Onchocerciasis

[Onchocerca volvulus]

Causal Agent

Onchocerca volvulus causes onchocerciasis (river blindness).

Life Cycle

During a blood meal, an infected blackfly (genus Simulium) introduces third-stage filarial larvae onto the skin of the human host, where they penetrate into the bite wound  . In subcutaneous tissues the larvae

. In subcutaneous tissues the larvae  develop into adult filariae, which commonly reside in nodules in subcutaneous connective tissues

develop into adult filariae, which commonly reside in nodules in subcutaneous connective tissues  . Adults can live in the nodules for approximately 15 years. Some nodules may contain numerous male and female worms. Females measure 33 to 50 cm in length and 270 to 400 µm in diameter, while males measure 19 to 42 mm by 130 to 210 µm. In the subcutaneous nodules, the female worms are capable of producing microfilariae for approximately 9 years. The microfilariae, measuring 220 to 360 µm by 5 to 9 µm and unsheathed, have a life span that may reach 2 years. They are occasionally found in peripheral blood, urine, and sputum but are typically found in the skin and in the lymphatics of connective tissues

. Adults can live in the nodules for approximately 15 years. Some nodules may contain numerous male and female worms. Females measure 33 to 50 cm in length and 270 to 400 µm in diameter, while males measure 19 to 42 mm by 130 to 210 µm. In the subcutaneous nodules, the female worms are capable of producing microfilariae for approximately 9 years. The microfilariae, measuring 220 to 360 µm by 5 to 9 µm and unsheathed, have a life span that may reach 2 years. They are occasionally found in peripheral blood, urine, and sputum but are typically found in the skin and in the lymphatics of connective tissues  . A blackfly ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal

. A blackfly ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal  . After ingestion, the microfilariae migrate from the blackfly's midgut through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles

. After ingestion, the microfilariae migrate from the blackfly's midgut through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles  . There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae

. There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae  and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae

and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae  . The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the blackfly's proboscis

. The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the blackfly's proboscis  and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal

and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal  .

.

Geographic Distribution

The agent of river blindness, Onchocerca volvulus, occurs mainly in Africa, with additional foci in Latin America and the Middle East.

Clinical Presentation

Onchocerciasis can cause pruritus, dermatitis, onchocercomata (subcutaneous nodules), and lymphadenopathies. The most serious manifestation consists of ocular lesions that can progress to blindness.

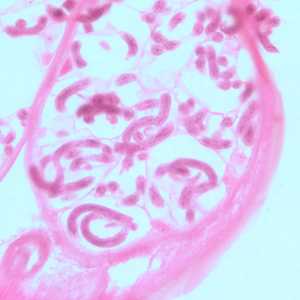

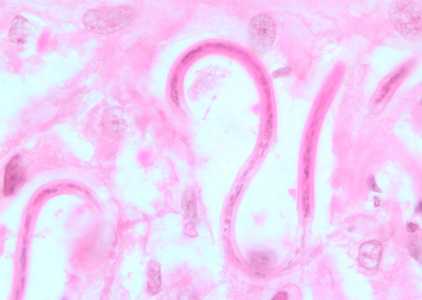

Microfilariae of Onchocerca volvulus in tissue.

Figure A: Microfilariae of O. volvulus from a skin nodule of a patient from Zambia, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Image taken at 1000x oil magnification.

Figure B: Microfilariae of O. volvulus within the uterus of an adult female. The specimen was taken from the same patient as in Figure A. Image taken at 500x magnification, oil.

Figure C: Microfilariae of O. volvulus from a skin nodule of a patient from Zambia, stained with H&E. Image taken at 1000x oil magnification.

Figure D: Coiled microfilaria of O. volvulus, in a skin nodule from a patient from Zambia, stained with H&E. Image taken at 1000x oil magnification.

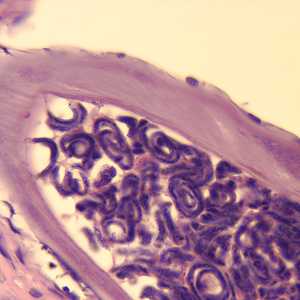

Figure E: Cross-section of an adult female O. volvulus, stained with H&E. Note the presence of many microfilariae within the uterus.

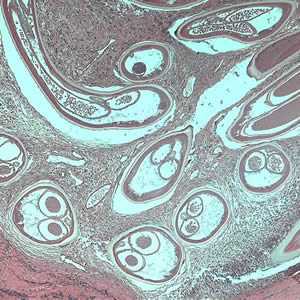

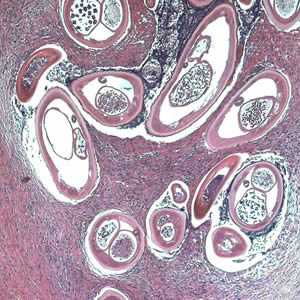

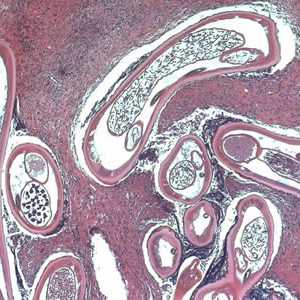

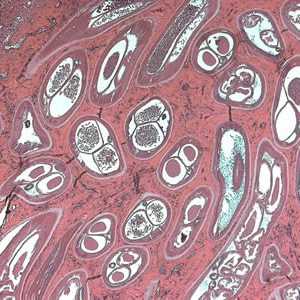

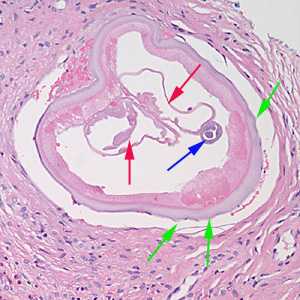

Adults of O. volvulus in tissue.

