Fasciolopsiasis

[Fasciolopsis buski]

Causal Agents

The trematode Fasciolopsis buski, the largest intestinal fluke of humans.

Life Cycle

Immature eggs are discharged into the intestine and stool . Eggs become embryonated in water

. Eggs become embryonated in water  , eggs release miracidia

, eggs release miracidia  , which invade a suitable snail intermediate host

, which invade a suitable snail intermediate host  . In the snail the parasites undergo several developmental stages (sporocysts

. In the snail the parasites undergo several developmental stages (sporocysts  , rediae

, rediae , and cercariae

, and cercariae  ). The cercariae are released from the snail

). The cercariae are released from the snail  and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic plants

and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic plants  . The mammalian hosts become infected by ingesting metacercariae on the aquatic plants. After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum

. The mammalian hosts become infected by ingesting metacercariae on the aquatic plants. After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum  and attach to the intestinal wall. There they develop into adult flukes (20 to 75 mm by 8 to 20 mm) in approximately 3 months, attached to the intestinal wall of the mammalian hosts (humans and pigs)

and attach to the intestinal wall. There they develop into adult flukes (20 to 75 mm by 8 to 20 mm) in approximately 3 months, attached to the intestinal wall of the mammalian hosts (humans and pigs)  . The adults have a life span of about one year.

. The adults have a life span of about one year.

Geographic Distribution

Asia and the Indian subcontinent, especially in areas where humans raise pigs and consume freshwater plants.

Clinical Presentation

Most infections are light and asymptomatic. In heavier infections, symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, ascites, anasarca and intestinal obstruction.

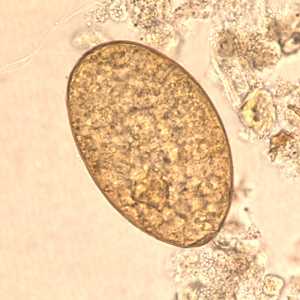

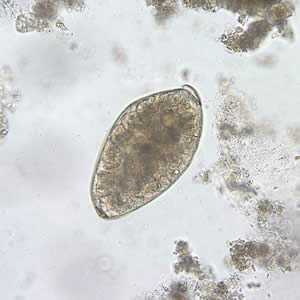

Fasciolopsis buski eggs.

Figure A: Egg of F. buski in a unstained wet mount.

Figure B: Egg of F. buski in a unstained wet mount.

Figure C: Egg of F. buski in unstained wet mounts.

Figure D: Egg of F. buski in an unstained wet mount of stool.

Figure E: Higher magnification (400x) of the egg in Figure D.

Fasciolopsis buski adults.

Figure B: Adult fluke of F. buski.

Figure A: Adult fluke of F. buski. Image contributed by Georgia Division of Public Health.

Intermediate hosts of F. buski.

Figure A: Snail in the genus Hippeutis, an intermediate host for F. buski. Image courtesy of Conchology, Inc, Mactan Island, Philippines.

Figure B: Snail in the genus Segmentina, an intermediate host for F. buski. Image courtesy of Conchology, Inc, Mactan Island, Philippines.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Microscopic identification of eggs, or more rarely of the adult flukes, in the stool or vomitus is the basis of specific diagnosis. The eggs are indistinguishable from those of Fasciola hepatica.

Morphology

Treatment Information

Praziquantel , adults, 75 mg/kg/day orally in three divided doses for 1 day; the dosage for children is the same.

(Note: praziquantel should be taken with liquids during a meal.)

*Not FDA-approved for this indication

Praziquantel

Oral praziquantel is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

References

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. The drugs we have and the drugs we need against major helminth infections. Adv Parasitol 2010;73:197-230.

- Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Intapan PM, Maleewong W, Brindley PJ. Food-borne trematodiases in Southeast Asia epidemiology, pathology, clinical manifestation and control. Adv Parasitol 2010;72:305-50.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. Food-borne tremadodiases. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009;22:466-83.

- WHO, 2009. WHO Model Formulary. In: World Health Organization. WHO Press, Geneva.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. Chemotherapy for major food-borne trematodes: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2004; 5: 1711–26.

- Graczyk TK, Gilman RH, Fried B. Fasciolopsiasis: is it a controllable food-borne disease? Parasitol Res 2001;87:80-3.

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir