Hookworm

[Ancylostoma braziliense] [Ancylostoma caninum] [Ancylostoma duodenale] [Necator americanus]

Causal Agent

The human hookworms include the nematode species, Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus. A larger group of hookworms infecting animals can invade and parasitize humans (A. ceylanicum) or can penetrate the human skin (causing cutaneous larva migrans), but do not develop any further (A. braziliense, A. caninum, Uncinaria stenocephala). Occasionally A. caninum larvae may migrate to the human intestine, causing eosinophilic enteritis. Ancylostoma caninum larvae have also been implicated as a cause of diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis.

Life Cycle

Intestinal Hookworm Infection

Eggs are passed in the stool  , and under favorable conditions (moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch in 1 to 2 days. The released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces and/or the soil

, and under favorable conditions (moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch in 1 to 2 days. The released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces and/or the soil  , and after 5 to 10 days (and two molts) they become filariform (third-stage) larvae that are infective

, and after 5 to 10 days (and two molts) they become filariform (third-stage) larvae that are infective  . These infective larvae can survive 3 to 4 weeks in favorable environmental conditions. On contact with the human host, the larvae penetrate the skin and are carried through the blood vessels to the heart and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed

. These infective larvae can survive 3 to 4 weeks in favorable environmental conditions. On contact with the human host, the larvae penetrate the skin and are carried through the blood vessels to the heart and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed  . The larvae reach the small intestine, where they reside and mature into adults. Adult worms live in the lumen of the small intestine, where they attach to the intestinal wall with resultant blood loss by the host

. The larvae reach the small intestine, where they reside and mature into adults. Adult worms live in the lumen of the small intestine, where they attach to the intestinal wall with resultant blood loss by the host  . Most adult worms are eliminated in 1 to 2 years, but the longevity may reach several years.

. Most adult worms are eliminated in 1 to 2 years, but the longevity may reach several years.

Some A. duodenale larvae, following penetration of the host skin, can become dormant (in the intestine or muscle). In addition, infection by A. duodenale may probably also occur by the oral and transmammary route. N. americanus, however, requires a transpulmonary migration phase.

Cutaneous Larval Migrans

Cutaneous larval migrans (also known as creeping eruption) is a zoonotic infection with hookworm species that do not use humans as a definitive host, the most common being A. braziliense and A. caninum. The normal definitive hosts for these species are dogs and cats. The cycle in the definitive host is very similar to the cycle for the human species. Eggs are passed in the stool  , and under favorable conditions (moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch in 1 to 2 days. The released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces and/or the soil

, and under favorable conditions (moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch in 1 to 2 days. The released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces and/or the soil  , and after 5 to 10 days (and two molts) they become filariform (third-stage) larvae that are infective

, and after 5 to 10 days (and two molts) they become filariform (third-stage) larvae that are infective  . These infective larvae can survive 3 to 4 weeks in favorable environmental conditions. On contact with the animal host

. These infective larvae can survive 3 to 4 weeks in favorable environmental conditions. On contact with the animal host  , the larvae penetrate the skin and are carried through the blood vessels to the heart and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed. The larvae reach the small intestine, where they reside and mature into adults. Adult worms live in the lumen of the small intestine, where they attach to the intestinal wall. Some larvae become arrested in the tissues, and serve as source of infection for pups via transmammary (and possibly transplacental) routes

, the larvae penetrate the skin and are carried through the blood vessels to the heart and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed. The larvae reach the small intestine, where they reside and mature into adults. Adult worms live in the lumen of the small intestine, where they attach to the intestinal wall. Some larvae become arrested in the tissues, and serve as source of infection for pups via transmammary (and possibly transplacental) routes  . Humans may also become infected when filariform larvae penetrate the skin

. Humans may also become infected when filariform larvae penetrate the skin  . With most species, the larvae cannot mature further in the human host, and migrate aimlessly within the epidermis, sometimes as much as several centimeters a day. Some larvae may persist in deeper tissue after finishing their skin migration.

. With most species, the larvae cannot mature further in the human host, and migrate aimlessly within the epidermis, sometimes as much as several centimeters a day. Some larvae may persist in deeper tissue after finishing their skin migration.

Geographic Distribution

Hookworm is the second most common human helminthic infection (after ascariasis). Hookworm species are worldwide in distribution, mostly in areas with moist, warm climate. Both N. americanus and A. duodenale are found in Africa, Asia and the Americas. Necator americanus predominates in the Americas and Australia, while only A. duodenale is found in the Middle East, North Africa and southern Europe.

Clinical Presentation

Iron deficiency anemia (caused by blood loss at the site of intestinal attachment of the adult worms) is the most common symptom of hookworm infection, and can be accompanied by cardiac complications. Gastrointestinal and nutritional/metabolic symptoms can also occur. In addition, local skin manifestations ('ground itch') can occur during penetration by the filariform (L3) larvae, and respiratory symptoms can be observed during pulmonary migration of the larvae.

The most common manifestation of zoonotic infection with animal hookworm species is cutaneous larva migrans, also known as ground itch, where migrating larvae cause an intensely pruritic serpiginous track in the upper dermis. Less commonly, larvae may migrate to the bowel lumen and cause an eosinophilic enteritis. In some cases of diffuse unilateral subacute retinitis, single larvae compatible in size to A. caninum have been visualized in the affected eye.

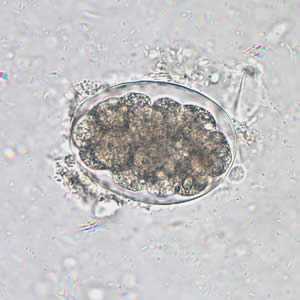

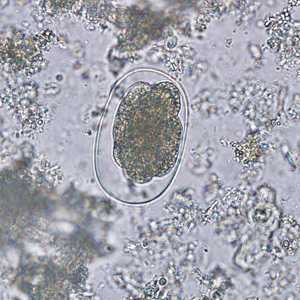

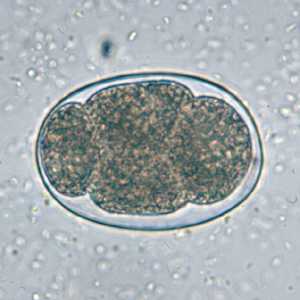

Hookworm eggs.

Figure A: Hookworm egg in an unstained wet mount, taken at 400x magnification.

Figure B: Hookworm egg in an unstained wet mount, taken at 400x magnification.

Figure C: Hookworm egg in an unstained wet mount.

Figure D: Hookworm egg in an unstained wet mount.

Figure E: Hookworm egg in a wet mount.

Figure F: Hookworm egg in a wet mount under UV fluorescence microscopy; image taken at 200x magnification.

Hookworm rhabditiform larva.

Figure A: Hookworm rhabditiform larva (wet preparation).

Figure B: Hookworm rhabditiform larva (wet preparation).

Hookworm filariform larva.

Figure A: Filariform (L3) hookworm larva.

Figure B: Filariform (L3) hookworm larva.

Figure C: Filariform (L3) hookworm larva in a wet mount..

Figure D: Close-up of the posterior end of a filariform (L3) hookworm larva.

Adult hookworms.

Figure A: Adult worm of Ancylostoma duodenale. Anterior end is depicted showing cutting teeth.

Figure B: Adult worm of Necator americanus. Anterior end showing mouth parts with cutting plates.

Figure C: Anterior end of an adult of Ancylostoma caninum, a dog parasite that has been found to produce a rare human infection known as eosinophilic enteritis.

Figure D: Anterior end of an adult female Ancylostoma sp.

Figure E: Posterior end of the worm seen in Figure D.

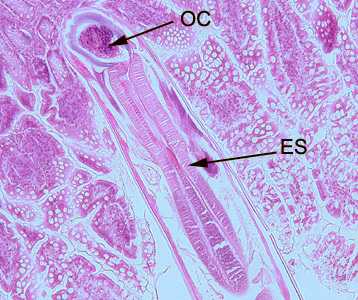

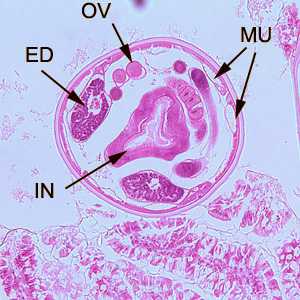

Hookworms in tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure A: Longitudinal section of an adult hookworm worm in a bowel biopsy, stained with H&E. Note the oral cavity (OC) and strong, muscled esophagus (ES).

Figure B: Cross-section of an adult hookworm from the same specimen in Figure A. Shown here are the platymyarian musculature (MU), intestine with brush border (IN), excretory ducts (ED), and coiled ovaries (OV).

Figure C: Another-cross section of the specimen in Figures A and B.

Diagnostic Findings

Microscopic identification of eggs in the stool is the most common method for diagnosing hookworm infection. The recommended procedure is as follows:

- Collect a stool specimen.

- Fix the specimen in 10% formalin.

- Concentrate using the formalin–ethyl acetate sedimentation technique.

- Examine a wet mount of the sediment.

Where concentration procedures are not available, a direct wet mount examination of the specimen is adequate for detecting moderate to heavy infections. For quantitative assessments of infection, various methods such as the Kato-Katz can be used.

Cutaneous larval migrans is usually diagnosed clinically, as there are no serologic tests for zoonotic hookworm infections. Larvae may be seen in stained tissue sections, but this procedure is usually not recommended as the parasites are usually not found in the visible track.

More on: Morphologic comparison with other intestinal parasites

Examination of the eggs cannot distinguish between N. americanus and A. duodenale. Larvae can be used to differentiate between N. americanus and A. duodenale, by rearing filariform larvae in a fecal smear on a moist filter paper strip for 5 to 7 days (Harada-Mori). Occasionally, it may be necessary to distinguish between the rhabditiform larvae (L1) of hookworms and those of Strongyloides stercoralis.

Treatment Information

Treatment

Hookworm infection is treated with albendazole, mebendazole, or pyrantel pamoate. Dosage is the same for children as for adults. Albendazole should be taken with food. Albendazole is not FDA-approved for treating hookworm infection.

| Drug | Dosage for adults and children |

|---|---|

| Albendazole | 400 mg orally once |

| Mebendazole | 100 mg orally twice a day for 3 days or 500 mg orally once |

| Pyrantel pamoate | 11 mg/kg (up to a maximum of 1 g) orally daily for 3 days |

Albendazole

Oral albendazole is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

Mebendazole

Mebendazole is available in the United States only through compounding pharmacies.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

Pyrantel Pamoate

Pyrantel pamoate is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir