Pes cavus

Pes cavus, also known as high arch, is a human foot type in which the sole of the foot is distinctly hollow when bearing weight. That is, there is a fixed plantar flexion of the foot. A high arch is the opposite of a flat foot and is somewhat less common.

| Pes cavus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | High instep, high arch, talipes cavus, cavoid foot, supinated foot |

| |

| High arch in foot of a person with a hereditary neuropathy | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics, Podiatry |

Signs and symptoms

Pain and disability

As with certain cases of flat feet, high arches may be painful due to metatarsal compression; however, high arches— particularly if they are flexible or properly cared-for—may be an asymptomatic condition.

People with pes cavus sometimes—though not always—have difficulty finding shoes that fit and may require support in their shoes. Children with high arches who have difficulty walking may wear specially-designed insoles, which are available in various sizes and can be made to order.

Individuals with pes cavus frequently report foot pain, which can lead to a significant limitation in function. The range of complaints reported in the literature include metatarsalgia, pain under the first metatarsal, plantar fasciitis, painful callosities, ankle arthritis, and Achilles tendonitis.[1]

There are many other symptoms believed to be related to the cavus foot. These include shoe-fitting problems,[2] lateral ankle instability,[3] lower limb stress fractures,[4] knee pain,[5] iliotibial band friction syndrome,[6] back pain [7] and tripping.[8]

Foot pain in people with pes cavus may result from abnormal plantar pressure loading because, structurally, the cavoid foot is regarded as being rigid and non-shock absorbent and having reduced ground contact area. There have previously been reports of an association between excessive plantar pressure and foot pathology in people with pes cavus.[9]

Cause

Pes cavus may be hereditary or acquired, and the underlying cause may be neurological, orthopedic, or neuromuscular. Pes cavus is sometimes—but not always—connected through Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathy Type 1 (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease) and Friedreich's Ataxia; many other cases of pes cavus are natural.

The cause and deforming mechanism underlying pes cavus is complex and not well understood. Factors considered influential in the development of pes cavus include muscle weakness and imbalance in neuromuscular disease, residual effects of congenital clubfoot, post-traumatic bone malformation, contracture of the plantar fascia, and shortening of the Achilles tendon.[10]

Among the cases of neuromuscular pes cavus, 50% have been attributed to Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, CMT,[11] which is the most common type of inherited neuropathy with an incidence of 1 per 2,500 persons affected.[12] Also known as Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathy (HMSN), it is genetically heterogeneous and occasionally idiopathic. (See CMT Association website) There are many different types and subtypes of CMT, and as a result, it can present from infancy through to adulthood. CMT is a peripheral neuropathy, effecting the distal muscles first as weakness, clumsiness, and frequent falls. It usually effects the feet first, but can sometimes begin in the hands. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease can cause painful foot deformities such as pes cavus. Although it is a relatively common disease, many doctors and laypersons are not familiar with it. There are no cures or effective courses of treatment to halt the progression of any form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease at this time.[13]

The development of the cavus foot structure seen in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease has been previously linked to an imbalance of muscle strength around the foot and ankle. A hypothetical model proposed by various authors describes a relationship whereby weak evertor muscles are overpowered by stronger invertor muscles, causing an adducted forefoot and inverted rearfoot. Similarly, weak dorsiflexors are overpowered by stronger plantarflexors, causing a plantarflexed first metatarsal and anterior pes cavus.[14]

Pes cavus is also evident in people without neuropathy or other neurological deficit. In the absence of neurological, congenital, or traumatic causes of pes cavus, the remaining cases are classified as being ‘idiopathic’ because their aetiology is unknown.[15]

Diagnosis

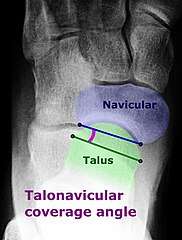

On weightbearing projectional radiography, pes cavus can be diagnosed and graded by several features, the most important being medial peritalar subluxation, increased calcaneal pitch (variable) and abnormal talar-1st metatarsal angle (Meary's angle).[16] Medial peritalar subluxation can be demonstrated by a medially rotated talonavicular coverage angle.[16]

Dorsoplantar projectional radiograph of the foot showing the measurement of the talonavicular coverage angle.

Dorsoplantar projectional radiograph of the foot showing the measurement of the talonavicular coverage angle.

.jpg) Same lateral X-ray showing the measurement of Meary's angle, which is the angle between the long axis of the talus and first metatarsal bone.[16] This example is slightly convex downward. An angle greater than 4° convex upward is considered pes cavus.[16]

Same lateral X-ray showing the measurement of Meary's angle, which is the angle between the long axis of the talus and first metatarsal bone.[16] This example is slightly convex downward. An angle greater than 4° convex upward is considered pes cavus.[16] Foot with pes cavus (and os peroneum).

Foot with pes cavus (and os peroneum).

Types

The term pes cavus encompasses a broad spectrum of foot deformities. Three main types of pes cavus are regularly described in the literature: pes cavovarus, pes calcaneocavus, and ‘pure’ pes cavus. The three types of pes cavus can be distinguished by their aetiology, clinical signs and radiological appearance.[18][19]

Pes cavovarus, the most common type of pes cavus, is seen primarily in neuromuscular disorders such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and, in cases of unknown aetiology, is conventionally termed ‘idiopathic’.[20] Pes cavovarus presents with the calcaneus in varus, the first metatarsal plantarflexed, and a claw-toe deformity.[21] Radiological analysis of pes cavus in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease shows the forefoot is typically plantarflexed in relation to the rearfoot.[22]

In the pes calcaneocavus foot, which is seen primarily following paralysis of the triceps surae due to poliomyelitis, the calcaneus is dorsiflexed and the forefoot is plantarflexed.[23] Radiological analysis of pes calcaneocavus reveals a large talo-calcaneal angle.

In ‘pure’ pes cavus, the calcaneus is neither dorsiflexed nor in varus and is highly arched due to a plantarflexed position of the forefoot on the rearfoot.[24]

A combination of any or all of these elements can also be seen in a ‘combined’ type of pes cavus that may be further categorized as flexible or rigid.[25]

Despite various presentations and descriptions of pes cavus, not all incarnations are characterised by an abnormally high medial longitudinal arch, gait disturbances, and resultant foot pathology.

Treatment

Surgical treatment is only initiated if there is severe pain, as the available operations can be difficult. Otherwise, high arches may be handled with care and proper treatment.

Suggested conservative management of patients with painful pes cavus typically involves strategies to reduce and redistribute plantar pressure loading with the use of foot orthoses and specialised cushioned footwear.[26][27] Other non-surgical rehabilitation approaches include stretching and strengthening of tight and weak muscles, debridement of plantar callosities, osseous mobilization, massage, chiropractic manipulation of the foot and ankle, and strategies to improve balance.[28] There are also numerous surgical approaches described in the literature that are aimed at correcting the deformity and rebalancing the foot. Surgical procedures fall into three main groups:

- soft-tissue procedures (e.g. plantar fascia release, Achilles tendon lengthening, tendon transfer);

- osteotomy (e.g. metatarsal, midfoot or calcaneal);

- bone-stabilising procedures (e.g. triple arthrodesis).[29]

Epidemiology

There are few good estimates of prevalence for pes cavus in the general community. While pes cavus has been reported in between 2 and 29% of the adult population, there are several limitations of the prevalence data reported in these studies.[30] Population-based studies suggest the prevalence of the cavus foot is approximately 10%.[31]

History

The term pes cavus is Latin for "hollow foot" and is synonymous with the terms talipes cavus, cavoid foot, high-arched foot, and supinated foot type. Pes cavus is a multiplanar foot deformity characterised by an abnormally high medial longitudinal arch. Pes cavus commonly features a varus (inverted) hindfoot, a plantarflexed position of the first metatarsal, an adducted forefoot, and dorsal contracture of the toes. Despite numerous anecdotal reports and hypothetical descriptions, very little rigorous scientific data exist on the assessment or treatment of pes cavus.[32]

See also

- Arches of the foot

- Foot type

- En pointe

- Foot binding

- Rocker bottom foot

References

- Burns J. Landorf KB. Ryan MM. Crosbie J. Ouvrier RA. Interventions for the prevention and treatment of pes cavus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD006154. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006154.pub2

- Aktas S, Sussman MD. The radiological analysis of pes cavus deformity in Charcot Marie Tooth disease. J Pediatr Orthop 2000; 9: 137-40

- Barrie JL, McLoughlin C, Robem N, Nuttal R, Lishman J, Wardle F, Hopgood P. Ankle instability in pes cavus. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83-B: 339

- Korpelainen R, Orava S, Karpakka J, Siira P, Hulkko A. Risk factors for recurrent stress fractures in athletes. Am J Sports Med 2001; 29: 304-310

- Dahle LK, Mueller M, Delitto A, Diamond JE. Visual assessment of foot type and relationship of foot type to lower extremity injury. J Orthop Sports Phy Ther 1991; 14: 70-74

- Williams DS, 3rd, McClay IS, Hamill J. Arch structure and injury patterns in runners. Clin Biomech 2001a; 16: 341-7

- Builder MA, Marr SJ. Case history of a patient with low back pain and cavus feet. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1980; 70: 299-301

- Aktas S, Sussman MD. The radiological analysis of pes cavus deformity in Charcot Marie Tooth disease. J Pediatr Orthop 2000; 9: 137-40

- Burns J. Crosbie J. Hunt A. Ouvrier R. Novel Award: The effect of pes cavus on foot pain and plantar pressure. Clinical Biomechanics. 20(9):877-82, 2005.

- Burns J. Redmond A. Ouvrier R. Crosbie J. Quantification of muscle strength and imbalance in neurogenic pes cavus, compared to health controls, using hand-held dynamometry. Foot & Ankle International. 26(7):540-4, 2005.

- Brewerton D, Sandifer P, Sweetnam D. "Idiopathic" pes cavus: An investigation into its aetiology. BMJ 1963; 2: 659-661.

- Skre H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Clin Genet 1974; 6: 98-118

- Shy ME, Blake J, Krajewski K, Fuerst DR, Laura M, Hahn AF, Li J, Lewis RA, Reilly M. Reliability and validity of the CMT neuropathy score as a measure of disability. Neurology 2005; 64: 1209–1214

- Burns J. Redmond A. Ouvrier R. Crosbie J. Quantification of muscle strength and imbalance in neurogenic pes cavus, compared to health controls, using hand-held dynamometry. Foot & Ankle International. 26(7):540-4, 2005.

- Manoli A, Graham B. The subtle cavus foot, "the underpronator," a review. Foot Ankle Int 2005; 26: 256–63

- "Pes Cavus". University of Washington, Department of Radiology. Last modified: 2016/08/14

- Detailed explanations and references are located in the Calcaneal pitch article.

- Meehan PL. The cavus foot in: Morrisy, RT, (Eds), Lovell and Winter's Pediatric Orthopaedics, J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1990

- Aktas S, Sussman MD. The radiological analysis of pes cavus deformity in Charcot Marie Tooth disease. J Pediatr Orthop 2000; 9: 137-40

- Giannini S, Ceccarelli F, Benedetti MG, Faldini C, Grandi G. Surgical treatment of adult idiopathic cavus foot with plantar fasciotomy, naviculocuneiform arthrodesis, and cuboid osteotomy. A review of thirty-nine cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84-A: 62-9

- Meehan PL. The cavus foot in: Morrisy, RT, (Eds), Lovell and Winter's Pediatric Orthopaedics, J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1990

- Aktas S, Sussman MD. The radiological analysis of pes cavus deformity in Charcot Marie Tooth disease. J Pediatr Orthop 2000; 9: 137-40

- Meehan PL. The cavus foot in: Morrisy, RT, (Eds), Lovell and Winter's Pediatric Orthopaedics, J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1990

- Jahss MH. Evaluation of the cavus foot for orthopedic treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983; 181: 52-63

- Coleman SS, Chesnut WJ. A simple test for hindfoot flexibility in the cavovarus foot. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977; 123: 60-2

- Burns J. Crosbie J. Ouvrier R. Hunt A. Effective orthotic therapy for the painful cavus foot: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 96(3):205-11, 2006

- Wegener C. Burns J. Penkala S. Effect of neutral-cushioned running shoes on plantar pressure loading and comfort in athletes with cavus feet: A crossover randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 36(11):2139-2146, 2008

- Manoli A, Graham B. The subtle cavus foot, "the underpronator," a review. Foot Ankle Int 2005; 26: 256-63

- McCluskey WP, Lovell WW, Cummings RJ. The cavovarus foot deformity. Etiology and management. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; 247: 27–37

- Burns J. Landorf KB. Ryan MM. Crosbie J. Ouvrier RA. Interventions for the prevention and treatment of pes cavus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD006154. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006154.pub2

- Sachithanandam V, Joseph B. The influence of footwear on the prevalence of flat foot. A survey of 1846 skeletally mature persons. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77: 254-7

- Burns J. Landorf KB. Ryan MM. Crosbie J. Ouvrier RA. Interventions for the prevention and treatment of pes cavus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD006154. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006154.pub2.

External links

| Classification |

|

|---|---|

| External resources |