Leishmaniasis

[Leishmania spp.]

Causal Agent

Leishmaniasis is a vector-borne disease that is transmitted by sandflies and caused by obligate intracellular protozoa of the genus Leishmania. Human infection is caused by about 21 of 30 species that infect mammals. These include the L. donovani complex with 3 species (L. donovani, L. infantum, and L. chagasi); the L. mexicana complex with 3 main species (L. mexicana, L. amazonensis, and L. venezuelensis); L. tropica; L. major; L. aethiopica; and the subgenus Viannia with 4 main species (L. (V.) braziliensis, L. (V.) guyanensis, L. (V.) panamensis, and L. (V.) peruviana). The different species are morphologically indistinguishable, but they can be differentiated by isoenzyme analysis, molecular methods, or monoclonal antibodies.

Life Cycle

Leishmaniasis is transmitted by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sandflies. The sandflies inject the infective stage (i.e., promastigotes) from their proboscis during blood meals  . Promastigotes that reach the puncture wound are phagocytized by macrophages

. Promastigotes that reach the puncture wound are phagocytized by macrophages  and other types of mononuclear phagocytic cells. Promastigotes transform in these cells into the tissue stage of the parasite (i.e., amastigotes)

and other types of mononuclear phagocytic cells. Promastigotes transform in these cells into the tissue stage of the parasite (i.e., amastigotes)  , which multiply by simple division and proceed to infect other mononuclear phagocytic cells

, which multiply by simple division and proceed to infect other mononuclear phagocytic cells  . Parasite, host, and other factors affect whether the infection becomes symptomatic and whether cutaneous or visceral leishmaniasis results. Sandflies become infected by ingesting infected cells during blood meals (

. Parasite, host, and other factors affect whether the infection becomes symptomatic and whether cutaneous or visceral leishmaniasis results. Sandflies become infected by ingesting infected cells during blood meals ( ,

,  ). In sandflies, amastigotes transform into promastigotes, develop in the gut

). In sandflies, amastigotes transform into promastigotes, develop in the gut  (in the hindgut for leishmanial organisms in the Viannia subgenus; in the midgut for organisms in the Leishmania subgenus), and migrate to the proboscis

(in the hindgut for leishmanial organisms in the Viannia subgenus; in the midgut for organisms in the Leishmania subgenus), and migrate to the proboscis  .

.

Geographic Distribution

Leishmaniasis is found in parts of about 88 countries. Approximately 350 million people live in these areas. Most of the affected countries are in the tropics and subtropics. The settings in which leishmaniasis is found range from rain forests in Central and South America to deserts in West Asia. More than 90 percent of the world's cases of visceral leishmaniasis are in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil.

Leishmaniasis is found in Mexico, Central America, and South America—from northern Argentina to Texas (not in Uruguay, Chile, or Canada), southern Europe (leishmaniasis is not common in travelers to southern Europe), Asia (not Southeast Asia), the Middle East, and Africa (particularly East and North Africa, with some cases elsewhere).

Clinical Presentation

Human Leishmaniasis encompasses multiple clinical syndromes, most notably visceral, cutaneous, and mucosal forms. Infections can result in two main forms of disease, cutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar). Different species can be associated with diverse clinical manifestations and sequelae. Species identification can facilitate clinical management, such as decisions regarding whether/which treatment is indicated. species, geographic location, and immune response of the host. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is characterized by one or more cutaneous lesions on areas where sandflies have fed. Persons who have cutaneous leishmaniasis have one or more sores on their skin. The sores can change in size and appearance over time. They often end up looking somewhat like a volcano, with a raised edge and central crater. A scab covers some sores. The sores can be painless or painful. Some people have swollen glands near the sores (for example, in the armpit if the sores are on the arm or hand).

Persons who have visceral leishmaniasis usually have fever, weight loss, and an enlarged spleen and liver (usually the spleen is bigger than the liver). Some patients have swollen glands. Certain blood tests are abnormal. For example, patients usually have low blood counts, including a low red blood cell count (anemia), low white blood cell count, and low platelet count. Some patients develop post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Visceral leishmaniasis is becoming an important opportunistic infection in areas where it coexists with HIV.

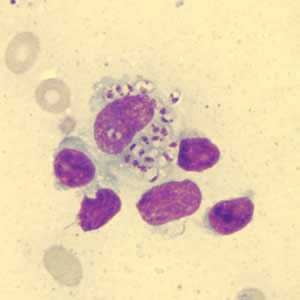

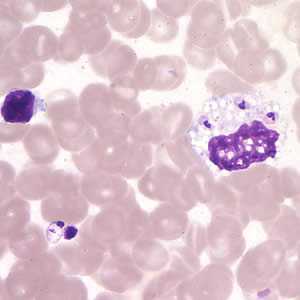

Leishmania amastigotes.

Figure A: Leishmania sp. amastigotes in a Giemsa-stained tissue scraping.

Figure B: Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis amastigotes in a Giemsa-stained tissue scraping. Identification to the species level is not possible based on morphology and other diagnostic techniques such isoenzyme assay or PCR are needed.

Figure C: Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis amastigotes in a Giemsa-stained tissue scraping.

Figure D: Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis amastigotes in a Giemsa-stained tissue scraping.

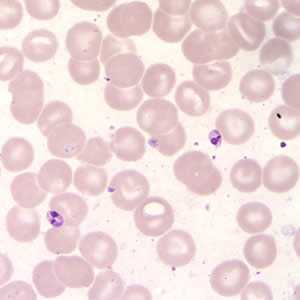

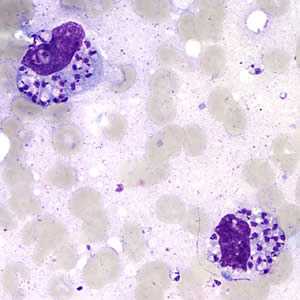

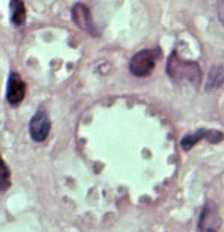

Leishmania amastigotes.

Figure A: Leishmania sp. amastigotes; touch-prep stained with Giemsa.

Figure B: Leishmania sp. amastigotes; touch-prep stained with Giemsa.

Figure C: Leishmania tropica amastigotes from an impression smear of a biopsy specimen from a skin lesion. In this figure, an intact macrophage is practically filled with amastigotes (arrows), several of which have a clearly visible nucleus and kinetoplast.

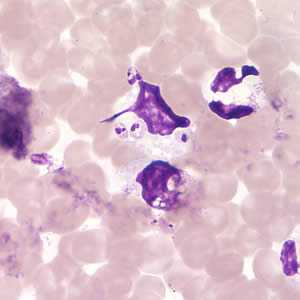

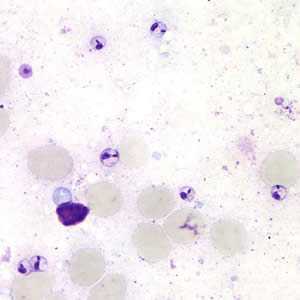

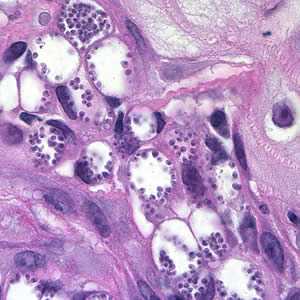

Leishmania mexicana in tissue stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure A: Amastigotes of Leishmania sp. in a biopsy specimen from a skin lesion, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure B: Leishmania mexicana in a biopsy specimen from a skin lesion stained with H&E. The amastigotes are lining the walls of two vacuoles, a typical arrangement. The species identification was derived from culture followed by isoenzyme analysis.

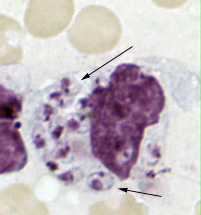

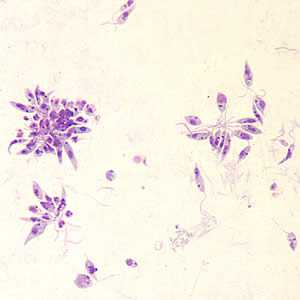

Leishmania sp. promastigotes from culture.

Figure A: Leishmania sp. promastigotes from culture.

Diagnostic Findings

Microscopy

In the human host, only the amastigotes stage is seen upon microscopic examination of tissue specimens. Amastigotes can be visualized with both Giemsa and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains. The amastigotes of Leishmania spp. are morphologically indistinguishable from those of Trypanosoma cruzi. Amastigotes are ovoid and measure 1-5 micrometers long by 1-2 micrometers wide. They possess both a nucleus and kinetoplast.

Isoenzyme analysis

Isolation can be done using the biphasic medium which includes a solid phase composed of blood agar base (e.g., NNN medium), with defribinated rabbit blood. After isolation parasites can be characterized to the complex and sometimes to the species level using isoenzyme analysis, which is the conventional diagnostic approach for Leishmania species identification. Diagnostic identification of Leishmania using this approach may take several weeks.

Serology

Antibody detection can prove useful in visceral leishmaniasis but is of limited value in cutaneous disease, since most patients do not develop a significant antibody response. In addition, cross reactivity can occur with Trypanosoma cruzi, a fact to consider when investigating Leishmania antibody response in patients who have been in Central or South America.

Molecular Diagnosis

Molecular approaches have the potential to be more sensitive and rapid; e.g., the results can be available within days versus weeks. CDC has incorporated molecular methods in the algorithm for the laboratory diagnosis of leishmaniasis. The method is based on PCR amplification using generic primers that amplify a segment of the rRNA internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) from multiple Leishmania species. DNA sequencing analysis is performed on the amplified fragment for species identification. This approach allows the differentiation among Viannia spp., namely, L. (V.) braziliensis, L. (V.) guyanensis, and L. (V.) panamensis as well as L. (L.) aethiopica, L. (L.) amazonensis, L. (L.) donovani, L. (L.) infantum/chagasi, (L.) major, L. (L.) mexicana and L. L. (L.) tropica

Newly Released

“Diagnosis and Treatment of Leishmaniasis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) ”

Treatment Information

General Points

The information provided here does not constitute a primer on treating leishmaniasis; rather, the focus is on basic principles and perspective, geared towards clinicians treating patients in the United States. Treatment decisions should be individualized, with expert consultation. In general, all clinically manifest cases of visceral leishmaniasis and mucosal leishmaniasis should be treated, whereas not all cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis require treatment.

The treatment approach depends in part on host and parasite factors. Some approaches/regimens are effective only against certain Leishmania species/strains and only in particular geographic regions. Even data from well-conducted clinical trials are not necessarily generalizable to other settings. Of particular note, data from the many clinical trials of therapy for visceral leishmaniasis in parts of India are not necessarily directly applicable to visceral leishmaniasis caused by L. donovani in other areas, to visceral leishmaniasis caused by other species, or to treatment of cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis.

Special groups (such as young children, elderly persons, pregnant/lactating women, and persons who are immunocompromised or who have other comorbidities) may need different medications or dosage regimens.

The relative merits of various treatment approaches/regimens can be discussed with CDC staff. In addition, in the United States, special considerations apply regarding the availability of particular medications to treat leishmaniasis. For example:

- Pentavalent antimonial (SbV) compounds—the traditional mainstays for treating leishmaniasis since the 1940s—are not licensed for U.S. commercial use. However, the SbV compound sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam®) is available to U.S.-licensed physicians through the CDC Drug Service (404-639-3670), under an IND (Investigational New Drug) protocol approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by CDC's Institutional Review Board. Although Pentostam® is not new or investigational, the IND mechanism makes it possible for CDC to stock and provide the drug in the United States. CDC's IND protocol covers intravenous (IV) and intramuscular (IM) administration (not intralesional). In the United States, the most common route of administration is IV (vs. IM), because the volume per dose is relatively high (for example, 14 mL for a 70-kg patient). Of note, Pentostam® is the only antileishmanial medication available through CDC.

- One parenteral agent, liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®), which is administered by IV infusion, is FDA-approved for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis per se (i.e., the approved indications do not include cutaneous or mucosal leishmaniasis). This approval for visceral leishmaniasis dates back to 1997.

- In March 2014, FDA approved the oral agent miltefosine

for treatment of cutaneous, mucosal, and visceral leishmaniasis caused by particular Leishmania species (see below for details), in adults and adolescents at least 12 years of age who weigh at least 30 kg (66 pounds). The FDA-approved treatment regimen for persons who weigh from 30 to 44 kg is as follows: one 50-mg oral capsule of miltefosine twice a day (total of 100 mg per day) for 28 consecutive days. The approved regimen for persons who weigh at least 45 kg (99 pounds) is one 50-mg capsule three times a day (total of 150 mg per day) for 28 consecutive days. Miltefosine is contraindicated in pregnant women. Women of reproductive potential should have a negative pregnancy test before starting therapy; they should be advised to use effective contraception during the treatment course and for 5 months thereafter. Nursing mothers should be advised not to breastfeed during the treatment course or for 5 months thereafter.

for treatment of cutaneous, mucosal, and visceral leishmaniasis caused by particular Leishmania species (see below for details), in adults and adolescents at least 12 years of age who weigh at least 30 kg (66 pounds). The FDA-approved treatment regimen for persons who weigh from 30 to 44 kg is as follows: one 50-mg oral capsule of miltefosine twice a day (total of 100 mg per day) for 28 consecutive days. The approved regimen for persons who weigh at least 45 kg (99 pounds) is one 50-mg capsule three times a day (total of 150 mg per day) for 28 consecutive days. Miltefosine is contraindicated in pregnant women. Women of reproductive potential should have a negative pregnancy test before starting therapy; they should be advised to use effective contraception during the treatment course and for 5 months thereafter. Nursing mothers should be advised not to breastfeed during the treatment course or for 5 months thereafter. - Some medications that might have merit for treating selected cases of leishmaniasis are available in the United States but the FDA-approved indications do not include leishmaniasis. Examples of such medications include the parenteral agents amphotericin B deoxycholate and pentamidine isethionate, as well as the orally administered "azoles" (ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole).

- Other medications that might have merit for treating selected cases of leishmaniasis currently are not available in the United States (such as the parenteral formulation of the aminoglycoside paromomycin)—or—are potentially available only through special mechanisms. For example, particular topical formations of paromomycin may be available through compounding pharmacies or may be imported under a single-use treatment protocol.

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

Decisions about whether and how to treat should be individualized. The treatment approach depends in part on the Leishmania species/strain and the geographic area in which infection was acquired; the natural history of infection, the risk for mucosal dissemination/disease, and the drug susceptibilities in the pertinent setting; and the number, size, location, evolution, and other clinical characteristics of the patient's skin lesions.

Therapy of cutaneous leishmaniasis may be indicated to:

- decrease the risk for mucosal dissemination/disease (particularly for New World species in the Viannia subgenus; see Disease)

- accelerate healing of the skin lesions

- decrease the risk for relapse (clinical reactivation) of the skin lesions

- decrease the local morbidity caused by large or persistent skin lesions, particularly those on the face or ears or near joints

- decrease the reservoir of infection in geographic areas where infected persons (vs. non-human animals) serve as reservoir hosts (such as in Kabul, Afghanistan, and other Leishmania tropica-endemic areas, where transmission is anthroponotic)

In general, the first sign of a therapeutic response to adequate treatment is decreasing induration (lesion flattening). The healing process for large, ulcerative lesions often continues after the end of therapy. Relapse (clinical reactivation) typically is noticed first at the margin of the lesion.

Systemic therapy (parenteral)

For pentavalent antimonial (SbV) therapy, see above about CDC's IND protocol for sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam®). The standard daily dose is 20 mg of SbV per kg, administered IV or IM. The traditional duration of therapy is 20 days for cutaneous leishmaniasis (10 days may suffice in some settings) and 28 days for mucosal (and visceral) leishmaniasis. For some patients, adjustment of the daily dose or the duration of therapy may be indicated.

Conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate traditionally has been used as rescue therapy for cutaneous (and mucosal) leishmaniasis. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B typically are better tolerated than conventional amphotericin B. However, the data supporting their use for treatment of cutaneous (and mucosal) leishmaniasis are anecdotal; standard dosage regimens have not been established. When lipid formulations (e.g., liposomal amphotericin B) have been used for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, patients typically have received 3 mg per kg daily, by IV infusion, for a total of 6 to 10 or more doses.

In the United States, pentamidine isethionate is uncommonly used for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Its limitations include the potential for irreversible toxicity and variable effectiveness.

Systemic therapy (oral)

In March 2014, FDA approved the oral agent miltefosine for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in adults and adolescents who are not pregnant or breastfeeding. The FDA-approved indications are limited to infection caused by three particular species, all three of which are New World species in the Viannia subgenus—namely, Leishmania (V.) braziliensis, L. (V.) panamensis, and L. (V.) guyanensis. Even for these species, the effectiveness of miltefosine has been variable in different geographic regions. Use of miltefosine for treatment of infection caused by other Leishmania species in the New World or by any species in the Old World would constitute off-label use, as would treatment of children less than 12 years of age. See above for additional perspective and considerations regarding miltefosine.

The "azoles" ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole—administered orally—have been used with mixed results, in various settings. For example:

- Ketoconazole (adult regimen: 600 mg daily for 28 days) showed modest activity against L. mexicana and L. (V.) panamensis infection in small studies in Guatemala and Panama, respectively. However, itraconazole (adult regimen: 200 mg twice daily for 28 days) was ineffective against L. (V.) panamensis infection in a clinical trial in Colombia.

- Use of fluconazole (adult regimen: 200 mg daily for 6 weeks) for treatment of L. major infection in various countries in the Old World has been associated with mixed results. Preliminary data from Iran suggest that a higher daily dose (400 vs. 200 mg) might be more effective against L. major infection. Preliminary, uncontrolled data from northeastern Brazil suggest that a regimen of 8 mg per kg daily for 4 to 6 weeks might be effective against L. (V.) braziliensis infection in that region.

Local therapy

Some cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis without risk for mucosal dissemination/disease might be candidates for local therapy, in part depending on the number, location, and characteristics of the skin lesions. Examples of local therapies that might have utility in some settings include cryotherapy (with liquid nitrogen), thermotherapy (use of localized current field radiofrequency heat), intralesional administration of SbV (to date, not covered by CDC's IND protocol for Pentostam®), and topical application of paromomycin (such as an ointment containing 15% paromomycin/12% methylbenzethonium chloride in soft white paraffin; not commercially available in the United States).

Visceral Leishmaniasis

The use of highly effective systemic therapy for leishmaniasis is important, as is supportive care—for example, therapy for malnutrition, anemia/bleeding, and intercurrent infections. For HIV-coinfected patients, antiretroviral therapy (ART) should be started or optimized according to standard practice; appropriate use of ART delays relapses and improves survival.

Liposomal amphotericin B is FDA-approved for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Although various regimens have been suggested in the published literature, the FDA-approved regimen for immunocompetent patients consists of 3 mg per kg daily, by IV infusion, on days 1–5, 14, and 21 (total dose of 21 mg/kg). The FDA-approved regimen for immunosuppressed patients consists of 4 mg per kg daily on days 1–5, 10, 17, 24, 31, and 38 (total dose of 40 mg/kg). Some immunosuppressed patients may need even higher total doses and/or secondary prophylaxis (chronic maintenance therapy), in particular, HIV-coinfected patients with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3. However, standard approaches to antileishmanial treatment and secondary prophylaxis have not been established—for example, the optimal agent, dose, and dosing interval for maintenance therapy.

Conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate is highly effective therapy for visceral leishmaniasis but generally is more toxic than liposomal amphotericin B. Immunocompetent patients typically receive 0.5 to 1.0 mg per kg—either daily or every other day—by IV infusion—for a total dose of approximately 15 to 20 mg per kg. Longer courses of therapy may be indicated for some patients.

Pentavalent antimonial (SbV) therapy generally remains highly effective in most regions, with the notable exception of parts of South Asia. See above about CDC's IND protocol for sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam®). The standard dosage regimen for immunocompetent patients consists of 20 mg of SbV per kg daily, IV or IM, for 28 days. For some patients, adjustment of the daily dose or the duration of therapy may be indicated.

Other parenteral agents that have merit in some settings include paromomycin sulfate (the chemical equivalent of aminosidine), which is not available for parenteral administration in the United States—and—pentamidine isethionate, a second-line agent whose limitations include suboptimal effectiveness (most notably, in parts of South Asia) and the potential for irreversible toxicity.

Miltefosine is considered the first highly active oral agent for visceral leishmaniasis. In March 2014, FDA approved miltefosine for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania donovani, in adults and adolescents who are not pregnant or breastfeeding. Use of miltefosine for visceral leishmaniasis caused by other species (e.g., L. infantum) would constitute off-label use, as would treatment of children less than 12 years of age. See above for additional perspective and considerations regarding miltefosine.

Newly Released

“Diagnosis and Treatment of Leishmaniasis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) ”

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir