Foot drop

Foot drop is a gait abnormality in which the dropping of the forefoot happens due to weakness, irritation or damage to the common fibular nerve including the sciatic nerve, or paralysis of the muscles in the anterior portion of the lower leg. It is usually a symptom of a greater problem, not a disease in itself. Foot drop is characterized by inability or impaired ability to raise the toes or raise the foot from the ankle (dorsiflexion). Foot drop may be temporary or permanent, depending on the extent of muscle weakness or paralysis and it can occur in one or both feet. In walking, the raised leg is slightly bent at the knee to prevent the foot from dragging along the ground.

| Foot drop | |

|---|---|

| |

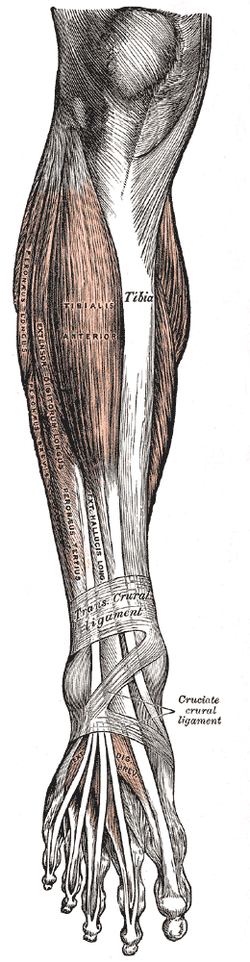

| Shown here, the right foot drops due to paralysis of the tibialis anterior muscle, while the left foot demonstrates normal lifting abilities. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Foot drop can be caused by nerve damage alone or by muscle or spinal cord trauma, abnormal anatomy, atoxins, or disease. Toxins include organophosphate compounds which have been used as pesticides and as chemical agents in warfare. The poison can lead to further damage to the body such as a neurodegenerative disorder called organophosphorus induced delayed polyneuropathy. This disorder causes loss of function of the motor and sensory neural pathways. In this case, foot drop could be the result of paralysis due to neurological dysfunction. Diseases that can cause foot drop include trauma to the posterolateral neck of fibula, stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, poliomyelitis, Charcot Marie Tooth disease, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, hereditary spastic paraplegia, Guillain–Barré syndrome, Welander distal myopathy, and Friedreich's ataxia. It may also occur as a result of hip replacement surgery or knee ligament reconstruction surgery.

Signs and symptoms

Foot drop is characterized by steppage gait.[1] While walking, people suffering the condition drag their toes along the ground or bend their knees to lift their foot higher than usual to avoid the dragging.[2] This serves to raise the foot high enough to prevent the toe from dragging and prevents the slapping.[3][4] To accommodate the toe drop, the patient may use a characteristic tiptoe walk on the opposite leg, raising the thigh excessively, as if walking upstairs, while letting the toe drop. Other gaits such as a wide outward leg swing (to avoid lifting the thigh excessively or to turn corners in the opposite direction of the affected limb) may also indicate foot drop.[5]

Patients with painful disorders of sensation (dysesthesia) of the soles of the feet may have a similar gait but do not have foot drop. Because of the extreme pain evoked by even the slightest pressure on the feet, the patient walks as if walking barefoot on hot sand.

Pathophysiology

The causes of foot drop, as for all causes of neurological lesions, should be approached using a localization-focused approach before etiologies are considered. Most of the time, foot drop is the result of neurological disorder; only rarely is the muscle diseased or nonfunctional. The source for the neurological impairment can be central (spinal cord or brain) or peripheral (nerves located connecting from the spinal cord to an end-site muscle or sensory receptor).

Foot drop is rarely the result of a pathology involving the muscles or bones that make up the lower leg. The anterior tibialis is the muscle that picks up the foot. Although the anterior tibialis plays a major role in dorsiflexion, it is assisted by the fibularis tertius, extensor digitorum longus and the extensor hallucis longus. If the drop foot is caused by neurological disorder all of these muscles could be affected because they are all innervated by the deep fibular (peroneal) nerve, which branches from the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve exits the lumbar plexus with its root arising from the fifth lumbar nerve space.

Occasionally, spasticity in the muscles opposite the anterior tibialis, the gastrocnemius and soleus, exists in the presence of foot drop, making the pathology much more complex than foot drop. Isolated foot drop is usually a flaccid condition. There are gradations of weakness that can be seen with foot drop, as follows according to MRC:

- 0 = complete paralysis,

- 1 = flicker of contraction,

- 2 = contraction with gravity eliminated alone,

- 3 = contraction against gravity alone,

- 4 = contraction against gravity and some resistance, and

- 5 = contraction against powerful resistance (normal power).

Foot drop is different from foot slap, which is the audible slapping of the foot to the floor with each step that occurs when the foot first hits the floor on each step, although they often are concurrent.

Treated systematically, possible lesion sites causing foot drop include (going from peripheral to central):

- Neuromuscular disease;

- Peroneal nerve (common, i.e., frequent) —chemical, mechanical, disease;

- Sciatic nerve—direct trauma, iatrogenic;

- Lumbosacral plexus;

- L5 nerve root (common, especially in association with pain in back radiating down leg);

- Cauda equina syndrome, which is cause by impingement of the nerve roots within the spinal canal distal to the end of the spinal cord;

- Spinal cord (rarely causes isolated foot drop) —poliomyelitis, tumor;

- Brain (uncommon, but often overlooked) —stroke, TIA, tumor;

- Genetic (as in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease and hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies);

- Nonorganic causes, e.g. as part of a functional neurological symptom disorder.

If the L5 nerve root is involved, the most common cause is a herniated disc. Other causes of foot drop are diabetes (due to generalized peripheral neuropathy), trauma, motor neuron disease (MND), adverse reaction to a drug or alcohol, and multiple sclerosis.

Gait cycle

Drop foot and foot drop are interchangeable terms that describe an abnormal neuromuscular disorder that affects the patient's ability to raise their foot at the ankle. Drop foot is further characterized by an inability to point the toes toward the body (dorsiflexion) or move the foot at the ankle inward or outward. Therefore, the normal gait cycle is affected by the drop foot syndrome.

The normal gait cycle is as follows:

- Swing phase (SW): The period of time when the foot is not in contact with the ground. In those cases where the foot never leaves the ground (foot drag), it can be defined as the phase when all portions of the foot are in forward motion.

- Initial contact (IC): The point in the gait cycle when the foot initially makes contact with the ground; this represents the beginning of the stance phase. It is suggested that heel strike not be a term used in clinical gait analysis as in many circumstances initial contact is not made with the heel. Suggestion: Should use foot strike.

- Terminal contact (TC): The point in the gait cycle when the foot leaves the ground: this represents the end of the stance phase or beginning of the swing phase. Also referred to as foot off. Toe-off should not be used in situations where the toe is not the last part of the foot to leave the ground.

The drop foot gait cycle requires more exaggerated phases.

- Drop foot SW: If the foot in motion happens to be the affected foot, there will be greater flexion at the knee to accommodate the inability to dorsiflex. This increase in knee flexion will cause a stair-climbing movement.

- Drop foot IC: Initial contact of the foot that is in motion will not have normal heel-toe foot strike. Instead, the foot may either slap the ground or the entire foot may be planted on the ground all at once.

- Drop foot TC: Terminal contact that is observed in patients that have drop foot is quite different. Since patients tend to have weakness in the affected foot, they may not have the ability to support their body weight. Often, a walker or cane will be used to assist in this aspect.

Drop Foot is the inability to dorsiflex, evert, or invert the foot. So when looking at the Gait cycle, the part of the gait cycle that involves most dorsiflexion action would be Heel Contact of the foot at 10% of Gait Cycle, and the entire swing phase, or 60-100% of the Gait Cycle. This is also known as Gait Abnormalities.

Diagnosis

Initial diagnosis often is made during routine physical examination. Such diagnosis can be confirmed by a medical professional such as a physiatrist, neurologist, orthopedic surgeon or neurosurgeon. A person with foot drop will have difficulty walking on his or her heels because he will be unable to lift the front of the foot (balls and toes) off the ground. Therefore, a simple test of asking the patient to dorsiflex may determine diagnosis of the problem. This is measured on a 0-5 scale that observes mobility. The lowest point, 0, will determine complete paralysis and the highest point, 5, will determine complete mobility.

There are other tests that may help determine the underlying etiology for this diagnosis. Such tests may include MRI, MRN, or EMG to assess the surrounding areas of damaged nerves and the damaged nerves themselves, respectively. The nerve that communicates to the muscles that lift the foot is the peroneal nerve. This nerve innervates the anterior muscles of the leg that are used during dorsi flexion of the ankle. The muscles that are used in plantar flexion are innervated by the tibial nerve and often develop tightness in the presence of foot drop. The muscles that keep the ankle from supination (as from an ankle sprain) are also innervated by the peroneal nerve, and it is not uncommon to find weakness in this area as well. Paraesthesia in the lower leg, particularly on the top of the foot and ankle, also can accompany foot drop, although it is not in all instances.

A common yoga kneeling exercise, the Varjrasana has, under the name "yoga foot drop," been linked to foot drop.[6][7]

Treatment

The underlying disorder must be treated. For example, if a spinal disc herniation in the low back is impinging on the nerve that goes to the leg and causing symptoms of foot drop, then the herniated disc should be treated. If the foot drop is the result of a peripheral nerve injury, a window for recovery of 18 months to 2 years is often advised. If it is apparent that no recovery of nerve function takes place, surgical intervention to repair or graft the nerve can be considered, although results from this type of intervention are mixed.

Non-surgical treatments for spinal stenosis include a suitable exercise program developed by a physical therapist, activity modification (avoiding activities that cause advanced symptoms of spinal stenosis), epidural injections, and anti-inflammatory medications like ibuprofen or aspirin. If necessary, a decompression surgery that is minimally destructive of normal structures may be used to treat spinal stenosis.

Non-surgical treatments for this condition are very similar to the non-surgical methods described above for spinal stenosis. Spinal fusion surgery may be required to treat this condition, with many patients improving their function and experiencing less pain.

Nearly half of all vertebral fractures occur without any significant back pain. If pain medication, progressive activity, or a brace or support does not help with the fracture, two minimally invasive procedures - vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty - may be options.

Ankles can be stabilized by lightweight orthoses, available in molded plastics as well as softer materials that use elastic properties to prevent foot drop. Additionally, shoes can be fitted with traditional spring-loaded braces to prevent foot drop while walking. Regular exercise is usually prescribed.

Functional electrical stimulation (FES) is a technique that uses electrical currents to activate nerves innervating extremities affected by paralysis resulting from spinal cord injury (SCI), head injury, stroke and other neurological disorders. FES is primarily used to restore function in people with disabilities. It is sometimes referred to as Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) The latest treatments include stimulation of the peroneal nerve, which lifts the foot when you step. Many stroke and multiple sclerosis patients with foot drop have had success with it. Often, individuals with foot drop prefer to use a compensatory technique like steppage gait or hip hiking as opposed to a brace or splint.

Treatment for some can be as easy as an underside "L" shaped foot-up ankle support (ankle-foot orthoses). Another method uses a cuff placed around the patient's ankle, and a topside spring and hook installed under the shoelaces. The hook connects to the ankle cuff and lifts the shoe up when the patient walks.

See also

- Yoga foot drop

- Toe walking

- Polymyositis

- inclusion body myositis

References

- "Definition of Steppage gait". MedicineNet, Inc. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "Walking abnormalities". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "high stepping gait". GPnotebook. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Mayo Clinic staff. "Foot drop". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- http://www.painontopoffoottalk.com Archived 2014-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Joseph Chusid (August 9, 1971). "Yoga Foot Drop". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 271 (6): 827–828. doi:10.1001/jama.1971.03190060065025.

- William J. Broad (January 5, 2012). "How Yoga Can Wreck Your Body". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2011). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

- Balali-Mood, Mahdi (January 2008). "Neurotoxic disorders of organophosphorus compounds and their managements". Arch Iran Med. 11(1):65–89. PMID 18154426.

- Jokanovic, Milan, Melita Kosanovic, Dejan Brkic, and Predrag Vukomanovic (2011). "Organophosphate Induced Delayed Polyneuropathy in Man: An Overview". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 113.1: 7–10. PMID 20880629. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.08.015.

- Mayo Clinic. "Foot Drop".

- Pritchett, James W., MD (June 21, 2018). "Foot Drop". Vinod K Panchbhavi, MD, FACS (ed.).

- Saladin, Kenneth (2015). Anatomy & Physiology: A Unity of Form & Function. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. Print.