Figure A: Adult of O. volvulus in a subcutaneous nodule, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure B: Adult of O. volvulus in a subcutaneous nodule, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure C: Adult of O. volvulus in a subcutaneous nodule, stained with H&E.

Figure D: Adult of O. volvulus in a subcutaneous nodule, stained with H&E.

Figure E: Cross-section of an adult female Onchocerca sp. from the biopsy of a scalp nodule from a patient from Liberia. Note the presence of the intestine (blue arrow), uterine tubes (red arrows) and some cuticular nodules (green arrows). Also notice the weak musculature under the thick cuticle. Image courtesy of Drs. Philip LeBoit and Paul Borbeau.

Diagnostic Findings

Microscopy

Onchocerciasis is usually diagnosed by the finding of microfilariae in skin snips or adults in biopsy specimens of skin nodules. Microfilariae of Onchocerca do not exhibit any form of periodicity and skin snips may be collected at any time.

Skin snips should be thin enough to include the outer part of the dermal palpillae but not so thick as to produce bleeding. Skin snips should be placed immediately in normal saline or distilled water, just enough to cover the specimen. Microfilariae tend to emerge more rapidly in saline, however in either medium the microfilariae typically emerge in 30-60 min and can be seen in wet mount preparations. For a definitive diagnosis, allow the wet mount to dry, fix in methanol, and stain with Giemsa or hematoxylin-and-eosin.

Treatment Information

General principles of treatment (see table below for dosing and precautions)

The treatment of choice for onchocerciasis is ivermectin, which has been shown to reduce the occurrence of blindness and to reduce the occurrence and severity of skin symptoms. Ivermectin kills the microfilariae (larvae), but not the macrofilariae (adult worms). There is no evidence that prolonged daily treatment provides any benefit over annual treatment, as one dose results in a significant decrease in microfilarial load that lasts a year or more. Treatment with higher than recommended doses has an increased incidence of side effects and may even be harmful. Although ivermectin does not kill the macrofilariae, it does sterilize the females. There is evidence that treating people with ivermectin more frequently than once a year facilitates more rapid sterilization of the female and that treating a person who no longer lives in an endemic area more frequently, such as every 3 to 6 months, could result in a shorter duration of symptoms. Treatment for a patient who will not be returning to live in an endemic area should be given every 6 months (and dosing as frequent as every 3 months could be considered) for as long as there is evidence of continued infection. Evidence of continued infection would include skin symptoms such as pruritus, microfilariae in skin biopsies, and microfilariae on eye exam. Finding adult worms in nodules would not necessarily constitute evidence of the need for continued treatment, as the macrofilariae do not cause symptoms and ivermectin does not kill the macrofilariae. Treatment with ivermectin can cause mild symptoms associated with death of the microfilariae, such as increase itching, but there is no worsening of eye symptoms. Severe adverse reactions to ivermectin in the absence of Loa loa co-infection are rare.

An evolving treatment is doxycycline, which has been shown in studies to kill Wolbachia, an endosymbiotic rickettsia-like bacterium that appears to be required for the survival of the O. volvulus macrofilariae and for embryogenesis. Treatment with a 6-week course of doxycycline has been shown to kill more than 60% of the adult female worms and to sterilize 80 to 90% of the females 20 months after treatment. Doxycycline does not kill the microfilariae, so treatment with ivermectin would be needed to result in a more rapid decrease of symptoms. Most protocols that have examined the effectiveness of doxycycline had given treatment with ivermectin 4 to 6 months after treatment with doxycycline, so the safety of simultaneous treatment is not known. Treating with ivermectin one week prior to starting doxycycline would be reasonable. As doxycycline does not result in the rapid death of the parasites and as most of the mild side effects of ivermectin treatment are thought to be related to rapid release of Wolbachia antigens, the side effect profile of the medication when used for the treatment of onchocerciasis does not appear to be different than that of its use for other indications. There are limited data to suggest that treatment of onchocerciasis with doxycycline in patients co-infected with Loa loa is safe, but this is limited to one randomized controlled trial where only people with Loa microfilarial loads < 8,000 per mL were treated and one community-based study of doxycycline treatment in co-endemic areas in which Loa microfilarial loads were not determined.

Older treatments for onchocerchiasis, such as suramin and diethylcarbamazine should not be used. Suramin has multiple systemic toxicities that limit its use in the presence of other less toxic and effective therapies. Diethylcarbamazine accelerates the development of onchocercal blindness.

Treatments for Onchocerca volvulus

| Usage/Drug | Adult Dose | Pediatric dose |

|---|---|---|

| To kill microfilariae: ivermectin |

150 mcg/kg orally in one dose every 6 months |

150 mcg/kg orally in one dose every 6 months |

| To kill macrofilariae: doxycycline* |

200 mg orally daily for 6 weeks |

200 mg orally daily for 6 weeks |

Ivermectin

Oral ivermectin is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir