Fascioliasis

[Fasciola gigantica] [Fasciola hepatica]

Causal Agent

The trematodes Fasciola hepatica (the sheep liver fluke) and Fasciola gigantica, parasites of herbivores that can infect humans accidentally.

Life Cycle

Immature eggs are discharged in the biliary ducts and in the stool  . Eggs become embryonated in water

. Eggs become embryonated in water  , eggs release miracidia

, eggs release miracidia  , which invade a suitable snail intermediate host

, which invade a suitable snail intermediate host  , including the genera Galba, Fossaria and Pseudosuccinea. In the snail the parasites undergo several developmental stages (sporocysts

, including the genera Galba, Fossaria and Pseudosuccinea. In the snail the parasites undergo several developmental stages (sporocysts  , rediae

, rediae  , and cercariae

, and cercariae  ). The cercariae are released from the snail

). The cercariae are released from the snail  and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic vegetation or other surfaces. Mammals acquire the infection by eating vegetation containing metacercariae. Humans can become infected by ingesting metacercariae-containing freshwater plants, especially watercress

and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic vegetation or other surfaces. Mammals acquire the infection by eating vegetation containing metacercariae. Humans can become infected by ingesting metacercariae-containing freshwater plants, especially watercress  . After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum

. After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum  and migrate through the intestinal wall, the peritoneal cavity, and the liver parenchyma into the biliary ducts, where they develop into adults

and migrate through the intestinal wall, the peritoneal cavity, and the liver parenchyma into the biliary ducts, where they develop into adults  . In humans, maturation from metacercariae into adult flukes takes approximately 3 to 4 months. The adult flukes (Fasciola hepatica: up to 30 mm by 13 mm; F. gigantica: up to 75 mm) reside in the large biliary ducts of the mammalian host. Fasciola hepatica infect various animal species, mostly herbivores.

. In humans, maturation from metacercariae into adult flukes takes approximately 3 to 4 months. The adult flukes (Fasciola hepatica: up to 30 mm by 13 mm; F. gigantica: up to 75 mm) reside in the large biliary ducts of the mammalian host. Fasciola hepatica infect various animal species, mostly herbivores.

Geographic Distribution

Fascioliasis occurs worldwide. Human infections with F. hepatica are found in areas where sheep and cattle are raised, and where humans consume raw watercress, including Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Infections with F. gigantica have been reported, more rarely, in Asia, Africa, and Hawaii.

Clinical Presentation

During the acute phase (caused by the migration of the immature fluke through the hepatic parenchyma), manifestations include abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, urticaria and eosinophilia, and can last for months. In the chronic phase (caused by the adult fluke within the bile ducts), the symptoms are more discrete and reflect intermittent biliary obstruction and inflammation. Occasionally, ectopic locations of infection (such as intestinal wall, lungs, subcutaneous tissue, and pharyngeal mucosa) can occur.

Fasciola hepatica eggs.

Figure A: Egg of F. hepatica in an unstained wet mount, taken at 400x magnification.

Figure B: Egg of F. hepatica in an unstained wet mount, taken at 400x magnification.

Figure C: Egg of F. hepatica in an unstained wet mount.

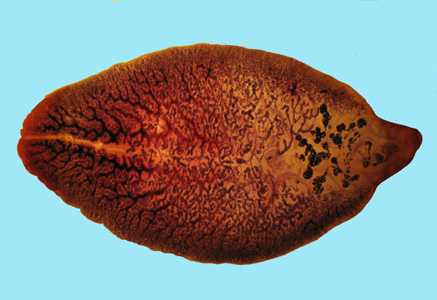

F. hepatica adults.

Figure A: Unstained adult of F. hepatica fixed in formalin.

Figure B: Adult of F. hepatica stained with carmine.

F. hepatica adults observed in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Figure A: Adult of F. hepatica observed with ERCP imaging in the common bile duct of a human patient. Image courtesy of Dr. Subhash Agal, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, Mumbai, India.

Figure B: Adult of F. hepatica observed with ERCP imaging in the common bile duct of a human patient. Image courtesy of Dr. Subhash Agal, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, Mumbai, India.

Intermediate hosts of Fasciola spp.

Figure A: Galba truncatula, the main intermediate host of F. hepatica throughout most of the fluke's natural range in Europe and western Asia. Image courtesy of Conchology, Inc, Mactan Island, Philippines.

Figure B: Galba humilis, a host of F. hepatica in Canada and parts of the United States. Image courtesy of Conchology, Inc, Mactan Island, Philippines.

Figure C: Fossaria bulamoides, a host for F. hepatica in the western United States. Image courtesy of Conchology, Inc, Mactan Island, Philippines.

Figure D: Pseudosuccinea columella, a lymnaeid snail that has been introduced into South America and serves as an intermediate host for F. hepatica in Venezuela and Colombia. Image courtesy of Conchology, Inc, Mactan Island, Philippines.

Diagnostic Findings

Microscopic identification of eggs is useful in the chronic (adult) stage. Eggs can be recovered in the stools or in material obtained by duodenal or biliary drainage. They are morphologically indistinguishable from those of Fasciolopsis buski. False fascioliasis (pseudofascioliasis) refers to the presence of eggs in the stool resulting not from an actual infection but from recent ingestion of infected livers containing eggs. This situation (with its potential for misdiagnosis) can be avoided by having the patient follow a liver-free diet several days before a repeat stool examination. Antibody detection tests are useful especially in the early invasive stages, when the eggs are not yet apparent in the stools, or in ectopic fascioliasis.

Antibody Detection

The acute manifestations of human fascioliasis may precede the appearance of eggs in the stool by several weeks; immunodiagnostic tests may be useful for early indication of Fasciola infection as well as for confirmation of chronic fascioliasis when egg production is low or sporadic and for ruling out “pseudofascioliasis” associated with ingestion of parasite eggs in sheep or calves’ liver. The current tests of choice for immunodiagnosis of human Fasciola hepatica infection are enzyme immunoassays (EIA) with excretory-secretory (ES) antigens combined with confirmation of positives by immunoblot. Specific antibodies to Fasciola may be detectable within 2 to 4 weeks after infection, which is 5 to 7 weeks before eggs appear in stool. Sensitivity for the FAST-ELISA format of EIA was reported to be 95%, while sensitivity for the immunoblot using 12-, 17-, and 63-kDa antigens appeared to be 100%. However, some cross-reactivity occurs in the FAST-ELISA with serum specimens of patients with schistosomiasis. Antibody levels decrease to normal 6 to 12 months after chemotherapeutic cure and can be used to predict the success of therapy. CDC has developed an immunoblot assay for fascioliasis based on a recombinant F. hepatica antigen (FhSAP2). A positive reaction is defined if a band at ~ 38 kDa is present. The sensitivity of the assay is ≥ 94% (16/17) and specificity is ≥ 98% (113/115) for human with chronic fascioliasis. Currently we don’t have any information on the performance of this assay on acute fascioliasis cases.

Please note: Serologic testing for fascioliasis is available at the CDC. Pre-approval is necessary before submitting a specimen for fascioliasis testing. To obtain approval please contact the Parasitic Diseases Public Inquiries at (404) 718 4745 or at parasites@cdc.gov.

References:

Shin SH et al. Development of Two FhSAP2 Recombinant-Based Assays for Immunodiagnosis of Human Chronic Fascioliasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 2016: 95(4), pp. 852-855.

Hillyer GV. Serological diagnosis of Fasciola hepatica. Parasitol al Dia 1993;17:130-6.

Treatment Information

Triclabendazole is the drug of choice for treatment of fascioliasis. It is the medication recommended by the World Health Organization. It is not yet widely available to treat people. In the United States, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration. However, it is available through CDC, under an investigational protocol.

As with all medications, use of triclabendazole should be individualized. It is a benzimidazole compound that is active against immature and adult Fasciola parasites. The therapy usually is effective and safe. Triclabendazole is given orally, with food, to improve absorption.

The medication comes in scored tablets. The dosage is calculated on the basis of the patient’s weight. The typical regimen is a single oral dose of 10 mg of triclabendazole per kilogram of body weight (10 mg/kg).

Two-dose (double-dose) triclabendazole therapy can be given to patients who have severe or heavy Fasciola infections (many parasites) or who did not respond to single-dose therapy. Of note, some experts routinely use 2-dose therapy, which might have a higher response rate, on the basis of limited data.

Two-dose therapy means that the patient is given 2 individual doses of 10 mg/kg, separated in time by 12 to 24 hours. In other words, the patient receives a total dose of 20 mg/kg, given in 2 divided doses, 12 to 24 hours apart.

Triclabendazole

Triclabendazole is not commercially available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: June 8, 2017

- Page last updated: June 14, 2017

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir