Roussy–Lévy syndrome

Roussy–Lévy syndrome, also known as Roussy–Lévy hereditary areflexic dystasia, is a rare genetic disorder of humans that results in progressive muscle wasting. It is caused by mutations in the genes that code for proteins necessary for the functioning of the myelin sheath of the neurons, affecting the conductance of nerve signals and resulting in loss of muscles' ability to move.

| Roussy–Lévy syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

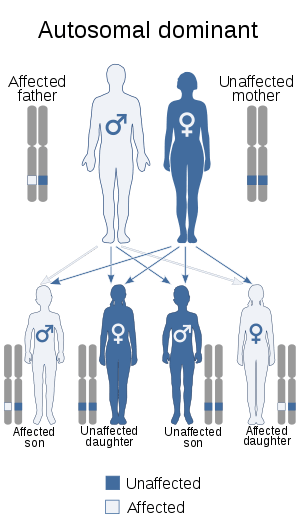

| This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

The condition affects people from infants through adults and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Currently, no cure is known for the disorder.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of the Roussy–Lévy syndrome mainly stem from nerve damage and the resulting progressive muscle atrophy. Neurological damage may result in absent tendon reflexes (areflexia), some distal sensory loss and decreased excitability of muscles to galvanic and faradic stimulation. Progressive muscle wasting results in weakness of distal limb muscles (especially the peronei), gait ataxia, pes cavus, postural tremors and static tremor of the upper limbs, kyphoscoliosis, and foot deformity.[1]

These symptoms frequently translate into delayed onset of ability to walk, loss of coordination and balance, foot drop, and foot-bone deformities. They are usually first observed during infancy or early childhood, and slowly progress until about age 30, at which point progression may stop in some individuals, or symptoms may continue to slowly progress.[2]

Causes

The Roussy–Lévy syndrome has been associated with two genetic mutations: a duplication of the PMP22 gene that carries the instructions for producing the peripheral myelin protein 22, a critical component of the myelin sheath; and a missense mutation in the MPZ gene which codes for myelin protein zero, a major structural protein of peripheral myelin.[3][4][1][5]

As PMP22 mutations are also associated with Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 1A and MPZ mutations are associated with Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 1B, it remains the subject of discussion whether the Roussy–Lévy syndrome is a separate entity or a specific phenotype of either disorder.[4]

Pathophysiology

In common with other types of Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, neurological examination reveals decreased nerve conduction velocity and histologic features of a hypertrophic demyelinating neuropathy.[6] Electromyography shows signs of mild neurogenic damage[5][7] while nerve biopsy shows onion bulb formations; the appearance of these formations is what primarily led Gustave Roussy and Gabrielle Lévy, the scientists who first described the disorder, to classify it as a variant of Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease.[4]

To create a working nerve, neurons, Schwann cells, and fibroblasts must work together. Molecular signals are exchanged between Schwann cells and neurons to regulate survival and differentiation of a nerve. However, these signals are disrupted in patients with the Roussy–Lévy syndrome.

Diagnosis

While the clinical picture may point towards the diagnosis of the Roussy–Lévy syndrome, the condition can only be confirmed with absolute certainty by carrying out genetic testing in order to identify the underlying mutations.

Treatment and management

There is no pharmacological treatment for Roussy–Lévy syndrome.

Treatment options focus on palliative care and corrective therapy. Patients tend to benefit greatly from physical therapy (especially water therapy as it does not place excessive pressure on the muscles), while moderate activity is often recommended to maintain movement, flexibility, muscle strength and endurance.[3]

Patients with foot deformities may benefit from corrective surgery, which, however, is usually a last resort. Most such surgeries include straightening and pinning the toes, lowering the arch, and sometimes, fusing the ankle joint to provide stability. Recovering from these surgeries is oftentimes long and difficult. Proper foot care including custom-made shoes and leg braces may minimize discomfort and increase function.[4][8]

While no medicines are reported to treat the disorder, patients are advised to avoid certain medications as they may aggravate the symptoms.

Prognosis

The Roussy–Lévy syndrome is not a fatal disease and life expectancy is normal. However, due to progressive muscle wasting patients may need supportive orthopaedic equipment or wheelchair assistance.[4]

History

In 1926, scientists Gustave Roussy and Gabrielle Lévy reported 7 cases within a same family of a dominantly inherited disorder over 4 generations.[4] They noticed that prominent features of this disorder were an unsteady gait during early childhood and areflexia, or the absence of reflexes, which eventually led to clumsiness and muscle weakness. During a nerve biopsy of a few of the original patients, the demyelinating lesions found led the scientists to believe that the Roussy–Lévy syndrome was a variant of demyelinating Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT-1).[4]

References

- Zubair, S.; Holland, N. R.; Beson, B.; Parke, J. T.; Prodan, C. I. (2008). "A novel point mutation in the PMP22 gene in a family with Roussy-Levy syndrome". Journal of Neurology. 255 (9): 1417–1418. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-0896-5. PMID 18592125.

- Haubrich, C.; Krings, T.; Senderek, J.; Züchner, S.; Schröder, J.; Noth, J.; Töpper, R. (2002). "Hypertrophic nerve roots in a case of Roussy-Lévy syndrome". Neuroradiology. 44 (11): 933–937. doi:10.1007/s00234-002-0847-2. PMID 12428130.

- Auer-Grumbach, M.; Strasser-Fuchs, S.; Wagner, K.; Körner, E.; Fazekas, F. (1998). "Roussy–Lévy syndrome is a phenotypic variant of Charcot–Marie–Tooth syndrome IA associated with a duplication on chromosome 17p11.2". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 154 (1): 72–75. doi:10.1016/S0022-510X(97)00218-9. PMID 9543325.

- Planté-Bordeneuve, V.; Guiochon-Mantel, A.; Lacroix, C.; Lapresle, J.; Said, G. (1999). "The Roussy-Lévy family: from the original description to the gene". Annals of Neurology. 46 (5): 770–773. doi:10.1002/1531-8249(199911)46:5<770::AID-ANA13>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 10553995.

- Thomas, P. (1997). "The phenotypic manifestations of chromosome 17p11.2 duplication". Brain. 120 (3): 465–478. doi:10.1093/brain/120.3.465.

- Sturtz, F. G.; Chauvin, F.; Ollagnon-Roman, E.; Bost, M.; Latour, P.; Bonnebouche, C.; Gonnaud, P. M.; Bady, B.; Chazot, G.; Vandenberghe, A. (1996). "Modelization of Motor Nerve Conduction Velocities for Charcot-Marie-Tooth (Type-1) Patients". European Neurology. 36 (4): 224–228. doi:10.1159/000117254. PMID 8814426.

- Dupré, N.; Bouchard, J. P.; Cossette, L.; Brunet, D.; Vanasse, M.; Lemieux, B.; Mathon, G.; Puymirat, J. (1999). "Clinical and electrophysiological study in French-Canadian population with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A associated with 17p11.2 duplication" (PDF). The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 26 (3): 196–200. PMID 10451742.

- Thomas, P. K. (1999). "Overview of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1A". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 883: 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08560.x. PMID 10586223.