Gnathostomiasis

[Gnathostoma hispidum][Gnathostoma spinigerum]

Causal Agent

The nematodes (roundworms) Gnathostoma spinigerum (Asia, Africa and Australia), Gnathostoma hispidum (Asia and Australia), Gnathostoma nipponicum (Japan only), Gnathostoma doloresi (Asia) and Gnathostoma binucleatum (Mexico, Central and South America only), which infect vertebrate animals. Gnathostoma malaysiae has also been implicated as causing human disease, but this is yet to be confirmed. Human gnathostomiasis is due to migrating immature worms.

Life Cycle

Adapted from a drawing provided by Dr. Sylvia Paz Díaz Camacho, Universidade Autónoma de Sinaloa, Mexico.

In the natural definitive host (pigs, cats, dogs, wild animals) the adult worms reside in a tumor which they induce in the gastric wall. They deposit eggs that are unembryonated when passed in the feces  . Eggs become embryonated in water, and eggs release first-stage larvae

. Eggs become embryonated in water, and eggs release first-stage larvae . If ingested by a small crustacean (Cyclops, first intermediate host), the first-stage larvae develop into second-stage larvae

. If ingested by a small crustacean (Cyclops, first intermediate host), the first-stage larvae develop into second-stage larvae . Following ingestion of the Cyclops by a fish, frog, or snake (second intermediate host), the second-stage larvae migrate into the flesh and develop into third-stage larvae

. Following ingestion of the Cyclops by a fish, frog, or snake (second intermediate host), the second-stage larvae migrate into the flesh and develop into third-stage larvae . When the second intermediate host is ingested by a definitive host the third-stage larvae develop into adult parasites in the stomach wall

. When the second intermediate host is ingested by a definitive host the third-stage larvae develop into adult parasites in the stomach wall . Alternatively, the second intermediate host may be ingested by the paratenic host (animals such as birds, snakes, and frogs) in which the third-stage larvae do not develop further but remain infective to the next predator

. Alternatively, the second intermediate host may be ingested by the paratenic host (animals such as birds, snakes, and frogs) in which the third-stage larvae do not develop further but remain infective to the next predator . Humans become infected by eating undercooked fish or poultry containing third-stage larvae, or reportedly by drinking water containing infective second-stage larvae in Cyclops

. Humans become infected by eating undercooked fish or poultry containing third-stage larvae, or reportedly by drinking water containing infective second-stage larvae in Cyclops .

.

Geographic Distribution

Most human cases have been reported from Asia (especially Thailand and Japan) and Mexico.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical manifestations in human gnathostomiasis are caused by migration of the immature worms (L3s). Migration in the subcutaneous tissues causes intermittent, migratory, painful, pruritic swellings (cutaneous larva migrans). Migration to other tissues (visceral larva migrans), can result in cough, hematuria, and ocular involvement, with the most serious manifestations eosinophilic meningitis with myeloencephalitis. High eosinophilia is present.

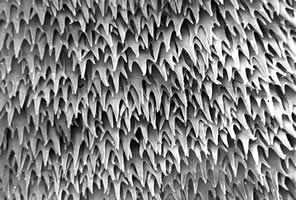

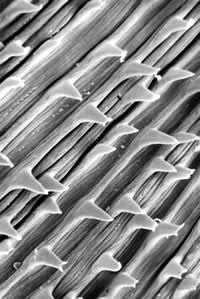

Head bulb and cuticular spines.

Figure A: Head bulb.

Figure B: Cuticular spines of the posterior body part.

Detail of cuticular spines of the anterior body part.

Figure A: Detail of cuticular spines of the anterior body part.

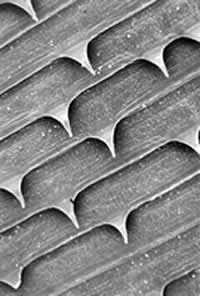

Detail of nondendiculated cuticular spines.

Figure A: Detail of nondendiculated cuticular spines.

Figure B: Detail of nondendiculated cuticular spines.

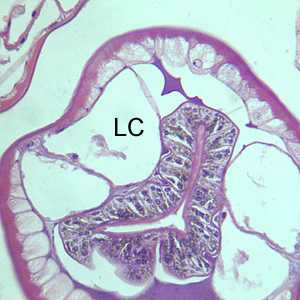

Cross-sections of Gnathostoma sp. stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure A: Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained cross-section of Gnathostoma sp., taken from a subcutaneous nodule above the right breast of a patient, showing the esophagus. Note the presence of cuticular spines (arrow). Image courtesy of Diagnostix Pathology Laboratories LTD, Canossa Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Figure B: Another H&E-stained cross-section of Gnathostoma sp., taken of the same specimen in Figure A, showing the intestinal cells and characteristic large lateral chords (LC). Note the multinucleate intestinal cells and the presence of pigmented granular material in the intestinal cells.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Morphologic Diagnosis

Morphologic diagnosis of human gnathostomiasis is made by the examination of larval worms in biopsy specimens.

Antibody Detection

Currently there are no serologic tests available for gnathostomiasis at the CDC nor in the U.S. Please contact DPDx for the contact information for labs in Thailand and Japan that perform this test.

Treatment Information

For cutaneous symptoms of Gnathostoma infection, both albendazole and ivermectin have been shown to result in cure in several trials that were too small to firmly establish efficacy and safety of treatment.

Reported cure rates at 6 months after treatment with albendazole are >90% and after treatment with ivermectin range from 76–95.2%. Albendazole may cause outward migration of larvae. Ivermectin may cause a temporary increase of cutaneous symptoms. Two small studies in which patients were followed up for 1 year or longer found cure rates after treatment with albendazole decreased over time. Relapse is not uncommon, however, with either treatment and has been shown to occur up to 26 months after initial therapy. Monitoring for symptom recurrence is needed for all patients regardless of treatment regimen. Relapse does not necessarily require treatment with a different medication, though data on this issue also are limited.

Two different regimens of albendazole (400 mg daily for 21 days and 400 mg twice daily for 21 days) and two different regimens of ivermectin (200 mcg/kg once daily for 1 day and 200 mcg/kg once daily for 2 days) have been studied. Data are insufficient to determine which regimen is the most effective, so it would probably be prudent to use the higher dose regimen of either medication until better data are available.

Whether to treat ocular and central nervous system (CNS) Gnathostoma infection remains controversial, particularly as there are no published studies of the efficacy of albendazole or ivermectin. As albendazole may cause larvae to migrate and ivermectin may cause a disease flare, there is concern that treatment with antihelminthics could worsen a patient’s neurologic status and possibly increase the risk for death or permanent neurologic deficit. There has been only one observational study of corticosteroids in patients presenting with probable Gnathostoma infection. No benefit of corticosteroids was demonstrated, possibly because it is thought that much of the damage to the CNS is caused by mechanical destruction of tissue.

At this time it is not possible to give recommendations for the treatment of CNS or ocular disease other than to provide supportive care. As gnathostomiasis has been shown to cause intracranial hemorrhage, patients with neurologic disease should be carefully monitored and plans for prompt intervention should be put into place.

Ivermectin

Oral ivermectin is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: July 6, 2017

- Page last updated: July 6, 2017

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir