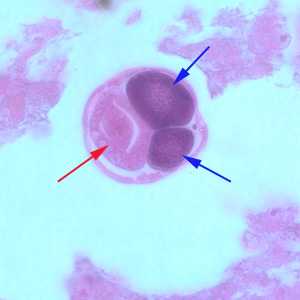

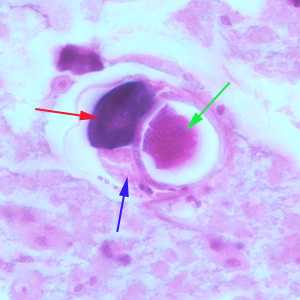

Strongyloides stercoralis in tissue.

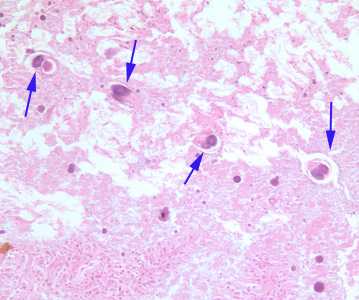

Figure A: Cross-sections of female S. stercoralis (blue arrows) in small intestine tissue, stained with H&E. Image taken at 200x magnification.

Figure B: Sections of S. stercoralis from a duodenal biopsy specimen, stained with H&E. Although strongyloidiasis could not be confirmed based on microscopy alone, this case was confirmed using molecular methods (PCR). Image taken at 200x magnification.

Figure C: Higher magnification (1000x oil) of a female of S. stercoralis from the same specimen as Figure A. Notice the intestine (red arrow) and ovaries (blue arrows).

Figure D: Higher magnification (1000x oil) of a gravid female of S. stercoralis from the same specimen as Figure A. Notice the intestine (blue arrow), ovary (red arrow) and an egg within the uterus (green arrow).

Figure E: Cross-sections of larvae of S. stercoralis in a intestinal biopsy specimen, stained with H&E. Image taken at 1000x oil magnification. The patient was infected with Strongyloides following transplant of an infected kidney.

Figure F: Longitudinal-section of a larva of S. stercoralis from the same specimen as Figure E. Image taken at 400x magnification.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Diagnosis rests on the microscopic identification of larvae (rhabditiform and occasionally filariform) in the stool or duodenal fluid. Examination of serial samples may be necessary, and not always sufficient, because stool examination is relatively insensitive.

The stool can be examined in wet mounts:

- directly

- after concentration (formalin-ethyl acetate)

- after recovery of the larvae by the Baermann funnel technique

- after culture by the Harada-Mori filter paper technique

- after culture in agar plates

The duodenal fluid can be examined using techniques such as the Enterotest string or duodenal aspiration. Larvae may be detected in sputum from patients with disseminated strongyloidiasis.

Antibody Detection

Immunodiagnostic tests for strongyloidiasis are indicated when the infection is suspected and the organism cannot be demonstrated by duodenal aspiration, string tests, or by repeated examinations of stool. Antibody detection tests should use antigens derived from Strongyloides stercoralis filariform larvae for the highest sensitivity and specificity. Although indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) and indirect hemagglutination (IHA) tests have been used, enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is currently recommended because of its greater sensitivity (90%). Immunocompromised persons with disseminated strongyloidiasis usually have detectable IgG antibodies despite their immunodepression. Cross-reactions in patients with filariasis and some other nematode infections may occur. Antibody test results cannot be used to differentiate between past and current infection. A positive test warrants continuing efforts to establish a parasitological diagnosis followed by antihelminthic treatment. Serologic monitoring may be useful in the follow-up of immunocompetent treated patients: antibody levels decrease markedly within 6 months after successful chemotherapy.

References:

- Loutfy MR, Wilson M, Keystone JS, Kain KC. 2002. Serology and eosinophil count in the diagnosis and management of strongyloidiasis in a non-endemic area. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 66:749-52.

- Genta RM. Predictive value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the serodiagnosis of strongyloidiasis. Am J Clin Pathol 1988;89:391-394.

Treatment Information

Acute and chronic strongyloidiasis

First line therapy

Ivermectin, in a single dose, 200 µg/kg orally for 1-2 days

Relative contraindications:

- confirmed or suspected concomitant Loa loa infection

- persons weighing less than 15kg

- pregnant or lactating women

Ivermectin

Oral ivermectin is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir